Читать книгу Ruairí Ó Brádaigh - Robert W. White - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Off to College and into Sinn FLin and the IRA

1950–1954

IN THE FALL OF 1950 Rory Brady left Longford for Dublin, where he went into digs with a friend of his Aunt Bertha, who set up the arrangement. University College Dublin’s campus was located a bicycle ride away, just up from St. Stephen’s Green. It was a time for several key events in his life. He adopted the Irish form of his name, changing from Rory Brady to Ruairí Ó Brádaigh (his younger brother had already changed his name and was known at St. Mel’s, class of 1955, as Sein Ó Brhdaigh). Dublin, Ireland’s capital, was the site of the headquarters of Sinn Ftin, which he joined. The first Republican event in Dublin he attended was a céili (an evening of Irish dancing) that was held in a hall in Parnell Square in honor of Hugh McAteer, Liam Burke, and Jimmy Steele, three prominent IRA men who had recently been released from prison in Belfast and were among the last of thousands of prisoners in the 1940s.

Sinn Féin has a hierarchical structure that begins at the lowest level with a cumann (club), which is usually named after a deceased activist. Ó Brádaigh joined the Paddy McGrath Cumann, named for the man whose reburial he read about in 1948. Each cumann has five to ten members and meets weekly. Cumainn send two delegates to the Sinn FCin Ard Fheis (annual conference), which is usually held in Dublin. At the Ard Fheis, the delegates elect the Sinn Féin Officer Board and the party’s Ard Chomhairle (Executive). Even though he was one of its newest members, Ó Bddaigh attended the Ard Fheis, which was held at the Sinn Féin head office at 9 Parnell Square, as a delegate. On November 19, 1950, about seventy delegates took their seats in a large front room on the first floor of the building.

He saw several prominent activists firsthand at what was an historic Ard Fheis. Margaret Buckley, the party’s president since 1937, stepped down, although she remained on the Ard Chomhairle. She had been a member of the Irish Women Workers’ Union and a judge in the revolutionary Sinn Féin courts and was imprisoned in Mountjoy and Kilmainham jails for her Republican efforts. In 1938, she published her jail journal, The Jangle of the Keys. Because of his mother’s background, Ó Brádaigh found Buckley especially interesting. Paddy McLogan succeeded her as president. McLogan, Tony Magan, and Tomis Mac Curtiin were the “three Macs" who dominated the IRA and Sinn Féin in the early 1950s. McLogan’s assumption of the Sinn Féin presidency was in fact the result of a friendly coup organized by the IRA. As they picked up the pieces in the late 1940s, the IRA’S leadership realized that they needed a public political vehicle to complement their clandestine activities. After twenty years of estrangement, they adopted Sinn Féin as that vehicle. McLogan, Magan, and Mac Curtiin, and the IRA in general, were not interested in recognizing Leinster House or Stormont, and Sinn Ftin’s policy of abstentionism from those bodies and Westminster was consistent with IRA policy. IRA volunteers were “infiltrated" into Sinn Ftin; Sinn Féin welcomed them and became the political wing of the Irish Republican Movement.

Magan, McLogan, and Mac Curtiin were hard men who were dedicated to the cause. Each had impeccable credentials. McLogan was born in 1899 in South Armagh, in what became the Six Counties of Northern Ireland. He was on hunger strike at Mountjoy Prison with Thomas Ashe in 1917 and was later held under an assumed name in Belfast Jail while the police searched for him outside on a charge of murder. In the 1940s, he was interned in the Curragh Military Camp. He made his living as a publican in Port Laoise. McLogan is described as “placid in temperament and ice cold in contention, but easy to trust" and “the Father of Republicanism, the austerêlotter from a previous generation.” Deeply religious, he had met his wife on a pilgrimage to Lourdes. Tony Magan, the IRA’S chief of staff, was in his late 30s. He was from County Meath and had joined the IRA in the 1930s; he was also interned in the Curragh. A bachelor and devout Catholic, he is described by J. Bowyer Bell as “a hard man, tightly disciplined, and utterly painstaking.” Tomis Mac Curtiin, the youngest of the three, was in his mid-30s. He was the son of Tomis Mac Curtiin, the Sinn Féin mayor of Cork who was murdered in 1920, allegedly by members of the Royal Irish Constabulary. The younger Mac Curtiin was a member of the IRA’S Army Council and, in the late 1950s, of Sinn FCin’s Ard Chomhairle. He was on the 1940 hunger strike at Mountjoy. After the strike was called off, he was sentenced to be hanged for shooting dead a Special Branch detective. Because he was the son of a Republican martyr, he was given a last-minute reprieve and was transferred to Port Laoise Prison, in County Laois. In Port Laoise, he and his fellow prisoners refused to wear prison uniforms or follow the routine. They spent years in solitary confinement, naked, wearing only blankets. Their resistance culminated in the death, by a hunger and thirst strike, of Sedn McCaughey in 1946.

