Читать книгу Ruairí Ó Brádaigh - Robert W. White - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

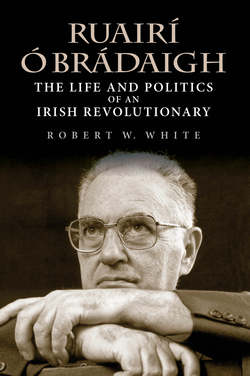

Matt Brady and May Caffrey

ANGLO-IRISH WARS in the seventeenth century consolidated English power over Irish affairs and placed a minority but loyal Irish Protestant elite in control of the majority Irish Catholic population. The Protestant Ascendancy ruled Ireland from their base in Dublin, but their greatest numbers were in the northeast portion of the province of Ulster. It was here that the Plantation of English and Scottish settlers into Ireland in the seventeenth century was most successful. In the 1790s, anti-English agitation in Ireland, as organized by the United Irishmen, adopted a Republican political philosophy. They tried to unite Catholic, Protestant, and Dissenter to establish an Irish Republic. They rebelled in 1798 and failed. Rebellions against English and British power in Ireland continued into the nineteenth century: by remnants of the United Irishmen in 1803, by the Young Irelanders in 1848, and by the Fenians at various points in the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s. These rebellions were complemented by largescale social protest movements that also challenged the status quo. In 1829, agitation led by Daniel O’Connell resulted in Catholics being granted the right to hold seats in Parliament. In the 1870s and 1880s, Charles Stewart Parnell and others involved in the Land League forced landlords, if only slowly, to return lands confiscated from the Irish people in the seventeenth century. Parnell, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party at Westminster, was also a key proponent of a Home Rule for Ireland Bill. If enacted, the bill would not create an Irish Republic, but it would limit the power of the Protestant Ascendancy and give Irish people significantly more control over Irish affairs.

It was into this context that Matt Brady was born in 1890 in North County Longford in the townland of Gelsha, near Ballinalee. He was the youngest of eight children, and in a time of high infant mortality, only he and his siblings Hugh and Mary Kate lived to adulthood. Then, as now, the area was filled with trees, bushes, small farms, and little villages. Matt’s father, Peter Brady, was married to Kate Clarke and worked a twenty-acre farm. Folklore has it that the Bradys were driven from Ulster by Orangemen. They were in North Longford by at least the 1840s, when Peter’s uncle died of typhus during the famine. Peter Brady was active in local politics and is remembered for buying newspapers and reading them to his neighbors, giving them the news on Parnell, the Fenians, and other events. He was active in the Land League, and at one point he chose to go to jail rather than pay a fine for agitation.

County Longford is strategically located in the Irish midlands where the provinces of Leinster, Ulster, and Connacht come together, and it has a long military history. In the 1640s, General Owen Roe O’Neill, who was home from the Spanish Army, trained his Army of Ulster at the juncture of the three provinces. In 1798, a French expedition, under the command of Jean-Joseph Amable Humbert, invaded Ireland in support of the United Irishmen. Humbert landed at Killala in County Mayo and marched his troops through Mayo, Sligo, and Leitrim and into Longford, where he confronted British General Lake in what became known as the Battle of Ballinamuck. It is estimated that 500 insurgents fell in the battle. As Humbert described it, he was “at length obliged to submit to a superior force of 30,000 troops.” The French were taken prisoner; the Irish were slaughtered. Among those captured and hanged were the United Irishmen Bartholomew Teeling and Matthew Tone, the brother of Wolfe Tone, who is considered the founding father of Irish Republicanism.

The effects of Ballinamuck weighed on the local peasantry and small farmers, who had risen against the Crown and paid a high price for it, and on the local elites, who feared it might happen again. Seán Ó Donnabhhin, an Irish scholar who worked on an ordnance survey in North Longford, described the people of the area in an 1837 letter from Granard as “poor, and what is worse, kept down by the police.” One of the few Irish soldiers to survive the battle was Brian O’Neill. People like him kept the memory of the battle alive, and it became a symbol of local resistance to British injustice. O’Neill’s grandnephew, James O’Neill, was born on March 1, 1855, and over the course of his long life he was a keeper of the flame of Ballinamuck, a direct link between 1798 and decades of political activity in Longford, until his death in 1946. A contemporary of Peter Brady, he was involved in the Land League, was president of the Drumlish and Ballinamuck United Irish League, and was later active in Sinn FCin with Matt Brady.

