Читать книгу Ruairí Ó Brádaigh - Robert W. White - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

Derrylin, Mountjoy and Teachta Dála

DECEMBER 1956—MARCH 1957

IN LATE DECEMBER 1956, Noel Kavanagh brought together the Teeling Column, including Ó Brádaigh’s section and Charlie Murphy, who was down from Dublin. Bases had been established, and the column spent the nights of December 28th and December 29th in the field, planning their next move. Kavanagh decided to attack the RUC barracks in Derrylin in South Fermanagh. It would be a return visit; the smaller column had attacked the barracks on December 14th. With the addition of Ó Brádaigh’s section, Kavanagh hoped that the barracks could be destroyed.

On Sunday night, December 30th, Kavanagh arranged for a local IRA unit to block the roads into Derrylin, which would slow down RUC reinforcements. The column traveled on foot into the village and split into two groups, a cover party and an assault team. Ó Brádaigh, who was in charge of the cover party, had a Bren light machine gun. The volunteers with him were armed with Lee-Enfield rifles captured from the British Army in the raid on Armagh military barracks in June 1954. Kavanagh was in charge of the assault team. Seven RUC men were inside the barracks.

The barracks sat on ground about five feet higher than the road that fronted it. Along its sides and in back were trees and thick vegetation. The cover party set up on a grass margin of the road and took cover behind the trees growing through a boundary fence between the road and the barracks. The assault team crept up to the barracks. At about 10:20 in the evening, the RUC men were sitting around the fire listening to the Radio Éireann news bulletin when Ó Brádaigh’s group opened fire, shooting through the windows and front door. Constable John Scally was hit in the back in the first burst of fire. He suddenly stood up and fell to the floor, groaning. Shots poured into the door and windows of the station as RUC men ran to help Scally or get up the stairs to see what was going on.

There was a brief lull, and the IRA called for those inside to surrender. The RUC men responded by returning fire through the second-floor windows. In front of the boundary fence was a shallow furrow filled with water. The return fire hit the water, which splashed Ó Brádaigh on the forehead. It was his first time under fire and his immediate thought was, “That bastard’s shooting at me!” He and the rest of the cover party kept firing; the shooting waxed and waned as volunteers moved about, reloaded, and fired.

Kavanagh and Pat McGirl (no relation to John Joe McGirl) placed a homemade mine-a sack filled with gelignite-against the door of the barracks. While McGirl prepared the fuse, Kavanagh ran on and shot out the front light with his Thompson machine gun. He then heard the radio room above him. One of the constables, Cecil Ferguson, was calling for help. Kavanagh tossed a grenade through the second-story window and went back for another mine. The grenade went off, destroying the radio and blowing debris back out the window. The cover party continued firing. Kavanagh arrived with a second mine as McGirl lit the fuse of the first. He dumped the mine and ran as the first one went off, blowing in the door and demolishing the stairs. Ferguson, who was returning fire through a second-floor window, was knocked to the floor. Rubble from the ceiling fell in on him. As the RUC men recovered from the blast there was another lull, and again the IRA called for those inside to surrender.

Kavanagh was considering a frontal assault into the barracks when the RUC started firing again. Realizing that reinforcements were probably on the way, Charlie Murphy recommended that they withdraw. It had been twenty minutes of intense battle. Volunteers were tiring and it showed; their fire had slowed and was less organized. Kavanagh ordered the column back together and as two groups they took off along either side of the road. They had not gone far when an RUC Land Rover with its lights off appeared. They considered an ambush but instead allowed it to pass unmolested.

Behind them they left a wrecked police station. An RUC officer later overestimated that forty IRA volunteers were involved in the attack. Broken glass and debris were scattered inside and outside of the building Walls were pitted with bullet holes. Broken planks and twisted iron were in front; piping and wiring hung from the roof. A first-floor ceiling “dangled to the floor.” The second floor was a mess. A priest was called for Constable Scally, who was taken by ambulance to Fermanagh County Hospital in Enniskillen. He died en route from shock and bleeding. An autopsy showed that bullet fragments had severed his spinal cord and lacerated his spleen. He had been engaged to be married.

