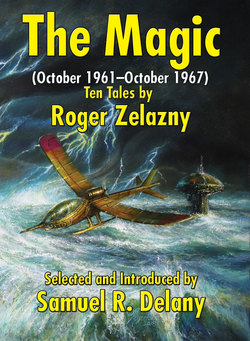

Читать книгу The Magic (October 1961–October 1967) - Roger Zelazny - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Rose for Ecclesiastes I

ОглавлениеI was busy translating one of my Madrigals Macabre into Martian on the morning I was found acceptable. The intercom had buzzed briefly, and I dropped my pencil and flipped on the toggle in a single motion.

“Mister G,” piped Morton’s youthful contralto, “the old man says I should ‘get hold of that damned conceited rhymer’ right away, and send him to his cabin. Since there’s only one damned conceited rhymer . . . ”

“Let not ambition mock thy useful toil.” I cut him off.

So, the Martians had finally made up their minds! I knocked an inch and a half of ash from a smoldering butt, and took my first drag since I had lit it. The entire month’s anticipation tried hard to crowd itself into the moment, but could not quite make it. I was frightened to walk those forty feet and hear Emory say the words I already knew he would say; and that feeling elbowed the other one into the background.

So I finished the stanza I was translating before I got up.

It took only a moment to reach Emory’s door. I knocked twice and opened it, just as he growled, “Come in.”

“You wanted to see me?” I sat down quickly to save him the trouble of offering me a seat.

“That was fast. What did you do, run?”

I regarded his paternal discontent:

Little fatty flecks beneath pale eyes, thinning hair, and an Irish nose; a voice a decibel louder than anyone else’s . . . .

Hamlet to Claudius: “I was working.”

“Hah!” he snorted. “Come off it. No one’s ever seen you do any of that stuff.”

I shrugged my shoulders and started to rise.

“If that’s what you called me down here—”

“Sit down!”

He stood up. He walked around his desk. He hovered above me and glared down. (A hard trick, even when I’m in a low chair.)

“You are undoubtably the most antagonistic bastard I’ve ever had to work with!” he bellowed, like a belly-stung buffalo. “Why the hell don’t you act like a human being sometime and surprise everybody? I’m willing to admit you’re smart, maybe even a genius, but—oh, hell!” He made a heaving gesture with both hands and walked back to his chair.

“Betty has finally talked them into letting you go in.” His voice was normal again. “They’ll receive you this afternoon. Draw one of the jeepsters after lunch, and get down there.”

“Okay,” I said.

“That’s all, then.”

I nodded, got to my feet. My hand was on the doorknob when he said:

“I don’t have to tell you how important this is. Don’t treat them the way you treat us.”

I closed the door behind me.

*

I don’t remember what I had for lunch. I was nervous, but I knew instinctively that I wouldn’t muff it. My Boston publishers expected a Martian Idyll, or at least a Saint-Exupéry job on space flight. The National Science Association wanted a complete report on the Rise and Fall of the Martian Empire.

They would both be pleased. I knew.

That’s the reason everyone is jealous—why they hate me. I always come through, and I can come through better than anyone else.

I shoveled in a final anthill of slop, and made my way to our car barn. I drew one jeepster and headed it toward Tirellian.

Flames of sand, lousy with iron oxide, set fire to the buggy. They swarmed over the open top and bit through my scarf; they set to work pitting my goggles.

The jeepster, swaying and panting like a little donkey I once rode through the Himalayas, kept kicking me in the seat of the pants. The Mountains of Tirellian shuffled their feet and moved toward me at a cockeyed angle.

Suddenly I was heading uphill, and I shifted gears to accommodate the engine’s braying. Not like Gobi, not like the Great Southwestern Desert, I mused. Just red, just dead . . . without even a cactus.

I reached the crest of the hill, but I had raised too much dust to see what was ahead. It didn’t matter, though; I have a head full of maps. I bore to the left and downhill, adjusting the throttle. A crosswind and solid ground beat down the fires. I felt like Ulysses in Malebolge—with a terza-rima speech in one hand and an eye out for Dante.

I rounded a rock pagoda and arrived.

Betty waved as I crunched to a halt, then jumped down.

“Hi,” I choked, unwinding my scarf and shaking out a pound and a half of grit. “Like, where do I go and who do I see?”

She permitted herself a brief Germanic giggle—more at my starting a sentence with “like” than at my discomfort—then she started talking. (She is a top linguist, so a word from the Village Idiom still tickles her!)

