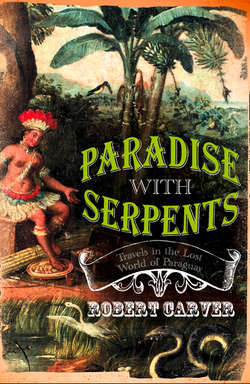

Читать книгу Paradise With Serpents: Travels in the Lost World of Paraguay - Robert Carver - Страница 10

One The Silver of the Mine

ОглавлениеIn the closing years of the 19th century a forgotten man returned to his home town in the Midlands of England, after an absence of more than thirty years. He had long been given up for dead. His father had been a wealthy man, an industrialist who owned lace factories and coal mines. This man had two sons, one who stayed at home and entered the family businesses, the other who went off to seek his fortune in the United States of America; he was never heard of again, and when the head of the family died his great fortune was left to both of his sons, in equal parts, though one of them had vanished, apparently for ever. In his will he had specified that advertisements in every English-language newspaper around the world should be run, each week, for a year, to inform the lost son of his new fortune, so that he could return to claim it, if he was still alive. At the end of that period, if the missing son had not appeared, his half of the family fortune was to go to charity, to found a theatre and a public hospital. His will was done. No one stepped forward to claim half of the great fortune. As a result, at the end of the year, the Nottingham Playhouse and the Nottingham Free Hospital came into being, founded and funded by half this man’s wealth.

Then, years later, sensationally, a man returned from abroad, claiming to be the missing son. My grandfather Roy, at the time a schoolboy, recalled this event vividly. In his sixties, in the 1950s, Roy told me about this prodigal returned: a tall, massively built man who dressed in ‘the American style’, with broad-brimmed hat, long coat, embroidered high-heeled boots, silver Mexican spurs, and a fancy multicoloured waistcoat. He spoke with a marked American drawl, though spoke little but listened attentively to what others said. This man was Charlie Carver, my great-great-grand-uncle. He had returned home, at last, and he had a very strange tale to tell.

He had left England as a restless young man, determined to seek his fortune in the post-1845 gold and silver diggings of Western America. He had taken ship for San Francisco, and had arrived safely. Several letters had been received by the family back in England. Then nothing – silence for over thirty years. What had happened was as follows: in a bar-room brawl Charlie had been hit over the head, and was knocked unconscious. When he came to he could not remember who he was. He had been robbed and had no papers or possessions to give him any clues as to his identity. He found that he had been shanghai-ed and was on board a sailing clipper bound for Australia, enrolled by persons unknown for a bounty, as a common seaman. For the next five years he served, first as an ordinary seaman, then as ticketed mate, on board the big sailing vessels that crossed the Pacific. For all this time he still had no idea who he was, nor where he came from. He acquired an American accent and mannerisms. Then, tiring of the sea, and taking his savings, he disembarked in the States, determined to seek his fortune on land. He tried many trades and moved from town to town, one of the legion of homeless men drifting around the West in the 1970s and 1980s as the frontier closed in. Finally, he found a good position as a mining supervisor, south of the border, in Mexico. He still had no idea who he was, and was known to many simply as ‘Jack’, or el hombre sin nom – the man with no name. One day, inspecting a shaft deep inside the mine, a distant rumble was heard; it could mean only one thing – a fall. The miners, including Charlie Carver, alias ‘Jack’, all rushed for the distant pinpoint of light that was the entrance. They were too late. Dust, rock, pit props rained down upon them. Amid curses and cries of terror they fell to the ground, crushed under the weight of debris. More than twenty men died in that fall, but Charlie Carver was not one of them. He had a broken wrist and a dislocated shoulder, was bruised and cut about the head, but when the rescue party finally managed to dig the survivors out of the rubble, a shocked, semi-delirious voice cried out, in English, for he could no longer recall any Spanish, ‘I’m Charlie Carver from Nottingham – what am I doing here?’ The blows to his head caused by the rockfall had brought back his knowledge of who he was – and erased his memories of the previous thirty years. He had no idea at all what he had done or where he had been in the missing decades. His last memory was of a fight in a low saloon on the Barbary Coast of San Francisco. This time, however, there were clues – his bankbook, his mate’s ticket and discharge papers, his clothes with their tell-tale maker’s labels from San Francisco and Sydney. And there were people at the mine who had known where he had been, where he had worked before, because he had told them before the accident.

