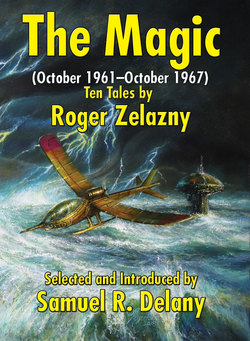

Читать книгу The Magic (October 1961–October 1967) - Roger Zelazny - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

III

Оглавление“Not El Greco; nor Blake, no: Bosch. Without any question, Bosch—with his nightmare vision of the streets of hell. He would be the one to do justice to this moment of the storm.”

This is the story of “Godfrey Justin Holmes—‘God’ for short,” and whose nickname is “Juss . . . ” who has come to a watery world, and its single continent, “Terra del Cygnus, Land of the Swan—delightful name.

“Delightful place, too, for a while . . . ”

Juss is a Hell Cop, a lookout with a hoard of 135 remote control eyes, which look over what at first seems to be a peaceful land, but as a great storm—far greater than any known on earth—raises up about the landscape a hoard of monsters in the streets. (“They say the job title comes from the name of an antique flying vehicle—a hellcopper, I think.”) In this story, Zelazny’s first person narrator returns to a cryogenic technique we last saw in “The Graveyard Heart,” only here strung out to become the way to accomplish interstellar travel at slower than light speeds.

People smoke regularly—risking cancer. (It is what killed Zelazny in 1995 at the age of 58.) In the same story at one point sickness is said to come from “dampness” and “from cold,” which is tantamount to earmarking the story as originating from before the increased awareness, which arrived with the age of AIDS, that sicknesses come from viruses and bacteria and that dampness, cold, and malnutrition can only lower one resistance to disease. Even dirt does not spread disease itself, if the proper pathogens are not present. The bag of hydrochloric that hangs at the bottom of the esophagus, commonly known as the belly, is not only an early step in the digestion process, it is also an early step in the immune system’s fight against the pretty much ninety-five percent of all viruses and bacteria that might harm the human machine itself.

“Where are the rains of yesteryear?” Zelazny riffs on the line by Villon, “Ou sont les nieges . . . ”

And another one of his Immortals moved off onto an uncertain future threaded across the stars: “Years have passed. I am not really counting them anymore. But I think of this thing often: Perhaps there is a Golden Age someplace, a Renaissance for me sometime, a special time somewhere, somewhere but a ticket, a visa, a diary-page away. I don’t know where or when. Who does? Where are all the rains of yesterday?

“In the invisible city?

Inside me . . . ?”

And in two more necessary sentences the story is done.

*

I seem to remember an editorial blurb at the beginning of Zelazny’s story “This Mortal Mountain” that first appeared in the March 1967 edition of Worlds of If that said, in effect, that, as Dante knew, at the end of everything, there are stars. (John Ciardi’s very serviceable translations of all three parts each ends with the word “stars.”) This is a story about climbing the mount of Purgatory, and ironically, it begins with the protagonist, Jack Summers, looking down on that seven-tiered mountain from a space ship:

“A forty-mile-high mountain,” I finally said, “is not a mountain. It is a world all by itself which some dumb deity forgot to bring into orbit.”

The prospect of an ascent up the highest mountain in the explored section of the galaxy inspires Jack Summer to summon his posse from among the stars: Doc and Kelly and Stan and Mallardi and Vincent.

The discovery is that, at the top, is a woman who has been put into a sort of suspended animation who suffers from something called Dawson’s Plague, by her husband (whose name was Carl, which is incidentally the name of the protagonist of “The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth”), before he died. Illusions begin to confront them announcing that they should go back, in between other communications.

As Zelazny remarks, Dante had located the Earthly Paradise—Eden—on the top of Mount Purgatory (on the top level devoted to the Lustful). To go on beyond that point requires a miracle.

As they get closer and closer to the top, the mountain begins to look more and more like a Nordic version of a Night on Bald Mountain, with a three-headed dragon encircling its highest peak.

