Читать книгу Flowers Cracking Concrete - Rosemary Candelario - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Walking into Wesleyan University’s Zilkha Gallery for the launch of Eiko & Koma’s Retrospective Project, I almost feel as if I am backstage at a theater rather than at the opening of an exhibition. A massive, sand-colored canvas hanging from the ceiling reinforces my perception of being behind the scenes. Upon closer inspection, the burnt surface offers me small windows through which I may catch glimpses of the gallery beyond. Students, many of them from Eiko’s Delicious Movement for Forgetting, Remembering, and Uncovering class, busily rush past me, taking care of last-minute tasks. Small attentive groups, including then American Dance Festival director Charles Reinhart, Retrospective Project producer Sam Miller, and former Japan Foundation director of performing arts Paula Lawrence, gather in front of video screens behind me displaying the video compilation, 38 Works by Eiko & Koma, which cycles through documentation of the duo’s dances since they came to the United States from Japan in 1976. The energy of the crowd pulls me further down the hallway, past a table set up with a computer displaying Eiko & Koma’s new Web site, and toward backdrops from Cambodian Stories (2006) that grace the walls. Just as the paintings by students at Reyum School of Art in Phnom Penh begin to tower over me, I notice my feet are crunching dry leaves; am I supposed to be walking here? Instead of ending at a wall, this hallway has led me into the leafy, dimly lit cave that is the set of Breath, Eiko & Koma’s 1998 live installation at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Although I feel I could stay in this environment for hours, sounds from the main gallery draw me back toward the scorched and scarred canvas. Stepping around it, I find myself literally onstage, facing rows of empty chairs, soon to be filled by the more than one hundred attendees. I am standing on the black-feather-and straw-strewn set for Raven (2010), which will have a preview performance in just a few moments. Gazing around the high-ceilinged, long room, I am first struck by the media dances filling the near wall. In one, Eiko & Koma’s naked bodies seem to float midair, sorrow dripping from their bodies, in Lament (1985), while on a nearby cracked and peeling screen, Eiko & Koma raise a white flag of surrender in documentation of Event Fission (1980). Opposite, the wall is all glass, providing a view of the trailer from Eiko & Koma’s Caravan Project (1999); standing open as it did during site-specific performances all over the United States, its fiery interior is mirrored by a blanket of crimson leaves on the ground and the sun setting through bare trees. Beyond the chairs at the far end of the gallery hangs a mysterious, speckled black canvas, in front of which Eiko & Koma will end the evening with a revival of their first piece of set choreography, White Dance (1976). Wending its way around the perimeter of the gallery is a thread of snapshots at eye level. This literal time line is paradoxically not linear; when I reach the end, I have somehow returned to the beginning. In addition to images of well- and lesser-known works by Eiko & Koma, I spot photos of the dancers with Kazuo Ohno, Manja Chmiel, and Anna Halprin. One photo from the time line also circulates around the gallery on homemade T-shirts worn by Irene and Paul Oppenheim, the producers of Eiko & Koma’s very first performance in the United States in 1976.

Time Is Not Even, Space Is Not Empty opened on November 19, 2009, and launched the three-year Retrospective Project through which Eiko & Koma aimed to examine their body of work for its continued or shifting resonances for contemporary audiences. The Retrospective gave Eiko & Koma the opportunity to rigorously examine their own practice through the collection (and sometimes production) of archival materials and the creation of new works from earlier dances. Aspects of the Retrospective included museum exhibitions of photographs, sets, and screen dances; a new living installation, Naked (2010); the reworking of older pieces into new dances, for example Raven from Land (1991); the revival of older works; the publication of a retrospective catalog by the Walker Art Center; and a new collaboration with Kronos Quartet, Fragile (2012).

