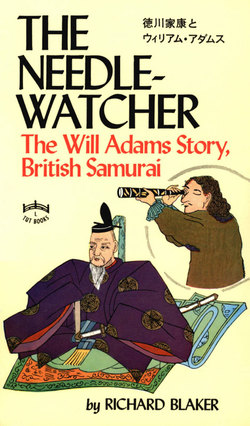

Читать книгу Needle-Watcher - Richard Blaker - Страница 27

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER XVIII

MAGOME was pompous no more, nor huffy with his guest the Pilot.

Adams could squat with Santvoort beside the kite-maker or his neighbour, a carpenter, and amuse himself with tools on scrapped pieces of wood, and the old soldier, bristling with his swords, would pause with a hand resting on each hilt and speak to the artisans and again, more cheerily and more slowly, to the Pilot and the Dutchman.

The Liefde's guns had been removed and a bag of money paid over to Adams and the Captain. Mitsu had explained the coins; explaining, with a Spanish riall of eight, that a tael was its equivalent; that ten mace were a tael, ten candereen a mace, and a hundred gin a candereen.

In the course of the explanation it became clear, with no allusion to such a triviality, that any man who conveyed money from one man or one place to another received, as by a law of nature, some of the money he had so conveyed. In obedience to this august law—surprised by it, but awed by its majesty into acceptance—Mitsu smilingly tied three tael into the corner of his tunic and went his way.

The captain, the surgeon, Adams and Santvoort set out the balance on the bench in the garden of the lodging and counted it. The amount was duly set down by the Captain in his book, with a brush and ink-block borrowed from the merchant in the house; its value in rialls of eight and in Dutch crowns was duly set against it. It was agreed among the four, and their argument formally recorded in the book, that money was due to them and to the crew, and that this money was distributed among them against such due in proportion that tallied with the proportions of their wages from the Company. The captain, now Grand-Admiral of the fleet, pushed aside his share into a separate heap. Adams, Pilot-major, took his. The surgeon, as Surgeon-General, and Santvoort, boatswain-in-chief, took theirs. The balance was divided into twelve equal piles.

Adams and Santvoort went forth to muster the crew, proclaiming to them the distribution of a prize; and the crew was not long in answering the summons. They turned up, all twelve of them, from the street that lodged them, followed by every available member of their respective households. The Swart waved back the three girls that were his especial escort and they fell into the crowd that stood happily in the road while the captain addressed his men.

He was the good commander again and they listened attentively to him. Those that wore breeches hitched them about their waists and hooked their thumbs into belts. Those that wore drawers and tunics and jackets pulled them and straightened them and stood with folded arms.

They were twelve, the captain pointed out, instead of fourteen because two, being blackguards and rascals, had gone the way of blackguards and rascals—God knew where. From that they could see for themselves that straight behaviour was expected of them and demanded of them. The money he was about to hand to them was on account of wages. He would endeavour, when the time came, to show the Company the fairness of considering it as prize, in addition to wages, but he wanted it to be clear that decision on this point rested, not with him, but with their employers. They must continue to bear their employers in mind. It was only for a short time, as seamen for a little while ashore, that they were scattered thus, and idle. Their indentures still held. Chance, just as it had landed them there, would set them aboard again; for the Emperor was a fair and just man. He urged them to comport themselves peaceably and well, a credit to himself and to their country; for they could best serve their country among these strange people by showing that its men were sound, peaceable and decent. He alluded to the vicissitudes that could well arise from over-whoring, from squandering their prize on debauchery and brawling.

He made each man, as he took his money, put his mark against his name in the book.

The sail-maker, supported by the Swart, raised a cheer. The Swart's three girls were close about him again, clamouring and scrambling and laughing up to his broad white grin. The twelve were immersed breast-deep in the gay tide of their friends; and the tide bore them back again to the bazaar.

The captain and the surgeon had breeches pockets in which to stow their treasure; Adams and Santvoort, in their tight-fitting artisans' drawers draped over with tunics and short summer-robes, adopted Mitsu's simple way of tying the great coins into the corners of their garments. They walked slowly and thoughtfully, holding up the robes to keep the weighted ends from knocking against their shins.

"What are you going to do with it, Will?" Santvoort asked.

