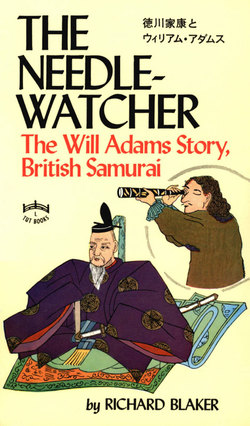

Читать книгу Needle-Watcher - Richard Blaker - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER XIII

MITSU explained to Adams and Santvoort that the houses to entertain them were but a stone's throw from each other. Santvoort's was the first they came to, about a mile from the jetty; and the Dutchman went cheerfully in with the bundle he had brought from the ship, saying he would visit Adams when he had made himself comfortable. "In the morning, Hollander," Mitsu said. "It is already late, and men may not be abroad by night so near to the palace, unless a soldier accompany them."

"Very well, morning then," Santvoort agreed.

For nearly two and a half years now Adams and Santvoort had scarcely been out of earshot of each other. If this sudden parting of them gave any hint of purpose sinister, the suggestion was denied by the easy, cheery manner of Mitsu. He motioned and spoke to a youth who had stood in the road, idly watching them, and the youth at once came forward and took from Adams the bundle he had made aboard in a piece of sailcloth.

"Your host, An-jin, is a man of some distinction," Mitsu explained as they strolled on. "A soldier. It would embarrass him to see his guest carrying his own luggage."

"And the boy?" Adams asked, indicating the porter.

"Oh—he? One of the City's young." It was as though Adams had asked him the name of some particular pebble in a watercourse, of a grain in a dish of rice. "They fetch and carry. They ply trades of one sort or another."

"And do the bidding of any man who commands them?" asked Adams. "Are they slaves then? Dogs?"

"Slaves?" said Mitsu in surprise. "Certainly they are not slaves and dogs. But I am a soldier."

"And my host also is one who may go out and command men to do things?" Adams asked.

"Certainly," said Mitsu. "If he has justice and reason. It is just and reasonable that a loitering youth should carry dunnage for a soldier or his friend and guest."

"How long, Mitsu, is this to go on?" Adams asked. "I mean this 'guest' business?"

"That," said the other, "is between you and the General."

"But I have work to attend to," Adams said. "We came here for a purpose and can still fulfil it with our cargo."

"As to work, it may be that the General will himself have work for you to do, apart from the cargo. But you will be very well in the house of Magome Sageyu, your host."

"And suppose I will not do the Emperor's work?" asked Adams.

"Then," said the other, shrugging his shoulders, :'I suppose you will not do it. It is no great matter. To-morrow, however, I will come to take you to the palace where the General would speak with you."

The door of the house was opened by Magome Sageyu himself. In the brief moment of ceremonial of meeting and greeting, the youth with the bundle was utterly ignored. He put down the bundle on the doorstep and loitered off. Magome clapped his plump hands together and a girl appeared in the narrow hall-way. Magome, without interrupting his speech with Mitsu, indicated the bundle. The girl passed by the three men, a glint of ebony teeth between her smiling lips. She stooped to the bundle, turned with it, and was gone again into the back of the house. Magome chatted on, his hands resting each on a sword hilt, and Mitsu translated his welcome and the extension of the meagre and rough hospitality of a simple old soldier and his daughters to the distinguished Contemplator of the Needle.

Adams felt rather a fool. "Contemplator of the Needle," set him awkwardly on stilts of some sort. The peculiar, faint bombast that had come into the manner of Mitsu as he stood up to Magome and his phrases, sword-hilts to sword-hilts, while Adams stood with his hands in the empty pockets of the breeches he had donned for the occasion, was foolery. Yet a warmth came from the geniality of the little old soldier with a wrinkled forehead that shone from his eyebrows to the top of his head, darkened only by a long scar, and the mouth that flickered with glib phrases and set again into a toothless smile. This warmth was not foolery; nor was the smile of the little creature—child or woman—whose back, nimbly bent for the picking up of Adams' dunnage, had been a smooth sash and enormous bow; nor was foolery the passing friendliness that had met him in the eyes that glanced up from a dozen or fifteen inches below the level of his own.

He had pushed off his sandals, as Mitsu had discarded his. They followed their host through the small hall and the room at the end of it, to the steaming bath-tub. Already there was a change of clothes there for Adams out of his bundle, native drawers and shirt and tunic and coat.

Adams fussed for a few moments after the bath, over the clothes he had discarded, but Mitsu told him it was no matter, the women would see to them.

Wine and the meal were served by the girl who had carried off the bundle and another almost indistinguishable from her.

There was no harshness in the way old Magome ignored his two daughters. His benevolence seemed to be for their ministrations and to include the girls merely as a part thereof.

The click and rattle of speech that Adams heard was beginning at last to be not mere gibberish. His ear was beginning to detect words and phrases and sentences; questions and answers; sagacities and jests—they were still meaningless, but they had some hint of shape. The friendliness between the two soldiers when the wine had warmed them and the food comforted them out of their first ceremonious stiffness, the inclusion in it of the dumb needle-watcher squatting on his heels, and his inclusion equally in the silent, deft service from the girls gave him an ease which he had seldom known before. For where had there ever been such a general smoothness? Certainly not during the apprenticeship in the shipyard of Nicholas Diggins in Limehouse. Not on the barges and hoys of the coastal trade, nor the nondescript victualling-ships of Elizabeth's Navy; not in the handier vessels of the Barbary Merchants where he had learned his craft of needle-gazing and star-reading.

In the little brick house on the hill at Gillingham he might, perhaps, have known glimpses of such ease; but there, in Gillingham, there had always been an end to them. Mary, the thrifty one, knew only too well that there was a bottom to every purse of a seaman's wages; and in those hard days Mary knew, and Adams knew, that every meal in the house at Gillingham drew the bottom of the purse nearer to the top. In the course of jobs grabbed up because they were better than nothing with intervals of waiting and scrambling for them, Mary became the double responsibility of Mary and a child; then another child; and spaciousness and ease were altogether gone from Gillingham. They had been gone from a dozen years of restless life.

In the eating of that first dinner in the house of Magome Sageyu an opinion was formed in the mind of Will Adams. A dozen years later he committed it thoughtfully to a sheet of rice paper with a reed pen: "the people of this island of Japon are good of nature, courteous above measure . . ."

Ceremonial stiffness came again, from nowhere, into the bearing of the host and Mitsu when Mitsu rose to go. A lantern was brought for him by one of the daughters, since no man might be abroad by night without advertising himself for any to see, by a light. Another call from Magome—some words including the familiar "An-jin" produced another lantern from the back of the hall, in the same hands that had carried away the pilot's bundle.

Adams followed Magome and the girl with the lantern to a little room at the end of the passage. A sleeping-mat was spread for him, and a coverlet. Smiling some gently silent message of goodness of nature, of courtesy above measure, the girl slid aside a papered panel of the room's side and showed the small cupboard where the contents of Adams's bundle had been set out—his breeches and his already washed and dried shirt, his instruments and two books, his woollen cap, a horn spoon and some English pence.

Adams could say "Thank you"; and he said it slowly, twice. The girl withdrew, and her father smilingly begged that the needle-contemplator would deign to sleep in peace and honourable comfort in a place so poor. Adams recognised the good-night phrase and answered with "Sleeping honourably." To Magome, too—excited a little towards a chuckle by the pilot's speech—Adams said "Thank you."