After the RUC Land Rover had passed, the column moved south toward their County Fermanagh base near the border. As they made their way into the hills at the foot of Slieve Rushen Mountain, they saw warning flares going off in the sky. Because they had withdrawn quickly, they were safely beyond the British Army and RUC cordon. Several men were tired, and Murphy wanted to stop and rest. Kavanagh pressed on, and the column spread out. Snow began to fall and it got colder. The mountain’s iron ore deposits rendered their compasses useless and they got lost and wandered about. They were cold and exhausted, and someone produced a bottle of Advocaat, a liqueur. Ó Brádaigh, true to his Pioneer Badge, had always been an abstainer, but he was persuaded to take a few drinks for medicinal purposes. They went straight to his head and he felt he was walking on air, to the amusement of his comrades. Finally getting their bearings, the group made their way up and over Slieve Rushen, missing their base and ending up in the Ballyconnell district of County Cavan. As they came down the mountain, they could see Gardai behind them on the mountainside, searching for them. Kavanagh, exhausted, was left in a friendly house. The column split into groups and sought refuge in other houses in the general area. It was a hit-or-miss proposition, and several volunteers were lucky and escaped arrest. Kavanagh, who was not so lucky, was arrested. So were Ó Brádaigh and his group.

Rainsoaked and covered with dust, Ó Brádaigh and five others ducked into a house in the tiny village of Clinty, about a mile from Ballyconnell. Gardai surrounded the house, saw the men inside, and entered through the back door. When a superintendent asked who was in charge, Ó Brádaigh said that he was and instructed the others to provide only their names and addresses. They had dumped their weapons and were unarmed, but Ó Brádaigh had a haversack that contained ammunition, a practice genade, and a copy of Cronin’s Notes on Guerrilla Wafare. They were put into police cars and taken to Ballyconnell police station. On the way, he quietly tossed the ammunition out of the car’s window, but the police spotted this, retrieved the ammunition, and then went through the haversack.

It was in the house that they learned of Constable Scally’s death. The civil and religious authorities, north and south, viewed the killing as murder. At the coroner’s inquest on the death, an RUC Inspector stated that the attack had achieved nothing and that it personified, quoting Robert Burns, “Man’s inhumanity to man.” Ó Brádaigh and his fellow volunteers had a different view. Scally was a victim in a war of national liberation. It was nothing personal against Scally; Ó Brádaigh, after thinking that a “bastard" (later identified as Constable Ferguson) was trying to shoot him, immediately recognized that the man had every right to shoot back. The IRA were soldiers fighting against British colonial interests in Ireland; Scally, as a uniformed and armed member of the state’s militarized police, directly supported those interests. As soldiers, they knew that eventually they would kill someone, just as some of them might be killed. It was what they had been training for. It was never clear who fired the fatal shot (the Bren and the rifles used the same ammunition), and the raiders collectively shared responsibility. In 1991, Joe Jackson interviewed Ó Brádaigh for the magazine Hot Press. Jackson asked Ó Brádaigh if he knew who fired the shot that hit Scally. Ó Brádaigh replied, “I’d say everyone who took part in the attack shared responsibility, not just the man who shot the bullet. It can’t be blamed on anyone in particular.” Scally was the first fatality of the campaign.

At the police station, Ó Brádaigh requested that his initial interview, with Garda Superintendent Kelly, be in Irish. Instead, the relevant section of the Offenses Against the State Act was read to him in English. He put his fingers to his ears. Kelly then used Irish to ask him to account for his activities. Replying in Irish, he refused to answer. According to Ó Brádaigh, Kelly took him into a separate room and asked for the whereabouts of other members of the column. He offered to bring them in off the mountain and, in the rain and sleet, have them driven home. He also offered to drop charges related to the items in the haversack if Ó Brádaigh provided information on the IRA volunteers still at large. Ó Brádaigh refused. A Special Branch inspector, Philip McMahon, arrived and also spoke to him privately, asking him to reveal the whereabouts of the rest of the column. Again he refused. At about 830 in the evening the seven prisoners were taken from the police station, placed into two police cars, and transported to the Bridewell Detention Centre in Dublin.

While Ó Brádaigh and his group were being interrogated in Cavan, Sein Garland, commanding officer of the Patrick Pearse Column, received information on the Derrylin raid. His column, which included Sein Scott and a young volunteer from Cork, Diithi O’Connell, had been unsuccessful in their attempts to ambush an RUC patrol. Garland decided to attack the RUC’s Brookeborough Barracks, also in County Fermanagh. On New Year’s Day they seized a truck and drove to the barracks. Like the IRA at Derrylin, they were armed with gelignite mines, machine guns, and rifles. Unlike Derrylin, this raid did not go well. The mines did not go off and the RUC return fire found its mark. Several volunteers, including Garland, were shot. The IRA withdrew in the truck and crossed a mountain back over the border into County Monaghan. Two of the wounded, Seán South and Feargal O’Hanlon, were dying. They were left in a farm shed in County Fermanagh and local people were asked to call a priest and a doctor. The other volunteers abandoned the truck and dumped their arms but were arrested on the morning of January 2, 1957. The wounded were sent to hospitals; the healthy were sent to Mountjoy Prison in Dublin. South and O’Hanlon died in the barn and became legends.