In 1913, Matt Brady moved from Gelsha to Longford town and became a rate collector for the County Council. The town developed on the Camlin River; in 1913 a main feature was two military barracks, one for cavalry and the other for artillery. The barracks indicated Longford’s strategic location and a tradition of resisting the Crown’s authority. It was a prosperous town, and architecturally it was and is dominated by the facade and tower of St. Mel’s Cathedral. The foundation stone for St. Mel’s was laid in May 1840, but the building was not completed until the 1890s. In 1914, after Matt’s brother Hugh left for the United States, Matt continued his work for the county and maintained the small farm at Gelsha. World politics would soon set in motion events that would directly affect both Matt Brady and Longford.

When it became apparent that Home Rule would pass in Westminster, anti-Home Rule Unionists in Ulster organized the Ulster Volunteer Force and began drilling. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, heirs of the Fenians, countered this by forming the Irish Volunteers. When World War I began, Unionists supported the war effort and the Ulster Volunteer Force joined the British Army en masse. John Redmond, Parnell’s successor as leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, encouraged the Irish Volunteers to do the same, splitting the Volunteers.

In August 1914, the Irish Republican Brotherhood’s Supreme Council met and determined that Ireland’s honor would be tarnished if no fight was made for an Irish Republic during the world war. The Irish Republican Brotherhood planned a rebellion to coincide with the importation of arms from Germany at Easter 1916. The arms were to arrive in County Kerry, then be distributed throughout the south and west of Ireland. Instead, Irish Volunteers missed their rendezvous with a German Steamer, the Aud, which was eventually spotted by the Royal Navy. The crew scuttled the Aud, and her cargo, at the entrance to Cork Harbor. When word of the lost arms reached the rebel organizers, confusion set in and the Rising was postponed from Easter Sunday until Easter Monday. Rebels seized the General Post Office and other strategic buildings in Dublin, and Patrick Pearse, “Commander-in-Chief of the Army of the Republic and President of the Provisional Government,” stepped forward and proclaimed the Irish Republic. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) took up positions throughout Dublin. So did the Irish Citizen Army, led by James Connolly, a socialist critic and labor organizer, who had formed the small (approximately 200-member) Citizen Army in 1913 as a defense force for workers during a bitter lockout.

British reinforcements quickly suppressed the rebellion; within a week, several parts of the city were reduced to rubble and 450 people were dead. The rebels’ surrender was followed by large-scale arrests in Dublin and in the provinces, and general courts-martial were set up. One hundred and sixty-nine men and one woman, the Countess Markievicz of Connolly’s Citizen Army, were tried and convicted by courts-martial. The Easter Rising’s leaders—including the signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, Tom Clarke, Patrick Pearse, James Connolly, Sein Mac Diarmada, Eamonn Ceannt, Thomas McDonagh, and Joseph Plunkett—were executed. Over 1,800 men and five women were sent to Frongoch internment camp in Wales. Eight of them were from County Longford; three were from Granard.

Internees were quickly released; 650 after a few weeks, more in July, and the rest by Christmas 1916. They were welcomed home by crowds and bonfires. The prisoners had not wasted their time in the camp. Placed together in one location, they formed friendships, organized themselves, and plotted. When they were turned loose, they joined the political party Sinn Féin, the Irish Volunteers, or both. When it was announced that there would be a by-election for the North Roscommon seat at Westminster in February 1917, the Republicans had a chance to find out how much support they had. Count Plunkett was put forward as the representative of the new Irish nationalist direction in opposition to the Irish Parliamentary Party candidate. A prominent and respected member of the community, he was director of the National Museum, a papal count, and the father of the executed 1916 leader Joseph Plunkett. He ran as an independent, heavily supported by Sinn Féin, and won handily. After some pressure from Sinn FCiners, he declared he would follow Sinn Féin’s policy of not taking his seat at Westminster. This decision continues to influence Irish politics.

