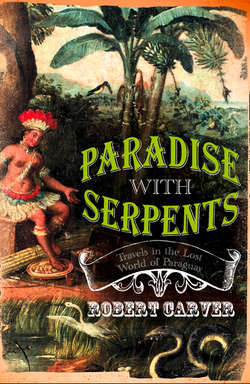

Читать книгу Paradise With Serpents: Travels in the Lost World of Paraguay - Robert Carver - Страница 13

Four Du Côté de Chez Madame Lynch

ОглавлениеGabriella d’Estigarribia sat in the shade under a palm tree by the swimming pool and sipped her grapefruit juice delicately. She had a wide-brimmed straw hat on, her face in deep shadow, yet already the sun had caught the pale, fair skin of her face.

‘Foreigners come to Paraguay, find they can do nothing with the people, become angry, then give up, eventually, and go away again in disgust,’ she said evenly, not looking at me, but rather at the hummingbird which hovered like a tiny helicopter over the swimming pool.

‘Why is it so hard to get things done, for foreigners?’ I asked.

‘Not just for foreigners, for everyone. Some say it is the mentality of the Guarani people, who used to be called “Indians” before they were converted to Catholicism by the Spanish. Then, by a sort of unexplained miracle they ceased to be Indians and became Paraguayans. People say the Guarani live entirely in the present – the past is forgotten, the future unimagined. Remembering things and making plans for the future are both of no interest to them. Promises are made, events planned, but nothing happens – inertia sets in. From the first the Europeans had to use authoritarian means – force, coercion – to get anything done. The Jesuits used to whip their converts on the famous, oh-so-civilized, we are told, Reductions, as well as the ordinary secular colonial overseers on the plantation.’

‘That was a long time ago, surely. What about today, in the new post-Stroessner democracy?’

‘His Colorado Party is still in power. He was displaced by an internal coup because he had grown old and flabby. He was arrested at his mistress’s house. She was called Nata Legal – nata being “cream” in Spanish – that makes her Legal Cream in English, no? What better name for a mistress. He tried to call out the tanks but the only man with the keys for the ignition had gone off to the Chaco for the weekend – so no tanks. There was an artillery duel in Asunción – you can still see the pockmarks in the buildings from the shells – then he was gone, bundled off to Brazil where his stolen millions had been sent ahead. Now we have mounting chaos because no one is frightened any more. Corruption is universal. Everyone takes bribes if they can. Before, under Stroessner, you paid your 10% in bribes to the Party and then you were left alone. Under this so-called democracy you are constantly being made to pay up by everyone, and still nothing is done, because no one is forced to do it any more. You must have noticed the city is falling apart from neglect.’

In her thirties, married and with two small children, Gabriella came from an old Paraguayan family which had been in the country, on and off, since the Spanish Conquest. Her ancestors had come from the Basque provinces of Spain, as had so many of the other conquistadors. Like many of her Paraguyan ancestors, she had spent years abroad in exile, in her case in Miami, in Italy and in England, during the decades of political repression. We were sitting outside in the lush tropical garden of Madame Lynch’s tropical estancia. Once this had been a cattle ranch in open country, belonging to the mistress of the dictator López, now it was a hotel, surrounded by a well-heeled suburb of Asunción, an hour’s walk from the centre of town. You could get a bus or taxi down Avenida España, which made the journey much shorter, but the spate of robberies on public transport meant that many, including myself, preferred to walk. The Avenida España had well-armed police at frequent intervals, as well as motorized patrols during daylight hours, and most of the shops and institutions on either side had highly visible private armed guards sitting outside in plastic chairs with pump-action shotguns or automatic rifles across their knees. At each petrol station there was an army patrol permanently stationed, two or three uniformed men with automatic rifles. This was the route to the airport from the centre of town. If there was a coup d’état or a revolution, this was the route the outgoing government would flee along: clearly they wanted to make sure there would be enough petrol available to get them to their planes. It was the petrol supply for Stroessner’s tanks that had been under lock and key, I later learnt, when the crunch had come, not the ignition keys. Clearly, this government didn’t intend to make the same mistake. Stroessner still gave maudlin interviews to journalists from time to time from his hideout in Brazil, where he bemoaned the fact that he was a much misundertood former dictator – but then they all say that, those that survive. An avowed fan of Adolf Hitler, his secret police, known as the Technical Service, were among the most feared in South America. Cutting up political opponents with chainsaws to a musical accompaniment with traditional Paraguayan harp music was a popular finale, the whole ghastly symphony played down the telephone for favoured clients. Like his local hero the Argentine dictator Juan Perón, Stroessner had a taste for young girls – very young, pre-pubescent. When a daring journalist had once asked Perón if it was true that he had a 13-year-old mistress, he replied, ‘So what? I’m not superstitious.’ His reputation among Argentines had soared after this was revealed, the ultra-young mistress being seen as a sign or both power and virility. The 13-year-old in question used to parade around Perón’s apartment dressed in the dead Eva’s clothes, to the slothful admiration of her ageing beau. Stroessner was reputed to favour the 8–10 age group. His talent scouts waylaid them outside school, from where they were taken to discreet villas to be enjoyed by the Father of his People. If they performed nicely they and their parents would be sent on a free holiday to Disneyland in Florida, the nearest Paraguayans can get to Heaven without actually dying first. Stroessner, the half-Bavarian, half-Indian dictator had sent a gunboat down the river for Perón, the mulatto dictator, when he had taken refuge in the Paraguayan Embassy, after his overthrow. Forced into exile, Perón had fascinated the young supremo by recounting his adventures and reminiscences. ‘They used to worship my smile – all of them!’ he cried. ‘Now you can have my smile – I give it to you!’ and here he had taken out his brilliant set of false teeth, and passed them across the table to the startled Stroessner. Perón had found Paraguay too dull, and he had to agree to abstain from political intriguing in Argentina, which was irksome, so after a short period of rustication up the river he had taken himself off to the Madrid of Generalissimo Franco, where he lived in exile with the mummified corpse of Eva Perón upstairs in the attic of his Madrid villa, surrounded by magicians and occult advisers. The mummifier, Pedro Ara, who had taken a year over his task, had used the ‘ancient Spanish method’ and had charged $50,000 for his work, a bill that was never paid. Throughout the last weeks of Eva’s agonizing illness the embalmer had stood close by on guard in an antechamber, night and day, waiting in anticipation, for he had to start the process of mummification the instant she died ‘to render the conservation more convincing and more durable’. Her viscera were removed entirely and preserving fluids were sent coursing through her entire circulatory system before rigor mortis set in. Some areas of her body were filled with wax and her skin was coated in a layer of hard wax. The complete process was slow, painstakingly slow. After the fall of Perón, the military mounted ‘Operation Evasion’ in which the body of Eva Perón was ‘disappeared’ to prevent her becoming the focus of a popular cult; for many people, particularly women and the poor, she has already become a saint.