In the popular imagination of Irish Nationalists, the tragedy of the raid at Brookeborough, where two IRA volunteers died, eclipsed the tragedy at Derrylin, where a member of the RUC died. South and O’Hanlon were immediately canonized as martyrs for the Republican cause. They were viewed as idealistic young men who died for something most Irish people wanted but were unwilling to sacrifice for. O’Hanlon, who was only 21 years old, was a prominent Irish-speaker and Gaelic footballer in Monaghan. South, who was eight years older, was from Limerick. He was known for his devotion to Catholicism and the Irish language. Each became the subject of a popular ballad: for South, “Sein South of Garryowen,” and for O’Hanlon, “The Patriot Game.” O’Hanlon was buried not far from where he died. South’s funeral procession, which traveled from Monaghan to Limerick via Dublin, affected thousands of people in the Twenty-Six Counties. In Dublin, the IRA staged a large rally with volunteers standing at attention beside the hearse. In Limerick, 50,000 people attended the ceremony.

The Derrylin prisoners-Kavanagh, Ó Brádaigh, Pat McGirl, Paddy Duffy, Joe Daly, Dermot Blake, and Leo Collins-spent New Year’s Day in solitary confinement in the Bridewell. The next day they appeared in Dublin District Court, dressed in a mix of military uniforms that included British Army battle dress, a British Army officer’s tunic, weatherproof jackets, and British Army and black berets. Each had a tricolor flash on his left sleeve. Because they were in uniform and under the command of a superior officer, they were prisoners of war under the IRA’S interpretation of the Geneva Convention. The Irish authorities treated them as criminals.

Late in the afternoon they appeared before Justice Michael Lennon and were charged under Section 52 of the Offenses Against the State Act with failing to account for their movements. It was the same Offenses Against the State Act that Matt Brady had protested in 1939 when it was first proposed. Detective Inspector John O’Flaherty of the Special Branch informed the justice of the charges. The justice, an old Sinn Ftiner and Irish Republican Brotherhood man, raised a technical issue. Under Irish law, Section 52 came into force via a public proclamation from the government. Lennon asked for proof that this had happened. O’Flaherty did not have evidence of a proclamation, and the justice dismissed the charges against all seven. (Justice Lennon subsequently resigned at the government’s request.) They were not immediately released but were returned to the Bridewell. Because he was unarmed and arrested by himself with no incriminating evidence, Kavanagh was later released. The others, who were implicated by the items found in Ó Brádaigh’s haversack, spent the night in the Bridewell. That same day, eight of the captured Brookeborough raiders appeared in another court and were remanded to Mountjoy.

On January 3rd, Ó Brádaigh, Pat McGirl, Joe Daly, and Dermot Blake were back in court, this time facing District Justice Reddin. Paddy Duffy and Leo Collins were sick and unable to attend. The prosecution was ready and offered evidence that the government had publicly proclaimed that the IRA was an unlawful organization and that the Offenses Against the State Act was in force. The group was then formally charged with five offenses: membership in an illegal organization, refusing to account for their movements on the evening of December 30 and the morning of December 31, possession of fourteen rounds of .303 ammunition, possession of a practice grenade, and possession of an incriminating document-Cronin’s Notes on Guerrilla Warfare. As they were IRA prisoners in a court that they did not recognize, the proceedings consisted of Detective Inspector O’Flaherty describing the respondents’ refusal to answer questions. When O’Flaherty read the charges to them, Ó Brádaigh responded in Irish: “Ni fheddfadhJios a bheith ag aon duine des na fedraibh eilefaoi a raibh I mo mha’la agus ni raibh aon bhaint acu Len a raibh i mo mhdla” [It would not be possible for any of the other men to know what was in my bag and they had no connection with anything that was in it]. When offered the chance to provide a statement, the others had responded with, “Nothing to say.” In response to the charge of failing to account for their movements, Ó Brádaigh replied, “Nil aon rud le rd agam” [I have nothing to say]. In court, when the justice asked if they had any questions for the inspector, none of them replied. When he finished presenting the evidence, Walter Carroll, of the chief state solicitor’s office, asked that the men be remanded in custody for another week.

