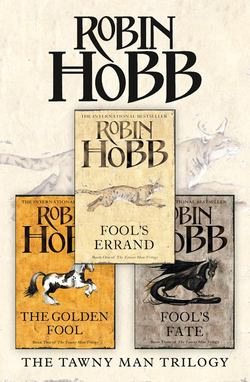

Читать книгу The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy: Fool’s Errand, The Golden Fool, Fool’s Fate - Робин Хобб - Страница 20

ELEVEN Chade’s Tower

ОглавлениеBetween the Six Duchies and the Out Islands as much blood has been shared as has been shed. Despite the enmity of the Red Ship War, and the years of sporadic raiding that preceded it, almost every family in the Coastal Duchies will acknowledge having ‘a cousin in the Out Islands’. All acknowledge that the folk of the Coastal Duchies are of those mingled bloodlines. It is well documented that the first rulers of the Farseer line were likely raiders from the Out Islands who came to raid and settled instead.

Just as the history of the Six Duchies has been shaped by geography, so too has the chronicle of the Out Islands. Theirs is a harsher land than ours. Ice rules their mountainous islands year round. Deep fjords slash their islands and rough water divides them. We consider their islands immense, yet the domination of glacier grants men only the edges of those islands as dwelling places. What arable land they have along the coasts of their islands is stingy and thin in its yield. Thus no large cities can be supported there, and few towns. Barriers and isolation are the hallmark of that land, and so the folk dwell in fiercely independent villages and town-states. In times past, they were raiders by necessity as well as by inclination, and robbed one another as often as they ventured across the seas to harry the Six Duchies coastline. It is true that during the Red Ship War, Kebal Rawbread was able to force a brief alliance among the island folk, and from that alliance, he hammered together a powerful raiding fleet. Only the devastation of the Six Duchies dragons was sufficient to shatter his merciless hold over his own people.

Having once seen the strength of such an alliance, the individual headmen of the Out Island villages realized that such power could be used for more than War. In the years of recovery that followed the end of the Red Ship War, the Hetgurd was formed. This alliance of Out Island headmen was an uneasy one. At first, they sought only to replace inter-island raiding with trading treaties between individual headmen. Arkon Bloodblade was the first headman to point out to the others that the Hetgurd could use its unified strength to normalize trade relations with the Six Duchies.

Brawnkenner’s The Out Island Chronicles

As always, Chade had planned well. His silent messenger seemed very familiar with his ways. Before noon the next day, we had changed our exhausted horses for two others at a decrepit farmhouse. We travelled across brown hillsides seared by summer, and left those two horses at a fisherman’s hut. A small boat was waiting and the surly crew took us swiftly up the coast. We put in at a landing at a tiny trading port, where two more horses awaited us at a run-down inn. I stayed as silent as my guide, and no one questioned me about anything. If coin was exchanged, I never saw it. It is always best not to see what is meant to be concealed. The horses carried us to yet another waiting boat, this one with a scaly deck that smelled much of fish. It struck me that we were approaching Buckkeep not by the swiftest possible path, but by the least likely one. If anyone watched the roads into Buckkeep for us, they were doomed to disappointment.

Buckkeep Castle is built on an inhospitable strip of coast. It stands, tall and black, on top of the cliffs, but it commands a fine view of the Buck River mouth. Whoever controls that castle controls trade on the Buck River. For that reason was it built there. The vagaries of history have made it the ruling seat of the Farseer family. Buckkeep Town clings to the cliffs below the castle like lichens to rock. Half of it is built out on docks and piers. As a boy, I had thought the town had grown as large as it could, given its geography, but on the afternoon that we sailed into it, I saw that I had been wrong. Human ingenuity had prevailed over nature’s harshness. Suspended pathways now vined across the face of the cliffs, and tiny houses and shops found purchase to cling there. The houses reminded me of mud-swallows’ nests, and I wondered what pounding they took during the winter storms. Pilings had been driven into the black sand and rock of the beaches where I had once run and played with Molly and the other children. Warehouses and inns squatted on these perches, and at high tide, one could tie up right at their doorsteps. This our fishing boat did, and I followed my mute guide ‘ashore’ onto a wooden walkway.

As the small boat cast off and left us there, I gawked about us, a country farmer come to town. The increase in structures and the lively boat commerce indicated that Buckkeep prospered, yet I could take no joy in it. Here was the final evidence of my childhood erased. The place I had both dreaded and longed to return to was gone, swallowed by this thriving port. When I glanced about for my mute guide, he had vanished. I loitered where he had left me a bit longer, already suspecting he would not return. He had brought me back to Buckkeep Town. From here, I needed no guide. Chade never liked any of his contacts to know every link of the convoluted paths that led to him. I shouldered my small rucksack and headed towards home.

Perhaps, I thought as I wended my way through Buckkeep’s steep and narrow streets, Chade had even known that I would prefer to make this part of my journey alone. I did not hurry. I knew I could not contact Chade until after nightfall. As I explored the once-familiar streets and byways, I found nothing that was completely familiar. It seemed that every structure that could sprout a second storey had, and on some of the narrower streets the balconies almost met overhead, so that one walked in a perpetual twilight. I found inns I had frequented and stores where I had traded, and even glimpsed the faces of old acquaintances overlaid with fifteen years of experience. Yet no one exclaimed with surprise or delight to see me; as a stranger I was visible only to the boys hawking hot pies in the street. I bought one for a copper and ate it as I walked. The taste of the peppery gravy and the chunks of river fish in it were the taste of Buckkeep Town itself.