In May 1917, there was another by-election, this time in South Longford. Mick Collins, who had been interned in Frongoch, was a conspiratorial genius. He arranged to have Joe McGuinness, who was imprisoned in England, nominated as the Sinn Féin candidate. McGuinness, a Dublin draper, was a native of nearby Tarmonbarry, and his brother, Frank, owned a small shop in Longford town. The campaign slogan was “Put him in to get him out.” Republican Ireland descended on Longford; among those speaking on behalf of McGuinness were Margaret Pearse, widowed mother of the executed brothers Patrick and Willie Pearse, Count Plunkett, and Mrs. Desmond Fitzgerald, whose husband, a 1916 veteran, was in an English jail. Count Plunkett told one crowd, “Every vote for McGuinness [is] a bullet for the heart of England.” The public was presented with two distinct choices, the moderate work-with-the-system approach of the Irish Parliamentary Party versus the radical challenge-the-system approach of Sinn Féin. McGuinness won by thirty-seven votes. Around this time, Matt Brady joined the Irish Volunteers.

When McGuinness was released from prison, a rally in Longford brought together a who’s who of Irish Republicans, including McGuinness, Count Plunkett, Arthur Griffith, am on de Valera, and Thomas Ashe. Griffith was the founder of Sinn FCin and the prime source of its abstentionist tactics; that is, the refusal of Republican elected officials to take their seats at Westminster. De Valera was the most senior 1916 rebel who had not been executed. In 1916, Ashe had led attacks on Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks in North County Dublin and directed a pitched battle with the RIC outside Ashbourne in County Meath. Collectively, they were key actors in a series of dramatic political events. Matt Brady was a witness to and participant in these events and probably heard Ashe introduced as “Commandant Thomas Ashe of the Irish Republican Army.” Soon after the rally for McGuinness, under the Defence of the Realm Act, Ashe was charged with attempting to cause “disaffection" among the people while making a speech at Ballinalee, County Longford. He was sentenced to one year’s imprisonment at hard labor and joined about forty other prisoners in Mountjoy Prison in Dublin. The prisoners attempted to distinguish themselves from the criminal population by requesting a number of special privileges, including unrestricted conversation, optional work, classes for study, and no association with ordinary criminals. When the privileges were refused, they embarked on a hunger strike. The prison authorities countered by force-feeding them, but liquid was pumped into Ashe’s lungs instead of his stomach, causing his death in September 1917.

Republicans from throughout Ireland attended the funeral; years later, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh recalls his parents’ account of the event. The First Battalion (Ballinalee) of the Longford Volunteers, including Matt Brady of the Colmcille Company, marched eight miles to Longford town to catch a special train to Dublin. There were so many passengers that extra carriages were attached as the train progressed. The funeral, an open display of contempt for the power of the authorities, brought the city to a standstill. After a volley of shots was fired over the coffin, the oration was given by Mick Collins. He was brief, but powerful: “Nothing additional remains to be said. The volley which we have just heard is the only speech which is proper to make above the grave of a dead Fenian.” On detail was Matt Brady and his comrades in the Colmcille Company of the Longford Battalion, Athlone Brigade, of the Irish Volunteers. As did many others, Brady took his turn “on guard over [the] corpse in the city hall … and then on duty at [the] funeral.”

About this time, May Caffrey was an 18-year-old living in County Donegal. She was the daughter of John Caffrey, a municipal inspector for Belfast Corporation, and Jeanne Ducommun. Caffrey met Ducommun in London, where he was attending classes while she was working as a governess. He was an Irish Catholic interested in learning French. She was a Swiss Calvinist who was fluent in French, English, and German. In spite of, or perhaps because of, their different backgrounds, a relationship blossomed. They married and moved into a house on Clonard Gardens in Belfast. One of her first experiences there was watching the aftermath of a July 12th march commemorating the victory of the Protestant army of William of Orange over the Catholic army of James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. She was amazed at the rioting. Their daughter, May Caffrey, was born in Belfast in 1899. In 1906, the family moved to Armagh City, where John Caffrey took a job as headmaster of the Technical Institute. May would later tell her children about how she always had to walk to primary school with a group of other children, for she had to pass through a Unionist area and her parents feared she would be attacked. In 1908, the family moved to Donegal Town, where John Caffrey became county engineer. He also became active in Sinn Féin. He attended the Dublin funeral of the Irish-American Fenian O’Donovan Rossa in 1915 and heard Pearse’s famous oration there. In the 1918 national election, he seconded l? J. Ward, Sinn FCin’s candidate for South Donegal, on Ward’s nomination papers. (Ward was elected). Caffrey’s children followed his politics.

