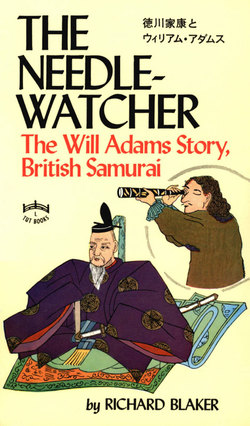

Читать книгу Needle-Watcher - Richard Blaker - Страница 24

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER XV

To Santvoort he said, "We might as well face it, Melchior. Here we are, and here we are likely to stay. He will not let us go, and go we cannot."

"What is it he would do with us?" asked the Dutchman. Adams treated the question as though it had been addressed to Mitsu, who was walking back with them. But since Mitsu treated it as though he himself had been a dozen leagues away, Adams said, "God knows . . . make gunners of us, perhaps—but look—" he pointed at an immense bronze piece mounted at an embrasure in the wall. "Mitsu," he said; "you have ordnance already."

"Yes," said Mitsu, "in abundance. But it is said that pieces from your Europe do not, at times, split in the firing."

"Have you gunners then?" asked Adams.

"Yes," said Mitsu. "Not soldiers, you understand—but artisans from below; makers of crackers and fireworks. They shoot off ordnance when there is need, for a wage. It is not, I think, for the base occupation of working cannons that the General would hold you as his—"

"For God's sake," Santvoort interrupted him, "don't say 'guests' again. It is the best joke we have heard in this country, but it was the first one and it has lost its fun."

Adams was thinking that it was, at any rate, time now for Mary to have lodged her claim in Rotterdam and to have had justice and payment from that good uncle of Santvoort's.

"What is your Japan word for 'guest,' Mitsu?" he asked.

Mitsu very solemnly said, "Okyaku Sama."

Adams repeated it. Then to Santvoort he said, "Swallow that, Melchior. And look——"

They stopped, looking towards the harbour.

Mitsu said, "You see your road now and I will return to the castle. If you lose your way any man but a zany can put you upon it again. I will see you again to-morrow, An-jin, when you have told your captain of his loan to my General. You know the house of his lodging, by the water. If you have need of anything, tell Magome."

"Aye," said Adams, "I'll tell him. I know your language now. 'Okyaku Sama'—honourable guest."

"It is sufficient for the time being," said Mitsu and left them.

They stood still, looking at the harbour.

The sun was at its height and their two shadows were the shadows of their great straw hats; discs that touched, rim to rim, in the soft white dust of the road. Behind them was the castle that Ieyasu had built as a bulwark against the Eastern turbulence in his early days, and now was his bulwark against the treachery of West and South. Its strength was of stone and mortar, of bronze pieces and of powder and shot. The cement of this bulwark was the mortar that held the stones together; it was also the judgment of Ieyasu that picked his men, and the peculiar genius of him that held them. The palace was the symbol, in the sprawl of city, of the city's unity. And the city's unity was the unity of a storm. There were currents in it, and under-currents, and whirls and eddies; there were depths and shallows, raging wildnesses and stillnesses as of death. Stillnesses that were death. The men of it had thoughts that mingled together into the single thought of an army; and thoughts that were solitary, incommunicable by word, but active in every daily shift of each man's matching his poor wits against a hard destiny. Every neighbour, every stranger, every friend was a tool for the hazardous cobbling together of a livelihood, for the fabrication of a scheme, the materialisation of an ideal whose material was nought but the conduct of men.

And it was heedless of this storm and its whirls and eddies that the two strangers stood in the shadow of their straw hats looking over the squat roofs of the crazy city of Yedo that was to become Tokyo.

They raised their eyes to the sky and stood without moving; for they beheld above the roofs a dragon. It was scarlet in the light and black in the creases of its shadows; and it lurched and swooped away from a colossal fish.

The monsters circled and manœuvred while the Englishman and the Dutchman watched them in wonder.