After he recovered his health he became a detective on the trail of his own past. He retraced his steps, back to San Francisco. There, in the shipping offices and newspaper stacks where the back-numbers were kept, he was able to trace his life as an anonymous seaman from the arrivals and departures of the grain ships, the muster lists and crew signings-on; on his mate’s ticket he was described simply as ‘Jack of England, Full Mate and Master-Mariner’. He had made his mark on the ticket, not signed it, indicating that in that other life he could not write. Somewhere in his travels he had learnt to use a knife and revolver. He found a keenly whetted blade in a leather sheath hidden in his left boot, and a pair of old, battered, but very serviceable Navy Colt .45 revolvers wrapped in oilskins. On his own body he found scars which he had a doctor examine: they were from the cat-o’-nine-tails, from fist fights, from knife wounds, and at least two puckered scars were old bullet wounds. On his back the doctor also discovered a tattoo of a Polynesian type then only found in Tahiti, made with native ink. It was in the newspaper offices in San Francisco that he saw the advertisements placed for him all those years ago, after his father died. He said afterwards, when he returned to England, that this was the only moment he lost himself, when, alone and surrounded by mounds of yellowing newsprint, he broke down and wept uncontrollably. He said he could still remember the bay rum lotion his father had used after shaving, the memory of it driving him to despair in his loss and pain.

He was now two men. In his mind he was still the young, foolhardy, naive Englishman Charlie Carver, who had only just got off the boat in San Francisco to seek his fortune, but in his body he was the scarred, muscular, hard-bitten middle-aged man who had lived rough across the Pacific for decades, an experienced seaman who had lived under the lash, and a silver mining engineer to boot. The latter persona had been illiterate, nameless and left-handed; the former discovered he had genteel manners, was well-spoken and wrote in a fine, educated hand. He even recalled French poetry and Latin oratory he had learnt at school. He had saved some money – not a fortune, but enough to return to England. He had spoken fluent, colloquial Spanish after his years in Mexico, Texas and California, but the blows to his head in the mine accident had erased all that – and he had become right-handed once again. But he still spoke English with an American accent – and he could still use his weapons. My grandfather Roy was one of several family members who were shown his prowess as he blew a line of empty bottles off the top of a wall, using both his revolvers. He had not missed a single bottle, my grandfather recalled – twelve bullets had hit twelve bottles.

The return of Charlie Carver caused a sensation. His family recognized him immediately: he had changed, of course, but was still in essence the same man in voice and body. When the two brothers saw each other for the first time in three decades they both spontaneously burst into tears. Charlie was now more or less broke. His half of the great fortune had long ago been disbursed to charity, but his brother Bertie then made an outstandingly generous move. He split his own half of the inheritance in half, and gave one half to his brother.

There, by rights, the story should have ended. Now a wealthy man, with enough money to last him the rest of his days, Charlie Carver should have settled down to comfortable provincial obscurity. But he didn’t. He was still gripped by the fever of the silver mines. He had become convinced, like many others, that there was still a hidden Inca city lost in the jungles on the borders of Bolivia, Paraguay and Brazil, a city founded on the wealth of one of the richest silver mines in the Americas. In the 1780s the revolt of Tupac Amaru, a direct descendant of the last Inca rulers, caught the Spanish authorities by surprise. The whole eastern province of what is now Bolivia, then part of the viceroyalty of Peru, was closed to the Spanish for several years. Systematically, the rebels destroyed the extensive gold and silver mines of the region, the survivors retreating eventually into impenetrable jungle to escape the revengeful Spanish. There they founded an Inca city-state which had as its currency and metal of utility the great hoard of gold and silver that the rebels had seized. Iron and copper had they none, so their plates, their knives and forks, their tools and implements were all made of either silver or gold; they also blended these two elements, making that precious metal known to the ancients as electrum. The Spanish never found the lost mines. Those who had known of their existence had been murdered in the rebellion, and the rebels had hidden and destroyed the entrances to these once profitable enterprises. Unlike El Dorado, these mines were not a myth – they had been producing gold and silver under Spanish tutelage before Tupac Amaru’s rebellion. Using old maps, a North American had found one of these hidden mines in the late 19th century, which when opened up began to produce huge quantities of rich gold ore. So, if the quest was a fantasy, it was a least a fantasy with a strong basis in factual history.