I appreciate her precise, furry talk; informational, and all that. I had enough in the way of social pleasantries before me to last at least the rest of my life. I looked at her chocolate-bar eyes and perfect teeth, at her sun-bleached hair, close-cropped to the head (I hate blondes!), and decided that she was in love with me.

“Mr. Gallinger, the Matriarch is waiting inside to be introduced. She has consented to open the Temple records for your study.” She paused here to pat her hair and squirm a little. Did my gaze make her nervous?

“They are religious documents, as well as their only history,” she continued, “sort of like the Mahabharata. She expects you to observe certain rituals in handling them, like repeating the sacred words when you turn pages—she will teach you the system.”

I nodded quickly, several times.

“Fine, let’s go in.”

“Uh—” She paused. “Do not forget their Eleven Forms of Politeness and Degree. They take matters of form quite seriously—and do not get into any discussions over the equality of the sexes—”

“I know all about their taboos,” I broke in. “Don’t worry. I’ve lived in the Orient, remember?”

She dropped her eyes and seized my hand. I almost jerked it away.

“It will look better if I enter leading you.”

I swallowed my comments, and followed her, like Samson in Gaza.

*

Inside, my last thought met with a strange correspondence. The Matriarch’s quarters were a rather abstract version of what I might imagine the tents of the tribes of Israel to have been like. Abstract, I say, because it was all frescoed brick, peaked like a huge tent, with animal-skin representations like gray-blue scars, that looked as if they had been laid on the walls with a palette knife.

The Matriarch, M’Cwyie, was short, white-haired, fifty-ish, and dressed like a queen. With her rainbow of voluminous skirts she looked like an inverted punch bowl set atop a cushion.

Accepting my obeisances, she regarded me as an owl might a rabbit. The lids of those black, black eyes jumped upwards as she discovered my perfect accent. —The tape recorder Betty had carried on her interviews had done its part, and I knew the language reports from the first two expeditions, verbatim. I’m all hell when it comes to picking up accents.

“You are the poet?”

“Yes,” I replied.

“Recite one of your poems, please.”

“I’m sorry, but nothing short of a thorough translating job would do justice to your language and my poetry, and I don’t know enough of your language yet.”

“Oh?”

“But I’ve been making such translations for my own amusement, as an exercise in grammar,” I continued. “I’d be honored to bring a few of them along one of the times that I come here.”

“Yes. Do so.”

Score one for me!

She turned to Betty.

“You may go now.”

Betty muttered the parting formalities, gave me a strange sideways look, and was gone. She apparently had expected to stay and “assist” me. She wanted a piece of the glory, like everyone else. But I was the Schliemann at this Troy, and there would be only one name on the Association report!

M’Cwyie rose, and I noticed that she gained very little height by standing. But then I’m six-six and look like a poplar in October; thin, bright red on top, and towering above everyone else.

“Our records are very, very old,” she began. “Betty says that your word for that age is ‘millennia.’”

I nodded appreciatively.

“I’m very eager to see them.”

“They are not here. We will have to go into the Temple—they may not be removed.”

I was suddenly wary.

“You have no objections to my copying them, do you?”

“No. I see that you respect them, or your desire would not be so great.”

“Excellent.”

She seemed amused. I asked her what was so funny.

“The High Tongue may not be so easy for a foreigner to learn.”

It came through fast.

No one on the first expedition had gotten this close. I had had no way of knowing that this was a double-language deal—a classical as well as a vulgar. I knew some of their Prakrit, now I had to learn all their Sanskrit.

“Ouch, and damn!”

“Pardon, please?”

“It’s non-translatable, M’Cwyie. But imagine yourself having to learn the High Tongue in a hurry, and you can guess at the sentiment.”

She seemed amused again, and told me to remove my shoes.

She guided me through an alcove . . .

. . . and into a burst of Byzantine brilliance!

*

No Earthman had ever been in this room before, or I would have heard about it. Carter, the first expedition’s linguist, with the help of one Mary Allen, M.D., had learned all the grammar and vocabulary that I knew while sitting cross-legged in the antechamber.

We had had no idea this existed. Greedily, I cast my eyes about. A highly sophisticated system of esthetics lay behind the decor. We would have to revise our entire estimation of Martian culture.

For one thing, the ceiling was vaulted and corbeled; for another, there were side-columns with reverse flutings; for another—oh hell! The place was big. Posh. You could never have guessed it from the shaggy outsides.

I bent forward to study the gilt filigree on a ceremonial table. M’Cwyie seemed a bit smug at my intentness, but I’d still have hated to play poker with her.

