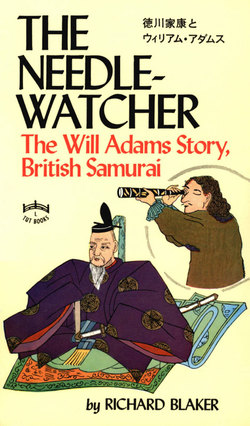

Читать книгу Needle-Watcher - Richard Blaker - Страница 29

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER XX

THIS fact remained clear in his mind the next morning from the general tumble of the night's ideas, clear and solid as Magome's receipt and the folded pantaloons that were added to his possessions.

He advanced towards his fog-watching on his first encounter with Magome. He confronted him with the writing-brush and ink and a paper napkin and tried to make it clear that he wanted to learn to write his name of Needle-watcher, An-jin. The old man shuffled so that Adams thought his meaning was missed. "Magome, then," he said, "Magome Sageyu." He would have explained himself by producing the receipt with the signature, but Magome readily took the brush. He scorned the napkin, however, and produced a small sheet of paper from the writing box, after economically passing over several slightly larger ones. Good paper, Adams perceived, was not to be trifled with to the extent of using a large piece when a small one would do.

Magome wrote his name and Adams tried him again with An-jin; but the old man, admitting no defeat, called Bikuni. She wrote the signs, or drew the pictures that were the signature of Adams—and it was clear that hers was fine writing while her father's was a scrawl. She wrote her own name for Adams next, and then the name of Magdalena.

But it was many days before the fog began to lift.

He had enough Dutch for fluent conversation with Santvoort; enough Portuguese for a rough understanding, and a little Spanish. These he had acquired from the simple fact that the human ear is permanently open. He had taken no particular steps about the matter. Words had tumbled into his ears and fixed themselves in his brain to fit themselves to a skeleton of idiom and of thought that was the same for all of them.

But the Japanese language was no language at all. Xavier, studying it with the devotion of a scholar and the patience of a saint, gave it as his balanced opinion that the tongue of Japan was Satan's masterpiece of a device for keeping a people in ignorance of the works and the mercy of God. It served, at any rate, to keep the bewildered Adams in ignorance of the thoughts of Magome, the old pensioned soldier, and the thoughts of Bikuni, his daughter.

Magome saw in the Pilot a chance such as he had never seen before; and Bikuni, in the most accurate sense of ballad and romance, was in love with him.

Magome was, first and last and all the time, the phenomenon unique in a unique society for which "gentleman" was a weak and colourless word. An Englishman of leisure appeared in due course in Japan. A man of even his resources in the matter of accurate terms and words nicely chosen (if spelt slap-dash) was stumped by the phenomenon of such as Magome. The word he found for them at last was Cavalero.

Some forty years before the arrival of Adams at the house of Magome, an argument in the street of a Southern village had produced a headless trunk in the gutter, the wound upon the head of Magome and—just as the blood from it was blinding him and his senses were tottering—a second corpse, the younger brother of the first one.

It was then, by the luck of good soldiers, the hour of dusk.

A servant carried Magome to a boat; for he who had killed, except an enemy of his Lord in battle, must either cut his belly or fly.

The times, on the whole, were easy ones for a swordsman of any repute. Gentlemen, such as Magome, exiled by an immutable law from their own province, became "Ronin." They were the focus, if they were worth it, of a vow of vengeance; but they found employment enough and a soldier's ration in practically any province that appealed to them, so long as their swords remained good.

Only twice in the course of the forty years had Magome been constrained to move on again from his adopted provinces— when the vendetta (duly and officially registered with the Notary) had developed as far as the crises which Magome faced with his usual skill. It was now twenty-six years since there had been any crisis or any menace; and the vendetta was probably forgotten. If any members had survived of the families of the two brothers whose insulting behaviour and poor swordsmanship had made of Magome a Ronin, and of the families of the two avengers who had subsequently joined them, they had probably become hucksters of one sort or another in the Southern and Western towns. For it was there that doubloons and rialls of eight were becoming weapons that blunted the edges and corrupted the metal of the swords of the Samurai. They had probably forgotten, these kinsmen of the dead four; they had forgotten Bushido, the code of the Samurai, and become men of business, chaffering with Portuguese and Spanish pedlars and their half-bred and polyglot rabble that was said now to overrun the village of Magome's youth.

The old man still spat when he thought of it—of a soldier who would trade, and forfeit the status of soldiers.