The chandlery that had once belonged to Molly’s father was now a tailor’s shop. I did not go inside. I went instead to the tavern we had once frequented. It was as dark, as smoky, and as crowded as I recalled. The heavy table in the corner still bore the marks of Kerry’s idle whittling. The boy who brought my beer was too young ever to have known me, but I knew who had fathered him by the line of his brow and was glad the business had remained in the same family. One beer became two, and then three, and the fourth was gone before twilight began to creep through the streets of the town. No one had uttered a word to the dour-faced stranger drinking alone, but I listened all the same. But whatever desperate business had led Chade to call on me, it was not common knowledge. I heard only gossip of the Prince’s betrothal, complaints about Bingtown’s war with Chalced disrupting trade, and the local mutterings about the very strange weather. Out of a clear and peaceful night sky, lightning had struck an unused storage hut in the outer keep of the castle and blown the roof right off. I shook my head at that tale. I left an extra copper for the boy, and shouldered my pack once more.

The last time I had left Buckkeep it had been as a dead man in a coffin. I could scarcely re-enter the same way, and yet I feared to approach the main gate. Once I had been a familiar face in the guardroom. Changed I might be, but I would not take the chance of being recognized. Instead, I went to a place both Chade and I knew, a secret exit from the castle grounds that Nighteyes had discovered when he was just a cub. Through that small gap in Buckkeep’s defences, Queen Kettricken and the Fool had once fled Prince Regal’s plot. Tonight, I would return by that route.

But when I got there, I found that the fault in the walls that guarded Buckkeep had been repaired a long time ago. A heavy growth of thistles cloaked where it had been. A short distance from the thistles, sitting cross-legged on a large embroidered cushion, a golden-haired youth of obvious nobility played a penny whistle with consummate skill. As I approached, he ended his tune with a final scattering of notes and set his instrument aside.

‘Fool,’ I greeted him fondly and with no great surprise.

He cocked his head and made a mouth at me. ‘Beloved,’ he drawled in response. Then he grinned, sprang to his feet, and slipped his whistle inside his ribboned shirt. He indicated his cushion. ‘I’m glad I brought that. I had a feeling you might linger a time in Buckkeep Town, but I didn’t expect to wait this long.’

‘It’s changed,’ I said lamely.

‘Haven’t we all?’ he replied, and for a moment there was an echo of pathos in his voice. But in an instant it was gone. He tidied his gleaming hair fussily and picked a leaf from his stocking. He pointed at his cushion again. ‘Pick that up and follow me. Hurry along. We are expected.’ His air of petulant command mimed perfectly that of a foppish dandy of the noble class. He plucked a handkerchief from his sleeve and patted at his upper lip, erasing imaginary perspiration.

I had to smile. He assumed the role so deftly and effortlessly. ‘How are we going in?’

‘By the front gate, of course. Have no fear. I’ve put word about that Lord Golden is very dissatisfied with the quality of servants he has found in Buckkeep Town. None have suited me, and so today I went to meet a ship bringing to me a fine fellow, if a bit rustic, recommended to me by my second cousin’s first valet. By name, one Tom Badgerlock.’

He proceeded ahead of me. I picked up his cushion and followed. ‘So. I’m to be your servant?’ I asked in wry amusement.

‘Of course. It’s the perfect guise. You’ll be virtually invisible to all the nobility of Buckkeep. Only the other servants will speak to you, and as I intend that you will be a down-trodden, overworked, poorly-dressed lackey of a supercilious, overbearing and insufferable young lord, you will have little time to socialize at all.’ He halted suddenly and looked back. One slender, long-fingered hand clasped his chin as he looked down his nose at me. His fair brows knit and his amber eyes narrowed as he snapped, ‘And do not dare to meet my eyes, sirrah! I will tolerate no impertinence. Stand up straight, keep your place, and speak no word without my leave. Are you clear on these instructions?’

‘Perfectly,’ I grinned at him.

He continued to glare at me. Then suddenly the glare was replaced by a look of exasperation. ‘FitzChivalry, the game is up if you cannot play this role and play it to the hilt. Not just when we stand in the Great Hall of Buckkeep, but every moment of every day when there is the remotest chance that we might be seen. I have been Lord Golden since I arrived, but I am still a newcomer to the Queen’s Court, and folk will stare. Chade and Queen Kettricken have done all they could to help me in this ruse, Chade because he perceived how useful I might be, and the Queen because she feels I truly deserve to be treated as a lord.’

‘And no one recognized you?’ I broke in incredulously.

He cocked his head. ‘What would they recognize, Fitz? My dead white skin and colourless eyes? My jester’s motley and painted face? My capers and cavorting and daring witticisms?’

‘I knew you the moment I saw you,’ I reminded him.

He smiled warmly. ‘Just as I knew you, and would know you when first I met you a dozen lives hence. But few others do. Chade with his assassin’s eyes picked me out, and arranged a private audience at which I made myself known to the Queen. A few others have given me curious glances from time to time, but no one would dare to accost Lord Golden and ask him if fifteen years ago he had been King Shrewd’s jester at this self-same court. My age appears wrong to them, as does my colouring, as does my demeanour, as does my wealth.’

‘How can they be so blind?’

He shook his head and smiled at my ignorance. ‘Fitz, Fitz. They never even saw me in the first place. They saw only a jester and a freak. I deliberately took no name when first I arrived here. To most of the lords and ladies of Buckkeep, I was just the Fool. They heard my jokes and saw my capers, but they never really saw me.’ He gave a small sigh. Then he gave me a considering look. ‘You made it a name. The Fool. And you saw me. You met my eyes when others looked aside, disconcerted.’ I saw the tip of his tongue for a second. ‘Did you never guess how you frightened me? That all my ruses were useless against the eyes of a small boy?’

‘You were just a child yourself,’ I pointed out uneasily.

