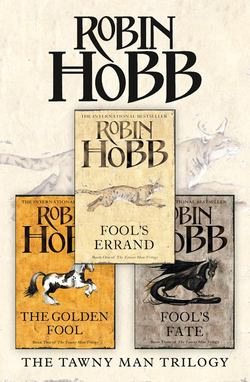

Читать книгу The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy: Fool’s Errand, The Golden Fool, Fool’s Fate - Робин Хобб - Страница 14

FIVE The Tawny Man

ОглавлениеThere is some indication, in the earliest accounts of the territories that eventually became the Six Duchies, that the Wit was not always a despised magic. These accounts are fragmentary, and the translations of these old scrolls are often disputed, but most of the master scribes will agree that at one time there were settlements where the preponderance of folk were born with the Wit and actively practised its magic. Some of these scrolls would indicate that these folk were the original inhabitants of the lands. This may be the source of the name that the Witted people apply to themselves: Old Blood.

In those times, the lands were not so settled. Folk relied more on hunting and the collecting of wild bounty than on harvesting what they had themselves planted. Perhaps in those days a bond between a man and a beast did not seem so uncanny, for folk provided for themselves much as the wild creatures did.

Even in more recent histories, accounts of Witted folk being slain for their magic are rare. Indeed, that these executions are recorded at all would seem to indicate that they were unusual, and hence noteworthy. It is not until after the brief reign of King Charger, the so-called ‘Piebald Prince’ that we find the Wit referred to with loathing and an assumption that its practice merits death. Following his reign, there are accounts of widespread slaughter of Witted folk. In some cases, entire villages were put to death. After that time of carnage, either those of Old Blood were rare, or too wary to admit that they carried the Wit-magic.

Beautiful summer days followed, one after another, like blue and green beads on a string. There was nothing wrong with my life. I worked in my garden, I finished the repairs to my long-neglected cottage, and in the early mornings and the summer twilight, I hunted with the wolf. I filled my days with good and simple things. The weather held fine. I had the warmth of the sun on my shoulders as I laboured, the swiftness of wind against my cheeks when I walked the sea cliffs in the evening, and the richness of the loamy earth in my garden. Peace but waited for me to give myself up to it. The fault was in me that I held back from it.

Some days, I was almost content. The garden grew well, the pea pods swelling fat, the beans racing up their trellis. There was meat to eat as well as some to set by, and daily the cottage became more snug and tidy. I took pride in what I accomplished. Yet sometimes I would find myself standing by Jinna’s charm in the garden, idly spinning the beads on it as I gazed towards the lane. Waiting. It was not so bad to wait for Hap to return when I was not so aware of waiting. But waiting for the boy’s return became an allegory for my whole life. When he did come back, what then? It was a question I had to ask myself. If he had succeeded, he would return only to leave again. It was what I should hope for. If he had not succeeded in earning his prentice fee, then I would have to rack my wits for another way to gain the money. And all the while, I would be waiting still. Waiting for Hap to return would transform itself into waiting for Hap to leave. Then what? Then … something more, my heart suggested, then it would be time for something more, but I could not put my finger on what stirred this restlessness in my soul. At the moments when I became conscious of that suspension, all of life chafed against me. Then the wolf would heave himself to his feet with a sigh and come to lean against me. A thrust of his muzzle would put his broad-skulled head under my hand.

Stop longing. You poison today’s ease, reaching always for tomorrow. The boy will come back when he comes back. What is there to grieve over in that? There is nothing wrong with either of us. Tomorrow will come soon enough, one way or another.

I knew he was right, and I would, usually, shake it off and go back to my chores. Once, I admit, I walked down to my bench overlooking the sea. But all I did was sit down on it and stare out across the water. I did not attempt to Skill. Perhaps, after all the years, I was finally learning that there was no comfort for loneliness in such reaching.

The weather continued fine, each morning a cool, fresh gift. Evenings, I reflected as I took slabs of fish from their hooks inside the smoker, were more precious than gifts. They were rest earned and tasks completed. They were satisfaction, when I let them be. The fish were done to my liking, a hard shiny red on the outside, but enough moisture left trapped within to keep a good flavour. I dropped the last slab into a net bag. There were already four such bags hanging from the rafters in the cottage. This would finish what I knew we needed for the winter. The wolf followed me inside and watched me climb up on the table to hang the fish. I spoke over my shoulder to him. ‘Shall we get up early tomorrow and go looking for a wild pig?’

I didn’t lose any wild pigs. Did you?

I looked down at him in surprise. It was a refusal, couched as humour, but a refusal all the same. I had expected wild enthusiasm. In truth, I myself had little appetite for such a strenuous hunt as a pig would demand. I had offered it to the wolf in the hopes of pleasing him. I had sensed a certain listlessness in him of late, and suspected that he mourned Hap’s absence. The boy had been a lively hunting companion for him. I feared that in comparison, I was rather dull. I know he felt my query as I gazed at him, but he had retreated into his own mind, leaving only a distracted haze of thoughts.