For audience members, the Retrospective showcased the remarkable scope of Eiko & Koma’s body of work. Since meeting at Tatsumi Hijikata’s Asbestos Hall in Tokyo in 1971, Eiko & Koma have choreographed dances that for all their simplicity grapple with monumental matters: destruction and regeneration, relationships among humans and between humans and nature, and the stakes of being an artist in challenging political times. Their work is deeply informed by their participation in the 1960s Tokyo student movement; formative encounters with Hijikata and Ohno, key figures of the avant-garde postwar dance form butoh in Japan; relationships with Mary Wigman assistant Manja Chmiel, Jose Limón dancer Lucas Hoving, and San Francisco iconoclast Anna Halprin; and participation in the New York City arts community. These touchstones—radical politics in postwar Japan, butoh, “Neue Tanz,”1 and downtown dance—are the foundations of Eiko & Koma’s more than four-decades-long collaboration. From these influences, Eiko & Koma developed a singular performance technique and approach to choreography. Though they are considered part of a generation of American dance artists that includes David Gordon, Bebe Miller, and Ralph Lemon, their unique movement style, unrelated to modern dance or ballet; rejection of a company model; insistence upon choreographing almost exclusively on their own bodies; and do-it-yourself practices set them apart from their peers in American concert dance. The Retrospective drew attention to their impressive intersections with dance history on three continents and highlighted the skill with which they move from proscenium stages, to outdoor sites, to museum installations, and in front of and behind the camera.

Eiko & Koma’s Retrospective Project also issued a vivid reminder that the two dancers have been central figures in the American concert dance scene since they moved to New York from Tokyo in 1977. But it also raised important questions, such as why so little academic research exists on Eiko & Koma, despite prestigious recognition by the MacArthur Foundation and the Doris Duke Performing Artist Award, among many others; international renown; and overwhelming critical acclaim.2 Dance reviews constitute the largest body of writing on the pair, including early and sustained attention from noted American critics including Jack Anderson, Suzanne Carbonneau, Jennifer Dunning, Deborah Jowitt, Anna Kisselgoff, Janice Ross, Lewis Segal, and Tobi Tobias. Another important collection of writings is by Eiko herself, comprising choreographer’s notes available in programs and on their Web site, and published essays.3 Academic writing is limited to two master’s theses4 and my own published materials. A couple of books include chapters on Eiko & Koma in the form of interviews or expanded encyclopedia entries.5 The Walker Art Center’s 2011 catalog, Time Is Not Even, Space Is Not Empty, is the most significant text on Eiko & Koma to date, comprising a comprehensive biography, artistic essays, and descriptions of every piece made by the pair from 1972 through 2010. Richly illustrated with photographs and including writings by some of the photographers who have worked with them for decades, the catalog is a major document. Useful appendices include information on funders, commissioners, and presenters from 1972 to 2011.6

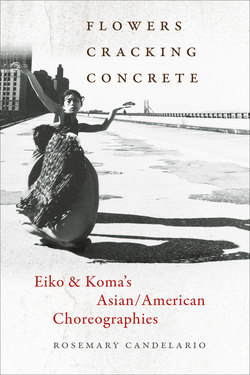

Flowers Cracking Concrete: Eiko & Koma’s Asian/American Choreographies does not attempt to duplicate the contributions of previous texts, but instead provides the first book-length critical analysis of the Japanese American duo’s body of work, examining in detail more than half of their sixty-plus stage, outdoor, video, installation, and gallery works created over more than four decades. This long overdue study argues that Eiko & Koma’s dances, like the flowers of the title, effect a gradual but profound transformation that has significant political implications. I trace the elaboration over time of the concerns that have become central to Eiko & Koma’s work: the linkages between humans and nature, sustained mourning for personal and historical traumas, and the sometimes-fraught alliances among humans. My goal is to intervene in how these dances are viewed by providing historical and political contexts for the development of Eiko & Koma’s choreography in Japan, Europe, and New York City. These contexts place Eiko & Koma firmly in American dance history even as they reveal the necessity of considering the duo as both Japanese and Asian American.