Justice Reddin then asked the prisoners if they had anything to say. Ó Brádaigh spoke for them: “We have already been three days in solitary confinement, and on New Year’s Day we were not permitted to go to Mass. On behalf of the men I wish to make a protest in the strongest possible form against their treatment.” The prosecutor said he was surprised to learn this, but added, “I cannot make any comment.” Ó Brádaigh could: “We made several objections and were told there were no facilities for hearing Mass in the Bridewell.” He also complained that they were being held illegally. Under the Offenses Against the State Act they could only be held for forty-eight hours without being charged. “Our period of detention was up yesterday [January 2nd] at 4.30 p.m.,” he said. “We were brought into Court and the charge was dismissed. We were not allowed to leave the Bridewell until 12.30 this morning when we were again charged. It would appear to us that our detention on the third day is illegal.” O’Flaherty and Carroll countered that they had been charged within the 48-hour period. The justice accepted this and asked the prisoners if they objected to being held on remand for a week. Ó Brádaigh replied, “I have no objection to a remand, but we would prefer that it would not be in the Bridewell again in solitary confinement.” Informed by the prosecutor that the remand would be to Mountjoy, he replied, “Very good.” Justice Reddin then asked if any of them sought bail. Speaking for the group, he replied, “No sir.”

Prisons north and south were filling with Republicans. On January 8th, Irish police officers spotted Sein Cronin, Robert Russell, Noel Kavanagh, and Paddy Duffy-who had escaped from a hospital near the Bridewell-in a car outside Belturbet in County Cavan. They were arrested and sent to Mountjoy. On January 12th, 100 people were arrested in Belfast. That same day, Tomis Mac Curtiin addressed a large crowd at College Green in Dublin. He argued that the IRA did not threaten the Dublin government and that volunteers would not return the fire of the Irish Army. It did not help. The next day most of the IRA’S leadership, including Tony Magan, Larry Grogan, Charlie Murphy, and Tomis Mac Curtiin, were arrested; they too ended up in Mountjoy.

On Monday, January 14, 1957, the Derrylin raiders made their final court appearance, before Justice Fitzpatrick. They marched in and remained at attention. The justice informed them that they could be seated and Ó Brádaigh issued the order “Suzgi sios” [Sit down]. Informed that they had the right to a trial by jury, each replied, “I am not interested.” The prosecutor, Mr. Carroll, described their arrest, including Ó Brádaigh’s attempt to toss items out the car window. When Superintendent Kelly, one of the arresting officers, took the stand, Justice Fitzpatrick offered Ó Brádaigh the chance to question him. Ó Brádaigh began by asking Kelly if he wanted to speak in Irish or English. Kelly replied that it did not matter. The justice asked for an interpreter, stating, “I recognise your right to speak the Irish language, but I would like to have an interpreter as I do not know it.” Superintendent Kelly then said that he would prefer to have the questions in English, as he did not know enough Irish.

Ó Brádaigh proceeded in English. When he came to Kelly’s offer to drop the charges in exchange for information, Kelly denied that he had made such an offer:

Ó Brádaigh: “Do you remember having a private conversation with me in one of the rooms of the police barracks?”

Kelly: “Yes.”

Ó Brádaigh: “Do you remember showing me a tin with a number of rounds of ammunition?”

Kelly: “Yes.”

Ó Brádaigh: “Did you ask me to take responsibility for that ammunition?” Kelly: “No.”

Ó Brádaigh: “Did you promise me on that occasion there would be no charge in relation to those rounds contained in the tin?”

Kelly: “No, no, I did not give any promise at all of that.”

Ó Brádaigh: “Did you at the same time ask the whereabouts of other members of our party?”

Kelly: “Yes.”

Ó Brádaigh: “Did you press me hard as to where they were?” Kelly: “I do not know whether you could say I pressed you hard.”

Ó Brádaigh: “Did you ask me would I give my word of honour as to where they were?”

Kelly: “I did.”

Ó Brádaigh: “Do you remember taking me aside and promising that the men now in Court would be driven home?”

Kelly: “I did not give a definite promise at all.”

The judge, who was interested in the line of questioning, interjected with, “Did you give a promise of any sort?” Kelly replied, “No.” As Ó Brádaigh remembers it, Kelly “had the grace to blush when the Judge pressed him.” Ó Brádaigh, who was inexperienced at dealing with police officers, was shocked by the denial under oath.

