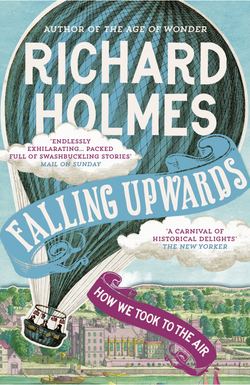

Читать книгу Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air - Richard Holmes - Страница 7

2

ОглавлениеThroughout history, dreamlike stories and romantic adventures have always attached themselves to balloons. Some are factual, some are pure fantasy, many (the most interesting) are a provoking mixture of the two. But some kind of narrative basket always seems to come tantalisingly suspended beneath them. Show me a balloon and I’ll show you a story; quite often a tall one. And very frequently it is a story of courage in the face of imminent catastrophe.

What’s more, all balloon flights are naturally three-act dramas. The First Act is the launch: the human drama of plans, hopes, expectations. The Second Act is the flight itself: the realities, the visions, the possible discoveries. The Final Act is the landing, the least predictable, most perilous part of any ascent, which may bring triumph or disaster or (quite often) farce. The ultimate nature of any particular balloon ascent – a pastoral, a tragedy, a comedy, a melodrama, even a sitcom – is never clear until the balloon is safely back on earth. Sometimes it is not clear even then.

Even the well-known fable of the Cretan engineer Daedalus and his young son Icarus, so often retold as the Genesis myth of flying, is curiously ambiguous in its outcome. It appears originally in Book VIII of Ovid’s long poem Metamorphoses, ‘The Transformations’, completed two thousand years ago, around 8 AD. Having constructed wings for both of them, Daedalus and son launch into the empyrean together, but famously the impetuous Icarus flies too high; the wax joints of his feathered wings melt ‘in the scorching heat of the sun’, and he tumbles down into the sea. Yet this primal legend of flight is more complex than it might appear.

It is often forgotten that in the same Book VIII of Ovid’s poem, Daedalus also has a twelve-year-old nephew (the son of his sister) called Perdix. Perdix is a brilliant and precocious child inventor, loved by all in Crete. But Daedalus, in a crazed fit of grief and jealousy after the death of Icarus, hurls Perdix ‘headlong down from the sacred hill of Minerva’. Yet unlike Icarus, Perdix does not crash to earth and die. Instead, he takes to the air and flies with divine aid: ‘Pallas Athene, the goddess who fosters all talent in art and craft, caught him and turned him, still in mid-air, to a fluttering bird and covered his body with feathers, so the strength of his quick intelligence sprang into his wings and feet.’ He becomes Perdix, the partridge (perdrix in French), a child who has indeed learned to fly successfully – although unlike Icarus he always remains close to the ground, ‘and does not build his nest in mountain crags’.1

What may happen while actually aloft is equally mysterious. Balloons have always given a remarkable bird’s-eye or angel’s-eye view of the world. They are unusual instruments of contemplation, and even speculation. They provide unexpected visions of the earth beneath. To the earliest aeronauts they displayed great natural features like rivers, mountains, forests, lakes, waterfalls, and even polar regions, in an utterly new light. But they also showed human features: the growth of the new industrial cities, the speed and violence of modern warfare, or the expansion of imperial exploration.

Long before the arrival of the aeroplane in the twentieth century, balloons gave the first physical glimpse of a planetary overview. Balloons contributed to the sciences and the arts that first suggested that we are all guests aboard a unified, living world. The nature of the upper air, the forecasting of weather, the evolutions of geology, the development of international communications, the power of propaganda, the creations of science fiction, even the development of extra-terrestrial travel itself, are an integral part of balloon history.

But there are also stranger, existential elements, far less easy to define. The mental release, the physical heart-lift, the calm perilous delight of ballooning – an early aeronaut described it as ‘hilarity’ – is an absolute revelation, but one not easily or convincingly described. I have tried to capture its spirit indirectly, by tying together this cluster of true balloon stories and colourful tales, from the vast ‘history and lore of aerostation’, in the hope that they will bear us aloft for a little while.

While airborne, they may also provide a new perspective. The vulnerable globe of balloon fabric is itself symbolically related to the vulnerable globe of the whole earth. There is some haunting analogy between the silken skin of a balloon, the thin ‘onion skin’ of safety, and the thin atmospheric skin of our whole, beautiful planet as it floats in space. This thin breathable layer of air is not much more than seven miles thick – as balloonists were the first to discover. In every way, balloons make you catch your breath.