Like Matt Brady, May Caffrey was a participant in the dramatic political events in Ireland. She was a member of the Gaelic League and was the captain of the first branch of Cumann na mBan, the women’s wing of the Republican Movement, in Donegal town. She also organized the hinterland, cycling to Mountcharles and Frosses and other places. At one point, a local priest complained to her father that she was drilling the servant girls. The priest indicated that not only were her politics wrong but she was consorting with people beneath her. Her father ignored him and supported her.

As Sinn Féin, the Irish Volunteers, and Cumann na mBan grew and de Valera, Arthur Griffith, Mick Collins, and others toured the country, the authorities became concerned. Collins was arrested in Dublin in March 1918, transported to Longford, and charged with having “incited certain persons to raid for arms and carry off and hold same by force" in North Longford. He was found guilty and sent by train to Sligo Jail. In the same month, John Joe O’Neill (son of James O’Neill), was charged with drilling a squad of young men at Ballinamuck. Crowds of Sinn Féiners regularly attended the court proceedings, protested the results, and welcomed the prisoners home when they were released. According to the Longford Leader, among those who met Collins when he was released from Sligo Jail was Hubert Wilson, a former Frongoch internee and Matt Brady’s battalion commander. Matt Brady was likely there, too.

In April 1918, the political situation became especially serious. The House of Commons voted to extend conscription to Ireland. Nationalist Ireland, Republican or not, was opposed. Most of the Catholic clergy were opposed. In Donegal, May Caffrey watched the local Hibernian priest share a platform with members of the Irish Parliamentary Party and Sinn FCin, united in opposition to conscription. In Longford Town, Sinn Ftiners and Irish Parliamentary Party members shared the platform in a public protest. Energized by the crisis, Matt Brady and his comrades “organised resistance to conscription" in their area. In Ballinalee, Sedn Mac Eoin, who had been appointed commander of the local unit of the Irish Volunteers by Mick Collins, was able to recruit a hundred people in one day. Mac Eoin later became a central figure in Matt Brady’s life as a guerrilla leader transformed into a leading politician.

World War I ended in November 1918, and the British government called a national election in December. Sinn Féin seized the opportunity and in a stunning victory won seventy three of the Irish seats at Westminster. The Irish Party, representing constitutional Irish nationalists, took six seats, and the Unionist Party, representing Protestant and Northeast Ireland, took twenty-six seats. In Longford, Sinn FCin polled extremely well and Joe McGuinness was easily re-elected. Among the others elected was Countess Markievicz, in Dublin. She was the first woman to be elected in a British parliamentary election.

In January 1919, the elected Sinn Féin representatives put their abstentionist principles into action. Instead of going to London as Irish representatives to a British government, they formed a revolutionary government in Dublin, called Ddil Éireann (Parliament of Ireland). Éamon de Valera, president of Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers could not attend; he was imprisoned in England. In his lace, Cathal Brugha, a 1916 veteran noted for his devotion to the Republican cause-he had suffered many bullet wounds-was elected president of Ddil Éireann. Members of the DG1 viewed themselves as the Parliament of the Irish Republic, “proclaimed in Dublin on Easter Monday, 1916, by the Irish Republican Army acting on behalf of the Irish people.” Ireland was sliding into a revolutionary situation. Sinn FCin courts and arbitration boards were established and their decisions were accepted by the people. On the day Dáil Eireann was formed, Irish Republican Army volunteers in Tipperary killed two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary and seized a cartload of explosives.