The son of a First World War German officer, Lt-Col. Koenig was given charge of the body, and he showed it to a delegation of Peronist CGT trades unionists to show that the military had not outraged her body. After this the mummy was hidden in various military barracks: but the people always found out where she was cached, and flowers, candles and votive offerings appeared as if by magic outside each new hiding place. For a long time Colonel Koenig refused to bury the mummy of Eva: some said he had fallen under her spell and used to sit up at nights talking to her as if to a lover, perhaps indeed having fallen in love with this masterwork of the embalmer’s art. Eventually, under mysterious circumstances, the mummy was exhumed and smuggled out of the country to the Vatican by an Argentine priest, Father Rotger, aided by a posse of Italian priests well versed in the black arts of corpse vanishings. Finally, it seems, Koenig had managed to force himself to put to earth the mummy of Eva. ‘I buried her standing because she was male,’ he said later, and this vertical interment was confirmed, for when the mummy was examined in Rome the feet had been destroyed by the weight of the body forcing down on them. It was rumoured that even when buried, Eva had been consulted on various occult matters by the military, and burying her standing up made such consultations easier – the casket only had to be opened at the top, with a sort of cat-flap on hinges. Originally, Eva’s mummy had been exhibited in a glass casket to her adoring public, her hands holding a rosary given her by the Pope; now her body vanished into limbo, finding its way by unknown means into Juan Perón’s hands again in Madrid. After Eva’s death, Juan Perón had made her brother Juancito fly to Switzerland and sign over her numbered accounts into his own, Perón’s name; following this Juancito was conveniently killed in a car accident in Buenos Aires, and his skull ended up being used as a paperweight by Captain Grandi, a military official. Torture and bullfights had both been banned in Argentina in 1813, after the Spanish had been expelled. Perón reintroduced torture, including for women, especially to the genitals. His chief torturer was one Simon Wasserman, a Jewish police official. Like Stroessner, Perón was half-Indian. His mother was so dark that in the racially prejudiced Argentina of the era, she could not be presented in public. Perón had a sense of humour, however; when criticized for living with an actress – Eva was a famous star of the Argentine radio and cinema – he replied, ‘Who do they expect me to sleep with – an actor?’ He was just about to confiscate all the Catholic Church’s property in Argentina, and turn the Cathedral in Buenos Aires into a social centre for trades unionists when he was overthrown. His antecedent – also of part-Indian descent – was Dr Francia, the first dictator of Paraguay after independence from Spain who successfully nationalized Church property, and said, ‘If the Pope cares to come to Paraguay I shall do him no greater honour than to make him my personal confessor.’ Dr Francia got away with it because he had eliminated all opposition from his rivals, and because Paraguay was so far away and so difficult to get to. Many people in Europe still do not know where the place is, including, presumably, the editors of the Penguin History of Latin America, who give the country a complete miss.

Stroessner observed all of Perón’s antics and travails from up the river, and carried many of the murkier aspects of Peronism into practice himself in later years, particularly torture and the cult of the personality. There was even a ‘Don Afredo Polka’, the polka being the national dance, though nothing like a polka anyone in Europe has ever heard. Though the Paraguayans do not like you to say so, Paraguayan history sometimes seems to be a grotesque parody of what has already occurred down south. If the saga of Juan and Eva Perón reads to European eyes as a bizarre excursion into Grand Guignol, something from the pages of a magical realist novel by Gabriel García Márquez, it is worth noting that Márquez himself worked when a young man as a journalist on the Buenos Aires newspaper Clarín during the Perón years. To those who know South America at all, Márquez’s fiction is closer to reality in that continent than many Europeans would credit.

The Paraguayan attitude to their neighbours the Argentines was both complex and paradoxical. They professed to dislike and distrust them, but also, at some level, they admired and aped them. Their slang insult for them was ‘pigskins’, possibly because they were pink-skinned and hairy, like pigs; the Argentines responded by calling the Paraguayans ‘redskins’ and ‘savages’, but there were, of course, many intermarriages between the two peoples. Gabriella’s mother had been an Argentine. ‘¡Cuidado!’ she warned me, her voice rising. ‘Be careful! ¡Chantar! You know this word? To boast, to brag, to bullshit, to bluff- all Argentines are the world’s experts at chantar.’

I mentioned to her later that there was a possibility that an Argentine guide might be willing to take me into the interior in his jeep. ‘He will cheat you,’ she had said, though she didn’t know him, and had heard nothing against him. To be an Argentine was enough. Not that she, nor anyone else I ever met had any enthusiasm for the Paraguayans, either. ‘We overvalue foreigners, particularly Europeans,’ Gabriella had told me. ‘We Paraguayans do not trust each other. This is a land of false smiles and forced laughter. Many foreigners are taken in by this – the happy, smiling Paraguayan, true child of nature, and so on. Bullshit.’ I had already noticed that everyone I spoke to had quite naturally disparaged the local climate, food, people and products. Nothing, it seemed, was as good as in Europe. Yet as an outsider this did not seem at all accurate to me. Few of the people I spoke to had actually been to Europe, and when I told them a few facts about the place they were alarmed, even horrified, and often even openly disbelieving.

The first, most obvious natural advantage Paraguay possessed was its mild sub-tropical climate, in which palms, bananas, oranges, lemons, limes, pineapples, sugar cane and hundreds of other exotic flowers, ferns and orchids flourished. The second was the great sense of space, and the complete absence of any sense of urgency or haste. The country was the size of Germany or California, and had very few people in it, mostly concentrated within a hundred kilometres of the capital; a third of the land area was still virgin forest, the rest agricultural or bush. Away from the towns you could stand on the top of a gentle hill – the country was very flat – and gaze around you 360 degrees and see nothing but forest and fields as far as the eye could see – no people, no houses, no roads. When I told Paraguayans that this was almost impossible in Europe, that we were densely packed, crammed in on top of one another, they were very surprised. When I told them also that in many places the government had the power to tell you what colour you could paint your front door, what type of windows you could or could not have in your house, what sort of tiles you could put on your roof, they were both amazed and indignant. ‘That is tyranny!’ they exclaimed. ‘No Paraguayan would ever accept that. We may have a rotten political class, but they would never dare interfere with our private lives or property like that.’ Many showed me by their expression that they were skeptical about what I told them of European restrictions and regulations – that you could not smoke in buses, trains or many restaurants, that the police photographed your car number plate and sent you a fine later if you went too fast, that the Customs in England could confiscate and crush your car if they felt you were bringing back goods from France they thought you might sell. ‘Don Roberto, with courtesy and respect, of course, you must surely be mistaken – these things are impossible, inconceivable in a great continent of culture like Europe.’ I told them that I lived in such a place of intense restrictions. It was called a Conservation Area, and any changes at all to the outside of my house – paint, door, windows, tiles – had to be approved by the local government council, in order to preserve the character of the area. ‘How can you live like this? It is like being in a prison! No wonder so many poor Europeans come to Paraguay to live! We are free! We do what we want. Your house is not your own – it is the government’s, evidently.’ And moreover, I added, in Britain it was illegal for any private citizen to own a handgun. If you were caught with one you went to prison for three to five years. This was always the straw that broke the camel’s back. I was obviously engaged in high-level chantar. Not to be able to own a pistol to protect your family from criminals? It was like saying to an Englishman that the ownership of handkerchiefs carried a three- to five-year gaol sentence, the two items being about as common as each other repectively in Paraguay and England.