Adagio Activists

An extraordinary—and defining—facet of Eiko & Koma’s work is the slowness with which they unfold their bodies and their dances, a pace less human and more geologic. Moving at a speed significantly decelerated from daily life, Eiko & Koma’s dances shift attention to the ways that seemingly fixed elements of our world—trees, mountains, continents—are also constantly changing. The title of this book, Flowers Cracking Concrete,7 signals the profound corporeal and affective work of Eiko & Koma’s dances. This impossible-seeming image conveys a slow yet violent process effected through persistent and insistent micromovements and embodies the contradictions inherent in Eiko & Koma’s work. Though commonly described as slow and subtle, the effect of Eiko & Koma’s performances is like water eroding rock or tree roots displacing a sidewalk: the sometimes imperceptible movements of two bodies over time have a profound impact physically and emotionally on one another, their environment, and their audiences. Watching them perform, one may think that nothing in particular is happening until—gasp!—one is hit with a realization that something significant—a major shift, a rupture—has transpired. Not only have their drawn-out moving images compelled audiences to pay a different kind of attention, but they have also effected a transformation: slowly, imperceptibly, and then suddenly all at once. Although the dances do include moments of explosive movement, stuttering limbs, and sudden shifts, overall they are marked by an extraordinary insistence on taking time and an attention to the importance of the smallest of movements.

Slavoj Žižek argues persuasively that it is a political choice to do nothing, and that doing nothing is in fact still doing something.8 For Eiko & Koma it is a striking choreographic choice. Of course Eiko & Koma do not do nothing. Even when they seem to an audience to be utterly still, for minutes or hours on end, they are always active. Eiko & Koma’s appearance of doing nothing, of taking their time, of taking space to take time, results in the central mission of their dance slowly revealing itself, both over the course of one performance and over the forty-plus years of their danced collaboration. Slowness then is not just an aesthetic for the stage, but also a method of working over the long term. Moreover, in that they are often doing the same thing, it may appear as if they are doing nothing (new). And yet their stubborn persistence, their insistence upon returning again and again to the same themes and the same movements, demonstrates an extraordinary commitment to taking their time to find out what is important to them and giving that issue physical form.

What stood out to critics who first saw Eiko & Koma’s choreography in the mid- and late 1970s, and continues to be the case into their fifth decade of work, is the surprising effect of their minimalist movement. Critics may have disagreed about the meaning of various performances, but they agreed on the work’s impact. Unfortunately most critics have not probed the dancers’ slowness further, often leaving it at the simple fact of slowness. (“Eiko and Koma Slow Time Down” and “The King and Queen of Slow Get Busy” are representative headlines.9) Their speed, or lack of it as it were, moreover leads some to make Orientalist associations with noh or Zen rock gardens. Many audience members assume Eiko & Koma meditate before performing, as evidenced by the regularity of questions about meditation and yoga at after-performance talk backs. Reviews often neglect to mention the moments of absurdity or outbursts of speed or violence that frequently puncture their dances, leaving unexamined the implications of taking longer than expected to start dancing, to stop mourning, and to form connections.

In order to intervene in the prevailing misreading of Eiko & Koma’s aesthetic of slowness, I emphasize Eiko and Koma’s backgrounds as student activists and the context of the Japanese avant-garde. As I discuss in chapter 1, Eiko and Koma each came to avant-garde performance as student activists in the early 1970s in Japan. Searching for an alternative to what they saw as the dead end of the leftist political scene, they found in dance a compelling way of acting in the world. Rather than seeing their transition from protesting in the streets to performing in galleries and theaters as a break with activism, I see it as a continuation of their critical stance in a new medium. Thinking about Eiko & Koma’s choreography as a kind of activism requires a shift from focusing on what the dances signify to paying attention to what they do. I am not suggesting that Eiko & Koma’s work is beyond representation or signification. Nor am I suggesting that the meaning of these dances cannot be expressed in words. On the contrary, this book challenges such beliefs, insisting instead on articulating the specific ways Eiko & Koma’s choreography actually effects something in the world. Eiko & Koma do not represent mourning, I argue; they do it. They do not just represent new kinds of alliances with nature and across difference; they generate them. Very slowly.

