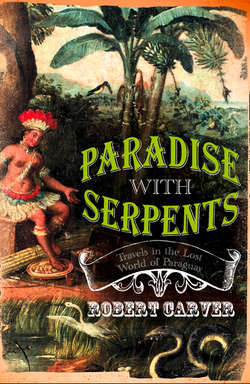

Читать книгу Paradise With Serpents: Travels in the Lost World of Paraguay - Robert Carver - Страница 11

Two An Ambassador is Born

ОглавлениеAt Sao Paulo airport the passengers in the transit lounge slumped forward like the dead, eyes shut, their heads resting downwards, caught in metal and canvas cradles, motionless, their arms hanging limply beside them. Above, around, and all over them hovered lean, lithe, intense young girls dressed in white t-shirts and jeans, with bare suntanned midriffs, their fingers, fists and elbows kneading their clients’ skulls, backs, shoulders, torsos and feet. This service, unlocking flight-tautened muscles and imparting spiritual calm, cost five US dollars, and took place in full view of everyone; a whole line of these modern penitents were slumped as if in prayer between the coffee stall and the newspaper stand. The newspapers and magazines on sale were all from the Americas – from all over Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, Bolivia and Venezuela, as well as Mexico and the US. There was nothing from Europe – and nothing, of course, from Paraguay: sometimes known optimistically as the Switzerland of the continent, it was more like the Tibet. You could get no information on the place anywhere. I was in a new continent, a new hemisphere, and a New World – and one in which my destination was as invisible as it had been in England.

The transit passengers, mostly Brazilians waiting for internal flights, whether upright, prone or at all angles between, were uniformly young, elegant and beautifully dressed. Wasp-waisted black men, ranging from double espresso to palest café au lait, drifted past me dressed in impossibly stylish suits of pastel hues. They were shod in elegant patent shoes which looked like Milan goes Carnival in Rio. There was a calm, almost Zen atmosphere to this hyper-modern airport, hi-tech tranquillity, luxe, calme and volupté. By definition, only the richest could afford to fly in this huge but deeply divided society. The chaos, the colour, the poverty of the favelas was nowhere in evidence. Problems? What problems? you might ask yourself. But the newspapers reminded you every time you glanced at their headlines. Argentina, Brazil, much of South America was in deep crisis. Argentina had withdrawn from its commitment to value the peso on par with the dollar. Foreign currency reserves had vanished in unexplained circumstances. The banks had shut their doors. Now outside the angry protesters, already known as los ahorristas, hammered at the roller-shutter doors with sticks and batons, while the police looked on sympathetically – they too had lost their savings: this was a middle-class and middle-aged protest. They wanted their money back. They had trusted their government but their government had, in effect, stolen their money, promising to honour an exchange rate, then reneging, then closing the banks by fiat, refusing to allow savers access to their own money. Who would ever trust their money to an Argentine bank again? How could you run any sort of economy when the banks were untrustworthy and closed the doors on their own customers? Argentina could not, would not service its international debts. It had borrowed and borrowed and borrowed, but the money had all been stolen or wasted. No new loans could be negotiated until the country agreed to start repaying the interest on its old loans. There were already food shortages, medical supplies running out, layoffs and bankruptcies. Kidnapping and gunlaw had proliferated. The demonstrations in the streets against the government were turning ugly. One of the richest – in theory at least – countries in the world was behaving like one of the poorest. In Brazil the situation teetered on the edge of crisis. And what of Paraguay? It was hard to find anything out about that secretive and isolated country. I would simply have to go and find out for myself.

Initially, I had favoured the classic approach into the country – via Argentina – to Buenos Aires, and up the River Plate and River Paraguay to Asunción. It was the route everyone had always taken from the first Spanish conquistadors to the exiled Argentine President Perón. But the old Mihailovich steamers had passed out of service, and Paraguay itself had started to look away from Argentina, from the south and its past, instead looking east to Brazil, and north to Miami and the USA. So I decided to fly to Asunción via Sao Paulo. There was another reason, apart from chaos, that I did not want to go via Argentina. It is no secret that the relations between Paraguay and Argentina have always been poor. Every Argentine I had met in London – and I had met dozens of them – had expressed a low opinion of Paraguay and Paraguayans. I was not going to get any helpful information from such entrenched and biased enemies of the country I wanted to explore. They seemed to regard the Paraguayans as backward natives, Indians in tents, almost savages. Their contempt was palpable.