But even a soldier had to live; and Magome was becoming old for soldiering. He had, furthermore, his daughters. To live—and that they should live in seemly style—he had swallowed pride as much as it was fitting that any cavalero of the old school should swallow it. leyasu in his fortress-city of Yedo, through his underlings, had given casual work to Magome as he gave it to any cavalero of the old school—a man who kept his given word as certainly as he used his drawn sword; but the ageing man's gorge rose against the indirect service of a Lord through the agency of underlings as it rose, more and pitiably more, against hard rations and bare lodging where other men, younger and less tried, could daily be seen lording it.

It was lawful and seemly that a swordsman should receive a fee for teaching his craft to the young, provided that they, too, were of the right blood. For twenty-five years he had taught fencing in the yard of his house and thus been able to buy, honourably, a measure of wine for occasions.

What he wanted, however, as his years increased, was an estate. The small one to which he had been bora had gone from him, by immutable law, when the head had gone from the shoulders of the bragging and jeering young man who had drawn his sword against him; and the miserable fees of a fencing master were not likely to produce an estate to replace it. The work he did unwinkingly in the secret service of the Shogun was the simple routine duty of a soldier and its fee was no more than his house and rations.

At other times, perhaps some stripling pupil would have cast his eyes upon the master's daughters, or would have been approachable through a marriage-agent—if Magome could have raised the agent's fee; but now—and for the past half-dozen years—noble families had been imported yearly into Yedo as hostages, and there were dowered brides and to spare for any young man whom Magome would have considered decent—a man, that is, who served not underlings of the Shogun but the Shogun himself.

Mitsu, straight from the Shogun, billeting Adams upon the old man, had said "Treat him handsomely. He is a worthy one and approved by the General." He had produced coins to ensure entertainment that befitted a worthy one, approved by the General; and Magome had thought at first, with some hardness and bitterness in his heart, that here would be another underling to lord it over himself.

When he saw that Adams was no dignitary, but a simple, sprawling creature who squatted with a kite-maker and played with the tools and the chips of wood in the yard of a carpenter, he saw that the wind is ill indeed that blows no good. Vaguely, too, he liked the Pilot. When he saw him push his prodigious hairy right hand into his sash instead of using it to firm the document leasing the Liefde's guns to the Shogun, he was struck into a state of most acute attentiveness. When he read the figures in the document itself his attentiveness reached a pitch of bewilderment.

On the basis of those figures he had spent a day estimating the Pilot's share of the money at about twenty tael; and the Pilot had lounged in, as though nothing whatever had happened, with forty-three. From rousing the old man's imagination, he had proceeded, still as though nothing had happened, to touch his heart. He had done it with his smile, perhaps; or with the magnificence of five tael held out in his great paw to the threadbare cavalero, and with his simple confidence in handing over to his care all he possessed in the world.

It is small wonder, then, that the cavalero ripped away from the loins of the Needle-watcher the close-fitting linen that was emblematic of meniality, and gave him first the nudity and then the voluminous hakama of the gentleman-at-large.

And Bikuni, whose very humility would have made her speechless if she had not been already dumb to the Pilot, was utterly in love with him.

Magome had been a widower for a dozen years. When he had settled in Yedo after the two old encounters that had seemed to see the end of the vendetta, his wife had joined him. She was an old woman nearing forty when she set out from her brother's house to join the husband she had not seen for twenty years. A son was beyond her; but she bore Bikuni and Magdalena with the least possible delay.

She had done towards their education whatever could be done for genteel children by the time one of them was ten and the other seven. When she died her piety and devotion to the fencing-master with the cleft crown were already a distinguished example of conduct, and a tale that was told to the young. The children of such a mother, and of a father with sword-play that was also a tale told to the young, were companions welcome in the household of any hostage-nobleman.

They thus grew up, with the thoughts and in the practice of the craft of ladyship. They could write so that the elegance of their writing was the envy of greater calligraphists than Magome who had summoned Bikuni to set down the pictures of three or four names. They could answer verse with verse and they could meditate upon fortitude and fidelity and obedience, and other virtues that were of the mystery of love. On the lure of it they could also meditate; upon its warmth and its depth and its sweetness.

It was unseemly (in the writings of the sage) that young women should occupy themselves with the wearing apparel of men-folk in the household; but in a household where there was no matron and where a man was as helpless as the Needle-watcher, seemly conduct itself demanded that Bikuni should execute the duties of matron.

It was she, therefore, who sewed and unpicked and washed and sewed again the garments of Adams; thinking, as she folded them, of the great chest they would enfold, of the broad back, white and peculiarly smooth, while the chest was rough with hair, of the arms that were prodigious in their girth, but shapely.