The seven chapters of the novelette correspond to the seven terraces that circle Dante’s Mount of Purgatory, with the seven deadly sins that become more and more forgivable: pride, envy, ire, sloth, greed, gluttony, and finally lust or eros:

The first chapter of the story establishes Jack Summer (Whitey) as the man who has climbed all the other great mountains in this universe, including Mt. Kasla on Litan, at 89,941 feet. As well, we learn that world, wherever it is, has a thin atmosphere, because the ceiling on a jet is 30-thousand feet, and the mountain is higher than that. And the beginning of the second chapter he sends out his call for his crew to join him: “If you want in on the biggest climb of all, come to Diesel. The Gray Sister eats Kasla for Breakfast.

The gravity of the planet is a little weaker. (“On Diesel, the pack and I together probably weighed about the same as me alone on Earth—for which I was grateful.”) And as he does his early exploring of the mountain from the north face, now and again he hears the voice in his mind that says, “Go back.” If there is envy, it would seem to be of the solidity of the mountain itself. In three days, we are told (in the way only science fiction can do), he has gotten higher than Everest—and that, indeed, on other islands nearby there are 12 and 15 mile high mountains, but nothing like the Gray Sister (a.k.a. The Lady).

Chapter III (which we might expect to be devoted to Ire) turns out to be the section that contains what first appears to be a burst of lyric madness; when his friends come and Whitey/Summer meets with them by themselves, he offers the proof that makes the story actually science fiction—a charred back pack he turns out to have brought back with him from his preliminary climb on the mountain while he was waiting for his crew to assemble. “Ire” is replaced by “Intelligence.”

(It recalls a moment from Disch’s Camp Concentration when the imprisoned poet Louis Sachetti recalls how his priest in his childhood would warn him to be beware of “Intellectual Pride,” which Sacchetti finally decided was just a warning to deride intellect.)

Chapter IV finds the crew planning, mapping, charting, and studying photos—the only nod to “sloth” is that “Henry was on his way to fat,” and that Doc and Stan, while in good condition, had not climbed in a while.

In the course of this section, Summer meets with an embodied hallucination from the mountain—a woman—and the section ends with talk of tiredness and exhaustion.

Greed, Gluttony, and Lust lie ahead; and chapter V begins with two days of steady progress. (“We made slightly under ten thousand feet,” pp 490.) They have made their way to the western side, where they break ninety thousand feet and stop “to congratulate ourselves that we had surpassed the Kalsa climb and to remind ourselves that we had still not hit the halfway mark.” That takes them another two-and-a-half days.

A new hallucination materializes, then, which they all see: “the creature with the sword.” Bits of logic are scattered throughout the tale:

The fires from the hallucination do not melt the ice it sits on. So the men can agree that, indeed, a hallucination is what it is. Things get colorful with scarlet serpents. “Rocks still fell periodically, but the boss seemed to be running low on them. The bird appeared, circled us and swooped on four different occasions. But this time we ignored it, and finally it went home to roost.”

In Chapter VI (in which easily we might look for marks of gluttony), we find such statements as: “How does a man come to climb mountains? Is he drawn to the heights because he is afraid of the level land? Is he such a misfit in the society of man that he must flee and try to place himself above it? The way up is long and difficult, but if he succeeds they must grant him a garland of sorts. And if he falls, this too is a kind of glory. To end, hurled from the heights to the depths in hideous ruin and combustion down is a fitting climax for the loser for it too shakes mountains and minds, stirs things like thoughts below both is a kind of blasted garland of victory in defeat, and cold, so cold that final action that the movement is somewhere frozen forever into a statue-like rigidity of ultimate intent and purpose, thwarted only by the universal malevolence we all fear exists.” The text has moved from a contemplation of the seven deadly sins to the classical problem of hubris itself.

“I had known that I had to climb Kasla as I had climbed all the others, and I had known what the price would be. It cost me my only home. But Kasla was there, and my boots cried out for my feet. I knew as I did so, that somewhere I set them upon her summit and below me a world was ending.” The world that is ending is the world in which the mountain has not been climbed, and the world that is beginning is the one in which the mountain has been conquered, and Jack Summer, a.k.a. Whitey, is the hero who has conquered it.

The climbers reach a hundred seventy-six thousand feet, making their way along a ledge, till one member of the climbing crew, Vince, calls out, “Look!”