After barely suppressed looks of complete disbelief someone would always ask, But why do people tolerate such restrictions – why do they not make a revolution? ‘Because they – we are used to such government restrictions. The State is incredibly powerful in Europe, and it takes on more powers every year. The few that object sell up and leave quietly – they are welcome to go. For the rest they accept, they complain, they grumble – but they accept.’ At this there would be shakings of heads and sighings of disapproval. ‘Never in Paraguay – never in South America!’ they always concluded. Indeed, the contrast between Europe and Paraguay could not be sharper. Paraguay was still in essence an 18th-century state, with a very small and almost completely powerless government. Life was dangerous, often violent, and there were many assaults and robberies, but there were very few constraints upon the individual’s freedoms, including the freedom to starve, be unemployed, and live with no social security or health service. You could buy land, put up any sort of house, fly in and out of the country in your own plane, own firearms, pay no income taxes – and precious few other ones either. Private property was sacrosanct. To enter another’s land without asking was to risk being shot as dead as a potential malviviente. Bureaucratic interference in people’s lives was minimal. The state bureaucrats only turned up at the office once a month to collect their salaries. You could park, piss, smoke and drive where and how you wanted to.

The individual egotism and selfishness of the country could be gauged by its completely anarchic and manic driving on the roads. No one stopped for pedestrians or for any other reason either. If the police wanted to halt traffic they had to erect a barrier that would seriously damage vehicles if they drove into it. There were no safety nets to protect the old, the young or the infirm. The street children of Asunción had formed a Union, and they demonstrated frequently – on the streets, of course – for ‘dignity and respect’, and protested against a recent law which had sought to ban children under 14 from working. This edict caused great resentment, and thousands of children had protested that they were being denied the chance to support themselves. Like everything else, age in Third World countries and the West carried an entirely different freight of meanings. In Paraguay, as in Spain, the age of consent for sexual activity for girls was 12. In Paraguay, young ladies ‘came out’ on their fifteenth birthday – there were photographs in the local papers of these belles dressed up in white gowns and squired by their fathers at full dress Society balls. Life expectancy, so long we in the West are almost like Swift’s Struldbruggs, and so short in the Third World, created quite different demands on people. In the West sexual activity among young people is discouraged for as long as possible, and seen by progressive middle-class adults as a bad thing, while in Paraguay it was encouraged and hastened in a land where a large family was one’s only chance of survival in old age, and early, unexpected death was a frequent reality. To be a mother at 12 or 13, so shocking as to be seen as a social problem in the industrial West, was a simple reality of life in countries like Paraguay. In the moral panic that surrounds children’s sexuality for many adults in England it is often forgotten that once England was itself a Third World country, where people bred early and died young. Shakespeare’s Romeo was 14, one recalls, and Juliet 12 when their love affair took place. The Elizabethan audience had not been shocked. This had represented late-medieval reality.

Gabriella was the first Paraguayan I had met who had lived for an extended period in Europe, and who knew both cultures intimately. She had worked for the BBC World Service in London and her husband had worked in import-export. They had managed to save enough money to buy a small flat in a remote suburb of outer London. This, she told me, they rented out to a fellow South American. Like so many people from unstable economies with erratic currencies all over the world, a small stake in British real estate was a hedge against uncertainty at home. I asked Gabriella how she managed in Paraguay now that most of the local banks had collapsed. ‘I only use my bank account in London,’ she replied. ‘I have never had an account here. I wouldn’t trust any South American bank. When I want cash I put my UK plastic in the hole in the wall here, and draw out US dollars in cash.’ This, I learnt, was quite common for middle-class South Americans in Uruguay, Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil. You had your bank account in Miami, in Dallas, in London, New York or the Cayman Islands; all your money you kept out of the local economy, because neither the currency nor the banks could be trusted. Those who had ignored this simple rule of financial security in Argentina and had trusted the government’s one-peso-equals-one-dollar policy had lost their money when the government defaulted, devaluing the peso and freezing bank accounts.

The government had, in effect, stolen the people’s money by reneging on their promise of parity. For the last two centuries South America had been a sink for capital. You could make money fast, but if you trusted the local banks or the local currencies you lost the lot, eventually. The ideal export product was cheap to make in South America and very expensive to sell for dollars or pounds abroad – hence the huge popularity of cocaine and marijuana as cash crops, and the fortunes made by processing and exporting these drugs in Paraguay and elsewhere. The whole country was dotted with illicit, hidden airstrips in remote places, where light aircraft – avionettas – landed and refuelled, carrying out drugs, contraband liquor and cigarettes, and carrying in guns, dollars and essential spare parts. These strips were constantly being discovered by the police, though very rarely were any planes intercepted. With extended fuel tanks fitted the standard light plane could reach Miami or Dallas – or private airstrips in the desert in Texas or Arizona – without having to land to refuel. The rich – and the criminal – all had private planes.

Since the arrival of the Spanish, and even before, South America had been a place of plunder. The great empires of the Aztecs and the Incas had been based, too, on military conquest and the exploitation of subject peoples; both of these tyrannies had practised extensive human sacrifice, the victims taken from subject and defeated peoples. This continent had long been a place where people imposed their will and seized what there was – gold, silver, slaves, sugar, cocaine; the products changed, but the economy of looting continued. It was normal and natural for South Americans to go into exile when things went wrong. The concept of life was still colonial, with strident nationalism in local politics, mirrored by a furtive, clandestine export of capital away from local risks – instability, revolution and chaos. When the time came to flee the exiles already had their money, their houses, their other lives in safe havens prepared abroad in safer places. Gabriella and her husband lived in Paraguay – but only just. Their capital, their property was in London. They rented in Asunción because it was not secure to own. Everything in Paraguay was very cheap to buy by US or European standards, and everything was up for sale. In the past, people had put their money into real estate because they didn’t trust the local banks. Now they wanted to sell and go away again. Stroessner had been bad, but this pseudo-democracy where everyone was corrupt and everyone stole and no one was accountable was worse. You could buy houses, apartments in Asunción for half, for a third even of what people were asking, Gabriella told me. All the flights out to Miami and Dallas were booked up for months in advance, and the planes arrived all but empty. Gabriella and Hugo had shipped down some furniture from Miami when they came back. That could be sold quickly or shipped out again if things went wrong – Hugo had ‘Italian papers’ so they could always go to Italy, she told me. People in Paraguay talked of having ‘papers’, not of being a particular nationality. It was where you were allowed to live that counted. ‘Life is easy in Paraguay, it is cheap and there are servants, but it could all go wrong very soon,’ Gabriella told me. They had only been back a matter of months, and they were already thinking they might have to leave again. Almost unknown to the prosperous, secure peoples of the developed West, millions of the educated, the skilled, the able in the Third World live like this. In Sudan, in Albania, in Sierra Leone, Malaysia and Indonesia people watch nervously for the signs that some imminent collapse might be just round the corner. In Paraguay, the first casualty of any coup d’état would be the liberal media; there would be no place for a BBC reporter under a military dictator.

Before Stroessner came to power there had been a long, bitter civil war in Paraguay. As many as a third of the population had been killed – no one was sure how many had died. Lawlessness and banditry had been rife. Stroessner had taken over and enforced both peace and stability. Like Spain after the Civil War, the exhausted country had acquiesced. Yet with his peace came torture and institutionalized corruption, the eclipse of civic rights, and great injustice. As many as a third of the remaining population had fled abroad, mainly to Brazil and Argentina. Some had come back but many still stayed away. Paraguay was a risky place, but the safer countries they had fled to before, Brazil and Argentina were now themselves places of disorder, chaos and financial collapse. The press was full of massive banking scandals, directors who plundered their banks and then fled. In Argentina, the economic collapse had caused riots, kidnappings and massive unemployment. In a poll, 57% of young Argentines under 25 said they wished to leave the country as they had no faith in its future. The world was divided into those countries everyone wanted to leave and those everyone wanted to get into. The latter group was very small, and mostly run by Anglo-Saxons or Scandinavians. Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil were all immensely rich – but then so was the Congo. There was no use in great mineral wealth, skilled and talented people, and bountiful natural resources if there was corruption, if everyone stole from everyone else. In such places your money, and in the end you and your family, were only safe somewhere else.