Detective Inspector O’Flaherty also appeared as a witness. Ó Brádaigh used him to make political points. The Hungarian Revolution against the Soviet Union had begun in October 1956, and Imre Nagy had been appointed prime minister of Hungary. In November, Soviet troops attacked Budapest and Nagy fled. Janos Kadar formed a countergovernment with Soviet support. Ó Brádaigh asked O’Flaherty, “Would you agree that the Government of Northern Ireland has no more legitimacy than the Kadar regime in Hungary?” O’Flaherty replied: “I am afraid I could not express an opinion on that.” Ó Brádaigh persisted: “If the freedom fighters of Hungary were forced to cross the Austrian Border would they not have received better treatment than we did?” The Justice intervened, “You need not answer that question. It is not relevant.”

The state rested its case and the IRA prisoners were asked if they wanted to give evidence or call witnesses. They declined. Justice Fitzpatrick then found them guilty of the charges and imposed a sentence of six months in prison for each. Ó Brádaigh then asked for permission to address the court. The Justice stated, “The case is finished. I gave you an opportunity of giving evidence and calling witnesses and you said you did not wish to do so. I will listen to you but I will ask you not to make anything in the nature of a political speech.” Ó Brádaigh pleaded ignorance of court procedures and tried to make a political speech.

He was frustrated that the Irish authorities would repress the IRA but offer sympathy to movements outside of Ireland that also used physical force. In the 1930s, there had been widespread support among politicians for an Irish Brigade that went to Spain in support of Franco and fascism. In the 1950s, Soviet repression of the Hungarian rebellion had generated sympathy throughout the Western democracies for the Hungarian people and for Hungarian activists who used physical force against the Soviets. In Cyprus, British repression of EOKA (Ethnica Organosis Kyprion Agoniston; National Organization of Cypriot Fighters) activities and the general Greek population had contributed to anti-British sentiment in Ireland and official concern from Irish politicians. Ó Brádaigh tried to point out this inconsistency: “I have little to say other than that, as members of the Irish Resistance Movement against British occupation in Ireland, we resent it very much indeed being arrested by fellow Irishmen while fighting against British occupation in Ireland. Had we banded ourselves together to go to fight for Hungary or Cyprus or formed an Irish Brigade to go to Spain-.” Justice Fitzpatrick cut him off in mid-sentence, “I am sorry. This is a speech on matters which you might regard as national or international or, indeed, embracing the whole world. But that is outside my jurisdiction. I have already dealt with the case and I do not propose to listen further.” This ended the case. In response to Ó Brádaigh’s orders, which were given in Irish, the prisoners marched out of the dock. They were sent back to Mountjoy, where they were soon joined by those sentenced for their participation in the Brookeborough raid. They had also received a six months’ sentence.

The campaign, at least from the IRA’S perspective, had been going well. In Sein Cronin’s Dublin flat, the Gardai had found an IRA document that was probably written in early January and titled, “Outline of Operations to Date.” It stated:

From the Fermanagh experience we can prove that where guerrillas are active and aggressive the enemy becomes scared and confused. If we had Fermanagh activities all over we would be in a tremendously strong position in the Six Counties. We still hold the initiative in all areas and our limited supplies in most cases remain intact. We got more gelignite than we ever hoped for.

In early January, IRA columns had been reorganized into battle teams, which were effective, but there was room for still more improvement:

Among the lessons we have learned are: The training of our men is still very spotty. The battle teams are only beginning to work in Fermanagh. Men are quite close to panic during the withdrawal phase. There is lack of battle discipline. Too many shout orders. Too many act without an order at all. This can cause loss of lives. The way to cure this is to make the column a well-moulded fighting team of battle teams, sections-all integrated in the column, every man given a job in the attack. No firing without an order.

By the end of January 1957, however, almost all of the IRA leadership was in Mountjoy, including Tony Magan, Tomis Mac Curtiin, Larry Grogan, Charlie Murphy, Sein Cronin, Robert Russell, and Ruairí Ó Bddsigh. Paddy Doyle was in Crumlin Road Prison, Belfast. This hurt the campaign, which was in the hands of a temporary IRA Army Council that included Tomis Ó Dubhghaill and Paddy McLogan as an observer.