Two of the three Macs and other hard-liners who helped reorganize the IRA were not universally loved, at least not by their comrades in the Curragh. Uinseann Mac Eoin’s The IRA in the Twilight Years: 1923–1948 offers interviews with people interned with Magan and McLogan. Life in the camp was rough, and because they were internees-they were never charged with a crime-there was no release date in sight. Fianna Fdil exacerbated the situation by offering parole to prisoners who recognized the state and pledged to forgo future participation in the Republican Movement. Some prisoners accepted the offer. The camp split over the best approach: take a hard line and refuse compromise with the authorities versus go softly and get through it. Magan and McLogan were with the hard-liners. Depending upon one’s perspective, they were part of a group of disciplined orthodox soldiers or they were autocratic martinets. When the division came, the hard-liners made their choice and stuck with it. An ex-internee who was on the other side of the divide recalls saying hello to Magan. “F off" was the reply. Another ex-internee describes Paddy McLogan as “a gand man, but if Paddy ever went to heaven he would cause trouble there; it was in his nature to cause trouble.” Yet because of their steadfast position, people such as Magan and McLogan kept the movement alive after the 1940s campaign. Their convictions got them through the Curragh; their convictions helped them reorganize the IRA and Sinn Ftin. To young recruits such as Ó Brádaigh, the three Macs provided an example of how to sustain and lead the Republican Movement.

The IRA’S headquarters were also in Dublin. As he continued his studies and attended Sinn FCin meetings, Ó Brádaigh sought membership in that organization. He figured out who in Sinn FCin was also in the IRA and mentioned that he wanted to join. The next time he met the person, he asked “Did you do anything about that?” To an eager recruit, the process was slow. About six months after joining Sinn Ftin, he was admitted to a recruits class that had five or six other potential IRA members. The class was directed by Michedl “Pasha" Ó Donnabhdin (Michael O’Donovan), a staff member of the Dublin unit. His lectures covered things such as the Constitution of the IRA, the Army’s general orders, and Irish and Irish Republican history. His job was to separate the reliable from the unreliable. He reported on who was ready to move from recruit to volunteer and who was not. Some never moved out of recruits classes. Ó Brádaigh, who was courteous, well-educated, and obviously motivated, quickly moved from recruit to IRA volunteer. He formally pledged the declaration (word of honor) to the Irish Republican Army in a ceremony held at 44 Parnell Square in Dublin; the building has been in Republican hands for decades.

Ó Brádaigh was fairly typical of IRA recruits at this time. He was in his late teens and he was the child of activists from the 1916–1923 period. The fact that he was a second-generation Republican in and of itself probably did not influence his admittance to the IRA. A recruiting officer might find a parent’s activities interesting, but recruiting officers are most interested in the merits of the recruit. Yet the Republican background of someone like him would have been so self-evident that his recruitment into the IRA was natural. According to senior Republicans at the time, Ó Brádaigh’s background “was written all over him.” He describes himself as “ready made”; it was evident to senior Republicans. If necessary, informal background checks were readily available. After joining the IRA, Ó Brádaigh for a time reported directly to Tony Magan as he sought to organize a unit in Longford. He was amazed at how much Magan knew about Longford. In the early 1950s, the Republican Movement was not very large, but its networks connected people throughout the country. Ó Brádaigh later discovered that Magan’s sisters lived in Longford. Through them, Magan knew what was happening there. He also knew of Matt Brady and May Brady Twohig; one of his sisters had been captain of St. Ita’s camogie team. These connections probably did not significantly influence Ó Brádaigh’s recruitment into the IRA. If he had been found unreliable, he would not have been accepted. Being from good stock was a bonus, but it was not essential.

In joining the IRA, the young recruits were not joining a country club or fraternal organization. They were joining a guerrilla army that was planning for war. In this they were not unique to Ireland. From the late 1940s through the 1950s, there were a number of active guerrilla campaigns throughout the world in places such as Aden, Algeria, Cuba, Cyprus, Kenya, Malaya, Palestine, and Vietnam. On July 26, 1953, Castro began the military campaign that resulted in his seizing control of Cuba on January 1, 1959. In Vietnam, Dien Bien Phu fell in May 1954, marking the end of French control in Vietnam. The guerrillas involved in these events were inspired by nationalism and were given the opportunity for campaigns by the decline of the colonial powers after World War 11. The 1960s would be the decade of student protest, but the 1950s was the decade of the guerrilla. Irish Republicans were aware of other guerrilla wars, in part because many of them, including those in Cyprus and Kenya, were directed against British forces. Many of the volunteers viewed 1916 as the first of the assaults against the British empire in the twentieth century. Colonialism appeared to be dying, and it appeared that other nations had passed by the Irish. The young volunteers believed it was their job to finish the Irish struggle for independence.