From time to time, from the tannoy, a soft, sibilant voice would whisper departures in Brazilian-accented Portuguese to destinations from a poet’s lexicon – Manaos and Rio de Janeiro, Bahia de San Salvador and Cartagena de las Indias, Valparaiso and Tegucigalpa. However, there was just one flight to Paraguay and I would have to wait six hours for it. I found the departure gate and read the notice posted in front of it in Spanish, Portuguese and English: ‘Passengers are advised that all revolvers, automatics, rifles and other firearms must be unloaded with ammunition and packed inside luggage that has been checked in. No person carrying loaded or unloaded weapons will be allowed on to the plane. Thank you for your co-operation.’

With a sinking heart I realized that this was an official indication of what I had been warned of before – that Paraguayans have a love affair with powder and shot, pistol and lead, that knows no bounds. ‘Do they all carry pistols?’ I had asked a seasoned old Paraguay hand in London. ‘Well, I wouldn’t say all – no, not by a long chalk. However, it is fairly common. I mean, there are shootings all the time – I mean every day, everywhere. And knife fights, of course. It’s as well to be very polite to people. That generally pays off. Unless they want to kill you, in which case no amount of politeness would help.’ This was useful advice, I suppose: I had made a mental note to be more than usually polite. In the event, there might have been some Paraguayans I met during my eventful trip who were not armed with some sort of pistol, sub-machine gun, machete or knife, but I couldn’t actually swear to it. Often we find ourselves the embarrassed witness of other people’s intimate little moments when they think they are not being observed – the surreptitious scratch of the groin, the furtive pick of the nose, the fart eased out apparently unnoticed. In Paraguay these moments always revolved around someone’s jacket falling open to reveal a gleaming or matt-black automatic peeping out coyly from waistband or shoulder holster; a drawer opened by mistake to display a cluster of Uzi sub-machine guns, a brace of pump-action sawn-off shotguns, or a vintage Luger with an embossed swastika on the wooden handle. As tea is to China, chocolate to Switzerland or red wine to France, so are firearms to Paraguay.

The first group of Paraguayans I saw, clearly waiting for the same flight as myself, were obviously vaqueros or gauchos – cowboys in jeans and stetson hats, sprawled on the bench seats near the departure gate. Each of them had a tan cowhide grip out of which protruded the butts of their rifles. They all wore empty leather pistol holsters and belts with empty bullet holders. They had obviously read the same notice I had and would check their luggage in when the counter opened. I was tempted to go and talk to them, but didn’t. They looked tired, many of them actually kept falling asleep. They had clearly driven a herd of cattle across the border from Paraguay to Brazil, and were now returning home the quickest way possible. They would have sold their horses along with the cattle – it would make no sense to ride them back. Besides a certain natural diffidence in pushing myself forward into such an uncompromising bunch, there was a question of language. If the word ‘Indian’ did not convey political incorrectness, one would have said these were Indians. They had coppery skins and hooked noses, dark lank hair and tight, compact bodies. They were cholos, campesinos or indigenos, though, that was what one called them. Indio was considered by many a term of abuse and never used politely, though the first morning I walked through the central square in Asunción a very drunk man approached me from the favela below the Presidential Palace, cackling and swaying – ‘Yo soy indio, señor,’ he shouted at me. It was 7.30am and he was well away.

There was also the question of what language one should use in speaking to people. Graham Greene, who had visited Paraguay in the depths of the Stroessner dictatorship, had been warned that if he spoke in Spanish in the countryside, he might be assumed to be being patronizing and so run the risk of being shot. On the other hand, if he spoke Guarani, the language of the predominant ethnic group, he might be assumed to be insulting, considering them to be low, ignorant fellows. There was a third lingo, too, called Jalape, which was a mixture of Spanish and Guarani, just to make things clear as mud. I asked my Paraguay expert in London about this. ‘Well, you could always try speaking to them in English – that wouldn’t cause any offence. Not that they’d understand you, of course. In the Chaco the locals speak a version of 17th-century plattdeutsch. They learnt it from the Mennonites who farm out there. So you can find this chappie who knows where the alcalde’s office is but the only language he can give you instructions in is his own tribal palaver and 17th-century Low German. I suppose you speak that fluently, of course?’ I mumbled something about French and Italian. ‘Well, those won’t be much use. The other Germans, the Third Reich lot, don’t actually say “Heil Hitler” any more, but rather “Grüss Gott”. You could manage that, I suppose?’ Surely now that Stroessner, the half-Guarani, half-Bavarian dictator who had had a signed photograph of Hitler in his office and wore a pair of Goering’s boots, had been expelled from the country, things were rather better? ‘Rather worse, if anything. He ran a tight ship, did Don Alfredo. If you were a communist he had your balls cut off with a chainsaw to the sound of Guarani harp music. But if you were white, reasonably prosperous looking and apolitical he gave you no grief. Asunción in those days was a frightened town but a safe one. Now it’s frightened and very unsafe. No one is really in charge, no one has been paid for months, in some cases for years. Tempers are short, so is cash, and with the poor even food. In the last year things have gone downhill badly. There’s talk of a coup in the offing – or a revolution. Keep your head down is my advice.’ Advice I fervently hoped I was going to be able to keep.

