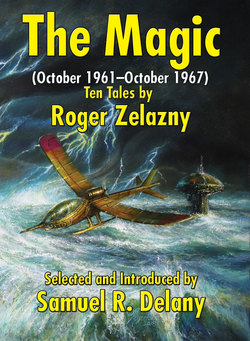

Читать книгу The Magic (October 1961–October 1967) - Roger Zelazny - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Zelazny!

Оглавлениеby Samuel R. Delany

In 1938, in what is probably one of the best books on writing I’ve ever read, Cyril Connelly wrote, “Those whom the gods would destroy, they first call promising.”

Though I was not to hear of it till many years later, both Zelazny and I had early high school stories published in a national magazine called Literary Cavalcade—Roger’s was a short–short called “Mr. Fuller’s Revolt,” from Vol. 7, October 1st, 1954.

A year before Connelly’s Enemies of Promise appeared, Zelazny (May 13, 1937–June 14, 1995) was born in Euclid, Ohio.

In the October1965 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction the first half of his serialized novel . . . And Call Me Conrad appeared.

A young woman friend of mine named Ana Parez brought the issue to my apartment on East 7th Street, to show me. Ana was a folksinger, who, when I first met her, had been a student at the Bronx High School of Science, who had recently come from Boston Latin. When she arrived at Seventh Street, she explained: “This is it, what I told you about on the phone. Chip, who is this guy?” And that night I read it, and by the end I wanted to read not only the rest but everything he wrote or had published. And shortly I was able to find the November 1963 issue (with the glorious Hannes Bok cover) and read the first of the stories here, “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” (which would later be revealed to have been written a year before his first two professional sales, “Horseman” in the August 1962 issue of Fantastic and “Passion Play” in the August 1962 issue of Amazing). There is something about the early stories of Roger Zelazny that makes you want to analyze how they work, because they work so well.

I wanted to meet him, and that year I went to my first SF convention, the Tricon, in Cleveland, Ohio, where . . . And Call Me Conrad tied for the Hugo Award with Frank Herbert’s Dune! (For a while, in manuscript, Zelazny's novel had born three titles, typed or handwritten: I Am Thinking of My Earth, and Good-Bye, My Darling, Good-Bye, Conrad had been rejected; finally, . . . And Call Me Conrad, one of the handwritten ones, had—happily!—been chosen.) I recall sitting in the audience when the professionals who were in attendance were announced, and how we all applauded the known names when they came up. Zelazny’s name received an incredibly enthusiastic, standing ovation—the only writer there who did, and—unlike the others—it went on and on and on . . .

I stood too, and felt good that I was there to applaud with the rest, and that, as well, I was lucky enough to belong to such a community that recognized the excellence of this writer. (I had read enough of Dune to know that, while I approved of what I had picked up as its ecological message, it was an unreadably poor novel and homophobic to boot.) That weekend, I sought out Roger (my own sixth novel, Babel-17, had been nominated for a Nebula Award), and he was free for dinner, and I was lucky enough to dine that night with him and his wife, Judith, at the hotel restaurant. We were both enthusiastic about each other’s work, and I recall we reached our table over a transparent bridge above a fish pond in the floor, and we agreed that it looked like something one might find in an Alfred Bester novel. I also seem to remember that Judith said she didn’t find science fiction that interesting, but that since everybody here seemed to like what Roger wrote, she guessed it was good. As early as 1968, three years after . . . And Call me Conrad, I knew the stories I wanted to see together in this book. (One of his most satisfactory novels, Doorways in the Sand [1976] was still to come.) When, once again, we got a chance to sit down for a few moments together (in Baltimore?), I told him, “I didn’t think ‘Damnation Alley’—” which had been nominated for a Hugo award—“worked as well as it might.” He grimaced a little.

“Actually,” he said, “I didn’t think so either, Chip. But it’s good to know you cared.”

That was the last time we ever spoke directly, though we were in touch in other ways. In ’68 in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction published my loving pastiche of what I felt to be Zelazny at his best, whose hero was a more realistic and, I hoped, a more heroic version of Hell Tanner. Only in 2012, did I hear—through a Facebook chat box of all places—Bruce Chrumka report “I once asked R. Zelazny what he thought of “We, in some Strange Power’s Employ, Move on a Rigorous Line,” [ . . . and] he said he loved it and wished he’d written it. This was in front of perhaps 300 conventioneers in Edmonton, [Canada, in] the late ’80s.”

Although I didn’t learn this until five years ago (twenty-two years after Roger’s death), it was a high compliment.

When, in mid-June of 1995, Roger died in New Mexico of cancer, my old student, George R. R. Martin, phoned me with the news and also told me that Roger had wanted me to know he was thinking of me—another high compliment.

However lightweight I found some of the Amber novels that came to dominate Zelazny’s output, through the 1970s, I could already reel off what I felt were Zelazny’s strongest stories from his early works, which—if they were collected in a single volume—would foreground his strengths as a writer and storyteller: “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” (1961, pub 1963), “The Ides of Octember” (a.k.a, “He Who Shapes,” 1965), “The Graveyard Heart” (1964), “The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of his Mouth” (1965), “The Furies” (1965), “The Keys to December” (1966), “For a Breath I Tarry” (1966), “This Moment of the Storm” (1966), “This Mortal Mountain” (1967), and the already discussed “Damnation Alley” (1967).

Both “The Ides of Octember” (under its alternate title) and “The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth” won Nebula Awards as best long stories (novella and novelette) of their respective years.

An amazingly bad film was made “from” Damnation Alley, about which neither Zelazny nor I had anything to say at all. (I have to put “from” in quotes: The film’s plot has nothing to do with Zelazny’s tale, and then some special effects are added that have nothing to do with anything.) In his note on the story, Roger makes the point that the main character grew out of conversations with a real person (he does not tell us who), who actually rode a motorcycle, which is revealing; as he says, it’s the only story he ever wrote in which this was the case. In the same note, he reveals his intention: “I wanted to do a straight, style-be-damned action story with the pieces fall (sic) wherever. Movement and menace. Splash and color is all.”

Writers be warned: adventure, psychology, and even comprehension are before all else affects. It’s impossible to achieve any of the three without at least grammar, whether acceded to or violated, or style of some kind under some control. Hell Tanner’s realness produces only banality and an unearned confidence in the material that the reading experience doesn’t support.