‘Are you well?’ I asked him anxiously.

He turned his head sharply towards the door. Someone comes.

‘Hap?’ I jumped down to the floor.

A horse.

I had left the door ajar. He went to it and peered out, ears pricked. I joined him. A moment passed, and then I heard the steady thudding of hoofbeats. Starling?

Not the howling bitch. He did not disguise his relief that it was not the minstrel. That stung a bit. Only recently had I fully realized how much he had disliked her. I said nothing aloud, nor did I form the thought towards him, but he knew. He cast me an apologetic glance, then ghosted out of the house.

I stepped out onto the porch and waited, listening. A good horse. Even at this time of day, there was life in its step. As horse and rider came into view, I took breath at the sight of the animal. The quality of her breeding shouted from her every line. She was white. Her snowy mane and tail flowed as if she had been groomed but moments before. Silky black tassels bound in her mane complemented the black and silver of her harness. She was not a large mare, but there was fire in the way she turned a knowing eye and a wary ear towards the invisible wolf that flanked her through the woods. She was alert without being afraid. She began to lift her hooves a bit higher, as if to assure Nighteyes that she had plenty of energy either to fight or flee.

The rider was fully worthy of the horse. He sat her well, and I sensed a man in harmony with his mount. His garments were black, trimmed in silver, as were his boots. It sounds a sombre combination, did not the silver run riot as embroidery round his summer cloak, and silver-edged white lace at his cuffs and throat. Silver bound his fair hair back from his high brow. Fine black gloves coated his hands like a second skin. He was a slender youth, but just as the lightness of his horse prompted one to think of swiftness, so did his slimness call to mind agility rather than fragility. His skin was a sun-kissed gold, as was his hair, and his features were fine. The tawny man approached silently save for the rhythmic striking of his horse’s hooves. When he drew near, he reined in his beast with a touch, and sat looking down on me with amber eyes. He smiled.

Something turned over in my heart.

I moistened my lips, but could find no words, nor breath to utter them if I had. My heart told me one thing, my eyes another. Slowly the smile faded from his face and his eyes. A still mask replaced it. When he spoke, his voice was low, his words emotionless. ‘Have you no greeting for me, Fitz?’

I opened my mouth, then helplessly spread wide my arms. At the gesture that said all I had no words for, an answering look lit his face. He glowed as if a light had been kindled in him. He did not dismount but flung himself from his horse towards me, a launch aided by Nighteyes’ sudden charge from the wood towards him. The horse snorted in alarm and crow-hopped. The Fool came free of his saddle with rather more energy than he had intended, but, agile as ever, he landed on the balls of his feet. The horse shied away, but none of us paid her any attention. In one step, I caught him up. I enfolded him in my arms as the wolf gambolled about us like a puppy.

‘Oh, Fool,’ I choked. ‘It cannot be you, yet it is. And I do not care how.’

He flung his arms around my neck. He hugged me fiercely, Burrich’s earring pressing cold against my neck. For a long instant, he clung to me like a woman, until the wolf insistently thrust himself between us. Then the Fool went down on one knee in the dust, careless of his fine clothes as he clasped the wolf about his neck. ‘Nighteyes!’ he whispered in savage satisfaction. ‘I had not thought to see you again. Well met, old friend.’ He buried his face in the wolf’s ruff, wiping away tears. I did not think less of him for them. My own ran unchecked down my face.

He flowed to his feet, every nuance of his grace as familiar to me as the drawing of breath. He cupped the back of my head and in his old way, pressed his brow to mine. His breath smelled of honey and apricot brandy. Had he fortified himself against this meeting? After a moment he drew back from me but kept a grip on my shoulders. He stared at me, his eyes touching the white streak in my hair and running familiarly over the scars on my face. I stared just as avidly, not just at how he had changed, his colouring gone from white to tawny, but at how he had not changed. He looked as callow a youth as when I had last seen him near fifteen years ago. No lines marred his face.

He cleared his throat. ‘Well. Will you ask me in?’ he demanded.

‘Of course. As soon as we’ve seen to your horse,’ I replied huskily.

The wide grin that lit his face erased all years and distance between us. ‘You’ve not changed a bit, Fitz. Horses first, as it ever was with you.’

‘Not changed?’ I shook my head at him. ‘You are the one who looks not a day older. But all else …’ I shook my head helplessly as I sidled towards his horse. She high-stepped away, maintaining the distance. ‘You’ve gone gold, Fool. And you dress as richly as Regal once did. When first I saw you, I did not know you.’

He gave a sigh of relief that was half a laugh. ‘Then it was not as I feared, that you were wary of welcoming me?’