Up and up, and again further, blue-frosted and sharp, deadly and cold as Loki’s dagger, slashing at the sky, it vibrated above us like electricity, hung like a piece of frozen thunder, and cut, cut, into the center of spirit that was desire twisted and become a fishhook to pull us on, to burn us with its barbs.

Vince was the first to look up and see the top, the first to die. It happened so quickly and it was none of the terrors that achieved it.

He slipped.

That was all. It was a difficult piece of climbing. He was right behind me one second, was gone to the next. There was no body to recover. He had taken the long drop. The soundless blue was all around him and the great grey beneath. Then we were six. We shuddered and I suppose we all prayed in our own ways.

In the morning, one more crew member is gone:

“So we were five—Doc and Kelly and Henry and Mallardi and me—and that day we hit a hundred and eight thousand and felt very alone.” (It suggests Kafka’s parable “Fellowship”: “We are five friends . . . and cannot be tolerated with this sixth one.”) Once more the hallucination of the woman joins them. There is a conversation in which she seems strangely present and absent at the same time. “Why do you hate us?” Jack Summer asks.

“No hate, sir,” she said.

“What then?”

“I protect.”

“What? What is it that you protect?”

“The dying, that she may live.”

“What? Who is dying? How?”

But her words went away somewhere, and I did not hear them. Then she went away too and there was nothing left but sleep for the rest of the night.

They climb for another week.

“I’m not worried about making it to the top,” Henry says. “The clouds are like little wisps of cotton down there.”

The purgatorial allegory results with approach of the uppermost level of the lustful—only the woman involved is as cold and stony as Leota Mathild Mason in cold-sleep in “The Graveyard Heart.”

What the text recalls even more than the ascent of Purgatory is Sigfried breaking through the circle of fire surrounding Brunhilde, with the flames themselves taking on the aspect of demons and dragons.

I left Henry far below me. The creature was a moving light in the sky. I made two hundred feet in a hurry, and when I looked up again. I saw the creature had grown two more heads. Lightnings flashed from its nostrils, and its tail whipped around the mountain. I made an another hundred feet, and I could see Mallardi clearly by then, climbing steadily, outlined against the brilliance. I swung my pick, gasping, and I fought the mountain, following the trail he had cut. I began to gain on him because he was still pounding out his way and I didn’t have that problem yet. Then I heard him talking:

“Not yet, big fella, not yet,” he was saying, from behind a wall of static. “Here’s a ledge . . . ”

I looked up, and he vanished.

The seventh and final section—the entrance into the cave at the mountain top—replays the entrance into the cold-sleep bunker at the end of “The Graveyard Heart” without the Grand Guignol of the stake through the heart/womb. The disease Linda’s husband—Carl—is trying to help her survive until it is cured is something called Dawson’s Plague.

A death . . .

A life . . .

A lot of technological hugger-mugger . . .

At the top of a mountain whose peak is forty-two miles high, above the atmosphere itself. Clearly Zelazny is aware of the Puragotrial allegory. (“Tell me what it was like to climb a mountain like this one. Why?”

(“There is a certain madness involved,” I said, “a certain envy of great and powerful natural forces, that some men have. Each mountain is a deity you know. Each mountain is an immortal power. If you make sacrifice upon its slopes, a mountain may grant you a certain grace, and for a time, you will share its power.”)

I think the key to why “Damnation Alley” is less effective than it might be is in Zelazny’s own note: “I wanted to do a straight, style-be-damned action story with the pieces fall[ing] wherever.” Well, when the style is let go, the truth is there’s not that much left to a Zelazny tale—though the results are still interesting.

Zelazny’s own comments on the movie is instructive: there were two scripts, the first of which he was shown, and which was much better than the second which they actually used. It recalls Lessing’s characterization of genius: the ability “to put talent wholly into the service of an idea,” which is what the flexibility of voice that Zelazny’s strives for in his various styles accomplishes in the passages where the style is most in evidence:

The stories, such as the ones here, where the full toolbox is used most artfully.

And that is why one should continue to read him.

—Friday, February 8, 2018,

Philadephia, PA.