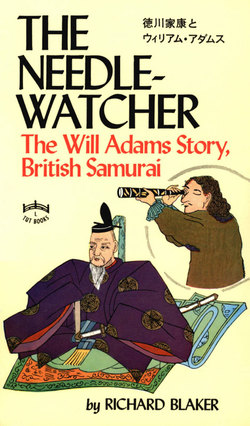

Читать книгу Needle-Watcher - Richard Blaker - Страница 28

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER XIX

MAGOME, in the living-room, waved him to a mat. Adams squatted with a thud and clatter of his money.

The old man's forehead, considered as a feature of his face, was a wedge whose one side was the line of his eyebrows, and the other the old deep scar. One eyebrow was complete, and vivaciously cocked; the other was a little tuft that disappeared into the cavity which was the scar's end. The wedge was all wrinkles, and above it, on the scar, rested the shaved dome which curved away to the tight, stiff top-knot.

"Condescend honourably to sit," said he, the tough old hands resting, as ever, on the sword-hilts.

There was much, he knew, that he should have said; but he knew also that it was in him to say much that should not be allowed to escape in words; so he was not sorry at the soldier's luck that for the moment held his tongue or stopped the ears of the Needle-watcher.

Adams, however, had nought but regret for his dumbness. He knew well enough, already, how glib and easy was the process in this country by which anything could become a present; and it came into his mind as he thanked his smiling host for the hospitality in his gesture and smile, that steps must be taken to prevent any misunderstanding in the transaction that was about to take place.

He solemnly untied the first bundle of great coins in his skirt, keeping it sheltered between his knees. He had got some sense of value from the beaming pleasure of Mitsu as he had appropriated and tied up, on his own judgment, three good tael from the leather sack when the Captain had broken the Shogun's seal and held the open mouth towards the soldier. Forty-three tael, half a dozen mace and some candereen were the Pilot's share of the remaining coins, and he had decided that five tael would be a suitable and a handsome gift to his host. He counted the five slowly out from between his knees into his hand. Making a very distinct, ceremonious gesture of it, he held the money out to Magome. The old man snatched his hands away from their perches and tucked them into his sleeves tightly against his paunch. Obviously, as he smiled and chattered, he could not think of any such thing as the Pilot was suggesting. He was shocked and surprised, though touched and delighted, that the Contemplator of the Needle should have had a thought so generous towards his unworthy self. . . . Adams was satisfied that his own point was clear. Further ceremonial in the matter became superfluous and he merely shoved his hand forward, saying, "Come on, man. Take it!"

No. It was too much for the soldier. He still chattered and objected and withdrew himself from the brilliant and magnificent glare of such generosity; but—perhaps—since——

He withdrew one hand from the folds of the sleeve and coyly, very coyly, stayed the pressure of Adams and took just one coin. It was the least he could do in the face of the overbearing and most amiable insistence of his guest.

"Four more," said Adams. "Here they are."

It was too much. Altogether too much for the astonished warrior. Yielding—since the breast-plate of steel that will turn aside the arrow of an enemy is softer than a silken doublet against the kindness of a guest and friend—yielding, he took a second tael as though it were the most delicate blossom from a fragrant garden.

"Come on, man!" said Adams again. "I mean it. Here they are!"

Protesting, Magome took a third; and protesting further, a fourth. Magically they disappeared about his pocketless person; but at the fifth he absolutely stuck. Adams knew, somehow, that this was indeed the end of it, just as he had known that all the rest had been coquetry. His own attempt at impressive gesture and ceremonial faded utterly in the light of Magome's next performance.

Magome stood and spoke.

There was nothing now in the world to curb an eloquence that had made of him, a quarter of a century earlier, an exile hunted from his own province with a cleft scalp and a cracked skull; for his present listener could hear nothing, but could only see the gestures.

And in them he saw the magnificence of a Lord, the swagger of a ruffian, the austerity of a priest, the gaiety of a boy, the tenderness of a mother and the fealty of a friend.

Adams in turn had to do something. Getting up on his knees, to leave his shirt and its burden undisturbed on the floor, he took Magome's hand in his and shook it.