Such a question did not even deserve an answer. I ignored it, advancing again on the horse. She turned her head, putting the reins just out of my reach. She kept the wolf in view. I could feel the Fool watching us with amusement. ‘Nighteyes, you are not helping and you know it!’ I exclaimed in annoyance. The wolf dropped his head and gave me a knowing glance, but he stopped his stalking.

I could put her in the barn myself if you but gave me the chance.

The Fool cocked his head slightly, regarding us both quizzically. I felt something from him; the thinnest knife-edge of shared awareness. I almost forgot the horse. Without volition, I touched the mark he had left upon me so long ago; the silver fingerprints on my wrist, long faded to a pale grey. He smiled again, and lifted one gloved hand, the finger extended towards me, as if he would renew that touch. ‘All down the years,’ he said, his voice going golden as his skin, ‘you have been with me, as close as the tips of my fingers, even when we were years and seas apart. Your being was like the hum of a plucked string at the edge of my hearing, or a scent carried on a breeze. Did not you feel it so?’

I took a breath, fearing my words would hurt him. ‘No,’ I said quietly. ‘I wish it had been so. Too often I felt myself completely alone save for Nighteyes. Too often I’ve sat at the cliff’s edge, reaching out to touch anyone, anywhere, yet never sensing that anyone reached back to me.’

He shook his head at that. ‘Had I possessed the Skill in truth, you would have known I was there. At your very fingertips, but mute.’

I felt an odd easing in my heart at his words, for no reason I could name. Then he made an odd sound, between a cluck and a chirrup, and the horse immediately came to him to nuzzle his outstretched hand. He passed her reins to me, knowing I was itching to handle her. ‘Take her. Ride her to the end of your lane and back. I’ll wager you’ve never ridden her like in your life.’

The moment her reins were in my hands, the mare came to me. She put her nose against my chest, and took my scent in and out of her flaring nostrils. Then she lifted her muzzle to my jaw and gave me a slight push, as if urging me to give in to the Fool’s temptation. ‘Do you know how long it has been since I was astride any kind of a horse?’ I asked them both.

‘Too long. Take her,’ he urged me. It was a boy’s thing to do, this immediate offering to share a prized possession, and my heart answered it, knowing that no matter how long or how far apart we had been, nothing important had changed between us.

I did not wait to be invited again. I set my foot to the stirrup and mounted her, and despite all the years, I could feel every difference there was between this mare and my old horse, Sooty. She was smaller, finer-boned, and narrower between my thighs. I felt clumsy and heavy-handed as I urged her forwards, then spun her about with a touch of the rein. I shifted my weight and took in the rein and she backed without hesitation. A foolish grin came over my face. ‘She could equal Buckkeep’s best when Burrich had the stables prime,’ I admitted to him. I set my hand to her withers, and felt the dancing flame of her eager little mind. There was no apprehension in her, only curiosity. The wolf sat on the porch watching me gravely.

‘Take her down the lane,’ the Fool urged me, his grin mirroring mine. ‘And give her a free head. Let her show you what she can do.’

‘What’s her name?’

‘Malta. I named her myself. I bought her in Shoaks, on my way here.’

I nodded to myself. In Shoaks, they bred their horses small and light for travelling their broad and windswept plains. She’d be an easy keeper, requiring little feed to keep her moving day after day. I leaned forwards slightly. ‘Malta,’ I said, and she heard permission in her name. She sprang forwards and we were off.

If her day’s journey to reach my cabin had wearied her, she did not show it. Rather it was as if she had grown restive with her steady pace and now relished the chance to stretch her muscles. We flowed beneath the overarching trees, and her hooves making music on the hard-packed earth woke a like song in my heart.

Where my lane met the road, I pulled her in. She was not even blowing; instead she arched her neck and gave the tiniest tug at her bit to let me know she would be glad to continue. I held her still, and looked both up and down the road. Odd, how that small change in perspective altered my whole sense of the world around me. Astride this fine animal, the road was like a ribbon unfurled before me. The day was fading, but even so I blinked in the gentling light, seeing possibilities in the blueing hills and the mountains edging into the evening horizon. The horse between my thighs brought the whole world closer to my door. I sat her quietly, and let my eyes travel a road that could eventually take me back to Buckkeep, or indeed to anywhere in the entire world. My quiet life in the cabin with Hap seemed as tight and confining as an outworn skin. I longed to writhe like a snake and cast it off, to emerge gleaming and new into a wider world.

Malta shook her head, mane and tassels flying, awakening me to how long I had sat and stared. The sun was kissing the horizon. The horse ventured a step or two against my firm rein. She had a will of her own, and was as willing to gallop down the road as to walk sedately back to my cabin. So we compromised; I turned her back up my lane, but let her set her own pace. This proved to be a rhythmic canter. When I pulled her in before my cabin, the Fool peered out the door at me. ‘I’ve put the kettle on,’ he called. ‘Bring in my saddle pack, would you? There’s Bingtown coffee in it.’