He hesitated. I noticed he did not agree or disagree with me when he went on. ‘Become my faithful servant, Fitz. Be Tom Badgerlock, every second of every day that you are at Buckkeep. It is the only way you can protect both of us. And the only guise in which you can aid Chade.’

‘What, exactly, does Chade need of me?’

‘That would be better heard from his lips than mine. Come. It grows dark. Buckkeep Town has grown and changed, as has Buckkeep itself. If we try to enter after dark, we may well be turned away.’

It had grown later as we talked and the long summer day was fading around us. He led and I followed as he took me round about to the steep road that led to Buckkeep Castle’s main gate. He lingered in the trees to let a wine merchant round a bend before we ourselves stepped out on the road. Then Lord Golden led and his humble servant Tom Badgerlock trudged behind him, bearing his embroidered cushion.

At the gate he was admitted without question and I followed at his heels, unnoticed. The guard on the gate wore Buckkeep’s blue and their jerkins were embroidered with the Farseer leaping buck. Small things like that twisted my heart unexpectedly. I blinked and then coughed and rubbed my eyes. The Fool had the kindness not to look back at me.

Buckkeep had changed as much as the town that clung to the cliffs below it. Overall, the changes were ones I approved. We passed a new and larger stable. Paving stones had been laid where once muddy tracks had run. Although more folk thronged the castle than I recalled, it seemed cleaner and better maintained. I wondered if this was Kettricken’s Mountain discipline applied to the keep, or simply the result of peace in the land. All the years that I had lived in Buckkeep had been years of the Outislander raids and eventually outright war. Relative peace had brought a resumption of trade, and not just with the countries to the south of the Six Duchies. Our history of trading with the Out Islands was as long as our history of fighting with them. I had seen the Outislander ships, both oared and sailed, in Buckkeep’s harbour when I arrived.

We entered through the Great Hall, Lord Golden striding imperiously along while I hastened, eyes down, at his heels. Two ladies detained him briefly with greetings. I think it was hardest then for me to keep my guise of serving-man in place. Where once the Fool had inspired unease or outright distaste, Lord Golden was greeted with fluttering fans and eyelashes. He charmed them both with a score of elegantly-woven compliments on their dresses, their hair, and the scents they wore. They parted with him reluctantly, and he assured them he was as loath to leave, but he had a servant to be shown his duties, and certainly they knew the drudgery of that. One simply could not get good servants any more, and although this one came with a high recommendation, he had already proven to be a bit slow-witted and woefully countrified. Well, one had to make do with what one could get these days, and he hoped to enjoy their company on the morrow. He planned to stroll through the thyme gardens after breakfast, if they cared to join him?

They would, of course, with great delight, and after several more rounds of exchanged pleasantries, we were allowed to go our way. Lord Golden had been given apartments on the west side of the keep. In King Shrewd’s day, these had been considered the less desirable rooms, for they faced the hills behind the keep and the sunset, rather than the water and the sunrise. In those days, they had been furnished more simply, and were considered suitable for lesser nobility.

Either the status of the rooms had improved, or the Fool had been very lavish with his own money. I opened a heavy oak door for him at his gesture, and then followed him into chambers where both taste and quality had been indulged in equal measure. Deep greens and rich browns predominated in the thick rugs underfoot and the opulently cushioned chairs. Through a door I glimpsed an immense bed, fat with pillows and featherbed, and so heavily draped that even in Buck’s coldest winter, no draught would find the occupant. For the summer weather, the heavy curtains had been roped back with tasselled cords, and a fall of lace sufficed to keep all flying insects at bay. Carved chests and wardrobes stood casually ajar, the volume of garments within threatening to cascade out into the room. There was an air of rich and pleasant disorder, completely unlike the Fool’s ascetic tower room that I recalled of old.

Lord Golden flung himself into a chair as I closed the door quietly behind us. A last slice of sunlight from the westering sun came in the tall window and fell across him as if by accident. He steepled his graceful hands before him and lolled his head back against the cushions, and suddenly I perceived the deliberate artifice of the chair’s position and his pose. This entire rich room was a setting for his golden beauty. Every colour chosen, every placement of furniture was done to achieve this end. In this place and time, he glowed in the honey light of the sunset. I lifted my eyes to consider the arrangement of the candles, the angles of the chairs.

‘You take your place like a figure stepping into a carefully-composed portrait,’ I observed quietly.

He smiled, his obvious pleasure in the compliment a confirmation of my words. Then he came to his feet as effortlessly as a cat. His arm and hand twined through a motion to point at each door off the room. ‘My bedchamber. The privy room. My private room.’ This door was closed, as was the last one. ‘And your chamber, Tom Badgerlock.’

I did not ask him about his private room. I knew his need for solitude of old. I crossed the room and tugged open the door to my quarters. I peered inside the small, dark room. It had no window. As my eye adjusted, I could make out a narrow cot in the corner, a washstand and a small chest. There was a single candle in a holder on the washstand. That was all. I turned back to the Fool with a quizzical look.

‘Lord Golden,’ he said with a wry smile, ‘is a shallow, venal fellow. He is witty and quick-tongued, and very charming to his fellows, and completely unaware of those of lesser stations. So. Your chamber reflects that.’

‘No window? No fireplace?’

‘No different from most of the servants’ chambers on this floor. It has, however, one singularly remarkable advantage that most of the others lack.’

I glanced back into the room. ‘Whatever it is, I don’t see it.’

‘And that is exactly what is intended. Come.’

Taking my arm, he accompanied me into the dark little room. He shut the door firmly behind us. We were instantly plunged into complete darkness. Speaking quietly next to me, he observed, ‘Always remember that the door must be shut for this to work. Over here. Give me your hand.’