But he had more to do and he set about doing it. He sat, not as Magome sat on his heels, but flat on his buttocks with his legs stretched out in front of him. Between them he untied the second knot of money, adding it to the first one. He counted the tael into three heaps of ten each and one of nine, setting them in a row at his side. Next to them he set four of the six mace. The remaining two of these and the odd candereen he stuffed carefully into his sash. Then he looked about him. Seeing nothing that could be of the service he required, he removed the few coins he had placed in his sash and tied them again in the skirt of his robe and unwound his sash. Spreading it on the floor he wrapped it slowly over and over round the cylinder made by his thirty-nine tael and four mace. By kneeling over them and patting them, and patting his chest, he cleared any vestige of doubt that could have lingered in the mind of a half-wit as to the ownership of that cylinder. Then he went to the writing-box in the corner of the room and took a sheet of paper and the writing-brush. On the paper he made thirty-nine large strokes and four small ones. He went through a performance of impressive failure in an attempt to push the cylinder into the writing-box, which was obviously too small for it. He looked about the room in search of some other possible receptacle; but the room held, at the moment, nothing but mats, the writing-box and a screen. He indicated the possibility of a cupboard in the wall and Magome smiled, and scuttled away from the room. He returned with a small chest—a sheer slab of polished wood that showed neither join nor lock nor hinges. Setting it down upon the floor, obscuring Adams's view of it with his stooping body and hanging sleeves, he did whatever was necessary to release the lid. He turned to Adams for the money. Adams very solemnly handed him the paper and the writing-brushes. The old man counted the marks, large and small. Below them he wrote his initials or his signature—smiling his approval of the astuteness of the depositor—and handed the receipt back to Adams.

They laid the cylinder on the wrappings that covered whatever other treasures the chest already held, and he pressed the lid back into position.

He took Adams with him to replace the chest under the floor-boards in the room where his sleeping-mat was spread.

He called to the girls as they went back to the other room, and Magdalena followed a few moments after them with drinking cups and rice spirit of the kind that had opened the first dinner.

He was in the highest of humours even before they had sat down to drink; and after two cups of the liquor the words in his breast and his throat that it was useless to utter, produced a discomfort that Adams could see.

Adams, sashless now and pocketless, fumbled for some housing for his receipt. He moved, finally, to stuff it between his skin and the waist of the tight drawers he wore. A sudden, surprised clucking of disapproval on the part of Magome ended in a contemptuous guffaw. He leaned forward and thrust his hand against his guest's bare stomach and ripped the flimsy drawers away, splitting first one leg of them and then the other with two neat movements. Swearing or grumbling or praying, he twisted the rags into a ball between his hands and shouted through the door.

Adams stuffed the receipt into his sock and was, he thought, ready for anything.

He was surprised, however, to see Bikuni in the doorway, listening to a dramatic discourse of which the subject was the rags in the old soldier's hand and—as obviously—that section of himself which the rags had recently adorned. Very humbly the girl took her scolding for the outrage that a guest so honourably distinguished as the Needle-watcher should have gone breeched in the vile garment of a workman or coolie. . . .

Bikuni took the rags from her father and bowed and withdrew. While she was gone, Magome struttingly showed Adams that what the man of any distinction wore beneath his jacket and his sash and his robe and his tunic under-robe was, magnificently, nothing.

The girl returned, and Magome took from her a sash and folded hakama—the loose, skirt-like pantaloons with a thin board in their waist at the stern, wherein a gentleman sometimes walked abroad, wearing them over and not under his robes. He gestured Bikuni towards Adams with the large gesture of gift-bestowing.

Adams took the things and thanked her.

The new sash he wound about his waist, deftly, and exactly as he had learned to do from Mitsu.

Magome smiled and nodded and clucked his approval of the Pilot's skill. He stepped forward to pat the sash and straighten a fold in it; and he adjusted the overlappings of robe and tunic. Then he stood back, caressing the sheathed marvellous blades in his own sash, sad at the thought that in the sash of the Needle-watcher there were none.

From some shadow of ceremony and ritual about them as they dined, and from the cool feeling, one against the other, of his dramatically unbreeched hams, the Needle-watcher knew that he had taken a step with regard to his destiny. The geniality of his host told him while they were both still sober as judges that the step was all to the good; but it told him nothing of its direction.

Magome was generous with his meagre store of wine that night; they drank of it again after the meal; and Adams went to his mat and his coverlet in a mist that glowed with the warmth of hospitality—till it was a black, impenetrable fog.

The fog, he realised, was the language. And even a needle-watcher had nought to do in a fog but hold a steady course till he had got through it, or till it lifted.