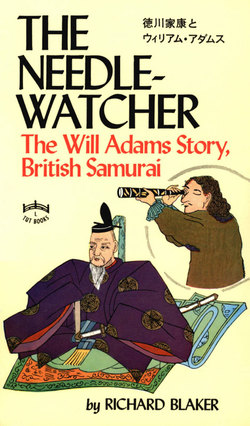

Читать книгу Needle-Watcher - Richard Blaker - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER XIV

SANTVOORT appeared at the house in the morning just as Mitsu was taking Adams with him to the palace. Adams introduced him to his host as the "Hollander" and Santvoort, quite glibly discarding his sandals at the door, found the old man's hand in his sleeve and shook it. For the Dutchman was in high spirits, immensely proud of a new jacket that fitted him amply, cut out and stitched overnight in the household of the kite-maker that lodged him. For it he had given the kite-maker some heavy brass buttons.

"There is no need for the Hollander to come," Mitsu said.

"There is need for him to walk," said Santvoort. "After three weeks aboard. He will wait outside if the Emperor does not require him. He will be quite comfortable sitting in the sun."

"We are guests now, right enough, Will," he said as the three of them turned away from the house. "Something will surely come of it. There is no more of that business of watching us with soldiers and saying us 'Nay' at every turn." He told now of the simple transaction that had given him the coat for buttons. "We could not have done that at the last place. This place is better altogether."

"And well it might be," said Adams. "Mitsu says it is the capital of all the land." He turned to Mitsu. "There would be good merchants here," he suggested, "we could readily sell our cargo."

"Not many merchants," said Mitsu. "Osaka is more the merchant's city. This is a city of soldiers. But as for selling, there will be enough. It is of some selling that the General would see you."

"There-" said Santvoort.

In a mile of walking they had passed carpenters at work in their yards; smiths and weavers and dyers.

"Buying, too, will be easy," said Adams. "There is timber, and the workmen seem good."

It was a trick of their minds, Santvoort's no less than Adams's, that they thought coherently along the alternatives of their destiny without any overlapping of the alternatives themselves. They thought of staying; and in such thinking they accepted the staying and considered it apart from the possibility of anything otherwise. So also when they thought of going they thought of the ways and means only of that going.

Till now, Adams reminded the Dutchman, it was only in the great bridges of Osaka that they had seen timbers that would make a mast.

When they came to the crossing of the canals and moats about the castle itself they saw that in Yedo, too, there was good timber.

They passed sentries who might have been drowsing loafers, drowsing loafers who might have been sentries. Most of the straw-hats tilted up, most of the faces under them cracked into a smile for Mitsu and his charges.

Occupied completely with thoughts of the cargo's market, of masts, of planks, of the twisting of reeds or silk into rope if the country had no hemp, of victualling—and of doing it all at some profit—Santvoort sat down on a stone in the courtyard and Adams went in with Mitsu.

Ieyasu, here, was not the mighty Shogun seated in rich state in a gilded chamber as he had been at Osaka. An older man was with him, and a younger and the three sat together on a mat, talking. There were no formalities beyond a nondescript combination of salute and bow from Adams, who also sat down on the spot indicated by Ieyasu in front of the three.

"He trusts you have found some small comfort in the house of his soldier Magome Sageyu," said Mitsu, who remained standing.

"Aye; thank him," said Adams; "quite comfortable. And I hope he is well."

Thereafter Mitsu became a vehicle that scarcely delayed the speech that passed from one to the other.

Adams wished, said Mitsu, to sell the contents of his ship. Very well. Of the eighteen pieces of ordnance on the Liefde the General would buy sixteen, of which he had need on his walls.

Adams was staggered. Of what use, without ordnance—or with but two pieces—was a ship in seas verminous with Portingals and Spaniards?

Of what use, asked the others quietly, was ordnance on a ship that could not go to sea?

Could not? retorted Adams. The Liefde was a good ship. All he wanted was material, some good workmen and a little time, and he could make her as seaworthy as ever she had been.

There was a pause.