I complied, and he guided my hand over the rough stone of the outer wall adjacent to the door. ‘Why must we do this in the dark?’ I demanded.

‘It was faster than kindling candles. Besides, what I am showing you cannot be seen, only felt. There. Feel that?’

‘I think so.’ It was a very slight unevenness in the stone.

‘Measure it off with your hand, or whatever you want to do to learn where it is.’

I obliged him, discovering that it was about six of my handspans from the corner of the room, and at the height of my chin. ‘Now what?’

‘Push. Gently. It does not take much.’

I obeyed and felt the stone shift very slightly beneath my hand. A small click sounded, but not from the wall before me. Instead, it came from behind me.

‘This way,’ the Fool told me, and in the darkness led me to the opposite wall of the small chamber. Again, he set my hand to the wall and told me to push. The darkness gave way on oiled hinges, the seeming stone no more than a façade that swung away at my touch. ‘Very quiet,’ the Fool observed approvingly. ‘He must have greased it.’

I blinked as my eyes adjusted to a subtle light leaking down from high above. In a moment I could see a very narrow staircase leading up. It paralleled the wall of the room. A corridor, equally narrow, snaked away into darkness, following the wall. ‘I believe you are expected,’ the Fool told me in his aristocratic sneer. ‘As is Lord Golden, but in far different company. I will excuse you from your duties as my valet, at least for tonight. You are dismissed, Tom Badgerlock.’

‘Thank you, master,’ I replied snidely. I craned my neck to peer up the stairs. They were stone, obviously built into the wall when the castle was first constructed. The grey quality of the light that seeped down suggested daylight rather than lamplight.

The Fool’s hand settled briefly on my shoulder, delaying me. In a far different voice he said, ‘I’ll leave a candle burning in the room for you.’ The hand squeezed affectionately. ‘And welcome home, FitzChivalry Farseer.’

I turned to look back at him. ‘Thank you, Fool.’ We nodded to one another, an oddly formal farewell, and I began to climb the stair. On the third stair, I heard a snick behind me, and looked back. The door had closed.

I climbed for quite a distance. Then the staircase turned, and I perceived the source of the light. Narrow openings, not even as wide as arrowslits, permitted the setting sun to finger in. The light was growing dimmer, and I suddenly perceived that when the sun set, I would be plunged into absolute darkness. I came to a junction in the corridor at that time. Truly, Chade’s rat-warren of tunnels, stairs and corridors within Buckkeep Castle were far more extensive than I had ever imagined. I closed my eyes for a moment and imagined the layout of the castle. After a brief hesitation, I chose a path and went on. As I travelled, from time to time I became aware of voices. Tiny peepholes gave me access to bedchambers and parlours as well as providing slivers of light in long dark stretches of corridor. A wooden stool, dusty with disuse, sat in one alcove. I sat down on it and peered through a slit into a private audience chamber that I recognized from my service with King Shrewd. Evidently the magnificent woodwork that framed the hearth furnished this spy post. Having taken my bearings from this, I hastened on.

At last, I saw a yellowish glow in the secret passageway far ahead of me. Hurrying towards it, I found a bend in the corridor, and a fat candle burning in a glass. Far down another stretch, I glimpsed a second candle. From that point on, the tiny lights led me on, until I climbed a very steep stair and suddenly found myself standing in a small stone room with a narrow door. The door swung open at my touch, and I found myself stepping out from behind the wine rack into Chade’s tower room.

I looked about the chamber with new eyes. It was uninhabited at the moment, but a small fire crackling on the hearth and a laden table told me I was, indeed, expected. The great bedstead was overladen with comforters, cushions and furs as it had always been, yet an elaborate spiderweb constructed amidst the dusty hangings spoke of disuse. Chade used this room still, but he no longer slept here.

I ventured down to the workroom end of the chamber, past the scroll-laden racks and the shelves of arcane equipment. Sometimes, when one goes back to the scene of one’s childhood, things seem smaller. What was mysterious and the sole province of adults suddenly seems commonplace and mundane when viewed with mature eyes.

Such was not the case with Chade’s workroom. The little pots carefully labelled in his decisive hand, the blackened kettles and stained pestles, the spilled herbs and the lingering odours still worked their spell on me. The Wit and the Skill were mine, but the strange chemistries that Chade practised here were a magic I had never mastered. Here I was still an apprentice, knowing only the basics of my master’s sophisticated lore.

My travels had taught me a bit. A shallow gleaming bowl, draped with a cloth, was a scrying basin. I’d seen them used by fortune-tellers in Chalcedean towns. I thought of the night that Chade had wakened me from a drunken stupor to tell me that Neat Bay was under attack from Red Ship Raiders. There had been no time, that night, to demand how he knew. I had always assumed it had been a messenger bird. Now I wondered.

The work hearth was cold, but tidier than I recalled. I wondered who his new apprentice was, and if I would meet the lad. Then my musings were cut short by the sound of a door closing softly. I turned to see Chade Fallstar standing near a scroll rack. For the first time, I realized that there were no obvious doors in the chamber. Even here, all was still deception. He greeted me with a warm if weary smile. ‘And here you are at last. When I saw Lord Golden enter the Great Hall smiling, I knew you would be awaiting me. Oh, Fitz, you have no idea how relieved I am to see you.’

I grinned at him. ‘In all our years together, I can’t recall a more ominous greeting from you.’

‘It’s an ominous time, my boy. Come, sit down, eat. We’ve always reasoned best over food. I’ve so much to tell you, and you may as well hear it with a full belly.’