The table was loaded with books.

With my toe, I traced a mosaic on the floor.

“Is your entire city within this one building?”

“Yes, it goes far back into the mountain.”

“I see,” I said, seeing nothing.

I couldn’t ask her for a conducted tour, yet.

She moved to a small stool by the table.

“Shall we begin your friendship with the High Tongue?”

I was trying to photograph the hall with my eyes, knowing I would have to get a camera in here, somehow, sooner or later. I tore my gaze from a statuette and nodded, hard.

“Yes, introduce me.”

I sat down.

For the next three weeks alphabet-bugs chased each other behind my eyelids whenever I tried to sleep. The sky was an unclouded pool of turquoise that rippled calligraphies whenever I swept my eyes across it. I drank quarts of coffee while I worked and mixed cocktails of Benzedrine and champagne for my coffee breaks.

M’Cwyie tutored me two hours every morning, and occasionally for another two in the evening. I spent an additional fourteen hours a day on my own, once I had gotten up sufficient momentum to go ahead alone.

And at night the elevator of time dropped me to its bottom floors . . .

*

I was six again, learning my Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and Aramaic. I was ten, sneaking peeks at the Iliad. When Daddy wasn’t spreading hellfire brimstone, and brotherly love, he was teaching me to dig the Word, like in the original.

Lord! There are so many originals and so many words! When I was twelve I started pointing out the little differences between what he was preaching and what I was reading.

The fundamentalist vigor of his reply brooked no debate. It was worse than any beating. I kept my mouth shut after that and learned to appreciate Old Testament poetry.

—Lord, I am sorry! Daddy—Sir—I am sorry! —It couldn’t be! It couldn’t be . . . .

On the day the boy graduated from high school, with the French, German, Spanish, and Latin awards, Dad Gallinger had told his fourteen-year old, six-foot scarecrow of a son that he wanted him to enter the ministry. I remember how his son was evasive:

“Sir,” he had said, “I’d sort of like to study on my own for a year or so, and then take pre-theology courses at some liberal arts university. I feel I’m still sort of young to try a seminary, straight off.”

The Voice of God: “But you have the gift of tongues, my son. You can preach the Gospel in all the lands of Babel. You were born to be a missionary. You say you are young, but time is rushing by you like a whirlwind. Start early, and you will enjoy added years of service.”

The added years of service were so many added tails to the cat repeatedly laid on my back. I can’t see his face now; I never can. Maybe it was because I was always afraid to look at it then.

And years later, when he was dead, and laid out, in black, amidst bouquets, amidst weeping congregationalists, amidst prayers, red faces, handkerchiefs, hands patting your shoulders, solemn faced comforters . . . I looked at him and did not recognize him.

We had met nine months before my birth, this stranger and I. He had never been cruel—stern, demanding, with contempt for everyone’s shortcomings—but never cruel. He was also all that I had had of a mother. And brothers. And sisters. He had tolerated my three years at St. John’s, possibly because of its name, never knowing how liberal and delightful a place it really was.

But I never knew him, and the man atop the catafalque demanded nothing now; I was free not to preach the Word. But now I wanted to, in a different way. I wanted to preach a word that I could never have voiced while he lived.

I did not return for my senior year in the fall. I had a small inheritance coming, and a bit of trouble getting control of it, since I was still under eighteen. But I managed.

It was Greenwich Village I finally settled upon.

Not telling any well-meaning parishioners my new address, I entered into a daily routine of writing poetry and teaching myself Japanese and Hindustani. I grew a fiery beard, drank espresso, and learned to play chess. I wanted to try a couple of the other paths to salvation.

After that, it was two years in India with the Old Peace Corps—which broke me of my Buddhism, and gave me my Pipes of Krishna lyrics and the Pulitzer they deserved.

Then back to the States for my degree, grad work in linguistics, and more prizes.

Then one day a ship went to Mars. The vessel settling in its New Mexico nest of fires contained a new language. —It was fantastic, exotic, and esthetically overpowering. After I had learned all there was to know about it, and written my book, I was famous in new circles:

“Go, Gallinger. Dip your bucket in the well, and bring us a drink of Mars. Go, learn another world—but remain aloof, rail at it gently like Auden—and hand us its soul in iambics.”

And I came to the land where the sun is a tarnished penny, where the wind is a whip, where two moons play at hot rod games, and a hell of sand gives you incendiary itches whenever you look at it.