Under the authority of Dáil Éireann, the Irish Volunteers formally became the Irish Republican Army. The IRA in North Longford reorganized under the command of the Longford Brigade. Sein Mac Eoin became Ballinalee battalion commander. John Murphy was his vice-commandant and SeQn Duffy his adjutant. Battalion companies were located at Edgeworthstown (Mostrim), Killoe, Mullinalaughta, Drumlish, Ballinamuck, Colmcille, Granard, Dromard, and Ballinalee; Matt Brady was a lieutenant with the Colmcille Company. Similar reorganizations occurred across the country, and the IRA began to flex its muscles. Se6n Mac Eoin led a raid into County Cavan that recovered shotguns impounded by the RIC. In Limerick, the IRA tried to free a hunger-striking Republican prisoner from the hospital. The prisoner, a police officer, and a prison guard were shot dead and another guard was wounded. The authorities proclaimed Limerick a military area, and tanks and armored cars paraded the streets. By the end of April, Counties Limerick, Roscommon, and Tipperary were under British military control.

On Sunday, April 27, 1919, one week after Easter, there was an aeraiocht in Aughnacliffe, a sort of outdoor contest and sports festival with bands and dancing. Such events build community spirit and allow people to enjoy the day. Several Sinn FCin members spoke there, including Joe McGuinness. In the evening, there was a concert. Given the political climate, extra police were brought into the area. Unknown to them, Se6n Mac Eoin was using the event for an IRA Brigade Council meeting.

As the concert was starting, Matt Brady and Willie McNally, who were both in the IRA, went for an evening walk with Phil Brady, a Sinn FCin candidate in the upcoming local election. At about 9 PM, they left Phil Brady “on his way home" and were returning to the concert when they saw two RIC constables, Fleming and Clarke, cresting a hill on bicycles. The off-duty constables were returning to their barracks at Drumlish. Brady and McNally decided to seize their weapons. Each jumped a constable; the men starting wrestling, but McNally had trouble with his man. A shot rang out and McNally, hit in the head, collapsed. The RIC men then turned on Matt Brady, shooting him five times. Frightened and angry, they smashed the butts of their rifles into Brady’s and McNally’s faces. Phil Brady heard the shots and turned back to investigate, passing Fleming and Clarke running with their bicycles in the other direction. He found Matt Brady riddled with bullets. He had been hit at least twice in the chest and his left thigh was a mess. Bullets had gone through both hands. McNally was bleeding from a nasty but not dangerous wound over his left eye. Phil Brady ran to get help, shouting that there had been a murder. As more people arrived, they discovered that both men were still alive.

Seán Mac Eoin arrived quickly and took charge. He sent Seán F. Lynch, a Sinn FCiner involved in the court system, in search of a doctor and oversaw the removal of Brady from the edge of the road to the kitchen of a local house. Two local physicians arrived and began treating the wounded men, and the RIC returned. A district inspector announced that “under the authority of the Crown" he was going to arrest the two men. Mac Eoin responded, “under the authority of the Irish Republic,” that they would not be arrested. He revealed that he was armed and the RIC withdrew. The incident was indicative of the growing conflict in Ireland.

The next day, as IRA volunteers watched over him, Matt Brady was moved by British military ambulance to the Longford Infirmary, where he recovered slowly, under the watchful eyes of both the IRA and the RIC. In October, Mac Eoin was alerted by Crown Solicitor T. W. Delaney that a warrant was to be issued for Brady’s arrest. The IRA got there first and moved him to the Richmond Hospital in Dublin, under the care of friendly physicians. Mac Eoin was probably also the source of a Long-ford Leader article that gave Matt Brady a cover story that explained his injuries:

On Thursday forenoon as Mr. Matthew Brady, a well-known Longford horseman, was riding a thoroughbred into town the horse slipped opposite the pump in the Market Square and threw him violently to the ground. Blood gushed from his mouth and nose and he was rendered insensible. A large crowd quickly collected and the priest and doctor were sent for. Rev. Father Newman, Adm., on arrival considered the case so bad that he anointed the injured man on the spot. Subsequently a motor car was procured and the priest and Mr. E H. Fitzgerald, U.D.C., took him to the Co. Infirmary, where he lies in a very precarious state.