Combining his studies with his Republican activities, Ó Brádaigh soon became a recruiting officer for the IRA in Dublin and in Longford. On weekends and holidays he took the train, hopped a bus, or hitched a ride home and began reorganizing the Longford IRA; one ride was given by Sein Mac Eoin, who described Matt Brady’s activities to him. Organizing Longford required effort. The Free State had killed key people such as Barney Casey and Richard Goss, constitutional politics had attracted others, and the rest were too old and too tired. Ó Brádaigh began by taking part in Longford’s Easter Commemorations. At Easter 1951, the commemoration was at Killoe Cemetery, the burial site of Barney Casey. A parade, headed by the Drumlish Brass Band, marched to the cemetery. Casey’s family was there; Matt Casey was to become a fixture at Longford Easter commemorations, leading the way, bearing the Irish flag. Among those in attendance at this and subsequent commemorations were people from the previous generation, including May Brady Twohig, Hubert Wilson, Pat and Maggie Healy, and Sein F. Lynch, who was still on the County Council as an Independent Republican, and younger people, including Sein and Mary Ó Brádaigh and SeAn F. Lynch’s son, also named Sein.

There is a routine to Easter commemorations: the 1916 Proclamation and the IRKS Easter message are read to the crowd, as is the County Roll of Honour, a list of names of Longford’s soldiers who have died in the fight for Irish independence. A decade of the rosary is recited in Irish; The Last Post, Taps, and Reveille are sounded by a bugler; and wreaths are laid on behalf of relatives and various organizations, such as Sinn Féin or Óglaigh na Éireann (the IRA’S Irish name). One person usually presides over the ceremonies and introduces the keynote speaker, who is usually the most prominent Republican available. At Easter 1951 in Longford, the main oration was given by Michael Traynor of Belfast and later of Dublin Sinn Ftin. Traynor appealed to the local crowd by outlining the circumstances of Barney Casey’s death and linking his death with the larger Irish Republican cause: “It was because Barney Casey was a Republican and a Separatist that he was arrested and interned in the Curragh in 1940, and because he was in the Curragh on that morning of December lbth, 1940, he was brutally shot for being faithful to the people of Ireland. Long may his memory and his ideals live in the hearts of his countrymen.” The 1952 commemoration attracted a larger crowd. Hubert Wilson presided and Hugh McCormack of Dublin delivered the oration. He linked the honored Republican dead to the current Republican goals: “We should remember that it was not for a sham republic in a partitioned and anglicised Ireland that Sedn Connolly, Tommy Kelleher and Barney Casey died; and unless we are blind to the lessons of history we will find that the method which they adopted-physical force-is the only way to make England withdraw her occupation forces from our country.” He also looked to the future: “We must endeavour to build anew the national movement, which led the people to the verge of freedom in the years 1916–21 until it was betrayed by weakness and treachery at the top.”

Ó Brádaigh helped organize the 1953 commemoration in Ballymacormack and in 1954 he presided at the event at the memorial cross in Drumlish for Thomas Kelleher. The oration was delivered by Tom Doyle, who was serving as president of Sinn FCin for a brief period-McLogan returned to the post soon after this. In his remarks, Doyle reminded the audience that the “objective of those we commemorate has not yet been achieved.” He continued: “One fact we must keep constantly before usthe fact that British forces of occupation still hold six of our Irish counties against the will of the Irish people and by holding those six counties they dominate and control the life of the whole thirty-two.” He finished with an appeal to action: “Let us get rid of the invader out of every last inch of our territory-then and only then can we celebrate with a full heartthen and only then can we say that we have truly honoured our glorious dead.” Easter commemorations gave Ó Brádaigh an opportunity to recruit for the Longford IRA. He read the IRA’S Easter statement every year. Potential recruits could approach him and indicate that they were interested in more than Sinn FCin. Ó Brádaigh would then check the person’s background, a relatively easy task in a small county such as Longford. A prime resource was senior people, including Hubert Wilson and Sedn F. Lynch. Like Pasha Ó DonnabhGn, Ó Brádaigh’s job was to separate the reliable from the unreliable.