All over Asunción there were large, unfinished tower blocks, now rotting with decay. They had been overambitious for the scale of the city, clearly. Why had anyone ever put money into starting to build them? The price of entry into Paraguay during the stronato was investment in the local economy, Gabriella told me. The high-ups in the Colorado Party had owned construction companies which took the investors’ money and ran up these partly completed structures, syphoning off most of the money into their bank accounts abroad, then simply abandoning them. Corruption under Stroessner became endemic and systematic. Even the very poorest had got into it. The ‘hormigas’ as they were called, the ants, plied to and fro across the border with Brazil, smuggling goods to and fro by hand, in bags and cases, bribing the Customs each time. ‘Contraband is the price of peace,’ Stroessner said. Smuggling, bribery, corruption and illicit activities of all kinds became the bedrock of the economy. The country began to forget how to work. Once oranges, bananas, tropical fruit of all sorts had been grown commercially and exported to Brazil and Argentina. Now all these products were imported from Brazil, from Colombia. Under Stroessner everyone had been able to become a small-time contrabandista. One of the reasons for the complete absence of any coherent collectivist left opposition was the petit-bourgeois, small capitalist mentality that reached right down to street traders and Indians selling vegetables in the streets. There was no local car industry to protect in Paraguay, unlike Brazil and Argentina, so shiploads of second-hand cars came up the river, bought in job lots in the southern USA. And stolen cars poured across from Brazil, driven in from Sao Paulo, the Customs officials on both sides bribed. The contrast between the beggars on the streets, the mendicant cripples, the unmade roads, broken pavements and leaking water mains in Asunción, and the massed ranks of brand new BMWs and Mercedes was marked. The President and his wife were both alleged to drive cars stolen in Brazil – a local newspaper had exposed the story and printed photos of them getting out of the hot cars which had been hijacked from the streets of Sao Paulo. I mentioned J. K. Galbraith to Gabriella – she was a journalist after all – and suggested that his dictum of ‘private affluence, public squalor’ applied to contemporary Paraguay. She had heard of neither Galbraith nor his well-known equation. It was Gabriella, also, who denied that she knew the meaning of the word ‘cacique’, a term used all over the Hispanic world for a local political boss, but which came originally from a South American Indian derivation. I saw it printed in the local Asunción papers many times. The previous President of Paraguay, Carlos Wasmozy, was in gaol for four years, for having embezzled US$4 million – that was all they could find, anyway: a year for every million stolen. Getting corrupt officials into court at all was hard. ‘Impunidad’ – impunity – was one of the problems. Bribery was so rife that a little well-spread money prevented much from coming into the open or, if it did come out, from anything being done to prosecute or convict. The ordinary policeman was paid US$100 a month – just $25 a week, the same as Gabriella paid her cleaning maid – and the police had not been paid for three months because the coffers of the State were empty, or so it was claimed. The prison guards had not been paid for a year. In the remote north of the country the press reported that these prison guards were being fed by the prisoners’ families, who also brought food in for the inmates, who otherwise would have starved, there being no official funds to feed them. Under such circumstances corruption and bribery were inevitable. Wealthy prisoners who by bad luck found themselves in gaol soon managed to bribe their way out again: the papers frequently reported on such cases.

The question as to why no public servants had been paid for so long was easily answered: the government had run out of money, and if they simply printed more banknotes, as South American governments had in the past, they would fuel inflation and cut off the IMF and International banks as potential donors for further hard currency loans. ‘You will have noticed how many of the waterpipes in the streets of Asunción are broken,’ Gabriella had remarked. I had noticed. There were leaks everywhere, spilling out into the streets, flooding the pavements, a side effect of which was vigorous tree, shrub and weed growth beside the roads, among the cracked pavements, and even in the potholes of the lesser used streets. Asunción had been hacked out of sub-tropical jungle, and given half a chance the jungle would reclaim it again.

‘The water company, State-owned, borrowed US$10 million for repairs from a US based international agency,’ she continued. ‘The construction company that got the contract was owned by the head of the water company’s brother. A $10 million hole was dug in the ground, achieving nothing. No leaks were repaired. The hole was abandoned. Obras inconcluidas – “abandoned works” – should be the Paraguayan national motto. The $10 million disappeared abroad into offshore bank accounts. The water company officials have not been paid for more than a year. Now we have a large, useless hole, a $10 million debt, and a leaking water system. About a third of all the water is lost through leaks and broken pipes. Scientific tests have shown that the water is seriously contaminated – cholera and typhoid among other infections are in the system.’ Before Stroessner there had been no piped water at all, just as there had been no airport, or paved, metalled roads. People had their own wells, or depended on water sellers who toured the capital with mule-drawn tanks. Now there were frequent electricity blackouts, and the petrol stations regularly ran out of fuel. Those who could afford them had emergency electricity generators. In spite of the fleets of stolen luxury cars, Asunción more closely resembled a decaying African city, falling apart after the European colonials left, than anywhere in Europe. Stroessner had attracted immigrants and capital because he accepted gangsters on the run, fraudsters, conmen, Nazi war criminals with stolen loot, and because he offered a stable, authoritarian government which built roads, created infrastructure, and limited corruption to himself and his cronies. Now he was gone what he built up was in no way maintained or replaced. Paraguayans had not paid for these things, foreigners had. They felt, like colonial peoples newly liberated, no debt to the past, no sense of possession. His successors were bent purely on looting the country and fleeing abroad with what wealth they could steal. According to a report in Ultima Hora, the only income the Paraguayan government now had was the monthly US$16 million from Brazil for hydroelectrical power Paraguay exported across the border. Without this sum the government would be completely bankrupt. Yet it was not enough to pay even the civil servants. There had been a plaintive letter published in the papers from Paraguay’s ambassadors abroad. They, too, had not been paid for a year, and the rents on their embassies and residencies were in default. Unless money was forthcoming, embassies and residencies could soon be repossessed. This was all a minor nuisance for the few very rich in Paraguay, with their money abroad in offshore havens, their houses with tall walls built round them manned by armed guards, or sequestered on 200,000-hectare ranches. For the great majority of the country, it made life a grinding misery. Paraguay was potentially a very rich country, fertile and replete with mineral resources, yet so badly was it managed, and so feebly was it cultivated that it imported even basic foodstuffs. The supermarkets were full of goods brought in from Brazil, Argentina and Europe that could easily have been grown domestically.