*

I rose from my twisting on the bunk and crossed the darkened cabin to a port. The desert was a carpet of endless orange, bulging from the sweepings of centuries beneath it.

“I, a stranger, unafraid—This is the land—I’ve got it made!”

I laughed.

I had the High Tongue by the tail already—or the roots, if you want your puns anatomical, as well as correct.

The High and Low tongues were not so dissimilar as they had first seemed. I had enough of the one to get me through the murkier parts of the other. I had the grammar and all the commoner irregular verbs down cold; the dictionary I was constructing grew by the day, like a tulip, and would bloom shortly. Every time I played the tapes the stem lengthened.

Now was the time to tax my ingenuity, to really drive the lessons home. I had purposely refrained from plunging into the major texts until I could do justice to them. I had been reading minor commentaries, bits of verse, fragments of history. And one thing had impressed me strongly in all that I read.

They wrote about concrete things: rock, sand, water, winds; and the tenor couched within these elemental symbols was fiercely pessimistic. It reminded me of some Buddhists texts, but even more so, I realized from my recent recherches, it was like parts of the Old Testament. Specifically, it reminded me of the Book of Ecclesiastes.

That, then, would be it. The sentiment, as well as the vocabulary, was so similar that it would be a perfect exercise. Like putting Poe into French. I would never be a convert to the Way of Malann, but I would show them that an Earthman had once thought the same thoughts, felt similarly.

I switched on my desk lamp and sought King James amidst my books.

Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all if vanity. What profit hath a man . . .

*

My progress seemed to startle M’Cwyie. She peered at me, like Sartre’s Other, across the tabletop. I ran through a chapter in the Book of Locar. I didn’t look up, but I could feel the tight net her eyes were working about my head, shoulders, and rapid hands. I turned another page.

Was she weighing the net, judging the size of the catch? And what for? The books said nothing of fishers on Mars. Especially of men. They said that some god named Malann had spat, or had done something disgusting (depending on the version you read), and that life had gotten underway as a disease in inorganic matter. They said that movement was its first law, its first law, and that the dance was the only legitimate reply to the inorganic . . . the dance’s quality its justification,—fication . . . and love is a disease in organic matter—Inorganic matter?

I shook my head. I had almost been asleep.

“M’narra.”

I stood and stretched. Her eyes outlined me greedily now. So I met them, and they dropped.

“I grow tired. I want to rest for awhile. I didn’t sleep much last night.”

She nodded, Earth’s shorthand for “yes,” as she had learned from me.

“You wish to relax, and see the explicitness of the doctrine of Locar in its fullness?”

“Pardon me?”

“You wish to see a Dance of Locar?”

“Oh.” Their damned circuits of form and periphrasis here ran worse than the Korean! “Yes. Surely. Any time it’s going to be done I’d be happy to watch.”

I continued, “In the meantime, I’ve been meaning to ask you whether I might take some pictures—”

“Now is the time. Sit down. Rest. I will call the musicians.”

She bustled out through a door I had never been past.

Well now, the dance was the highest art, according to Locar, not to mention Havelock Ellis, and I was about to see how their centuries-dead philosopher felt it should be conducted. I rubbed my eyes and snapped over, touching my toes a few times.

The blood began pounding in my head, and I sucked in a couple deep breaths. I bent again and there was a flurry of motion at the door.

To the trio who entered with M’Cwyie I must have looked as if I were searching for the marbles I had just lost, bent over like that.

I grinned weakly and straightened up, my face red from more than exertion. I hadn’t expected them that quickly.

Suddenly I thought of Havelock Ellis again in his area of greatest popularity.

The little redheaded doll, wearing, sari-like, a diaphanous piece of the Martian sky, looked up in wonder—as a child at some colorful flag on a high pole.

“Hello,” I said, or its equivalent.

She bowed before replying. Evidently I had been promoted in status.

“I shall dance,” said the red wound in that pale, pale cameo, her face. Eyes, the color of dream and her dress, pulled away from mine.

She drifted to the center of the room.

Standing there, like a figure in an Etruscan frieze, she was either meditating or regarding the design on the floor.

Was the mosaic symbolic of something? I studied it. If it was, it eluded me; it would make an attractive bathroom floor or patio, but I couldn’t see much in it beyond that.

The other two were paint-spattered sparrows like M’Cwyie, in their middle years. One settled to the floor with a triple-stringed instrument faintly resembling a samisen. The other held a simple woodblock and two drumsticks.

M’Cwyie disdained her stool and was seated upon the floor before I realized it. I followed suit.

The samisen player was still tuning it up, so I leaned toward M’Cwyie.