Ó Brádaigh was first a section leader of the Longford unit of the IRA. The section was attached to the Leitrim IRA, which was under the command of John Joe McGirl. Although it was only a nominal attachmentthey only met once or twice a year-it was significant. McGirl, who was about ten years older than Ó Brádaigh, was rebuilding the IRA in the area. He was reasonable and, more important, very enthusiastic. After two years, this arrangement was dropped and the small five-member Longford unit of the IRA became independent, with Ó Brádaigh as commanding officer reporting directly to Tony Magan. A perquisite of an independent unit is that it may send a delegate to the IRA’s annual convention. As an elected delegate, Ó Brádaigh attended the IRA’s 1953 convention. Aside from providing opportunities to participate in decision making and learn policy firsthand, conventions also bring together Republicans from throughout Ireland. One of the other delegates was Joe Cahill from Belfast. Cahill, in his early 30s, was one of six people arrested in 1942 and charged with the death of a Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC; reformed for Northern Ireland from the Royal Irish Constabulary). Five of the sentences were commuted. Nineteen-year-old Tom Williams, the commanding officer of the unit that killed the constable, accepted responsibility for the action, and even though he did not fire the fatal shot, he was hanged in prison in Belfast. Cahill was among the last of the 1940s IRA people to be released. He was to become a key figure in the Republican Movement in the 1970s.

Attending the convention gave Ó Brádaigh the opportunity to see at first hand how the IRA worked. Although it is a clandestine organization, the IRA has a structure to govern its members. The twelve-member IRA Executive calls the conventions, and this is an important source of its power. In calling a convention, the Executive sets in motion the process of creating a new IRA leadership. The convention is the IRA’s supreme authority, and it is here that delegates debate policies, tactics, strategies, motions, and so forth. The convention delegates directly elect the IRA Executive, which remains in place until the next convention. If someone is arrested or leaves for another reason, a new member is asked to join, or “co-opted,” onto the Executive until the next convention. The chair of the IRA convention convenes the Executive’s first meeting; if that person has not been voted onto the Executive, he or she retires. The Executive elects its own chair and secretary.

The IRA Executive then elects the seven-member Army Council, the size of which is derived from the number of people who signed the Proclamation of the Irish Republic in 1916. The Army Council appoints a chief of staff, who subsequently appoints a staff: adjutant general, quartermaster general, director of intelligence, and so forth. These staff appointments are ratified by the Army Council. Because the Army Council cannot be in continuous session, it lays down lines of policy for the chief of staff to carry out. In that way the chief of staff is answerable to the Army Council, which in turn is derived from the Executive. The Army Council generally meets on a monthly basis. Unless there are leaks or they participate in the process, volunteers do not know who is on the Executive, the Army Council, or the chief of staff. In his dealings with Magan, 6 Bddaigh knew that Magan was a member of general headquarters staff, but he did not know he was chief of staff until later.

As commanding officer of the Longford unit, O Brhdaigh’s primary activity was training people in weapons and explosives. The unit possessed a number of weapons, including a revolver, a pistol, a rifle, and a Thompson submachine gun. Gelignite detonators and fuses were also available. If they lacked particular equipment, loans were arranged from other units. The training goal was to make people familiar with all aspects of the arsenal. They met weekly. On occasion, more-intensive training camps, involving weekend overnights, were organized. For each situation, Ó Brádaigh began by arranging a secure area and the transportation of weaponry. Firing practice was often undertaken in County Leitrim, one of Ireland’s most underdeveloped areas. The unit also practiced advanced fieldcraft: battle techniques, ambushes, and attacking barracks. At some of the camps, the director of training, Gerry McCarthy, and a training officer, perhaps Charlie Murphy, Magan’s adjutant general, came down from Dublin and offered expertise. Ó Brádaigh was aided in this activity by his mother (who probably knew what he was doing) and the design of Silchester. May, who was widowed again-Patrick Twohig had passed away in March 1951 and was buried next to Matt Brady-loaned him her Model Y automobile. The hedges surrounding her home presented a cover such that he could walk out the back door with a rifle and head off down the lane.

Although Ó Brádaigh was devoted to the IRA-he traveled home on weekends so he could run training exercises-he found time for other activities. He was an avid attendee at ckilis organized by Republicans and non-Republicans. He was also active in extracurricular activities at University College Dublin. He has fond memories of the college boxing club, which met during the week. The gym was in a part of the university’s buildings that backed up to Irish government buildings. The students used to joke about tunneling through and setting off explosives. There were no showers, and they would clean off by dipping towels in a water bucket. One articular boxer, a flyweight from Belfast, would stand in the bucket, splash himself clean, and then announce that the bucket was available for the next person to wash his face. Ó Brádaigh and the others learned quickly to get to the bucket before the flyweight.