From the spring of 1919 the IRA grew quickly and its capabilities expanded rapidly. In Dublin, it was led by Mick Collins, who was ruthless. On Sunday morning, November 21st, 1920, IRA men under his direction broke into homes and hotel rooms and executed fourteen suspected British spies. Some were shot in front of their wives. That afternoon, also in Dublin, British forces took their revenge by firing indiscriminately into a crowd at a football match in Croke Park, killing twelve and wounding sixty. In the countryside, the IRA was especially active in Cork, Tipperary, Clare, Kerry, Limerick, Roscommon, and Longford. Noteworthy IRA leaders were Tom Barry in Cork and Sein Mac Eoin in Longford. Barry directed the IRA in battles at Kilmichael and Crossbarry. His policy was to burn out two pro-British homes for every proRepublican home burned out. Sein Mac Eoin directed the IRA in what became known as the Battle of Ballinalee. In October 1920, the IRA executed an RIC inspector in Kiernan’s Hotel in Granard. In response, British auxiliary troops, in spite of fire from Mac Eoin’s men, torched buildings in the town. A few days later, the auxiliaries set out on a reprisal raid on Ballinalee. Alerted to what was coming, Mac Eoin arranged an ambush, killing several auxiliaries.

Mac Eoin’s exploits became the stuff of legend. In January 1921, he was staying with sympathizers when the home was raided. He escaped, but an RIC district inspector was killed. Mac Eoin then led another guerrilla ambush at Clonfin, during which several British forces were killed. In March 1921, after visiting IRA general headquarters in Dublin, where he met with Collins and Cathal Brugha, Mac Eoin was arrested on the train at Mullingar. He tried to escape and was wounded for his efforts. In prison, he was elected as a Sinn Féin T D (Teachta Dila, member of the Diil) to the Second Dáil Éireann. In court, he was charged with murder. He fought the charge but was found guilty and sentenced to death. Twice Mick Collins tried to break him out of prison. Mac Eoin’s reprieve came when the IRA and British authorities entered into a dialogue that led to a truce and Collins and am on de Valera insisted that he be released. At the first session of the Second Dáil Éireann in August 1921, IRA commander and rebel politician Sein Mac Eoin was granted the honor of proposing de Valera not as president of the Dáil but as president of the Irish Republic.

Matt Brady missed direct involvement in Mac Eoin’s rise to fame. He rode out the Anglo-Irish War (also known as the Black and Tan War) in hospitals in Dublin under the nom de guerre Tom Browne. It was not an easy existence. RIC and British troops were in and out of the hospitals as patients; when he played cards he would hold his hand so that the obvious bullet wound there was not recognized. The hospitals were also raided regularly. He was moved at various points to the Mater Hospital, to Linden Convalescent Home, and to private homes. There were some problems with hospital staff. A nurse at Richmond Hospital reported to the secretary that Brady suffered from a gunshot wound, not the kick of a horse. Dublin Castle, the seat of British power, got the report, but Mick Collins had agents there. When the British arrived, Brady’s hospital bed was empty. The IRA ordered the hospital secretary to leave Ireland within twenty-four hours and the nurse had her hair cropped.

Matt Brady’s presence in Dublin was an open secret among Longford Republicans. He was “available" for his officers, and engaged in “I.O. [Intelligence Officer] work in [the] Mater and Richmond Hosp.” Certainly wounded RIC and British troops were a source of information that he passed along. Longford people visited him, including Joe McGuinness’s wife. While “in his own keeping,” he followed the revolutionary situation in Dublin. From the Mater he watched cabs and lorries arrive with prisoners at nearby Mountjoy Prison. He later recalled for his children a demonstration outside the prison as six IRA members were hanged there, in pairs, on March 14, 1921, two at seven, two at eight, and two at nine in the morning.