Ó Brádaigh found Mountjoy to be “all right,” although the food left a great deal to be desired. Conditions were not exceptionally harsh and prisoners were not abused by the warders. The negative aspects of being in prison are numerous: loss of freedom, loss of personal space, and so forth. Perhaps the only benefit is that it brings together Republicans from throughout Ireland and allows them the chance to build camaraderie. In 1916, the British had placed a large number of rebels in the same internment camp in Wales, Frongoch. Out of that camp the Republican Movement rebuilt itself in 1917. Forty years later, the benefits of bringing together people in Mountjoy were not as striking as in 1916, but significant relationships were formed there that continue to influence Ruairí Ó Brádaigh.

In prison, IRA members lose their rank and the prisoners elect their own commanding officer. An IRA chief of staff on the outside becomes a regular volunteer on the inside. This allows for continuity of leadership in the prison and for smoother relations. If an IRA officer were to enter a prison and attempt to take over and issue commands, it might breed confusion and factions. The IRA’S leadership did not assume the leadership in Mountjoy; Diithi O’Connell had been elected commanding officer by the first set of prisoners and he remained so.

Many of those in the leadership, including Mac Curtiin, Tony Magan, and Larry Grogan, were in prison in the 1940s; Grogan had been in Mountjoy in the 1920s. Ó Brádaigh remembers them taking to prison like “ducks to water.” He gravitated toward the senior people. Pragmatically, he figured he could draw on their experiences to make the time pass more easily. The younger people in general tended to follow the lead of the senior people. He also saw an opportunity to add to the record of Irish history; he saw the senior people as actors in events that had often gone unrecorded, and he did not want this lost to posterity. Today, some of their stories appear in his “50 Years Ago" column in Republican Sinn Fdin’s paper, SAOIRSE. His interest in history was such that he even talked to some of the senior warders who had witnessed the executions and later exhumations of people such as Charlie Kerins and Paddy McGrath.

Tomb Mac Curtiin was particularly interesting. Mac Curtiin had been within hours of his execution in 1940. He saw what was to be his coffin brought into the prison and he knew that the hangman, who had been imported from England, was on site. His cell in 1940 was the prisoners’ recreation room in 1957. The execution chamber was at the end of the wing. According to Ó Brhdaigh, Mac Curtiin was convinced that upon his execution he would go “straight up to heaven.” He had settled his affairs, was prepared to die, and did not expect to be reprieved. When the reprieve came the night before the scheduled execution, it caught him by surprise. The next morning, he told Ó Brádaigh, “I just simply didn’t know what to be doing.” Mac Curtiin was not confused for long. After he was moved from the cell for condemned prisoners, he began organizing the other prisoners. The authorities transferred him to Port Laoise Prison in County Laois. There he refused to wear a prison uniform or do prison work and was laced in solitary confinement (Ó Brádaigh refers to him today as the first “blanketman"). In solitary, Mac Curtiin searched for ways to break the monotony. When a mouse joined him in the cell, he tried to train it to run up one arm and down the other. On the third attempt, it bit him.

Among the younger prisoners that Ó Brádaigh became close to was David O’Connell. Formally, O’Connell went by the Irish version of his name, DGthi. Informally, he was “Dave.” Tall, thin, and with a Cork accent, he was only 18 years old. He looked to have a good future as a cabinetmaker; in 1955, he had been awarded first prize in Ireland and Britain in his apprenticeship examination and had received a gold medal. Like Ó Brádaigh and so many of their contemporaries, he was from a Republican background; an uncle was bayoneted to death by British soldiers in 1921. The 1955 local elections in the Twenty-Six Counties had caught O’Connell’s attention and he had sought out the Republican Movement. He was interviewed for IRA membership by Mick McCarthy. McCarthy remembers that O’Connell was concerned that he would not be eligible for membership because he had briefly joined the Irish territorial army, the Fórsa Cosanta htiliil (FCA, “Local Defense Force"). He feared that this implicit recognition of the state would make him unacceptable. It was not a serious issue, and O’Connell was recruited into the IRA. O’Connell’s concern is indicative of his intensity and of how careful Republicans were not to recognize the state. He was so intense that in prison he was referred to as “Mise ire,” or “I am Ireland.” Ó Brádaigh first met O’Connell on St. Stephen’s Day, 1956. Ó Brádaigh, as second in command of the Teeling Column, transferred some men to O’Connell, who was second in command of the Pearse Column. In Mountjoy, they developed a friendship that lasted until O’Connell’s death in 1991.