I stabled Malta beside the pony and gave her fresh water and such hay as I had. It was not much; the pony was an adept forager, and did not mind the scrubby pasturage on the hillside behind the cabin. The Fool’s sumptuous tack gleamed oddly against the rough walls. I slung his saddle pack over my shoulder. The summer dusk was thickening as I made my way back to my cabin. There were lights in the windows and the pleasant clatter of cooking pots. As I entered to set the packs on my table, the wolf was sprawled before the fire drying his damp fur and the Fool was stepping around him to set a kettle on the hook. I blinked my eyes, and for an instant I was back in the Fool’s hut in the Mountains, healing from my old injury while he stood between the world and me that I might rest. Then as now he created reality around himself, bringing order and peace to a small island of warm firelight and the simple smell of hearth-bread cooking.

He swung his pale eyes to meet mine, the gold of them mirroring the firelight. Light ran up his cheekbones and dwindled as it merged with his hair. I gave my head a small shake. ‘In the space of a sundown, you show me the wide world from a horse’s back, and the soul of the world within my own walls.’

‘Oh, my friend,’ he said quietly. No more than that needed to be said.

We are whole.

The Fool cocked his head to that thought. He looked like a man trying to recall something important. I shared a glance with the wolf. He was right. Like sundered pieces of crockery that snick back together so precisely that the crack becomes invisible, the Fool joined us and completed us. Whereas Chade’s visit had filled me with questions and needs, the Fool’s presence was in itself an answer and a satisfaction.

He had made free with my garden and my pantry. There were new potatoes and carrots and little purple-and-white turnips simmering in one pot. Fresh fish layered with basil steamed and rattled a tight-fitting lid. When I raised my brows to that, the Fool merely observed, ‘The wolf seems to recall my fondness for fresh fish.’ Nighteyes set his ears back and lolled his tongue out at me. Hearthcakes and blackberry preserves rounded out our simple meal. He had ferreted out my Sandsedge brandy. It waited on the table.

He dug through his pack and produced a cloth bag of dark beans shining with oil. ‘Smell this,’ he demanded, and then put me to crushing the beans while he filled my last available pot with water and set it to boil. There was little conversation. He hummed to himself and the fire crackled while pot lids tapped and occasional escaping drips steamed away on the fire. The pestle against the mortar made a homely sound as I ground the aromatic beans. We moved for a space in wolf time, in the contentment of the present, not worrying about what had passed or what was to come. That evening remains for me always a moment to cherish, as golden and fragrant as brandy in crystal glasses.

With a knack I’ve never attained, the Fool made all the food ready at once, so that the deep brown coffee steamed alongside the fish and the vegetables, while a stack of hearthcakes held their warmth under a clean cloth. We sat down to the table together, and the Fool set out a slab of the tender fish for the wolf, who dutifully ate it though he would have preferred it raw and cold. The cabin door stood open on a starry night; the fellowship of shared food on a pleasantly mild evening filled the house and overflowed.

We heaped the dirty dishes aside to deal with later, and took more coffee out onto the porch. It was my first experience of the foreign stuff. The hot brown liquid smelled better than it tasted, but sharpened the mind pleasantly. Somehow we ended up walking down to the stream together, our cups warm in our hands. The wolf drank long there of the cool water, and then we strolled back, to pause by the garden. The Fool spun the beads on Jinna’s charm as I told him the tale of it. He flicked the bell with a long fingertip, and a single silver chime spun spreading into the night. We visited his horse, and I shut the door on the chicken-house to keep the poultry safe for the night. We wandered back to the cabin and I sat down on the edge of the porch. Without a word, the Fool took my empty cup back into the house.

When he returned, Sandsedge brandy brimmed the cup. He sat down beside me on one side; the wolf claimed a place on the other side, and set his head on my knee. I took a sip of the brandy, silked the wolf’s ears through my fingers and waited. The Fool gave a small sigh. ‘I stayed away from you as long as I could.’ He offered the words like an apology.

I lifted an eyebrow to that. ‘Any time that you returned to visit me would not have been too soon. I often wondered what had become of you.’

He nodded gravely. ‘I stayed away, hoping that you would finally find a measure of peace and contentment.’

‘I did,’ I assured him. ‘I have.’

‘And now I have returned to take it away from you.’ He did not look at me as he said those words. He stared off into the night, at the darkness beneath the crowding trees. He swung his legs like a child, and then took a sip of his brandy.

My heart gave a little lurch. I had thought he had come to see me for my own sake. Carefully I asked, ‘Chade sent you then? To ask me to come back to Buckkeep? I already gave him my answer.’

‘Did you? Ah.’ He paused a moment, swirling the brandy in his cup as he pondered. ‘I should have known that he would have been here already. No, my friend, I have not seen Chade in all these years. But that he has already sought you out but proves what I already dreaded. A time is upon us when the White Prophet must once more employ his Catalyst. Believe me, if there were any other way, if I could leave you in peace, I would. Truly I would.’