Charlie Carver had acquired a map. He would not show it to anyone, would not tell anyone where he had got it, nor would he even say in which London bank vault he had deposited it. He made his plans calmly and carefully. Now, thanks to his brother’s generosity, he had the money to equip a serious expedition. He interviewed a number of candidates for his proposed venture into the jungle to search for Tupac Amaru’s lost city, sometimes called Paititi. One of the young hopefuls was a certain Fawcett, later to be known as Colonel Fawcett, who was to lose his life in the South American jungles looking for just such a lost city of gold. The two did not hit it off. Charlie Carver found Fawcett excessively romantic – a dreamer caught up in a web of fantasy involving a lost Atlantis in the depths of the South American rainforest. Also, and perhaps as pertinently, Fawcett had no money to contribute to the expedition. Eventually a suitable, tough, hard-bitten American was found, equipped with dollars instead of romance, and the two of them set off for Buenos Aires by ship, then up the Paraguay and Parana rivers on the Mihailovich steamer to Asunción, Concepción and eventually up into the tropical wilderness, still unmapped, right on the borders of Bolivia and Brazil.

The old pattern repeated itself. At first, regular letters were received by the family at home in England – then silence, nothing. A long, an overlong silence. Enquiries began to be made by anxious relatives and the British Embassy in Asunción was stirred into action. There was no news. Once again, Charlie Carver had simply vanished into the blue. This time, though, there was to be no miracle, no reprieve. The last people who had seen Charlie and his American partner alive were a small group of Spanish Catholic missionaries, working with Indians only just contacted by whites, on the very edge of known territory. The two explorers had stayed with the priests for several days before departing for the interior, into a region no whites were thought to have ever penetrated before. The smoke of their camp fires had been seen in the distance, coiling up into the sky for several days – then nothing. Some six months later, newly contacted semi-Christianized Indians appeared at the mission with several objects of European manufacture, shreds of cloth, buttons, and a smashed gold-plated, full-hunter pocket watch – manufactured in New York, with Charlie Carver’s name engraved inside it, together with his family address in England. It was all that remained of the expedition. Somewhere in the interior the two men had been killed by hostile Indians. The Indians who brought in the pathetic remains did not even know the tribe which had carried out the attack – they had traded the objects with another tribe, who had had them from yet another. The watch was returned to England, and was even repaired. My grandfather Roy showed it to me when I was a young boy, flicking open the front to show me Charlie’s name engraved in Victorian copperplate script. It still had many dents and bruises on its shell which no amount of repair could ever redress. Somewhere in the jungle the remains of Charlie Carver and his partner lay for ever lost to the outside world. Like so many Europeans they had searched for treasure in America only to find death.

That, too, should have been the end of the story. But it wasn’t quite. Colonel Fawcett, the rejected candidate, got a job as a boundary surveyor in South America, and after his experiences there returned again and again to try to find the lost city of gold and silver, until he too lost his life in the attempt. But before he died he told his great friend the author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle about his theories, about a lost Atlantis in the jungle, Phoenician traders on the River Amazon, about the lost city of Paititi, and about Charlie Carver and his expedition. This information, as we shall eventually see, Conan Doyle eventually put to very good use.