"Change one of the smaller pieces and go out to discover something of the worth of it," said Adams. "The rest I shall give to the old man, my host, to keep for me."

"And when he has kept it for you?" asked the Dutchman. "What then?"

"Who can say 'What then?'" Adams answered testily, for it seemed that Santvoort was trying to bait him. "A man need not spend all the money he gets as soon as he gets it. Unless he is a fool."

"Or a cleverer one than we are, Will." Santvoort was serious enough. "It could as well be a bunch of stones for all the good it can do us—and so I am better off than you in having the smaller load to carry. For what is money to men who have food and drink set before them whenever they sit down in a house? Food that is only a bag of wind, it is true, with no ballast; and drink in morsels that warms the belly but leaves the head cold. Still, it's the best they can do; and money could not improve upon it."

"We don't know that, Melchior," said Adams; "when we can speak the language we might find—something."

"Women?" suggested Santvoort. "Nay, there are women in abundance even for the dumb. In my house there are too many. It has but five rooms or three—according to whether they hoist or furl the walls between them. . . . My house is not like yours, Will."

"No. Mine is no bawdy-house," said Adams. "And it were perhaps as well for you to remember the same. That old man, by all accounts, is no loiterer in the matter of drawing his swords; and if those girls are not his daughters, they are his wives. But I think they are his daughters."

"Praise God on their behalf, that it is not from any family likeness that you say that!" the Dutchman chuckled. Then he became thoughtful again. "Will," he said, "the eye becomes adjusted to strange things. If I were to see now what we once would have called a fine girl I think I would laugh, as Mitsu and the others always laugh when they call us 'old hairy ones.' These women here with their black teeth and oiled top-knots, creatures so small as to run two to a good armful—they stay in my mind, even when my eyes are shut, as great possibilities of loveliness."

Adams smiled. He had heard expositions enough before from the Dutchman on the subject of women; but he had never known them take a wistful turn.

"Perhaps," he suggested, "you could buy a house with that money of yours. Your host has paper enough to make you one."

Santvoort ignored the joke. He said, "It is difficult to recollect what we did spend money on—except women."

"You might have spent it on nought but women," said Adams. "I—"

"Pah!" Santvoort interrupted him. "You even more than I. I only hired them while you spent all you had—and all you were likely to have—on paying for the one you had got. So it is all the same. When your belly is full and there is a shirt to your back, the only use for money is women. Not a dozen women filling a house like mine to overflowing. But one——"

"For you, Melchior?" Adams laughed. "One woman? Say one at a time, lad."

Santvoort was puzzled by the Englishman. At times he would be solemn as an owl over nothing, as huffy and as testy as an old great uncle; and at others he would break out in cheery ribaldry.

"One at a time, then," he admitted sulkily. "For that is all that even you can say. And you've had your own already— for eight years or ten, before we sailed, you'd had your house and your wife—so it would not matter if you were now shut in a paper house with a dozen women all as beautiful—when your eye has once got adjusted to them—as a flower or butterflies. You could sleep on a bag of money and dream richly. But you, who do not deserve it—"

"Make no mistake, Melchior," Adams said quietly. "There is no frolicking with the women in my house." He said it only out of kindness. Melchior, for all his austere and able handling of any rabble aboard a ship, had fallen into many a silly scrape ashore. It could well have escaped whatever machinery of perception functioned in his square skull that Magdalena and Bikuni San were a different story altogether from the flowers and butterflies in a kite-maker's jolly household.

"We could buy some presents!" Santvoort exclaimed with sudden inspiration. "Stuffs for the women to make gowns, and some gay combs. Something for the children; and wine and some confections. The men think well of wine and feasting, Will."

"Aye, we could," said Adams. "We could also throw the money into the harbour. For that is what we should be doing —until we have learnt something of the language, and of the money's value. You could easily pay the price of a house for a stoup of wine to-day, and be none the wiser."

"I'll go out with my host," Santvoort said brightly. "I'll let him buy."

"Note down whatever you can, then," said Adams. "I've a point of lead in the house. It takes well on their paper."

Santvoort went with him to the house for the lead and the paper, and then went shopping with his host.

Adams went in, with his weighted skirts, to Magome.