‘What do you need of me?’ I asked him in a low voice. But he was no better at giving me a straight answer now than when he had been King Shrewd’s Fool and I was the King’s bastard grandson.

‘I need what I have always needed from you, ever since I discovered that you existed. If I am to change time in its course, if I am to set the world on a truer path than it has ever followed before, then I must have you. Your life is the wedge I use to make the future jump from its rut.’

He looked at my disgruntled face and laughed aloud at me. ‘I try, Fitz, indeed I do. I speak as plainly as I can, but your ears will not believe what they hear. I first came to the Six Duchies, and to Shrewd’s court all those years ago, to seek a way to fend off a disaster. I came not knowing how I would do it, only that I must. And what did I discover? You. A bastard, but nonetheless an heir to the Farseer line. In no future that I had glimpsed had I seen you, yet when I recalled all I knew of the prophecies of my kind, I discovered you, again and again. In sideways mentions and sly hints, there you were. And so I did all that I could to keep you alive, which mostly was bestirring you to keep yourself alive. I groped through the mists with no more than a snail’s glinting trail of prescience to guide me. I acted, based on what I knew I must prevent, rather than what I must cause. We cheated all those other futures. I urged you into danger and I dragged you back from death, heedless of what it cost you in pain and scars and dreams denied. Yet you survived, and when all the cataclysms of the Cleansing of Buck were done, there was a trueborn heir to the Farseer line. Because of you. And suddenly it was as if I were lifted onto a peak above a valley brimmed with fog. I do not say that my eyes can pierce the fog; only that I stand above it and see, in the vast distance, the peaks of a new and possible future. A future founded on you.’

He looked at me with golden eyes that seemed almost luminous in the dim light from the open door. He just looked at me, and I suddenly felt old and the arrow scar by my spine gave me a twist of pain that made me catch my breath for an instant. A throb like a dull red foreboding followed it. I told myself I had sat too long in one position; that was all.

‘Well?’ he prompted me. His eyes moved over my face almost hungrily.

‘I think I need more brandy,’ I confessed, for somehow my cup had become empty.

He drained his own cup and took mine. When he rose, the wolf and I did also. We followed him into the cabin. He rucked about in his pack and took out a bottle. It was about a quarter empty. I tucked the observation away in my mind; so he had fortified himself against this meeting. I wondered what part of it he had dreaded. He uncorked the bottle and refilled both our cups. My chair and Hap’s stool were by the hearth, but we ended up sitting on the hearthstones by the dying fire. With a heavy sigh the wolf stretched out between us, his head in my lap. I rubbed his head, and caught a sudden twinge of pain from him. I moved my hand down him to his hip joints and massaged them gently. Nighteyes gave a low groan as the touch eased him.

How bad is it?

Mind your own business.

You are my business.

Sharing pain doesn’t lessen it.

I’m not sure about that.

‘He’s getting old.’ The Fool interrupted our chained thoughts.

‘So am I,’ I pointed out. ‘You, however, look as young as ever.’

‘Yet I’m substantially older than both of you put together. And tonight I feel every one of my years.’ As if to give the lie to his own words, he lithely drew his knees up tight to his chest and rested his chin upon them as he hugged his own legs.

If you drank some willow bark tea, it might ease you.

Spare me your swill and keep rubbing.

A small smile bowed the Fool’s mouth. ‘I can almost hear you two. It’s like a gnat humming near my ear, or the itch of something forgotten. Or trying to recall the sweet taste of something from a passing whiff of its fragrance.’ His golden eyes suddenly met mine squarely. ‘It makes me feel lonely.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I said, not knowing what else I could say. That Nighteyes and I spoke as we did was not an effort to exclude him from our circle. It was that our circle made us one in a fundamental way we could not share.

Yet once we did, Nighteyes reminded me. Once we did, and it was good.

I do not think that I glanced at the Fool’s gloved hand. Perhaps he was closer to us than he realized, for he lifted his hand and tugged the finely-woven glove from it. His long-fingered, elegant hand emerged. Once, a chancing touch of his had brushed his fingers against Verity’s Skill-impregnated hands. That touch had silvered his fingers, and given him a tactile Skill that let him know the history of things simply by touching them. I turned my own wrist to look down at it. Dusky grey fingerprints still marked the inside of my wrist where he had touched me. For a time, our minds had been joined, almost as if he and Nighteyes and I were a true Skill coterie. But the silver on his fingers had faded, as had the fingerprints on my wrist and the link that had bonded us.

He lifted one slender finger as if in a warning. Then he turned his hand and extended his hand to me as if he proffered an invisible gift on those outstretched fingertips. I closed my eyes to steady myself against the temptation. I shook my head slowly. ‘It would not be wise,’ I said thickly.

‘And a Fool is supposed to be wise?’