The flight was all but empty. I had been earnestly quizzed by the security staff about my armoury. Was I certain I didn’t have any little amuse-gueules tucked away in my boots, sleeves, or hat? No little derringer pistols, ladies’ handguns, odd trifles I might in my haste have forgotten? No plastic guns, like the Glock, which wouldn’t have shown up in the X-ray machine? We were all frisked and turned over, very politely, three times before we were allowed on board. The group of cowboys sat at the front and got merry on beer. I sat at the back and concentrated on Argentine red wine. The plane went on afterwards to Cordoba in Argentina – Paraguay was just an embarrassing little stop to be got over as quickly as possible. The flight seemed very quick. Before I knew it we were banking over the river, below us a tropical city of low-rise redroofed houses, much dark green foliage, and a few taller buildings in the centre. My stomach knotted up tightly. Why on earth was I going into one of the most dangerous countries on Earth? I let the cowboys – indeed let all the other passengers – get off first, then I ambled slowly in late-afternoon tropical heat across the tarmac. The airport building was shabby concrete, low and small. You walked to the terminal on foot. I had had to fill in an old-fashioned white immigration card, exactly the same size and type as I’d filled in as a child in colonial Cyprus. ‘I’ve flown back into the 1950s,’ I thought, as I made for the Customs Hall.

Inside, under a high ceiling, a strange scene was being enacted. Several passengers with open suitcases were in deep argument with uniformed Customs officials. Between them were being passed a collection of automatics, pistols, rifles, sub-machine guns and boxes of ammunition that had clearly come out of the luggage. They were arguing, politely but forcefully about how much duty should be paid on these items. All the Customs men were engaged in this task. I kept walking.

A young woman in a smart uniform darted forward and smiled at me. ‘¿Diplomatico?’ she asked.

This threw me. ‘Yo soy inglés,’ I stammered.

‘¡Bravo!’ she said. ‘¡Bravo – el embajador británico!’ even more loudly, and started to applaud me, clapping her hands. The Customs men looked up at me from their deliberations, and gave me great big smiles. Unnervingly, they and their clients with the weaponry all started to applaud me, clapping their hands and calling out. ‘¡Bravo … ! ¡Bravo! ¡El embajador británico!’ I had only a small bag on wheels: I bowed to the left and to the right of me, and gave what I thought might pass as an ambassadorial benediction with my free hand, and kept on my way.

Another man stepped forward, took my immigration card, stamped my passport, and gave me a smart salute. ‘Any firearms, Your Excellency?’ he asked in Spanish.

‘No, señor, nada de nada,’ I replied. ‘Pasar, pasar, Excelencia,’ he said, motioning me with his hand. I moved out into the arrivals hall, which was already all but empty. I was in Paraguay, reborn as an ambassador. I kept walking until I saw the aseos [toilets], and then darted in. I was now in a muck sweat, and it wasn’t the heat. I had arrived all right, but what the hell had I got myself into?

The queue at the Cambio was short but the wait interminable. In front of me was a young North American banker and his girlfriend, here on business. ‘She speaks German so we should be OK,’ he told me. We exchanged cards. They were staying at Madame Lynch’s old estancia, now the best hotel in Asunción. Eliza Lynch is one of the few people connected with Paraguay known to the outside world. She was the mistress and éminence grise of the mid-nineteenth-century dictator López, who ruined the country with his insane war against Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay all at the same time.

When my turn came I asked the cashier behind the counter to change US$100 into guarani. He look at me as if I was crazy. ‘You want to change all of this into guaranis?’ His expression told me that whatever else Paraguay was going to be it was not going to be expensive. My glance fell lightly on the automatic pistol in a shoulder holster under his arm, and a large revolver he was using as a paperweight to hold down mounds of ancient and dirty bank notes from being blown all over the place by the fan. My eyes slid, unavoidably, to the security guard who was sitting on a chair, the chair high on a desk, at the far end of the room. He was in uniform and had a bazooka on his shoulder. It was pointed straight at me. There was a heavy metal grill between me and the man counting and re-counting hundreds of thousands of guarani notes, but the bazooka and the man’s stare made it hard for me to concentrate on the transaction. I did have the wit to ask for one of the ten thousand notes to be broken down into thousands. I hate the airport taxi rip-off, and always get the bus into town if there is one. I knew already the bus driver wouldn’t be able to change a thousand guarani note. The man with the bazooka wasn’t South American theatricals, I later discovered. The current method of bank robbery in Paraguay and Brazil was with an armoured car; these military vehicles simply ploughed into the banks and smashed through whatever bars were there. Bitter experience had taught the Paraguayans that a man with an antitank weapon was the only way of stopping these heists. Every bank I went into had one of these characters, as well as the run-of-the-mill fellows with sub-machine guns, pistols and grenades. Bank robberies were as common as thunderstorms and as violent. One of the current scandals in the papers, I discovered, was the use of a Paraguayan army armoured car in a bank robbery just across the border in Brazil. The Minister of Defence and the President were accused of having rented out the armoured car to the mob who carried out the raid, in return for a share of the proceeds. The Brazilians claimed they had photos of the armoured car during the raid, and then afterwards, back in its army park in Paraguay. They claimed US$15 million had been stolen, but the Paraguayan press claimed this was an exaggeration – more like $8 million, they thought. When asked why he robbed banks, Butch Cassidy had replied: ‘It’s where they keep the money.’ He had been gunned down in Bolivia, eventually, just next door to Paraguay.