While in prison Ó Brádaigh was visited regularly by his family. For many families, it would be a disaster to have a son and brother arrested for his involvement in the killing of a police officer. The Ó Brádaighs, who knew that Ruairí was involved in the campaign, were not surprised that he ended up being arrested. It was a likely outcome of being an activist. As far as they were concerned, Scally was a regrettable casualty of war. They did not rejoice at the death but neither were they repulsed by it. The family knew well the risks of involvement in the IRA; Matt Brady had been shot by the RIC, the RUC’s predecessors. Seán Ó Brádaigh’s reaction to Ruairí’s arrest was to be annoyed with the Irish government-in trying to seal the border and in arresting IRA personnel, they were collaborating with the British government. For many people, Republican and Irish Nationalist, the killings of South and O’Hanlon put the killing of Scally into perspective; both “sides" were suffering in a military campaign. The huge funerals for South and O’Hanlon were a source of pride in the cause.

The family visited Ruairí whenever they could. His mother May traveled by train from Longford to Dublin. On occasion, she was joined by Ruairí’s sister, Mary, who had returned to Ireland in 1955 to study for an MA in English (focusing on John Millington Synge) at University College Dublin. There she had met James Delaney, who was also pursuing an MA. They had married and temporarily moved in with her mother. Under the 1937 Irish Constitution, as a married woman, Mary was ineligible for employment by the state; they were planning a family. Visiting Mountjoy was easiest for Sein, who had followed Mary and Ruairí on to University College Dublin and, like his siblings, was studying to become a teacher. Another regular visitor was Patsy O’Connor, a teacher at Roscommon Vocational School. Patsy, a graduate of University College Galway, had joined the staff in 1953, a year before Ruairí. Her degree was also in commerce; she taught bookkeeping, business methods, shorthand, and typing. They had much in common, including a love of books. She had attended an all-Irish secondary school, and although she was not fluent, she shared his interest in the language. As Patsy describes it, “We could talk about anything. And we still do.” Although they were not engaged, they had an understanding that they would be married. Patsy would take the bus from Roscommon to Longford and then ride to Dublin with May.

Assorted aunts, uncles, and cousins also visited, including his Uncle Eugene’s family, which was living in Dublin. The families were close, and the Ó BrPdaighs had often visited the Caffreys in Donegal. On one of these visits, when Ruairí was 10, he had worn a blazer with several pockets. The pockets fascinated his 2-year-old cousin Deirdre, who went through each one of them. Ruairí, a very serious youngster, told her mother that she should teach the child to not go through men’s pockets or else when she grew up she would go to jail. On her first visit to Mountjoy, Deirdre, now 16, bounced into the visitor’s box, looked at Ruairí, and asked, “Who went to jail?” It became a standing inside joke between the two of them.

Life and politics go on outside of prison. So do IRA campaigns. Republican prisoners follow external political events as closely as they can. Visits from family and friends are important sources of information. On occasion, IRA prisoners become central players in external political events; in late January 1957, Sein Mac Bride, TD, put forward a motion of no confidence in the government, primarily because of Costello’s actions against the IRA. The government fell and Costello called an election for March 5th.

Republicans are always interested in elections, even when they do not participate in them. March 1957 was great timing for participation. The campaign had made Northern Ireland an important issue in 26county politics. The deaths of O’Hanlon and South had generated enormous sympathy for the cause, and the movement had several promising candidates to offer the public, including Feargal O’Hanlon’s brother, Éighneachán. Others included Paddy Mulcahy, a city councilor in Limerick; John Joe McGirl, the highly respected Leitrim publican and a prisoner in Mountjoy; and Ruairí Ó Brádaigh. At the encouragement of the Ó Brádaigh family, Ruairí was selected as Sinn Ftin’s candidate at a Longford-Westmeath constituency convention. In Mountjoy, and with some hints from Tony Magan, he wrote his first election address. It was later adopted as Sinn Ftin’s general manifesto for the election. He pledged to work for the unity and independence of Ireland and to take a seat only in a 32-county All-Ireland Parliament.

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh was an ideal candidate for a seat in LongfordWestmeath. Longford had a history of electing Republican prisoners; in 1917, Joe McGuinness won in South Longford. Ó Brádaigh’s campaign adopted McGuinness’s slogan: “Put him in to get him out.” Ballads were composed, including one that began, “In Bridewell court one Monday morning, In this land the State calls Free.” The Ó Brádaigh name was prominent throughout the constituency. Older people remembered Matt Brady, a county councilor from 1934 to 1942 and a member of the Mullingar Mental Hospital Committee. For thirty-six years, May Brady Twohig had been the secretary of the Longford Board of Health, certifying birth, death, and marriage records. Mary Delaney was Ruairí’s election agent, and May and Sein actively worked on the campaign.