‘You cannot fire public servants in Paraguay,’ Gabriella had told me. ‘Once appointed, it is a job for life. Under Stroessner, the administration of the city of Asunción was carried out by 400 civil servants, who worked from 8.30am to lunchtime, then finished. They were all members of the Colorado Party. Although they worked slowly, and very easy hours, they did actually turn up and did actually work. Everything was kept in good repair, and new roads were laid, parks maintained and basic services ensured. Then, after Stroessner was ousted, the Radical Liberal Party managed to get into power in the Asunción local government. They could not fire the 400 Colorado Party civil servants, but they could hire 1,000 new civil servants – all Radical Liberal Party members. These are known as “gnocchis”. There is a tradition in the River Plate countries, Uruguay, Paraguay and Argentina, that civil servants eat gnocchi, the Italian potato-based pasta, on pay day every month, usually the 29th of the month. It’s an old tradition. In time, the civil servant who is purely a political appointee and merely turns up every month to collect his salary, became known as a gnocchi. This is how the political parties fund themselves – they reward their followers with civil service jobs when they are elected on the understanding that the party gets a kickback of between 50% and 90% of the placeman’s salary. The gnocchi can have several jobs of this sort as all they have to do is turn up once a month to get the salary. Well, the Colorado civil servants naturally didn’t turn up for work any more – they couldn’t be fired, and Stroessner didn’t frighten them now he was in exile. And the Radical Liberals didn’t turn up because they were gnocchi and paying much of their salary back to the Party. So there was no civic administration and nothing got done and things started to fall apart. The disgusted citizens of Asunción voted out the Radical Liberals after this happened, and voted in a minor party who immediately appointed 1,000 of their own members on the same gnocchi principle. The local government now has 2,400 employees, none of whom turn up except to get their salaries. And none of them can be fired. As a result no maintenance work is done, no local taxes collected, and the infrastructure of the city is falling apart. And as there are no taxes collected, none of the civil servants have been paid for at least a year, sometimes longer.’ The logic of all this, I had to admit, was inescapable.

A wave of nostalgia was now spreading for the ‘good old days’ of Stroessner when the firm hand had meant a degree of order and efficiency, and a level of corruption that now seemed positively moderate. ‘Ya seria feliz y no sabia’ I had seen as a printed car rear-window sticker all over the city – ‘then we were happy and we didn’t know it’. Liberalization brought street crime, robberies, rapid inflation and a collapse of the infrastructure as well as the banks. Diphtheria, cholera, malaria, yellow fever, dengue and leprosy were all on the increase. There was no foreign exchange to import necessary drugs and medicines. Even the water supplies in the hospitals were polluted. ‘Will you stay in Paraguay or go abroad again?’ I asked Gabriella. She thought for a long time and gazed away from me into the middle distance. ‘I don’t know. We’d like to stay. It’s much easier here than Europe. But if the chaos grows … I don’t know.’ ‘Easier’ meant cheaper, with servants, in a pleasant climate. ‘Where would you live if you could?’ I asked. ‘Miami,’ she replied without hesitation. ‘It’s a terrific city – culturally Hispanic but run by Anglo-Saxons, so everything runs properly. And so safe.’

Everything is relative. In England, Miami is a byword for violent crime, drugs, gangs and disorder. But from the perspective of Asunción it seemed as appealing as Switzerland. ‘We need a government of honesty, austerity, and lack of corruption,’ one Paraguayan had said to another in an Ultima Hora cartoon. ‘That is to say, a foreign government,’ his friend had replied. Gabriella gave me a list of useful contacts, people who would help give me an insight into the country – a radical priest, a German settler, a US drop-out living with a Paraguayan girl, and many others. ‘Don’t get too hopeful,’ she cautioned me. ‘You will be promised many things in Paraguay, and none of them will come to pass. There is much talk and almost no action. Everything that works here is run by foreigners – it has always been the case. This hotel is an island of German efficiency. If the Germans left Paraguay – and one in forty are of German descent – the country would go back to the jungle. And they are leaving, the foreigners, for Brazil, and Bolivia, those who can. The civil service wages bill consumes 87% of the government budget even when they have any money, which at present they don’t. What the private sector doesn’t provide simply doesn’t get done. Government here equals a parasitic class which provides nothing.’

My own observations walking round Asunción confirmed the dereliction. In the municipal gardens there had been a man in rags sweeping leaves off the path with a cut palm branch. He wore no shoes and looked more like a tramp than a public servant. He took care not to disturb the beggars sleeping on the wooden slatted benches, on the grass, under the palm trees. There were very small children, from four upwards, who strolled about trying to sell chewing gum and sweets from cardboard trays. Lunatics from the local asylum wandered about aimlessly, cackling and grinning, dressed incongruously in old-fashioned evening dress – tailcoats, striped trousers, spats but no shoes – as a result of international charity clothing donations. The asylum had no money to feed the inmates, so they had been turned loose to wander the city and fend for themselves, scavenging rotting vegetables from the gutters, left by the Indian street sellers. They capered and loped about, these lunatics, distinctive in tailcoats stained by diarrhoea, adding a carnivalesque, grotesque note to the tropical dirt of the Central Business District. Neither the police nor anyone else paid the slightest bit of attention to them: like the vultures hunched on the telegraph wires, watching for a stray dog that had escaped attention, and the Makká Indians from the Chaco who drifted about in loincloths and painted cheeks, trying to sell bows and arrows, they were simply part of Asunción’s dusty, stinking reality. In the air hung the smell of foetid, fermenting human excrement and urine; all these people were living, eating and eliminating in public, in a hot, humid tropical climate. They, like the street children and the beggars, slept in the parks. In daylight the streets were full of European-looking businessmen and their BMWs. At dusk these vanished to the suburbs, and the town centre became an ill-lit Indian-haunted place where pistoleros and whores roamed about and the police stayed mainly inside their fortified barracks. If the police had withdrawn completely the city would be given up to looting and uncontrolled violence: and the police had now not been paid for several months, and were extremely disgruntled. If the government could find no money to pay the police they would not suppress the next pro-Oviedo demonstration. And then there would be a revolution, democracy would be closed down, and a hard-line dictatorship set up again. Liberalization led to chaos and riot and so back to dictatorship again. It was like the ancient Greek city states, an endless swing between repression and licence.