I evaded the lurking taxi-drivers who I knew might cheat – and possibly rob me – and walked out to the bus stop. A couple of obviously quite poor locals were waiting for the bus into town. They eyed me cautiously, but then looked away. A more hopeful fellow carried a briefcase, wore a smart watch and had a shirt with a tie. I fell into conversation with him, and explained I was new to the country – did one buy a ticket on the bus, from a driver, or from a kiosk? He was helpful and informative and I was pleased to discover that I understood his Spanish and he understood mine. The bus arrived, empty, and my new friend helped me get my ticket. We sat together, and I asked him about the state of things as we rolled towards town.

Luis Gonzalves was a Customs official, just coming off duty. Mercifully he had missed my apotheosis as fake ambassador. He gave me a thorough rundown on everything. Things were very bad. Fifteen banks had gone bust taking almost everyone’s savings with them. The government was both weak and deeply corrupt. You could trust neither the police nor the army – both were corrupt and criminal. Civil servants hadn’t been paid for six months, some not for a year. The police hadn’t been paid for three months, and if they weren’t paid soon there would be a revolution. Foreigners were leaving the country in droves – every plane out was packed to capacity, every plane in virtually empty. The only people making money were the cocaleros who exported cocaine, and the mafia who stole from everyone. What about crime? Very bad, he said, and getting worse. Buses held up and the passengers robbed, even in central Asunción, every day. Shootings and kidnappings. Bank robberies and stick-ups. Everyone was sick of it. Many wished Stroessner was back in power. ‘That was a paradise then, but we didn’t know it,’ he said, a view I heard echoed by almost everyone I met. No one I spoke to stood up for what passed for ‘democracy’ in Paraguay.

As he talked and I plied him with questions I looked out through the window, intrigued by my first sight of Paraguay on the ground. The earth was deep, laterite ochre red, the road pitted and ancient tarmac. As we came closer to the centre of Asunción the gardens grew lusher with tropical foliage, glossy green, sometimes studded with bright flowers. There were fine stucco houses of an Italianate style with red tile roofs, though everywhere was an air of decay and dereliction. The cars were surprisingly modern and the traffic busy. My premonition at the money changer at the airport that the bus fare would be tiny was correct. The fare turned out to be 1,300 guarani – about 25 US cents. Luis had told me that a 5,000 guarani note was ‘too big’ to expect the driver to change for a ticket. In the end Luis had put in 100 guaranis of his own money for my ticket, as I had only two hundreds.

I asked Luis what he thought of the hotel I had selected. It was near the Plaza Independencia. He made a face. ‘Not good. A very bad area. Much crime, robberies, prostitution, drugs, alcoholics.’ I rapidly changed my plans. The Hotel Embajador met with slightly more approval. ‘A better area – near the business district.’ There’s nothing like local knowledge and a local warning. He was kind enough to get off the bus by the Embajador and show me where it was. We shook hands and he departed. Just before he left he said, ‘Oh, and by the way, tomorrow is the annual census. Everything will be shut – everything. Everyone has to be off the streets for the whole day. No buses run, no taxis, nothing.’ As we had been talking on the bus he had asked me casually ‘Which part of Brazil do you come from?’ I said, ‘I’m English. From England.’ He creased up his face as if in slight pain and waved his hand in front of his chest, ‘Ohh – so far away …’ First an ambassador, then a traveller from Brazil. Paraguay was very different to anywhere I had ever been before. It was quite simply one of the most remote countries in the world, about which almost no one knew anything, which almost no one went to, and almost no one came from – or indeed ever came back from. I felt heartened by this, but also daunted. I felt very much alone and friendless. If anything happened to me out here no one would know or care. Paraguay was a place in which one could disappear without trace.