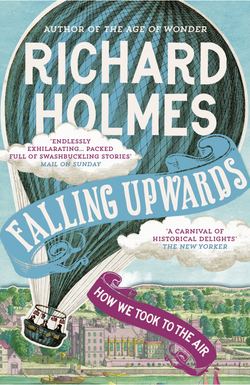

Читать книгу Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air - Richard Holmes - Страница 20

3 Airy Kingdoms 1

ОглавлениеBy the end of the 1820s the early pioneering days were over, and the dream of some universal form of global air transport by navigable balloons had faded across Europe.

Indeed, quite another form of revolutionary transport system was starting to emerge, in the shape of the railway network. The opening of the twenty-six miles of the Stockton to Darlington line in 1825 heralded an era of universal railway building. Five years later, the first genuine passenger service opened between Manchester and Liverpool. From then on, the heavy engineering of the Victorian steam engine, establishing powerful new notions of speed, reliability and a regular ‘time-table’ came to dominate the whole concept of travel.

These weighty considerations were, of course, the exact opposite of what a hydrogen balloon could provide. Victorian ballooning would eventually become the antithesis of the Victorian railway. It would be seen as poetic as against prosaic; as natural rather than man-made. The Victorian railway would mean iron, steam, noise, power and speed, as Turner envisaged in his painting. It would bring ‘railway time’, and a form of mass transport which was both a vital means and a literary symbol of industrialisation. By contrast, ballooning would come to be seen as essentially bucolic, even pastoral. It was silent, decorative, exclusive, and refreshingly unreliable: a means to mysterious adventure rather than a mode of mundane travel.1 fn11

So, at this very time of the railway boom, a new kind of flying was starting to capture people’s imagination. It was marked by the emergence of what might be called the ‘recreational’ balloon. These were increasingly large, sophisticated and well-equipped aerostats, designed to take several paying passengers, and with luck to make a profit for their owners. Though they were commercial propositions, they retained an ineffable romance. They often had ‘royal’ in their names, in deference to the new young Queen Victoria, who came to the throne in 1837.

They were recreational balloons in several senses, constructed and flown by a new breed of balloon businessmen and entertainers, aerial entrepreneurs who regarded themselves as skilled professionals as well as artists of the air. Crucial to their commercial success was the discovery that coal gas, cheap and reliable and easily available from the urban ‘mains’, could be substituted for expensive and unstable hydrogen. Their most memorable flights would also be over urban landscapes.

Drifting silently above London or Paris, or any of the industrialised centres of northern Europe, they granted their passengers a new and instructive kind of panorama. They revealed the extraordinary and largely unsuspected metamorphosis of these cities, with their new industries and their hugely increased populations. What they found spread out below them had never been seen before in history. It was both magnificent and monstrous: an endless panorama of factories, slums, churches, railway lines, smoke, smog, gas lighting, boulevards, parks, wharfs, and the continuous amazing exhalation of city sounds and smells. Above all, what they saw from ‘the angel’s perspective’ was the evident and growing divisions between wealth and poverty, between West End and East End, between blaze and glimmer.