All of this swirling, picturesque, smelly chaos was kept out of the Gran Hotel by high brick walls, 20 foot or more, and an armed guard at the entrance to the grounds with a machine-gun and stern glance who kept would-be intruders at bay. I had negotiated the room-rate down from US$100 a day to $40 a day, and thought I had done well. When I told Gabriella what I was paying she snorted, and went to harangue the middle-aged woman, once an ambassador’s wife it was said, who managed the front reception. After a short altercation in Spanish, Gabriella informed me that as from today my room rate had been reduced from $40 to $30 a day, and when I went off into ‘the interior’ as the rest of the country was quite unironically referred to by the people of Asunción, the hotel would keep my room for me and all my luggage in it, ready for my return, at no charge to me. This was quite usual, Gabriella told me. ‘There is almost no one staying here. They have dozens of rooms and almost no guests. They are lucky to have you.’ The hotel was a pleasing old colonial affair in the Spanish style, with loggias and white stucco Tuscan columns, dark oxblood-red walls, roman tile roofs over verandahs. The windows had white-painted louvred shutters and the ceilings of the rooms were high, to keep the air cool. Each room opened out on to a courtyard garden planted with banana and citrus, bougainvillea and palms; ferns and bright orchids hung in baskets. The soil was dark red and the white-clad Indian gardeners moved about slowly, directing water, pruning, hoeing, weeding. When a guest passed them they stopped work, turned to face the passer-by and, smiling, said quietly, ‘Buenos días, señor’. This is how it must have been throughout much of Paraguay under Stroessner – calm, obsequious, well-ordered, the peons knowing their place. Now the Gran Hotel was an island of tranquillity in a sea of chaos and disorder. Behind the swimming pool lay a dusty tennis court, and beside this, shaded by trees, a tall metal cage which held two brightly coloured green parrots: at dusk these birds gave off terrible shrieks, as if heralding the end of the world. They were fed with cut-up fruits by the gardening staff – oranges, bananas, mangoes, and fresh leaves from tropical trees. They perched on one claw and slowly, delicately, nibbled at the fruit held in the other. There was also a large toucan in a separate cage on the other side of the swimming pool. This bird clambered up and down the wire, as if imprisoned in an adventure playground. He too lived on fruit provided twice a day, and was shy: if you looked at him, he avoided your gaze and trundled off, embarrassed, getting out of your eye line. Birds in cages always make me feel sad and depressed: not only do I feel sorry for the imprisoned birds, but it also reminds me of our own incarceration. I had felt oppressed and imprisoned in Europe, and now I felt oppressed and imprisoned in the gilded cage of this luxurious hotel and its grounds in Asunción. In Europe I could sit on a park bench in public, unnoticed and unthreatened – I was invisible. In Paraguay I felt unsafe in all public spaces. The eyes that searched me over were not friendly. It was noticeable that Paraguayans of European extraction spent as little time as possible in public spaces, passing through them in cars, usually, whereas the mestizo and Indian population, on foot, seated or sprawled on the ground, lived at ease in these spaces. My race, my pale skin made me an intruder.

Behind my room, in a small courtyard garden into which one could wander, was another prison, a small menagerie with hoopoes, cranes, two small monkeys in a cage, a couple of miniature deer of the muntjak type, and a large terrapin. As menageries go this was deluxe – leafy, calm, shady and private – but like the hotel, it was still a prison. The trees and shrubs in this small haven were dense and in deep shadow for much of the day. The birds and animals were so well hidden that you could be almost on top of them before you saw them. And everywhere, in the gardens, in the air, all around one, was Paraguay’s spectacular birdlife – on the wing, perched in trees, darting between bushes, a rich burble of song. Like Manaos in the Brazilian Amazon region, Asunción was a small city in a clearing in the middle of the jungle. For thousands of miles in every direction there was nothing but largely empty countryside – empty that is of human activity. For the birds flying across Asunción, or attracted by the food, the several acres of gardens the hotel offered to them was just more native jungle as a convenient stop-over. Living in the depleted, overpopulated Northern Hemisphere where any signs of wildlife are rare and fugitive, I found the explosion of bird noise in Paraguay startling and sobering. It was evidence of what we had lost by our overbreeding. Perhaps Europe had been like this in the Middle Ages. It was a real pleasure just to sit in a cane chair outside my room looking at and listening to the birds. The only thing I can compare it to is being inside a tropical aviary at a zoo. Tiny hummingbirds smaller than the first joint on my thumb, rainbow coloured with iridescent green the dominant shade, hovered and darted by a hibiscus plant, long thin beaks moving inside the flowers to search for drops of water or nectar. I would sit for timeless periods, completely enraptured by the sight, the wings of this tiny dynamo revolving thousands of times every second, so fast all one saw was a blurr, whirling beside the tiny body. The birds seemed completely indifferent to the ghost-clad gardeners who shuffled slowly to and fro, or to the few guests, who like me, sat outside in the shade drinking in this tranquil atmosphere. Overpopulation, pollution, the depleted environment are realities of our era; to come to somewhere like Paraguay was to realize just how much had been lost.

I walked back with Gabriella to her house, which was less than ten minutes away on foot: it was a small, neat semi-detached building with a thin strip of garden in front and a larger one behind. Workmen were engaged in some maintenance at the front. The whole neighbourhood was tidy and prosperous-looking, with well-kept gardens, lush shrubbery, and clean streets. It reminded me of middle-class parts of Los Angeles. I asked Gabriella which suburb of London it most resembled, as she knew both cities well. ‘Kensington,’ she replied immediately. ‘It is where the embassies are and where the wealthy live.’ I asked her what her house would be worth. ‘Normally US$60,000, but because so many people are trying to sell, you could get a place like this for $40,000 – even for $30,000. People are only paying about half the asking price at the moment.’ To put this in perspective, Gabriella was paying her maid $25 a week: ‘and my mother thinks I am paying her too much – she only pays $15.’ High unemployment, low wages, few people, inexpensive land and property, high crime and insecurity, imminent risk of political violence and revolution – it was a familiar Third World equation.

Gabriella invited me in to meet her husband Hugo, and their two small children. Hugo told me he had invested some money in a cigar-making concern, a factory dating back to the turn of the century. ‘Paraguayan tobacco is good – not as good as Cuban, but close. We use Javan leaf for the wrappers, the rest is all local product.’ How much did the local cigars cost? I asked. I had seen none on sale anywhere. ‘That is because they are too expensive for most Paraguayans to buy now,’ he replied. ‘About US$2 each.’ Cigarettes cost US$7 a carton of 200 even in my local supermarket. I assumed the smuggled items, or false brands were even cheaper. Paraguayan men were ferocious smokers. The local brands I had seen advertised promised exotic pleasures. There was ‘Boots’ (not, alas, ‘Old Boots’) featuring a US style cowboy. There was ‘Palermo’ (a wealthy suburb of Buenos Aires, as well as a city in Sicily). The slogan for Palermo was Paraguayo y con orgullo’ – ‘Paraguayan and with pride’. The poster showed a racing car, and a racing driver, fag in hand. Then there was ‘Derby Club’ a contentious blend, much copied, imitated, falsified and smuggled, a favourite of the contrabanders trade, according to press reports. Truck-loads of ‘Derby Club’ were frequently discovered crossing the Brazilian border, without the required tax stamps on them. There was also ‘York’ and ‘US Mild’. In the local whisky line I particularly liked ‘Olde Monke’ and ‘Gran Cancellor’. Close inspection of the labels of the locally manufactured whiskies indicated that they had been made from a base of sugar cane – in fact were really rum dressed up as whisky. The local rum, called caña, was a working-class peasant tipple with macho associations. Alcoholism among the peasants and Indians was a serious problem; drunken all-male rum sessions often ended in knife fights and death, 80% of all killings in Paraguay were caused by armas blancas – knives or machetes.

Hugo was a fan of Paraguayan dolce far niente. ‘You cannot imagine how pleasant it is, Robert, for a man just to lie back in a hammock in the garden with a cigar all afternoon, just looking up at the clouds passing in the sky.’ While your wife and the maid do all the work, I thought, but did not say. The work ethic appeared to have scant appeal to Paraguayan men. All across the city they were sitting, sprawling, lounging or completely prone, in a state somewhere between sleep and coma. What little work was being done seemed to be entirely by women, who looked as if they monopolized about 95% of all available energy – men slumped, women bustled. Hugo invited me to visit his cigar factory. ‘You can buy the cigars at the special reduced employees price,’ he told me. Like most other promises I was made in Paraguay this invitation came to nothing. Despite several requests neither the visit nor the cigars materialized. Did they exist? Was the whole thing a fantasy? Perhaps he just did spend all his days in a hammock, gazing up at the sky. More concretely, Gabriella cooked macaroni cheese for supper, which I shared with them, along with a bottle of Argentine red wine called ‘Borgoña’, which tasted nothing like Burgundy. ‘Believe no one in Paraguay,’ Gabriella had told me, ‘believe nothing you cannot see or touch – this is a land of make-believe and fantasy – of chantar.’