‘You have always been the wisest creature I’ve known.’ I opened my eyes to his earnest gaze. ‘I want it as I want breath itself, Fool. Take it away, please.’

‘If you’re sure … no, that was a cruel question. Look, it is gone.’ He gloved the hand, held it up to show me and then clasped it with his naked one.

‘Thank you.’ I took a long sip of my brandy, and tasted a summer orchard and bees bumbling in the hot sunshine among the ripe and fallen fruit. Honey and apricots danced along the edges of my tongue. It was decadently good. ‘I’ve never tasted anything like this,’ I observed, glad to change the subject.

‘Ah, yes. I’m afraid I’ve spoiled myself, now that I can afford the best. There’s a good stock of it in Bingtown, awaiting a message from me to tell them where to ship it.’

I cocked my head at him, trying to find the jest in his words. Slowly it sank in that he was speaking the plain truth. The fine clothes, the blooded horse, exotic Bingtown coffee and now this … ‘You’re rich?’ I hazarded sagely.

‘The word doesn’t touch the reality.’ Pink suffused his amber cheeks. He looked almost chagrined to admit it.

‘Tell!’ I demanded, grinning at his good fortune.

He shook his head. ‘Far too long a tale. Let me condense it for you. Friends insisted on sharing with me a windfall of wealth. I doubt that even they knew the full value of all they pressed upon me. I’ve a friend in a trading town, far to the south, and as she sells it off for the best prices such rare goods can command, she sends me letters of credit to Bingtown.’ He shook his head ruefully, appalled at his good fortune. ‘No matter how well I spend it, there always seems to be more.’

‘I am glad for you,’ I said with heartfelt sincerity.

He smiled. ‘I knew you would be. Yet, the strangest part perhaps is that it changes nothing. Whether I sleep on spun gold or straw, my destiny remains the same. As does yours.’

So we were back to that again. I summoned all my strength and resolve. ‘No, Fool,’ I said firmly. ‘I won’t be pulled back into Buckkeep politics. I have a life of my own now, and it is here.’

He cocked his head at me, and a shadow of his old jester’s smile widened his lips. ‘Ah, Fitz, you’ve always had a life of your own. That is, precisely, your problem. You’ve always had a destiny. As for it being here …’ He shied a look around the room. ‘Here is no more than where you happen to be standing at the moment. Or sitting.’ He took a long breath. ‘I haven’t come to drag you back into anything, Fitz. Time has brought me here. It’s carried you here as well. Just as it brought Chade, and other twists to your fortunes of late. Am I wrong?’

He was not. The entire summer had been one large kink in my smoothly coiling life. I didn’t reply but I didn’t need to. He already knew the answer. He leaned back, stretching his long legs out before him. He nibbled at his ungloved thumb thoughtfully, then leaned his head back against the chair and closed his eyes.

‘I dreamed of you once,’ I said suddenly. I had not been planning to say the words.

He opened one cat-yellow eye. ‘I think we had this conversation before. A long time ago.’

‘No. This is different. I didn’t know it was you until just now. Or maybe I did.’ It had been a restless night, years ago, and when I awakened the dream had clung to my mind like pitch on my hands. I had known it was significant, and yet the snatch of what I had seen had made so little sense, I could not grasp its significance. ‘I didn’t know you had gone golden, you see. But now, when you leaned back with your eyes closed … You – or someone – were lying on a rough wooden floor. Your eyes were closed; you were sick or injured. A man leaned over you. I felt he wanted to hurt you. So I …’

I had repelled at him, using the Wit in a way I had not for years. A rough thrust of animal presence to shove him away, to express dominance of him in a way he could not understand, yet hated. The hatred was proportionate to his fear. The Fool was silent, waiting for me.

‘I pushed him away from you. He was angry, hating you, wanting to hurt you. But I pressed on his mind that he had to go and fetch help for you. He had to tell someone that you needed help. He resented what I did to him, but he had to obey me.’

‘Because you Skill-burned it into him,’ the Fool said quietly.

‘Perhaps,’ I admitted unwillingly. Certainly the next day had been one long torment of headache and Skill-hunger. The thought made me uneasy. I had been telling myself that I could not Skill that way. Certain other dreams stirred uneasily in my memory. I pushed them down again. No, I promised myself. They were not the same.

‘It was the deck of a ship,’ he said quietly. ‘And it’s quite likely you saved my life.’ He took a breath. ‘I thought something like that might have happened. It never made sense to me that he didn’t get rid of me when he could have. Sometimes, when I was most alone, I mocked myself that I could cling to such a hope. That I could believe I was so important to anyone that he would travel in his dreams to protect me.’

‘You should have known better than that,’ I said quietly.

‘Should I?’ The question was almost a challenge. He gave me the most direct look I had ever received from him. I did not understand the hurt I saw in his eyes, nor the hope. He needed something from me, but I wasn’t sure what it was. I tried to find something to say, but before I could, the moment seemed to pass. He looked away from me, releasing me from his plea. When his eyes came back to mine, he changed both his expression and the subject.