After my book on Albania had been published the distinguished author and former Times foreign correspondent Peter Hopkirk, who had been instrumental in getting my first book published, asked me ‘Where are you going next? You can go anywhere now, you know.’ I replied that I was going to go to Paraguay. ‘Why?’ I explained to him about my great-great-grand-uncle Charlie Carver. ‘To do an “in-the-footsteps-of” book, then?’ he asked skeptically. ‘The trail will be a bit cold after, what, a hundred years.’ No, I replied, not at all. I had no interest in ‘in-the-footsteps-of’ travel books. Besides, Charlie’s footsteps were only too well known – he walked into virgin jungle and was killed by Indians, end of story. What I was interested in were the half-made, half-abandoned places in the world, like Albania and Paraguay – and one could see Paraguay as a sort of South American Albania – lawless, piratical, bandit-ridden and corrupt, where neither tourists nor travel writers usually penetrated. And there was something else. South America had attracted the Spanish and countless other European adventurers who hoped to make their fortunes out of the river of silver and gold that had flowed, at such cost in human misery and suffering, after the Conquest. Yet quite another vision of America had also seized the imagination of the European mind. America could become a place of redemption, a place where the human spirit could be reborn, remade and refined. From its first discovery America had been a realm where imaginary Utopias could be set, and a place European dreamers could actually set sail for, arrive in and set up ideal communities which would, it was hoped, become beacons to mankind. Paraguay, from the first, had been a place which attracted Utopians and idealists. First the Jesuits had experimented with their Reducciones, theocratic communities of Christianized Indians ordered by a multinational caste of Jesuit priests; later 19th-century German nationalists, fin de siècle Australian communists, Mennonites, Moonies, and even renegade Nazis had all tried to set up their colonies in Paraguay. You could make a case that what New England was to Cotton Mather – a place where the exiled English Puritans could attempt to build the City Upon a Hill, which would be a light to lighten the gentiles – so was Paraguay the South American equivalent. In a strange sense the bifurcation of the human mind was reflected in the European’s Manichean obsession with America – a place from which to loot and steal gold and silver, to pillage, rape and plunder, and a place to found ideal communities which would redeem mankind, straighten the crooked timber of humanity, and to build the Perfect City.

Both Charlie Carver and I were heirs to this dual, paradoxical, contradictory tradition, for we were both descended, after all, from John Carver, a Puritan gentleman from the English Midlands who in 1620 procured a vessel in Holland that was renamed the Mayflower, and who was then elected Master of the company of Pilgrims for the voyage, and on arrival in New England was elected first Governor of Plymouth Colony, Massachusetts. Though the English settlement eventually prospered, the first Governor did not. He was shot with an arrow by an Indian while out ploughing the land and died of his wound, leaving behind his wife and children, and his brother who had accompanied him on the Atlantic crossing, one Robert Carver. His descendant, Jonathan Carver, a captain in the Massachusetts Militia, had taken the Union flag of Great Britain to its furthest point west in the years immediately before the Revolution of 1776. He had been the first anglophone to overwinter with the Lakota Sioux, had made detailed plans to cross the Rockies and reach the Pacific coast, and whose travel book – published in London on his return – had proved a sensation all over Europe, translated into at least seven languages. He became a figure in literary London and at Court, and never returned to America. He was a disciple of the French philosophes, and in his tolerant appreciation of Indian culture and moeurs was a century and a half ahead of his time. Our family, I argued, had made a habit of going to America on quests – mine would be in the tradition.

I explained all this over several cups of cappuccino in a London coffee bar to Peter Hopkirk. He thought about it and gave a slight smile of approval. ‘It does sound like an interesting quest. But remember, two Carvers have already been killed by American Indian arrows. Just make absolutely sure you are not the third. Always remember, you can’t write a book if you are killed while researching it. Jonathan Carver is clearly the one to emulate. Steer well clear of silver mines, I should.’ This was very good advice, and I often thought about it later when I found myself in much hotter water than I would ever have thought it possible to get into – and then get out of alive.