Irish literature and economic and industrial history were his favorite courses. His mother encouraged his studies in the field of commerce, which included accounting, organization, and business statistics. He also continued his study of the Irish language. Ó Brádaigh was starting to consider teaching as a profession when he attended an intensive course in the summer of 1952 at the Galway Gaeltacht, which was designed for people with college degrees who wanted a qualification in teaching Irish. As a training officer for the IRA, he had experience with addressing a group of people, commanding their attention, and running them through drills. The Irish instructors, who were unaware of his clandestine activities, thought he was a natural teacher and told him so. It was a key point in his academic career, and when he returned home he told his mother that he would seek a career as a teacher. His sister Mary, who had graduated from University College Dublin in 1951, had already made the same choice. Thus, in the spring of 1954, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh graduated from University College Dublin and received a degree in commerce and certification to teach that subject and the Irish language.

Like most college graduates, he applied for jobs “all around the place.” He received two offers, one from a school in Athlone and the other from Roscommon Vocational School. He chose the job in Roscommon because it was closer to Longford than Athlone and the bus service suited his needs. He wanted to be close to his twice-widowed mother and to stay involved with the Longford IRA. He moved home and, starting in the fall of 1954, took a bus to Roscommon, spending the week there. By this time, Sein was attending St. Mel’s as a day pupil. Because jobs were scarce, Mary was teaching in a primary school in Birmingham, England. Longford, which is in the province of Leinster, is lush with trees and vegetation, like much of the Irish midlands. Roscommon, only twenty miles away, is in the province of Connacht and is on the edge of the west of Ireland. From Roscommon to the Atlantic, trees and vegetation give way to hills and rocks, small sheep farms and stone walls, and fewer and fewer people.

The IRA leadership, which was apprised of Ó Brádaigh’s career plans, put him in touch with Tommy McDermott, who had been in the IRA in London when Terence MacSwiney died on a hunger strike in Brixton Prison in 1920. At the age of 18, McDermott had marched in MacSwiney’s funeral in London. He initially took the Treaty side in the Civil War, but when the executions started, MacDermott took his rifle and deserted to the anti-Treaty side. Never married, he was interned in the Curragh in the 1940s. Ó Brádaigh viewed McDermott as a lodestone, a role model who attracted the next generation of Republicans. According to Ó Brádaigh, he was a person who “went through it all, took all the hard knocks, and in good times and in bad he didn’t change his views or his principles to suit the tide of the time.” People such as McDermott stood out and “immediately attracted all the disenchanted.” They were very important for the maintenance of the IRA in lean times.

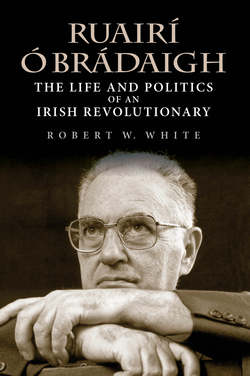

Ruairí Ó BrMaigh on graduating from University College Dublin, 1954. This photo accompanied several articles that appeared in the United Irishman of the 1950s. Ó Brádaigh family collection.

McDermott, who by this time was in his early 50s, was the South Roscommon commanding officer; Ó Brádaigh, who was in his early 20s, complemented him as the South Roscommon training officer. Together, they built up the IRA in the area. One of their recruits was Sein Scott, who joined the IRA in 1955. Scott approached McDermott and through him met Ó Brádaigh. According to Scott, McDermott was “a very, very sincere man.… He was very dedicated, and he wasn’t prepared to deviate … one iota from what he believed.” McDermott saw that “the British were in the country [and] there was only one way that they were going to leave, through force. He was an absolutely committed soldier.” Scott found Ó Brádaigh “a lovely fella. Very energetic, full of action, very approachable. Ó Brádaigh had sincerity written all over his face. Anything that he said you knew that he meant it.” As a training officer, Scott found him “very dedicated.” He “was good at his job; “he expected you to pay attention, as any good teacher would.”

By the mid-1950s, Ó Brádaigh was involved in training camps outside Longford and Roscommon. These camps, like the IRA conventions, enabled volunteers from various parts of the country to meet each other. Scott’s comments were echoed by an IRA veteran from Belfast, who first met Ó Brádaigh at a training camp in the Wicklow Mountains in the mid-1950s. This volunteer found him “very forceful.”