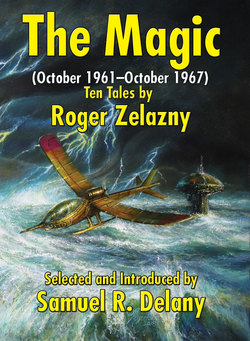

Читать книгу The Magic (October 1961–October 1967) - Roger Zelazny - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

When Zelazny was Magic

Оглавлениеby Darrell Schweitzer

I remember when Roger Zelazny was magic. This is not to say that he was ever anything but an accomplished, fine writer or that he ever lacked an audience, but there was a period, around 1964–1970, when he was magic, and every new story of his was an event. He was a tremendously variable writer too, so that each event was not like the past one. “He Who Shapes” serialized in Amazing was very special indeed, a mind-blower. Not at all like the novella “Damnation Alley” in Galaxy a couple years later. Not at all like “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” or “The Graveyard Heart.”

I enter the scene in the spring of 1967. Probably the first Zelazny story I ever read was “This Mortal Mountain” in the March IF. I then read “Dawn,” an excerpt from the forthcoming Lord of Light, in the April F&SF. Then came “The Man Who Loved the Faoli” in the June Galaxy. This last, I realized later, a particularly remarkable achievement for Zelazny. The story was written around a cover, a painting by Gray Morrow which showed rectangular-bodied, tentacled robots wading through a valley of dry bones beneath a strange sun. This was clearly a reject or leftover from the Ace Books printings of Neil R. Jones’s Professor Jameson series. (The “robots” were the star-traveling Zoromes. The professor’s brain was housed in one of them.) This orphaned painting was shuffled over to Galaxy and then a popular contributor was given the assignment of writing a story around it, as was a common editorial practice at the time. But where most writers would have just typed some squib, Zelazny wrote a story which seemed, to me at least, stunningly beautiful.

Zelazny was a name I learned to watch for.

I was a little short of fifteen in June of 1967. I remember writing an excited high-school paper (possibly a couple years later) about the works of Roger Zelazny. I don’t think my English teacher was too thrilled. He tended to discourage any interest in popular or imaginative literature, particularly science fiction. But Zelazny was the first writer who made me aware of the possibilities of prose.

He had style.

This was, in science fiction fandom, the era of the New Wave Wars. We talked about “style” a lot. Zelazny was claimed by both sides, but he certainly had style.

It was easy to imitate.

Lots of short sentences.

Asterisk breaks.

*

And a flourish of something you hoped was “poetic.”

I wrote Zelazny imitations. I even sold a couple. I picked up on the concept we see in “The Keys to December” and “The Graveyard Heart” about a pair of lovers who go on through the ages, out of sync with everybody else, living a few years (or days) every century. I did it with time-dilation. But of course the difference between a Zelazny imitation by an apprentice writer and a real Zelazny story is like the difference between a kid in a garage band trying to sound like the Beatles and the actual Beatles. About the same time I received a review copy of a book from Doubleday, The Exile of Ellendon by William Marden (1974) which was very clearly somebody else’s attempt to write a Zelazny novel and published by Zelazny’s own publisher presumably on the assumption that it would sell to the same audience. I don’t blame Marden, certainly. He was no doubt as Zelazny-struck as I was.

Imitating Zelazny is easy to do.

But it won’t be the real thing. Art conceals art, and all that.

What Zelazny did was considerably more complex and accomplished. Which does bring us back to the story I am supposed to be commenting on, “The Keys to December.”

I read this one much later, either in the collection The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth (1971) or in New Worlds as by that point I had mastered the art of acquiring used science fiction, even from overseas, and those paperback-sized, Compact Books New Worlds (early Moorcock issues) were easy to get. This story had no American periodical appearance, but Zelazny, as a “new wave” writer, was a regular in New Worlds in those days, before he was summarily drummed out in early 1968 (presumably for the crime of being too popular; you can’t be a rebel underdog if you are successful) with a nasty, trashing review of Lord of Light, which signaled that he would never appear there again.

This is another story that makes language sing. Its prose jumps through hoops. The 300-word description of a planet gives us a hint of what Zelazny is capable of. The concept of this story could have come out of the 1950s. Think of the pantropy stories (collected as The Seedling Stars) of James Blish, or Poul Anderson’s “Call Me Joe.” Then it would have been about tough, not-quite human pioneers struggling to make it on a planet to which they had been adapted. There would have been a lot of technical detail. I can envision that Kelly Freas cover, from mid-’50s Astounding. Would the central moral dilemma of the story have been addressed in the 1950s in Astounding? Yes, probably. How about the religious aspect, with the hero becoming a god to the natives and (one gets a sense) almost enjoying it? Maybe, but probably not. That is something Philip José Farmer might have edged toward, but not in Astounding. (Farmer never wrote for Astounding.) But certainly none of those writers would have described “stands of windblasted stones like frozen music.”

There are elements here we see elsewhere in Zelazny. The essentially alienated protagonist. The background of an interstellar capitalism that enables people or corporations to buy planets. Men who become gods. (Think of Francis Sandow in Isle of the Dead.) The myth elements are here, not in this case a replaying of something out of past Earth literature and religion, but a myth that is coming to being due to Jarry Dark’s intervention with the natives. His combat with the bear-thing will surely be retold down the generations and become the stuff of epics. The death of Sanza will become a deep Mystery, possibly to be re-enacted in mysterious rites, millennia in the future. The reader may be at first disturbed by what the December group is doing. They are of course, the invaders from space, changing the planet to their liking, to the detriment of the natives. There is no overt slaughter. There doesn’t need to be. But the invasion is more extreme than that described in H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. About this same time (1965) Thomas M. Disch imagined aliens completely transforming the Earth for their own purposes. He called it The Genocides.

That the Worldchange machines are forcing the native lifeforms to evolve sounds like a corporate excuse. That this actually happens is intriguing, and of course it triggers the final crisis. Zelazny has not overlooked the moral implications of what is going on. Not all science fiction is that thoughtful. I remember reading a story in Analog once, by Christopher Anvil (“The Royal Road,” June 1968), in which the superior Earthmen induce the benighted natives to labor long and hard, at the cost of immeasurable suffering and death, to build a massive, completely useless structure. When it is complete, we are told this was for their own good, because it united them with a sense of purpose and prevented wars, or some such nonsense. Of course the paternalistic humans decided what was for the natives’ own good. Vile.

Zelazny is better than that. His character has to take radical action, then assume responsibility for what is happening. His is a far more nuanced, ambiguous solution. Yes, of course, this is one of the countless science fictions stories that prefigure the 2009 film Avatar. Its moral balance is considerably less black and white.

But mostly what we notice about this story is the style. Zelazny’s voice, then and later, was unique. His prose sang. It still sings.