Republican Longford rose to the occasion. People who for years had rejected any form of constitutional participation were mobilized. Sein F. Lynch’s mother-in-law, a staunch Republican, voted for Ó Brádaigh; it was the first time she had voted in a general election since the 1920s. The family’s efforts were not without their humorous side. Calling at a house one day, Sein asked the occupant if he would be willing to work for Ruairí’s campaign. The man replied, “Yes, of course I will work for your brother. I voted for Joe McGuinness in 1918 [to re-elect McGuinness], I voted for de Valera in 1932, and I voted for SeAn Mac Bride in 1948. And of course I will vote for your brother now.” In each case, he had voted for the most “Republican" candidate available. SeAn kept to himself the view that de Valera had gone on to arrest and execute Republicans and that Mac Bride had entered Leinster House.

Sinn FCin’s intervention was an incredible success. With a total of nineteen candidates, the Party won 65,000 first-preference votes and elected four candidates: Éighneachhn O’Hanlon in Monaghan; John Joe Rice, a Republican veteran of the 1920s, in South Kerry; John Joe McGirl in Sligo-Leitrim; and Ruairí Ó Brádaigh in Longford-Westmeath. McGirl topped the poll in Sligo-Leitrim. In Longford, SeAn Mac Eoin topped the poll, as usual. But Ruairí Ó Brádaigh finished second with more than 5,500 first-preference votes and was elected. In the complicated system of vote transfers and multiple seats in one constituency, Ó Brádaigh replaced a Fianna Fail incumbent. It was an amazing result for a party that endorsed a paramilitary campaign and rejected participation in Parliament.

The day after the count over 1,000 people attended a rally in Longford in support of their jailed abstentionist Teachta DAla. A band played marches and the town courthouse was decorated with Irish flags and a Sinn FCin banner. Thomas Higgins of Longford Sinn FCin read a letter from Ó Brádaigh to the crowd. He thanked his supporters for their work and then drew a parallel to the 1917 election: “Longford and Westmeath have matched their achievement of 40 years ago, and have written yet another page in the history of our struggle for unity and independence.” He also looked to the future, “If 1957 has been another 1917, then let us in God’s name look forward to another 1918, to the day in the near future, when the All-Ireland Parliament, pledged to legislate for the whole 32 Counties will be re-assembled.” Another speaker was Seán Ó Brádaigh, who stated, “We want to end the corruption, graft and hypocrisy that has been going on for the past 35 years.” The rally ended with the singing of “A Nation Once Again" and the national anthem.

From a revolutionary Republican point of view, the election was a watershed, Sinn FCin’s best showing in the Twenty-Six Counties since 1927. Combined with the Mid-Ulster and Fermanagh-South Tyrone results from 1955, Sinn FCin had elected six deputies to an All-Ireland Parliament. From the perspective of constitutional politics, Sinn FCin’s success was less dramatic. The party had elected four of 147 members of Leinster House. And because they were abstentionists, those four people would have no voice in the formation of the new government. Neither would Seán Mac Bride, who lost his seat. The big winner was Fianna Fáil, which elected seventy-eight Teachtai DAla and formed yet another government with am on de Valera as Taoiseach. De Valera, the most successful Irish politician of the twentieth century, was interviewed soon after the election. The most important issue for him was the Irish economy, which was forcing people to emigrate-"Unemployment is the one thing I am thinking at the moment.” He was also asked, ’Rs an old I.R.A. fighter yourself, what is your present view towards the revival of this extreme national movement?” His reply brought no comfort to Sinn FCin and the IRA, “As far as this part of the island is concerned, we have here a democratic system completely free and you cannot have two armed forces obviously.”

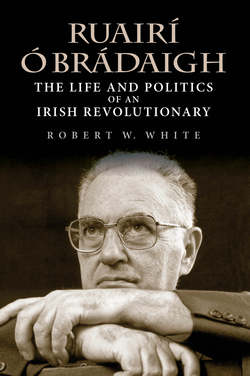

Mary Ó Brádaigh Delaney at a Sinn Féin rally in support of her brother, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, TD, Longford, 1957. Ó Brádaigh family collection.