Also in Dublin at this time was May Caffrey. A graduate of the St. Louis Convent in Monaghan, she spent a year back in Donegal studying Irish and then qualified for the National University in Dublin. On campus, she majored in commerce and played camogie, which is similar to hurling. She was on the 1921 team which won the prestigious Ashbourne Cup; the team photo is proudly displayed in Ruairí Ó Brádaigh’s home. Her teammates included fellow Republicans, including the sister of IRA member and future Taoiseach (prime minister) SeQn Lemass. Off campus, she transferred to Dublin Cumann na mBan. Her brother Jack was also at the university and in the IRA; during holidays, she continued to organize Cumann na mBan in Donegal. As a Cumann na mBan volunteer in Dublin, she helped provide packed lunches for Sinn FCiners on polling day in the local council elections in 1920, helped hide “wanted men, and marched in formation to protest meetings and demonstrations outside prisons during hunger strikes and executions. It was standard practice for RIC men based in the countryside to visit Dublin and help the police identify people from their areas who might be on the run or visiting on business; Sein Mac Eoin was captured returning to Longford from an IRA meeting in Dublin. As a counter, the IRA asked people from the country living in Dublin to identify these RIC officers. May Caffrey was asked to identify an inspector from Donegal who was expected to arrive in Dublin on a particular train, res sum ably so the IRA could assassinate him. She was at the station with the IRA when the train arrived, without the RIC officer.

In July 1921, the British entered into a truce with the IRA, presenting an opportunity that brought Matt Brady and May Caffrey together. Matt, under relaxed conditions, transferred to Longford County Home and took a job as a steward. May, who had finished her degree in commerce, was teaching in Bray, County Wicklow. The job of secretary to the County Longford Board of Health became available, and they met when both took the civil service examination. With her degree, May Caffrey was better qualified and she got the job, commencing December 5, 1921. Her letter of appointment was signed by Liam T. Cosgrave, Aire Rialtais PLitiliil (minister for local government) of the Second DLil Éireann. She took up residence in the County Home. Among her duties were the registration of births, deaths, and marriages in County Longford and sending board meeting minutes to the department of local government of the stillrevolutionary Ddil Eireann via a “cover address" in Dublin.

In 1920, Westminster passed the Government of Ireland Act, which created two Home Rule Parliaments in Ireland, one in Belfast for the six northeastern counties and one in Dublin for the rest of the country. Republicans rejected the bill, but unionists immediately formed a government for Northern Ireland, with Sir James Craig as prime minister. In 1921, with a truce and negotiations under way, Republicans believed they could reunite the country and achieve international recognition of the Republic. Instead, in London, representatives of DLil Eireann—including Arthur Griffith and Mick Collins but not am on de Valera—signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty on December 6, 1921. The Treaty confirmed partition, contained an oath of allegiance to the British monarch, and placed the 26-county Irish Free State firmly in the British Commonwealth.

Republicans split over the treaty, which was ratified by the DLil. Protreaty Republicans included Mick Collins, Arthur Griffith, and Seán Mac Eoin. Mac Eoin, in the DG1, seconded Arthur Griffith’s motion “that Ddil Éireann approves of the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed in London on December 6th 1921.” Éamon de Valera led the opposition. When it was ratified, he resigned as president of the Republic, moving Ireland from rebellion against the British government and closer to civil war. Arthur Griffith formed a pro-treaty ministry, and Mick Collins became president of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State. The anti-treatyites refused to recognize the authority of the new government. Matt Brady and May Caffrey sided with de Valera and the anti-treatyites. Brady was a determined man. His injured leg was rigid and shortened by several inches and he was forced to wear a surgical boot and walk with a cane, but he was still a “Brigade Staff" officer in the IRA. Prior to the treaty he was “preparing forms for intelligence reports from units and indexing correspondence [of] GHQ Brigade and Gen Staff.” After the treaty, he “left Brigade Head Q’s … and started organizing against [the] Treaty.”

1921 letter from Liam Cosgrave appointing May Caffrey secretarylregistrar of the County Longford Board of Health. Ó Brádaigh family collection.