‘So. What happened to you after I flew away?’

The question took me aback. ‘I thought … but you said you had not seen Chade for years. How did you know how to find me, then?’

By way of answer, he closed his eyes, and then brought his left and right forefingers together to meet before him. He opened his eyes and smiled at me. I knew it was as much answer as I would get.

‘I scarcely know where to begin.’

‘I do. With more brandy.’

He flowed effortlessly to his feet. I let him take my empty cup. I set a hand on Nighteyes’ head and felt him hovering between sleep and wakefulness. If his hips still troubled him, he was concealing it well. He was getting better and better at holding himself apart from me. I wondered why he concealed his pain from me.

Do you wish to share your aching back with me? Leave me alone and stop borrowing trouble. Not every problem in the world belongs to you. He lifted his head from my knee and with a deep sigh stretched out more fully before the hearth. Like a curtain falling between us, he masked himself once more.

I rose slowly, one hand pressed against my back to still my own ache. The wolf was right. Sometimes there was little point to sharing pain. The Fool refilled both our cups with his apricot brandy. I sat down at the table and he set mine before me. His own he kept in his hand as he wandered about the room. He paused before Verity’s unfinished map of the Six Duchies on my wall, glanced into the nook that was Hap’s sleeping alcove and then leaned in the door of my bedchamber. When Hap had come to live with me, I had added an additional chamber that I referred to as my study. It had its own small hearth, as well as my desk and a scroll rack. The Fool paused at the door to it, then stepped boldly inside. I watched him. It was like watching a cat explore a strange house. He touched nothing, yet appeared to see everything. ‘A lot of scrolls,’ he observed from the other room.

I raised my voice to reach him. ‘I’ve been trying to write a history of the Six Duchies. It was something that Patience and Fedwren proposed years ago, back when I was a boy. It helps to occupy my time of an evening.’

‘I see. May I?’

I nodded. He seated himself at my desk, and unrolled the scroll on the stone game. ‘Ah, yes, I remember this.’

‘Chade wants it when I am finished with it. I’ve sent him things, from time to time, via Starling. But up until a month or so ago, I hadn’t seen him since we parted in the Mountains.’

‘Ah. But you had seen Starling.’ His back was to me. I wondered what expression he wore. The Fool and the minstrel had never got along well together. For a time, they had made an uneasy truce, but I had always been a bone of contention between them. The Fool had never approved of my friendship with Starling, had never believed she had my best interests at heart. That didn’t make it any easier to let him know he had always been right.

‘For a time, I saw Starling. On and off for, what, seven or eight years. She was the one who brought Hap to me about seven years ago. He’s just turned fifteen. He’s not home right now; he’s hired out in the hopes of gaining more coin for an apprenticeship fee. He wants to be a cabinetmaker. He does good work, for a lad; both the desk and the scroll rack are his work. Yet I don’t know if he has the patience for detail that a good joiner must have. Still, it’s what his heart is set on, and he wants to apprentice to a cabinetmaker in Buckkeep Town. Gindast is the joiner’s name, and he’s a master. Even I have heard of him. If I had realized Hap would set his heart so high, I’d have saved more over the years. But –’

‘Starling?’ His query reined me back from my musings on the boy.

It was hard to admit it. ‘She’s married now. I don’t know how long. The boy found it out when he went to Springfest at Buckkeep with her. He came home and told me.’ I shrugged one shoulder. ‘I had to end it between us. She knew I would when I found out. It still made her angry. She couldn’t understand why it couldn’t continue, as long as her husband never found out.’

‘That’s Starling.’ His voice was oddly non-judgemental, as if he commiserated with me over a garden blight. He turned in the chair to look at me over his shoulder. ‘And you’re all right?’

I cleared my throat. ‘I’ve kept busy. And not thought about it much.’

‘Because she felt no shame at all, you think it must all belong to you. People like her are so adept at passing on blame. This is a lovely red ink on this. Where did you get it?’

‘I made it.’

‘Did you?’ Curious as a child, he unstopped one of the ink bottles on my desk and stuck in his little finger. It came out tipped in scarlet. He regarded it for a moment. ‘I kept Burrich’s earring,’ he suddenly admitted. ‘I never took it to Molly.’

‘I see that. I’m just as glad you didn’t. It’s better that neither of them know I survived.’

‘Ah. Another question answered.’ He drew a snowy kerchief from inside his pocket and ruined it by wiping the red ink from his finger. ‘So. Are you going to tell me all the events in order, or must I pry bits out of you one at a time?’

I sighed. I dreaded recalling those times. Chade had been willing to accept an account of the events that related to the Farseer reign. The Fool would want more than that. Even as I cringed from it, I could not evade the notion that somehow I owed him that telling. ‘I’ll try. But I’m tired, and we’ve had too much brandy, and it’s far too much to tell in one evening.’