‘Your messenger did not tell me much,’ I admitted, taking a place at the small lavishly-spread table. There were cheeses, pastries, cold meats, fruit that was fragrantly ripe, and spicy breads. There was both wine and brandy, but Chade began with tea from an earthenware pot warm at the edge of the fire. When I reached for the pot, a gesture of his hand warded me off.

‘I’ll put on more water,’ he offered, and hung a kettle to boil. I watched the set of his mouth as he sipped the dark brew in his cup. He did not seem to relish it, yet he sank back in his chair with a sigh. I kept my thoughts to myself.

As I began to heap my plate, Chade noted, ‘My messenger told you as much as he knew, which was nothing. One of my greatest tasks has been to keep this private. Ah, where do I begin? It is hard to decide, for I don’t know what precipitated this crisis.’

I swallowed a mouthful of bread and ham. ‘Tell me the heart of it, and we can work backwards from there.’

His green eyes were troubled. ‘Very well.’ He took breath, then hesitated. He poured us both brandy. As he set mine before me he said, ‘Prince Dutiful is missing. We think he might have run on his own. If he did, he likely had help. It is possible that he was taken against his will, but neither the Queen nor I think that likely. There.’ He sat back in his chair and watched for my reaction.

It took me a moment to marshal my thoughts. ‘How could it happen? Who do you suspect? How long has he been gone?’

He held up a hand to halt my flow of questions. ‘Six days and seven nights, counting tonight. I doubt he will reappear before morning, though nothing would please me better. How did it happen? Well, I do not criticize my queen, but her Mountain ways are often difficult for me to accept. The Prince has come and gone as he pleased from both castle and keep since he was thirteen. She seemed to think it best that he get to know his people on a common footing. There have been times when I thought that was wise, for it has made the folk fond of him. I myself have felt that it was time he had a guard of his own to accompany him, or at the least a tutor of the well-muscled sort. But Kettricken, as you may recall, can be as unbending as stone. In that, she had her way. He came and went as he wished, and the guards had their orders to let him do so.’

The water was boiling. Chade still kept teas where he always had, and he made no comment as I rose to make my tea. He seemed to be gathering his thoughts, and I let him, for my own thoughts were milling in every direction like a panicky flock of sheep. ‘He could already be dead,’ I heard myself say aloud, and then could have bitten my tongue out at the stricken look on Chade’s face.

‘He could,’ the old man admitted. ‘He is a hearty, healthy boy, unlikely to turn away from a challenge. This absence need not be a plot; an ordinary accident could be at the base of it. I thought of that. I’ve a discreet man or two at my beck, and they’ve searched the base of the sea cliffs, and the more dangerous ravines where he likes to hunt. Still, I think that if he were injured, his little hunting cat might still have come back to the castle. Though it is hard to say with cats. A dog would, I think, but a cat might just revert to being wild. In any case, unpleasant as the idea is, I have thought to look for a body. None has been discovered.’

A hunting cat. I ignored my jabbing thought to ask, ‘You said run away, or possibly taken. What would make you think either one likely?’

‘The first, because he’s a boy trying to learn to be a man in a Court that makes neither easy for him. The second, because he’s a prince, newly betrothed to a foreign princess, and rumoured to be possessed of the Wit. That gives several factions any number of reasons to either control him or destroy him.’

He gave me several silent minutes to digest that. Several days would not have been enough. I must have looked as sick as I felt, for Chade finally said, softly, ‘We think that even if he has been taken, he is most valuable to his kidnappers alive.’

I found a breath and spoke through a dry mouth. ‘Has anyone claimed to have him? Demanded ransom?’

‘No.’

I cursed myself for not staying abreast of politics in the Six Duchies. But had not I sworn never to become involved in them again? It suddenly seemed a child’s foolish resolve never to get caught in the rain again. I spoke quietly, for I felt ashamed. ‘You are going to have to educate me, Chade, and swiftly. What factions? How does it benefit their interests to have control of the Prince? What foreign princess? And –’ and this last question near choked me, ‘– Why would anyone think Prince Dutiful was Witted?’

‘Because you were,’ Chade said shortly. He reached again for his teapot and replenished his cup. It poured even blacker this time, and I caught a whiff of a treacly yet bitter-edged aroma. He gulped down a mouthful, and swiftly followed it with a toss of brandy. He swallowed. His green eyes met mine and he waited. I said nothing. Some secrets still belonged to me alone. At least, I hoped they did.

‘You were Witted,’ he resumed. ‘Some say it must have come from your mother, whoever she was, and Eda forgive me, I’ve encouraged that thinking. But others point back a time, to the Piebald Prince and several other oddlings in the Farseer line, to say, “No, the taint is there, down in the roots, and Prince Dutiful is a shoot from that line.”’

‘But the Piebald Prince died without issue; Dutiful is not of his line. What made folk think that the Prince might be Witted?’

Chade narrowed his eyes at me. ‘Do you play Cat-And-Mouse with me, boy?’ He set his hands on the edge of the table. Veins and tendons stood up ropily on their backs as he leaned towards me to demand, ‘Do you think I’m losing my faculties, Fitz? Because I can assure you, I’m not. I may be getting old, boy, but I’m as acute as ever. I promise you that!’