In Dublin, IRA (anti-treaty) forces established their headquarters in the Four Courts, the country’s legal center. The Free State government demanded that they surrender. They refused, and civil war broke out. The IRA was disorganized from the start, and the Free State forces, backed by the British, drove them from Dublin and pursued them into the countryside. In August, Arthur Griffith died of a heart attack and Mick Collins was killed in an ambush in Cork. Liam Cosgrave, 1916 veteran and the person who appointed May Caffrey as secretary in Longford, took over as president of the Irish Free State. Attitudes on both sides hardened. The 26-county Third Dáil of the pro-treatyites, referred to as Leinster House (where it met, in Dublin) by the anti-treatyites, granted the Free State government the power to impose the death penalty. Executions led to reprisals, which led to more executions. On December 8, 1922, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, four prominent anti-treaty Republicans who had been imprisoned without charge or trial for five months-Liam Mellows, Rory O’Connor, Joe McKelvey, and Richard Barrett-were taken out and shot. Between November and May 1922–1923, more than eighty Republican prisoners were executed. Sein Mac Eoin, a general in the Free State Army, had under his command Athlone Barracks. Five antitreaty Republicans were executed there in January 1923.

In Longford, most of the IRA activists supported Mac Eoin, but there was enough opposition that Mac Eoin singled out Sein F. Lynch in a letter, complaining of Lynch’s anti-treaty activities and noting that “it is time to relegate this man to his proper sphere of duties.” Lynch’s brotherin-law, Tom Brady, also rejected the treaty and tried to reorganize the IRA. The IRA was beaten down in Longford and elsewhere, however. Liam Lynch, its chief of staff, was killed in action in April 1923. Soon after this, de Valera met with Lynch’s successor, Frank Aiken, and they ended the fight. De Valera issued a famous statement to the “Soldiers of the Republic, Legion of the Rearguard" and declared that “[the] Republic can no longer be defended successfully by your arms.” Aiken issued a cease-fire order to soldiers still in the field. Thousands of anti-treaty Republicans were in prison, and still more faced prison if they surfaced. Tom Brady remained on the run until 1925. Militarily, the cost of the Civil War was relatively small, with probably less than 4,000 casualties. Politically, the Civil War created bitter political divisions. Sinn Féin remained the primary opposition party, but they refused to participate in the Free State Parliament. For them, the Second Dáil Éireann remained the true government of the Republic and Free Staters were traitors who had sold out the Republic for political power in a truncated, unfree Irish state. Abstention from Westminster had led to the creation of Dáil Éireann. Abstention from Leinster House, site of the Dublin government, left Liam Cosgrave and the pro-treatyites in unchallenged control of the Irish Free State.

As for Matt Brady and May Caffrey, they found each other in the midst of the truce. They were a perfect match—almost. She was a Cumann na mBan veteran, he was an IRA veteran. Each of them rejected the treaty. They were both ardent proponents of the Irish language. Yet May’s parents worried about the future of their young healthy daughter who was involved with a man nine years her senior who had not, and probably never would, recover from devastating war wounds. Her sister Bertha told her in fun, “You are running around with a broken soldier.” May was unhappy with the comment. Complicating their situation, each was employed at the Longford County Home. An employee there was not allowed to supervise the work of one’s spouse. If they married, one of them would be out of a job.

For four years they wrestled with these issues. In considering their options, they enlisted the support of the most powerful person they knew, Major General Sein Mac Eoin. Mac Eoin had saved Matt Brady’s life and kept him out of harm’s way as he recovered. While they differed totally in politics, they respected each other, and with May Caffrey the three of them had a personal relationship that transcended their political differences. This is clearly evident in letters found in Mac Eoin’s papers. Unfortunately, the best that Mac Eoin could do was to give an assurance that if May Caffrey resigned her job, Matt Brady would receive “the fullest possible consideration" for the position of superintendent assistance officer at the County Home. Making the best of a difficult situation, Matt Brady resigned his job. May Brady would be the breadwinner in the family.

They were married on August 26, 1926, at Castlefinn, County Donegal, where her parents lived. They passed through London on their honeymoon. May later recalled the trip for her children, finding humor in Matt’s reaction. She enjoyed the sights, but he instinctively wanted to get out of the place as fast as possible; as far as he was concerned, England was the fountainhead of all that was bad in the Irish world. They moved on and visited her relations in Switzerland. When they finally arrived back in Longford, May went to work as the secretary of County Longford Board of Health. Matt was unemployed but helped out as she went about her business, and they looked forward to raising a family.

Wedding photograph of May Caffrey and Matt Brady, August 1926.6 BrMaigh family collection.