I walked back to the Gran Hotel through the warm, velvety, shadow-strewn tropical night, the scents of the flowers and shrubs rising from the gardens around me along my way. Above hung the Southern Cross, that constellation which reaffirms that one is truly in the Southern Hemisphere. The petrol station at the crossroads at Avenida España was still open, and a lone soldier, the night shift, stood on duty, rifle at the ready, guarding the pumps. I turned off down a side lane, and walked a hundred yards away from the main road, the wine and the soft air having relaxed me. It was a mistake. The lane became dark, the surface under my feet was pitted and potholed. From a group sitting under a clump of trees a hundred yards further on, a man rose and lurched towards me. I was coming from the light of the main road and would be silhouetted clearly. He started to shout incoherently, angrily, at me, stumbling as he tried to run towards me. Out of the shadows I saw he had a machete, which he waved at me from above his head.

I turned abruptly, and made a fast trot back the way I had come, back towards the main road, and the petrol station with the lone soldier. I could hear the drunk behind me yelling and shouting at me now in incomprehensible Guarani. The lights of the main road grew nearer. I put on speed. I was sweating now, from the heat of the night and from fear. I was running. I could hear the man behind me, still coming on after me. If I slipped and fell, I would be done for. I ran really fast, faster than I had run for years. I got a sharp stitch in my side. I gasped for breath. Still I could hear the drunk lumbering behind me, breathing hard. The petrol station came in sight, well-lit, the soldier standing at ease, leaning on his rifle. I turned. The man was behind me, in shadow: he had stopped. He had seen the soldier, too. To chase a man at night in the streets of Asunción, waving a machete, was an invitation to be shot dead by anyone in uniform. The drunk mouthed angrily at me, but in silence, waving his weapon over his head, but he didn’t come on any further. Now would be the time to shoot him, I thought, if I had a gun. But then, of course, the soldier would shoot me. The drunk took a swig of rum from the bottle which he still held in his other hand, swallowed, and then spat at me silently, in disgust. I turned back and ran on, more slowly. In a moment I was under the arc of light by the petrol station forecourt, a recent model BMW being filled up by the uniformed attendant, a European-looking man in an expensive suit sitting at the wheel. I paused, slowing to a walk, and caught my breath. I turned to see what my pursuer was up to. He had completely vanished, swallowed up in the shadows behind me, invisible. I walked slowly back to the Gran Hotel now, keeping in light the whole way, my chest heaving. The margin between safety and danger in Asunción was just a few yards.

In spite of the tight-meshed flyscreen covering the windows of my room, some insects always managed to get inside. Tonight was no exception. On my pillow was a magnificent golden and black bug, crawling slowly about, lost on the great white pasture of cotton. I put this intruder in a matchbox carefully, so as not to damage it, and ejected it into the night. I felt a humanist European completely out of place in the teeming South American interior.

Breakfast was a buffet served in the grand ballroom, its ceiling painted with frescos of tropical birds and foliage, 19th century in style and execution. Sicilian painters had been imported by Madame Lynch, I was told, to carry out this work. It would take a sophisticated, European sensibility like Eliza Lynch’s to think of reproducing what was just outside the ballroom – tropical foliage and birds – inside the ballroom, on the ceiling. It was an artifice of nature present a few feet away outside: only to an émigré European’s eyes would such a ceiling decoration seem exotic. Madame Lynch was the first person in the post-colonial era to see the immense possibilities of Paraguay. To Francisco Solano López, her lover and protector, she promoted the idea of the country as a place to improve, to embellish, to make chic and elegant. No one had conceived of Paraguay in this way before, it had simply been a colony to exploit. Under her influence all the imposing buildings, self-consciously imperial, were begun – the opera house based on La Scala, Milan, the copy of Les Invalides, the huge Presidential Palace, the tropical Gothic railway station. Most of them were never finished – she and López were people in a hurry, new people, on the rise, imitating that tornado of newness, Napoleon Bonaparte, patron saint of all pushy, power-hungry arrivistes who have decided to live by will power and naked force. Napoleon had proved you could do it all, come from nowhere – Corsica, to be precise – seize power with a whiff of grapeshot, eliminate your rivals, rule by sheer energy and dash, conjure an empire out of thin air, become a king maker and breaker, institute an aristocracy of merit and favour, these all new people who had more energy and more to lose than the old aristocracy of blood. And you could do it all in a few years, if you drove people hard enough. Stucco was made for this style of rule. It looked like marble, or stone, or whatever you wanted to have it look like. And it went up so quickly – you just laid mudbricks or rubble walls, and then coated it and smoothed it down and painted it – presto! It looked just like ancient Rome. Peter the Great, another imperial arriviste, had used stucco to create his own fantasy of European civic grandeur, St Petersburg: take a dash of Venice, a draught of Amsterdam, add some London, and some Rome – and there you have it. In a few years, with enough slave labour and a few second-rate European architects – for who outside Russia has ever heard of Rastrelli, Hamilton or any other of Peter’s experts – you had a brand new ‘European’ capital on the Gulf of Finland.

Against all the odds the adventurer Napoleon III had actually erected another ramshackle empire in France, a country that had completely lost its way after the revolution of 1789, which would try all and every system of government, one after the other, in case one might actually work for more than a few years. Solano López had been immensely impressed with the Second Empire in France, which he had seen for himself on his European Grand Tour: Madame Lynch was a product of its frenetic decadence, its squalid energy, its sense of nervous excess and self-conscious cultivation – the bombastic new opera houses, the Baron Haussmann-designed avenues in Paris, the braying brass bands and the opulent uniforms of army officers; and the Zouaves, that orientalist military fantasy in baggy pantaloons, floppy fezzes and curled-up slippers – a corps just made for Verdi opera, harking back to Napoleon I’s Mamelukes from Egypt. All this López admired deeply and tried to imitate in Paraguay, where he could. If there were not enough men to enslave to build his new palace, well then, he would use child slave labour. To see what López and Lynch had in mind for Asunción it is only necessary to go to the spa town of Vichy, in France, for here Napoleon III, with his foreign architects, many of them English, created an eclectic, imperial yet Ruritanian pleasure-capital, small but with the flamboyance and grandeur of a capital city, right in the middle of nowhere, well away from cities such as Paris with revolutionary mobs. If López and Lynch had simply stuck to Paraguay, forgoing the dreams of conquering Uruguay, Brazil and Argentina, they would have created a complete mid-19th-century tropical-Gothic version of Vichy, and very extraordinary it would have been, too. Imperial overreach on a massive scale meant nothing was ever completed. What does remain – the Parisian-style parks, the ruinous stucco palazzi, the defunct railway station – are impressive enough: no Grand Tour ever bore such strange fruit, so far from anywhere. There are doubters, of course. Alwyn Brodsky, the American biographer of Eliza Lynch, among others, claims that the Gran Hotel was never Madame Lynch’s country residence at all, that the whole story has been cooked up as a publicity stunt by the hotel’s owners. Hard facts on which everyone can agree were always in short supply in Paraguay; more or less everything was up for debate. There were versions of events, narratives, claims, counter claims, refutations. The outsider became embroiled in these arguments, willy-nilly. What one person told you the next would vehemently deny. Reality was slippery.