Until that moment, I had not doubted it. This outburst was so uncharacteristic of Chade that I found myself leaning back in my chair and regarding him with apprehension. He must have interpreted the look in my eyes, for he sat back in his chair and dropped his hands into his lap. When he spoke again, it was my mentor of old that I heard. ‘Starling told you of the minstrel at Springfest. You know of the unrest in the land among the Witted, yes, and you know of those who call themselves the Piebalds. There is an unkinder name for them. The Cult of the Bastard.’ He gave me a baleful look, but gave me no time to absorb that information. He waved a hand, dismissing my shock. ‘Whatever they call themselves, they have recently taken up a new weapon. They expose families tainted by the Wit. I do not know if they seek to prove how widespread the Wit is, or if their aim is the destruction of their fellows who will not ally with them. Posts appear in public places. “Gere the Tanner’s son is Witted; his beast is a yellow hound.” “Lady Winsome is Witted; her beast is her merlin.” Each post is signed with their emblem, a piebald horse. Who is Witted and who is not has become court gossip these days. Some deny the rumours; others flee, to country estates if they are landed, to a distant village and a new name if they are not. If those posts are true, there are far more who possess the Beast Magic than even you might suppose. Or,’ and he cocked his head at me, ‘do you know far more of all this than I do?’

‘No,’ I replied mildly. ‘I do not.’ I cleared my throat. ‘Nor was I aware how completely Starling reported to you.’

He steepled his hands under his chin. ‘I’ve offended you.’

‘No,’ I lied. ‘It’s not that, it’s that –’

‘Damn me. I’ve become a testy old man despite all I’ve done to avoid it! And I offend you and you lie to me about it and when only you can aid me, I drive you away from me. My judgement fails me just when I need it most.’

His eyes suddenly met mine and horror stood in his gaze. Before my eyes, the old man dwindled. His voice became an uncertain whisper. ‘Fitz, I am terrified for the boy. Terrified. The accusation was not posted publicly. It was sent in a sealed note. It was not signed at all, not even with the Piebalds’ sigil. “Do what is right,” it said, “and no one else ever need know. Ignore this warning, and we will take action of our own.” But they didn’t say what they wanted of us, not specifically, so what could we do? We didn’t ignore it; we simply waited to hear more. And then he is gone. The Queen fears … the Queen fears too many things to list. She fears most that they will kill him. But what I fear is worse than that. Not just that they will kill him, but that they will reduce him to … to what you were when Burrich and I first pulled you from that false grave. A beast in a man’s body.’

He rose suddenly and walked away from the table. I do not know if he felt shamed that his love for the boy could reduce him to such terror, or if he sought to spare me the recollection of what I had been. He need not have bothered. I had become adept at refusing those memories. He stared unseeing at a tapestry for a time, then cleared his throat. When he went on, it was the Queen’s advisor who spoke. ‘The Farseer throne would not stand before that, FitzChivalry. We have needed a king for too long. If the boy were proven Witted, even that I think I could manage to set in a different light. But if he were shown to his dukes as a beast, all would come undone, and the Six Duchies will never become the Seven Duchies, but will instead be reduced to squabbling city-states and lands between that know no rule. Kettricken and I have come such a long and weary road, my boy, in the years that you have been gone. Neither she nor I can really muster the unquestionable authority that a true Farseer-born king could wield. Through the years, we have sailed a shifting sea of alliances with first these dukes, then those ones, always netting a majority that allowed us to survive another season. We are so close now, so close. In two more years, he will be prince no more, but take the title of King-in-Waiting. One year of that, and I think I could persuade the dukes to recognize him as a full king. Then, I think, we might feel secure for a time. When King Eyod of the Mountains dies, Dutiful inherits his mantle as well. We will have the Mountains at our back, and if this marriage alliance Kettricken has negotiated with the Out Islands hetgurd prospers, we will have friendship in the seas to the North.’

‘Hetgurd?’

‘An alliance of nobles. They have no king there, no high ruler. Kebal Rawbread was an anomaly for them. But this hetgurd has a number of powerful men in it, and one of them, Arkon Bloodblade, has a daughter. Messages have gone back and forth. His daughter and Dutiful seem to be suitable for one another. The Hetgurd has sent a delegation to formally recognize their betrothal. It will be here soon. If Prince Dutiful meets their expectations, the affiancing will be recognized at a ceremony at the next new moon.’ He turned back to me, shaking his head. ‘I fear it is too soon for such an alliance. Bearns does not like it, nor Rippon. They would probably profit from the renewed trade, but the wounds are still too fresh. Better, I would think, to wait another five years, let the trade swell slowly between the countries, let Dutiful take up the reins of the Six Duchies, and then propose an alliance. Not with my prince, but with a lesser offering. A daughter of one of the dukes, perhaps a younger son … but that is only my advice. I am not the Queen, and the Queen has made her will known. She will have peace in her lifetime, she proclaims. I think she attempts too much: to meld the Mountain Kingdom into the Six Duchies as a seventh, and to put an Outislander woman on our throne as queen. It is too much, too soon …’

It was almost as if he had forgotten I was there. He thought aloud before me, with a carelessness that he had never displayed in the years when Shrewd was on the throne. In those years, he would never have spoken a word of doubt on any of the king’s decisions. I wonder if he regarded our foreign-born queen as more fallible, or if he deemed me now mature enough to hear his misgivings. He took his chair across from me and again our eyes met.

In that moment, cold walked up my spine as I realized what I confronted. Chade was not the man he had been. He had aged, and despite his denials, the keen mind fought to shine past the fluttering curtains of his years. Only the structure of his spy-web, built so painstakingly through the years, sustained his power now. Whatever drugs he brewed in his teapot were not quite enough to firm the façade. To realize that was like missing a step on a dark steep stair. I suddenly grasped just how far and how swiftly we all could fall.

I reached across the table to set my hand upon his. I swear, I strove to will strength into him. I gripped his eyes with mine and sought to give him confidence. ‘Begin the night before he disappeared,’ I suggested quietly. ‘And tell me all that you know.’

‘After all these years, I should report to you, and let you draw the conclusions?’ I thought I had affronted him, but then his smile dawned. ‘Ah, Fitz, thank you. Thank you, boy. After all these years, it is so good to have you back at my side. So good to have someone I can trust. The night before Prince Dutiful vanished. Well. Let me see, then.’