They stood poised in the air. They trembled and shook as they sped abreast, further aloft from the earth, till the dragon suddenly stopped and tottered. It writhed in an agony and then tumbled away, sinking slowly and lifeless to earth again, like a corpse trembling on the tide.

The fish soared magnificently upward. . . .

"God!" said Adams. "They can make kites that will answer the helm of a thumbnail at their thread's end a mile away. . . . And they rig their ships square with shutters of wood instead of sails, and with as much answer in them to wind and helm as a gammon of ham."

"They've made us answer to wind and helm right enough," said the Dutchman. Then he shrugged his shoulders. "I'm sorry, Will, for you, with your wife and your home and such like. For me it does not matter. He can't keep us here for ever; and I'd as lief see something of this land. It's been a great way to come, and——"

"Aye," said Adams thoughtfully. "He can't keep us here for ever. I, too, would as soon—as soon——" he glanced, as he hesitated, over roofs and dusty roadways, at the harbour with its rabble of junks and skiffs and rafts of timber. "I'd as soon— I mean, Melchior—if we went home now, we would be going as a failed and tatterdemalion lot; empty-pouched and empty-handed. But when we do go——"

That was all they could say of it; so they walked on.

"The captain will take it in pepper," said Santvoort.

Adams said, "Not he. He's too weary for sneezing. I'll tell him it is good that we stay awhile and fill our pockets; and as good he will take it."

Adams was right. The captain was older than himself by ten or a dozen years, older than Santvoort by twenty-five. His life, ashore and afloat, had been a series of small, successful commands; for a shipmaster was a commander first and a sailor second, since the mere technicalities of sailing were a job for the pilot. Ashore he had commanded details of the coastal garrisons; afloat he had commanded units of a flotilla. His schooling, therefore, was less in the invention of orders than in the taking of them, and handing them on.

Adams and Santvoort found him seated with the surgeon in the courtyard of their house. It was a larger house than Magome's, brighter in the painting of its pillars and, unlike the kite-maker's that lodged Santvoort, neat and uncluttered in the courtyard.

The two Dutchmen, still snobbish with their buckled breeches and cloaks, their woollen hose and leather shoes, sat on a low bench—strange giants where the oaks and pines of the garden's edge raised their gnarled and ancient shapes no higher than the stranger's heads.

Beyond the garden there was a bright knot of men and women and a scramble of children, smiling and chattering and staring.

Adams and Santvoort saluted, and the antic produced a rattle of comment from the onlookers; the word "An-jin" clicked freely in the talk.

"The Emperor sent for me, Captain," Adams said, wasting no time. "We are to stay here a while. A year perhaps." This last statement was no conscious invention. A year, or a little more or a little less, had occurred in his mind as the reasonable period wherein a naked man might clothe himself, might fill his pockets and find some means of returning to the wife and country that claimed him.

The information did not particularly disturb the captain. It was, in fine, an order.

"There is some business done," Adams went on. "His Majesty would place some of our pieces on his walls. They are skilled in the use of ordnance and already have some good pieces of their own casting. Ours will be as well on the walls as in the ship. Besides, Captain, when we get leave to unlade the ship, and trim her, the ordnance will be well out of her. You are to fix a fee for its hire."

The captain thought a few moments. It was scarcely his affair, this business in its details. He supposed, however, that as he was now Admiral, he could not utterly wash his hands of it.

"That is good," he said. "See to it, Mr. Adams, and tell me. See also to the cargo, you and Santvoort, and make a full inventory. And the crew must be held in hand, Mr. Adams. Find their lodging from your interpreter so that, if there be occasion, there can be a muster."

He had had many a company in billets before this. He knew the difficulties, but his very familiarity with them made of the difficulty a vague comfort. "If the lodgings are scattered they must be changed so that word may pass easily from one to another."

Adams did not argue the point. He was well satisfied, for the moment, with the captain's acceptance of the position, and with the surgeon's silence. Any questioning from them would have aggravated the questions at the back of his own mind, questions which he could only answer by dealing with destiny as it was, and not as it was not but might be.