Then words came slowly from leyasu, slowly and deliberately from Mitsu. Interpretership was a trust sacred in the hands of any man of honour. It was an art also, whereby the smile and gentleness or the frowning anger of the principal became at once the smile or the frown of his interpreter.

Mitsu smiled and spoke gently. "When the heart of man is torn between two desires, An-jin, his mind is without a friend. It waits only on the issue of a fight between two enemies. Of these, even the victor emerges weakened by the combat—and is a poor friend. A man in doubt is a man in fetters. Therefore be without doubt. Your ship, An-jin, is not to sail. Not yet."

Adams said, "Enough of this nonsense of buying, and guests, and friendship, then. You have got us. Do as you will. Steal the ordnance. Steal the whole damned ship—cargo and all; but don't talk of pirates and robbers again. Or friends."

The answer came, smoothly and gently. "Beware of anger, Pilot. For, as doubt is a shackle upon the limbs of a man, so is anger a blindness in his eye."

"And thieving is thieving," said Adams, "whatever else you may call it. You say you will buy our ordnance?—but of what use is money to us if we may not buy the things that will put our ship to sea? It is as though you gave us no money—if we may not buy with it what we want."

"Money can buy much besides fittings for a ship."

"But we want no other things," said Adams.

"The fault then is in you," said leyasu. "Not in the money. See how a man in doubt is fettered; he may not even move his hand for the spending of money."

"Oh—take the pieces," said Adams. "But it is by no transaction of buying or selling that you get them from me. They are not mine. I am the pilot, not the Admiral. If you would deal, honestly, it is with him you must deal—the captain. It is nothing to me. I only take his orders."

"And thus you are rid of doubt!" The words came with laughter—not laughter at a man before company which is an insult equal to a spitting in his face; but the laughter of a friend for a friend. "There is no action freer from doubt than an obedience to orders."

Adams said, "If he will sell them, well and good."

"And you?" said Ieyasu. "Will you tell him to sell them? As you told him not to break faith with me and sail with the priest?"

"All I told him then was that I myself would not go with the padre," said Adams. His anger had, somehow, abated; but he was still ready to disagree upon details.

"Did you not realise that it would have been the only way of going?" This was cajolery, not argument.

"Aye," said Adams. "I suppose I did."

"So there is no doubt in you." Ieyasu went on quietly. "This talk of going is only talk; and you will stay—undoubting, as my guest in this inconsiderable city."

"Aye," said Adams. "It looks mighty like it. For here, I suppose, are not even priests and rascal Spaniards to aid us."

"That is true," said Ieyasu. "There come no other foreigners here. All the men here are mine."

"Like our ordnance," said Adams.

"Of a metal every whit as sound," was the smiling answer.

Adams shrugged his shoulders against the defeat this talk held for him. "If I could speak your tongue," he said; "or if you could understand mine, I would have more to say."

"It will come soon enough, An-jin," said Ieyasu. "Lesser men than you have learned to speak our tongue in a very few moons. We will see then what you have to say. In the meantime see your captain and tell him we would buy his pieces."

"He, too, is responsible to others," said Adams. "We are but the servants of a great company. What we have we only hold for them."

"Very well, then," said Ieyasu. "I will hold it in turn for you. Your pieces—the property of your masters—will be safer on the walls of my fortress here than on your ship. More lives stand between them and destruction on these walls than at the waterside. You yourself shall instruct us in their care; and in their use—if your captain will condescend to lend them to me as a friendliness to a friend. As to the other service of which you spoke—to other masters—that, surely, is dissolved by your disasters. You are all guests now—equally. You have no masters other than your host. Take whatever comfort you may find in his hospitality and learn, meanwhile, to speak his tongue."

"Yes," Adams mumbled. "All very well." He was thinking not so much of himself at the moment as of what he would say to the others. For himself there seemed to be a vague reasonableness about it all. He knew now that he was defeated utterly; but, somehow, in the defeat there was no sting. But the telling to others that they were defeated—captain and crew—was another story altogether.

"Shun doubt, An-jin," said leyasu quietly with the voice of Mitsu. "Follow the swing of the needle. Deal with destiny as it is—not as it might be but is not."

Adams replied, mumbling again . . . "All very well to talk . . ."