For a time, those green eyes looked far afield. I feared for a moment that I had sent his mind wandering, but then he suddenly looked back at me, and his glance was keen. ‘I’ll go back a bit farther than that. We had quarrelled that morning, the Prince and I. Well, not quarrelled exactly. Dutiful is too mannered to quarrel with an elder. But I had lectured him, and he had sulked, much as you used to. I declare, sometimes it is a wonder to me how much that boy can put me in mind of you.’ He huffed out a brief sigh.

‘Anyway. We had had a little confrontation. He came to me for his morning Skill-lesson, but he could not keep his mind on it. There were circles under his eyes, and I knew he had been out late again with that hunting cat of his. And I warned him, sharply, that if he could not regulate himself so as to arrive refreshed and ready for lessons, it could be done for him. The cat could be put out in the stables with the other coursing beasts to assure that my prince would get a good sleep every night.

‘That, of course, ill suited him. He and that cat have been inseparable ever since the beast was given to him. But he did not speak of the cat or his late night excursions, possibly because he thinks I am less well informed of them than I truly am. Instead he attacked the lessons, and his tutor, as being at fault. He told me that he had no head for the Skill and never would no matter how much sleep he got. I told him not to be ridiculous, that he was a Farseer and the Skill was in his blood. He had the nerve to tell me that I was the one being ridiculous, for I had but to look in the mirror to see a Farseer who had no Skill.’

Chade cleared his throat and sat back in his chair. It took me a moment to realize that he was amused, not annoyed. ‘He can be an insolent pup,’ he growled, but in his complaint I heard a fondness, and a pride in the boy’s spirit. It amused me in a different way. A much milder remark from me at that age would have earned me a good rap on the head. The old man had mellowed. I hoped his tolerance for the boy’s insolence would not ruin him. Princes, I thought, needed more discipline than other boys, not less.

I offered a distraction of my own. ‘Then you’ve begun teaching him the Skill.’ I put no judgement in my voice.

‘I’ve begun trying,’ Chade growled, and there was concession in his. ‘I feel like a mole telling an owl about the sun. I’ve read the scrolls, Fitz, and I’ve attempted the meditations and the exercises they suggest. And sometimes I almost feel … something. But I don’t know if it’s what I’m meant to feel or only an old man’s wistful imagining.’

‘I told you,’ I said, and I kept my voice gentle. ‘It can’t be learned, nor taught, from a scroll. The meditation can ready you for it, but then someone has to show it to you.’

‘That’s why I sent for you,’ he replied, too quickly. ‘Because you are not only the only one who can properly teach the Skill to the Prince. You are also the only one who can use it to find him.’

I sighed. ‘Chade, the Skill doesn’t work that way. It –’

‘Say rather that you were never taught to use the Skill that way. It’s in the scrolls, Fitz. It says that two who have been joined by the Skill can find one another with it, if they need to. All my other efforts to find the Prince have failed. Dogs put on his scent ran well for half the morning, and then raced in circles, whimpering in confusion. My best spies have nothing to tell me, bribes have bought me nothing. The Skill is all that is left, I tell you.’

I thrust aside my piqued curiosity. I did not want to see the scrolls. ‘Even if the scrolls claim it can be done, you say it happens between two who have been joined by the Skill. The Prince and I have no such –’

‘I think you do.’

There is a certain tone of voice Chade has that stops one from speaking. It warns that he knows far more than you think he does, and cautions you against telling him lies. It was extremely effective when I was a small boy. It was a bit of a shock to find it was no less effective now that I was a man. I slowly drew breath into my lungs but before I could ask, he answered me.

‘Certain dreams the Prince has recounted to me first woke my suspicions. They started with occasional dreams when he was very small. He dreamed of a wolf bringing down a doe, and a man rushing up to cut her throat. In the dream, he was the man, and yet he could also see the man. That first dream excited him. For a day and a half, he spoke of little else. He told it as if it were something he had done himself.’ He paused. ‘Dutiful was only five at the time. The detail of his dream far exceeded his own experience.’

I still said nothing.

‘It was years before he had another such dream. Or, perhaps I should say it was years before he spoke to me of one. He dreamed of a man fording a river. The water threatened to sweep him away, but at the last he managed to cross it. He was too wet and too cold to build a fire to warm himself, but he lay down in the shelter of a fallen tree. A wolf came to lie beside him and warm him. And again, the Prince told me this dream as something that he himself had done. “I love it,” he told me. “It is almost as if there is another life that belongs to me, one that is far away and free of being a prince. A life that belongs to me alone, where I have a friend who is as close as my own skin.” It was then that I suspected he had had other such Skill-dreams, but had not shared them with me.’

He waited, and this time I had to break my silence.

I took a breath. ‘If I shared those moments of my life with the Prince, I was unaware of it. But, yes, those are true events.’ I halted, suddenly wondering what else he had shared. I recalled Verity’s complaint that I did not guard my thoughts well, and that my dreams and experiences sometimes intruded on his. I thought of my trysts with Starling and prayed I would not blush. It had been a very long time since I had bothered to set Skill-walls round myself. Obviously, I must do so again. Another thought came in the wake of that. Obviously, my Skill-talent had not degraded as much as I believed. A surge of exhilaration came with that thought. It was probably, I told myself viciously, much the same as what a drunk felt on discovering a forgotten bottle beneath the bed.

‘And you have shared moments of the Prince’s life?’ Chade pressed me.