“What is the dancer’s name?”

“Braxa,” she replied, without looking at me, and raised her left hand, slowly, which meant yes, and go ahead, and let it begin.

The stringed-thing throbbed like a toothache, and a tick-tocking, like ghosts of all the clocks they had never invented, sprang from the block.

Braxa was a statue, both hands raised to her face, elbows high and outspread.

The music became a metaphor for fire.

Crackle, purr, snap . . .

She did not move.

The hissing altered to splashes. The cadence slowed. It was water now, the most precious thing in the world, gurgling clear then green over mossy rocks.

Still she did not move.

Glissandos. A pause.

Then, so faint I could hardly be sure at first, the tremble of winds began. Softly, gently, sighing and halting, uncertain. A pause, a sob, then a repetition of the first statement, only louder,

Were my eyes completely bugged from my reading, or was Braxa actually trembling, all over, head to foot?

She was.

She began a microscopic swaying. A fraction of an inch right, then left. Her fingers opened like the petals of a flower, and I could see that her eyes were closed.

Her eyes opened. They were distant, glassy, looking through me and the walls. Her swaying became more pronounced, merged with the beat.

The wind was sweeping in from the desert now, falling against Tirellian like waves on a dike. Her fingers moved, they were the gusts. Her arms, slow pendulums, descended, began a counter-movement.

The gale was coming now. She began an axial movement and her hands caught up with the rest of her body, only now her shoulders commenced to writhe out a figure-eight.

The wind! The wind, I say. O wild, enigmatic! O muse of St. John Perse!

The cyclone was twisting around those eyes, its still center. Her head was thrown back, but I knew there was no ceiling between her gaze, passive as Buddha’s, and the unchanging skies. Only the two moons, perhaps, interrupted their slumber in that elemental Nirvana of uninhabited turquoise.

Years ago, I had seen the Devadasis in India, the street-dancers, spinning their colorful webs, drawing in the male insect. But Braxa was more than this: she was a Ramadjany, like those votaries of Rama, incarnation of Vishnu, who had given the dance to man: the sacred dancers.

The clicking was monotonously steady now; the whine of the strings made me think of the stinging rays of the sun, their heat stolen by the wind’s halations; the blue was Sarasvati and Mary, and a girl named Laura. I heard a sitar from somewhere, watched this statue come to life, and inhaled a divine afflatus.

I was again Rimbaud with his hashish, Baudelaire with his laudanum, Poe, De Quincy, Wilde, Mallarme and Aleister Crowley. I was, for a fleeting second, my father in his dark pulpit and darker suit, the hymns and the organ’s wheeze transmuted to bright wind.

She was a spun weather vane, a feathered crucifix hovering in the air, a clothes-line holding one bright garment lashed parallel to the ground. Her shoulder was bare now, and her right breast moved up and down like a moon in the sky, its red nipple appearing momentarily above a fold and vanishing again. The music was as formal as Job’s argument with God. Her dance was God’s reply.

The music slowed, settled; it had been met, matched, answered. Her garment, as if alive, crept back into the more sedate folds it originally held.

She dropped low, lower, to the floor. Her head fell upon her raised knees. She did not move.

There was silence.

*

I realized, from the ache across my shoulders, how tensely I had been sitting. My armpits were wet. Rivulets had been running down my sides. What did one do now? Applaud?

I sought M’Cwyie from the corner of my eye. She raised her right hand.

As if by telepathy the girl shuddered all over and stood. The musicians also rose. So did M’Cwyie.

I got to my feet, with a Charley Horse in my left leg, and said, “It was beautiful,” inane as that sounds.

I received three different High Forms of “thank you.”

There was a flurry of color and I was alone again with M’Cwyie.

“That is the one hundred-seventeenth of the two thousand, two hundred-twenty-four dances of Locar.”

I looked down at her.

“Whether Locar was right or wrong, he worked out a fine reply to the inorganic.”

She smiled.

“Are the dances of your world like this?”

“Some of them are similar. I was reminded of them as I watched Braxa—but I’ve never seen anything exactly like hers.”

“She is good,” M’Cwyie said. “She knows all the dances.”

A hint of her earlier expression which had troubled me . . .

It was gone in an instant.

“I must tend my duties now.” She moved to the table and closed the books. “M’narra.”

“Good-bye.” I slipped into my boots.

“Good-bye, Gallinger.”

I walked out the door, mounted the jeepster, and roared across the evening into night, my wings of risen desert flapping slowly behind me.