He tipped back in my chair. ‘Were you expecting me to leave tomorrow?’

‘I thought you might.’ I watched his face as I added, ‘I didn’t hope it.’

He accepted me at my word. ‘That’s good, then, for you would have hoped in vain. To bed with you, Fitz. I’ll take the boy’s cot. Tomorrow is soon enough to begin to fill in nearly fifteen years of absence.’

The Fool’s apricot brandy was more potent than the Sandsedge, or perhaps I was simply wearier than usual. I staggered to my room, dragged off my shirt and dropped into my bed. I lay there, the room rocking gently around me, and listened to his light footfalls as he moved about in the main room, extinguishing candles and pulling in the latch string. Perhaps only I could have seen the slight unsteadiness in his movements. Then he sat down in my chair and stretched his legs towards the fire. At his feet, the wolf groaned and shifted in his sleep. I touched minds gently with Nighteyes; he was deeply asleep and welling contentment.

I closed my eyes, but the room spun sickeningly. I opened them a crack and stared at the Fool. He sat very still as he stared into the fire, but the dancing light of the flames lent their motion to his features. The angles of his face were hidden and then revealed as the shadows shifted. The gold of his skin and eyes seemed a trick of the firelight, but I knew they were not.

It was hard to realize he was no longer the impish jester who had both served and protected King Shrewd for all those years. His body had not changed, save in colouring. His graceful, long-fingered hands dangled off the arms of the chair. His hair, once as pale and airy as dandelion fluff, was now bound back from his face and confined to a golden queue. He closed his eyes and leaned his head back against the chair. Firelight bronzed his aristocratic profile. His present grand clothes might recall his old winter motley of black and white, but I wagered he would never again wear bells and ribbons and carry a rat-headed sceptre. His lively wit and sharp tongue no longer influenced the course of political events. His life was his own now. I tried to imagine him as a wealthy man, able to travel and live as he pleased. A sudden thought jolted me from my complacency.

‘Fool?’ I called aloud in the darkened rooms.

‘What?’ He did not open his eyes but his ready reply showed he had not yet slipped towards sleep.

‘You are not the Fool any more. What do they call you these days?’

A slow smile curved his lips in profile. ‘What do who call me when?’

He spoke in the baiting tone of the jester he had been. If I tried to sort out that question, he would tumble me in verbal acrobatics until I gave up hoping for an answer. I refused to be drawn into his game. I rephrased my question. ‘I should not call you Fool any more. What do you want me to call you?’

‘Ah, what do I want you to call me now? I see. An entirely different question.’ Mockery made music in his voice.

I drew a breath and made my question as plain as possible. ‘What is your name, your real name?’

‘Ah.’ His manner was suddenly grave. He took a slow breath. ‘My name. As in what my mother called me at my birth?’

‘Yes.’ And then I held my breath. He spoke seldom of his childhood. I suddenly realized the immensity of what I had asked him. It was the old naming magic: if I know how you are truly named, I have power over you. If I tell you my name, I grant you that power. Like all direct questions I had ever asked the Fool, I both dreaded and longed for the answer.

‘And if I tell you, you would call me by that name?’ His inflection told me to weigh my answer.

That gave me pause. His name was his, and not for me to bandy about. But, ‘In private, only. And only if you wished me to,’ I offered solemnly. I considered the words as binding as a vow.

‘Ah.’ He turned to face me. His face lit with delight. ‘Oh, but I would,’ he assured me.

‘Then?’ I asked again. I was suddenly uneasy, certain that somehow he had bested me yet again.

‘The name my mother gave me, I give now to you, to call me by in private.’ He took a breath and turned back to the fire. He closed his eyes again but his grin grew even wider. ‘Beloved. She called me only “Beloved”.’

‘Fool!’ I protested.

He laughed, a deep rich chuckle of pure enjoyment, completely pleased with himself. ‘She did,’ he insisted.

‘Fool, I’m serious.’ The room had begun to revolve slowly around me. If I did not go to sleep soon, I would be sick.

‘And you think I am not?’ He gave a theatrical sigh. ‘Well, if you cannot call me Beloved, then I suppose you should continue to call me Fool. For I am ever the Fool to your Fitz.’

‘Tom Badgerlock.’

‘What?’

‘I am Tom Badgerlock now. It is how I am known.’

He was silent for a time. Then, ‘Not by me,’ he replied decisively. ‘If you insist we must both take different names now, then I shall call you Beloved. And whenever I call you that, you may call me Fool.’ He opened his eyes and rolled his head to look at me. He simpered a lovesick smile, then heaved an exaggerated sigh. ‘Good night, Beloved. We have been apart far too long.’

I capitulated. Conversation was hopeless when he got into these moods. ‘Goodnight, Fool.’ I rolled over in my bed and closed my eyes. If he made any response, I was asleep before he uttered it.