Madame Lynch was the mistress and éminence grise to Mariscal Francisco Solano López, the third of Paraguay’s dictators after his father Carlos Antonio López (el fiscal – the magistrate), and the founding father Dr Francia (el supremo – the supreme one). All of Paraguay’s dictators had earned soubriquets: Solano López had been el mariscal (the Marshal) and Stroessner was el rubio (the blond). If Oviedo ever came to power he would inevitably be el bonsai – people called him that already – unless it was el loco which he was called, too. Beyond simple description no one could agree about anything Madame Lynch had done. For the Colorados she was a national heroine, whereas the Radical Liberals saw in her a manipulative exploiter who bled Paraguay white, along with Solano López, whom they viewed as a criminal lunatic. Both of these ambiguous historical figures had been co-opted by Stroessner and his regime, and the cult of their heroism promoted assiduously. Madame Lynch’s remains had been brought back from Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris and buried in La Recoleta in Asunción. The man who had organized this transshipment, a Lebanese-Paraguayan, had profited from the occasion to import a large quantity of hashish in the coffin with the remains of Madama.

Often called ‘Irish’, Eliza Lynch claimed to have been born in County Cork of Ascendency, Protestant parentage, and educated in Paris. She was a woman of cultivation and taste, speaking French, Spanish and Guarani with fluency, and played the piano, sang and danced with distinction. She had attached herself to López in Paris when he had been Ambassador at large in Europe, arriving with a substantial entourage and ample funds, the first the independent Paraguay had sent across to Europe. López had made the Grand Tour through France, Italy, England and the Crimea, where he observed the war in progress. In France he collected Napoleonic uniforms for his army officers, and from England guns and steamships supplied by the London firm of Blyth Brothers, who were also to send out a stream of technicians to Paraguay which enabled López to build up his army, navy and arsenal quickly enough to take on the three other regional powers all at once, very nearly beating them. López and Lynch returned to Paraguay with a complete kit for DIY imperial splendour – Sèvres and Limoges china sets, a Pleyel piano, fabrics, sewing machines, books, pictures, manuals of etiquette and court ritual, ladies’ maids and dancing masters, curtains, furniture and antimacassars. López actually went as far as to have a golden crown designed and sent out from France, but it was intercepted at Buenos Aires, and he never managed to have himself crowned Francisco I – even though he was referred to as such in some outlying provinces of Paraguay. Considered a great beauty, Eliza Lynch was the first modern career-blonde to arrive from Europe in South America with a mission, and a protector with enough money and political clout to make her ascent possible. Eva Perón, native-born South American, trod very much in the footsteps of Madame Lynch. Both of them were reputed to have been common whores working in brothels in their youth.

Madame Lynch created a sensation among the Guarani Indians, to whom she seemed an embodiment of the Virgin Mary. To the Creole elite of old Spanish blood she was an interloper, and a putana – a whore. They refused to recognize her, and eventually, when López got into his stride, were exterminated for their pains. López already had a wife and children established before he left for Europe and the new, big ideas he imbibed over there. Madama, as Lynch became known, was set up in style by López in Asunción, and formed her own alternative Court in her houses, which she decorated and furnished in the latest Parisian style. She was the cynosure of wit, elegance and art in a backward provincial capital that was nothing more than a village by a clearing in the jungle on the river. She came into her own when López senior died and Francisco Solano took over supreme power. López and Lynch turned the Pygmalion story upside down – Dr Higgins the rustic hayseed instructed by the sophisticated Parisienne Eliza Doolittle. Paraguay has always been, it would seem, a country of strong, capable women and weak, vain, indolent, incapable men. Whatever small quantity of sense Solano López may ever have had seems to have been provided by his mistress, though her detractors claim that it was her evil genius which spurred him on in his disastrous military and imperial ventures. The idea of becoming Emperor of Paraguay was not particularly absurd; there were in existence two new-minted empires – Brazil and France – as well as the older Russian, British, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish imperia. The fall of Napoleon III’s empire saw the creation of a German empire to replace it. Nor was defeating Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil particularly ambitious. They were all weak, poorly led and disorganized. The problem was that Solano López was consumed with vanity and egotism, trusted no one, and set about killing off his family and anyone in Paraguay of any ability and competence. Had he done nothing, and let his generals, British technical experts and brave soldiers simply attack the enemy, there is little doubt he would have defeated them and become Emperor of southern South America.

What is not in doubt is that Madame Lynch introduced into Paraguay an element of courtly style, of elegance, of well-dressed chic which had never been seen before, and which among the upper classes, survives and flourishes to this day. Paraguay, under her aegis, became a place of masked balls, river-boat picnics with brass bands in attendance, elaborate full-dress evening dances, classical music concerts, theatrical and opera performances, and champagne suppers. Everything had to be shipped up the river, and before that across the Atlantic from France, but neither time nor distance was any hindrance to the dandies and belles of either the 18th or 19th centuries. The details of all the wine imported by Thomas Jefferson from Château Margaux to his estate in Virginia still exist today in the Bordeaux archives. The Madame Lynch belle-of-the ball legacy lives on vibrantly today, and one of the startling features which elevates Paraguay from, say, the Congo, which in other ways it closely resembles, is the old-fashioned chic and elegance of the rich in Asunción, who still dress in long white gowns, full evening dress, starched shirts and tailcoats, and attend high-society balls with bands, masters of ceremony, sprung ballroom floors and all the other appurtenances of courtly behaviour now more or less a memory in Europe. The Society pages of Ultima Hora revealed a social Asunción which looked like Paris before the First War – pearls, tiaras, wing-collars, black or white tie, patent leather shoes, full orchestras in uniform – all a thousand miles up the river and in the sub-tropical jungle. At the Gran Hotel I was witness to all this, for every weekend some celebration would be mounted in the ballroom: Strauss waltzes would echo from the Indian orchestra in dress uniform, and the belles of Asunción would trip the light fantastic while outside waiters in white-starched uniforms with cummerbunds would circulate with canapes and champagne on silver trays held high over their heads. The debutante balls of the season were all lovingly photographed and reported in the Society pages, everyone’s name printed in full; it made light relief after the litanies of crime, corruption and bankruptcy on all the other pages.

Asunción’s bizarre elite were really too much. In a city where so many were almost starving there were no less than four Tiffany’s jewellery shops, and the company was doing so well that they could afford to take out full-page advertisements in the papers promoting their latest imported deluxe items from New York. Whether she had or had not lived in the old estancia that had become the Gran Hotel, all this was certainly the result of Eliza Lynch’s meteoric passage through Paraguay. Without doubt she and López and their Court would have danced here, for it would have been one of the few ballrooms in the city of that time able to accommodate large parties. It was somehow very Paraguayan to have breakfast under an artificial, painted tropical sky, installed by emigre Sicilians, when outside through the open french windows real Paraguayan tropical birds sat in real tropical foliage, fed from time to time by indigenous Guarani servants. I was reminded of the old Chinese saying: ‘Is Chuang-zu dreaming of the butterfly, or is the butterfly dreaming of Chuang-zu?’