‘Perhaps. I suspect so. I often have vivid dreams, and to dream of being a boy in Buckkeep is not so foreign from my own experience. But –’ I took a breath and forced myself on. ‘The important thing here is the cat, Chade. How long has he had it? Do you think he is Witted? Is he bonded to the cat?’

I felt like a liar, asking questions when I already knew the answers. My mind was rapidly shuffling through my dreams of the last fifteen years, sorting out those that came with the peculiar clarity that lingered after waking. Some could have been episodes from the Prince’s life. Others – I halted at the recollection of my fever dream of Burrich – Nettle, too? Dream sharing with Nettle? This new insight reordered my memory of the dream. I had not just witnessed those events from Nettle’s perspective. I had been Skill-sharing her life. It was possible that, as with Dutiful, the flow of Skill-sharing had gone both ways. What had seemed a cherished glimpse into her life, a tiny window on Molly and Burrich, was now revealed as her vulnerability before my carelessness. I winced away from the thought and resolved a stronger wall about my thoughts. How could I have been so incautious? How many of my secrets had I spilled before those most vulnerable to them?

‘How would I know if the boy was Witted?’ Chade replied testily. ‘I never knew you were, until you told me. Even then, I didn’t know what you were telling me at first.’

I was suddenly weary, too tired to lie. Who was I trying to protect with deceit? I knew too well that lies did not shield for long, that in the end they became the largest chinks in any man’s armour. ‘I suspect he is. And bonded to the cat. From dreams I’ve had.’

Before my eyes, the man aged. He shook his head wordlessly, and poured more brandy for both of us. I drank mine off while he drank his in long, considering sips. When he finally spoke, he said, ‘I hate irony. It is a manacle that ties our dreams to our fears. I had hoped you had a dream-bond with the boy, a tie that would let you use the Skill to find him. And indeed you do, but with it you reveal my greatest fear for Dutiful is real. The Wit. Oh, Fitz. I wish I could go back and make my fears foolish instead of real.’

‘Who gave him the cat?’

‘One of the nobles. It was a gift. He receives far too many gifts. All try to curry favour with him. Kettricken tries to turn aside those of the more valuable sort. She worries it will spoil the boy. But it was only a little hunting cat … yet it may be the gift that spoils him for his life.’

‘Who gave it to him?’ I pressed.

‘I will have to look back in my journals,’ Chade confessed. He gave me a dark look. ‘You can’t expect an old man to have a young man’s memory. I do the best I can, Fitz.’ His reproachful look spoke volumes. If I had returned to Buckkeep, resumed my tasks at his side, I would know these vital answers. The thought brought a new question to my mind.

‘Where is your new apprentice in all this?’

He met my gaze speculatively. After a moment he said, ‘Not ready for tasks such as these.’

I met his gaze squarely. ‘Is he, perhaps, recovering from, well, from a lightning strike from a clear sky? One that exploded an unused storage shed?’

He blinked, but kept control of his face. Even his voice remained steady as he ignored my thrust. ‘No, FitzChivalry, this task belongs to you. Only you have the unique abilities needed.’

‘What, exactly, do you want of me?’ The question was as good as surrender. I had already hastened to his side at his call. He knew I was still his. So did I.

‘Find the Prince. Return him to us, discreetly, and Eda save us, unharmed. And do it while my excuses for his absence are still believable. Get him home safely to us before the Outislander delegation arrives to formalize the betrothal to their princess.’

‘How soon is that?’

He shrugged helplessly. ‘It depends on the winds and the waves and the strength of their oarsmen. They have already departed the Out Islands. We had a bird to tell us so. The formality is scheduled for the new moon. If they arrive before that and the Prince is not here, I could, perhaps, fabricate something about his meditating alone before such a serious event in his life. But it would be a thin façade, one that would crumble if he did not appear for the ceremony.’

I reckoned it quickly in my head. ‘That’s more than a fortnight away. Plenty of time for a recalcitrant boy to change his mind and run home again.’

Chade looked at me sombrely. ‘Yet if the Prince has been taken, and we do not yet know by whom or why, let alone how we will recover him, then sixteen days seems but a pittance of time.’

I put my head in my hands for a moment. When I looked up, my old mentor was still regarding me hopefully. Trusting me to see a solution that eluded him. I wanted to flee; I wanted never to have known any of this. I took a steadying breath. Then I ordered his mind as he had once disciplined mine. ‘I need information,’ I announced. ‘Don’t assume I know anything about the situation, because it is likely I don’t. I need to know, first of all, who gave him the cat. And how does that person feel about the Wit, and the Prince’s betrothal? Expand the circle from there. Who rivals the gift-giver, who allies with him? Who at court most strongly persecutes those with the Wit, who most directly opposes the Prince’s betrothal, who supports it? Which nobles have most recently been accused of having the Wit in their families? Who could have helped Dutiful run, if run he did? If he was taken, who had the opportunity? Who knew his midnight habits?’ Each question I formulated seemed to beget another, yet in the face of that volley, Chade seemed to grow steadier. These were questions he could answer, and his ability to answer them strengthened his belief that together we might prevail. I paused for breath.

‘And I still need to report to you the events of those days. However, you seem to be forgetting that the Skill might save us hours of talk. Let me show you the scrolls, and see if they make more sense to you than they do to me.’

I looked around me, but he shook his head. ‘I do not bring the Prince here. This part of the castle remains a secret from him. I keep the Skill-scrolls in Verity’s old tower, and it is there that the boy has his lessons. I keep the tower room well secured, and a trusted guard is always before the door.’

‘Then how am I to have access to them?’

He cocked his head at me. ‘There is a way to them, from here to Verity’s tower. It’s a winding and narrow way, with many steps, but you’re a young man. You can manage them. Finish eating. Then I will show you the way.’