Previously I wrote about the ways Eiko & Koma’s work generated what I called “spaces apart” through the choreographed relationship among moving bodies, sites, and technologies.10 I argued that it is in these spaces apart where alternatives to the dominant society may be rehearsed, and entrenched binaries such as nature/culture and East/West may be challenged. In this book I focus on time as a foundational concept, particularly the passage of time as conveyed through the concept of slowness. Specifically, I frame Eiko & Koma’s choreography as an adagio activism. This term is inspired by Žižek’s insight into what slowing down can achieve.11 He writes,

“Do you mean we should do NOTHING? Just sit and wait?” One should gather the courage to answer: “YES, precisely that!” There are situations when the only truly “practical” thing to do is resist the temptation to engage immediately and to “wait and see” by means of a patient critical analysis.12

Looking back at Eiko & Koma’s body of work over the past forty years, it becomes evident how they have used their dances as an opportunity to continuously analyze with their bodies the issues most important to them. In a 1986 interview, Eiko shared, “We do not want to jump into working on a dance with a concept which is just hunted. It should be some theme that slowly comes up as a concern, which we cannot help but deal with. Making the dance is one way to deal with our concern.”13 In other words, adagio activism is a decelerated, durational process compelled by a deeper searching, a patient and corporeal discernment that reveals matters of great importance. Eiko & Koma’s body of work is evidence that the themes of their dances are not random but are ones with which they deeply connect, with the result that those things they choose to explore, they explore exhaustively. Moreover, their dances do not signify these matters of importance but realize them.14 That is, dance for Eiko & Koma is not only a way to come to understand something, but a means to give it physical form, to actualize it in the world.

Slowness for Žižek, and for Eiko & Koma, is therefore not a benign aesthetic but a political intervention, like a labor slowdown when workers intentionally decrease production on an assembly line to demonstrate their centrality to the success of capitalism.15 Slowing down enables analysis of a complicated and bewildering situation, like the function of violence, which Žižek categorizes as subjective and objective. Subjective violence includes acts committed by an individual or group of individuals that visibly disturb the status quo; crime and terror are two obvious examples. Objective violence, on the other hand, is the necessarily invisible violence—both symbolic and systemic—that sustains the very status quo from which subjective violence so graphically stands out. The urgency (Žižek calls this a “fake urgency”) with which we are prompted to respond to subjective violence actually serves to mask objective violence and prevents us from comprehending how objective violence in fact begets subjective violence. Ultimately, for Žižek the most profound act is one “that violently disturbs the basic parameters of social life.”16 It is at its heart “a radical upheaval of the basic social relations”17 that could disturb the functioning of objective violence.

Eiko & Koma’s dances over the past four decades—generating connections and change over time and across borders—offer an alternative model for how art can reflect and transform society. Avant-garde art need not only cause radical breaks; it can also effectively engage in a slow, sustained process of change. Slowness as choreographic method provides the time to learn how to develop alternative ways of working in the world, including tactics that may allow one to pass outside the visibility of subjective violence, reveal the functioning of objective violence, and create alliances that could prove effective in countering objective violence. Eiko & Koma say they make work about something they need to discover, not something they already know. Their concerns, the things that they “cannot help but deal with,” require repeated and careful analysis, which they conduct through their choreography.

In both Eiko & Koma’s body of work and in this book, slowness is foundational without itself being the point of the dance or the analysis. It is a consistently used tool, but its results are not always the same. For example, Eiko & Koma use slowness in their dances for different ends: it may be a way to prolong mourning or to facilitate connections among humans, nature, and technology. Slowness can also draw attention to cycles of destruction and regeneration, making the long duration of cycles over lifetimes comprehensible over the course of one dance. Similarly, slowness in this book provides the foundation for viewing Eiko & Koma’s work; it is a prerequisite that must be understood before the analysis can proceed. As such, aesthetics as politics is not the focus of this book, but it is the foundation. The focus instead is on the variety of ways that Eiko & Koma employ their aesthetics and to what end.

Asian/American/Dance

When I was doing research in Japan, people would say to me, “Well you know, Eiko & Koma are really American.” They are simply not considered part of Japanese dance history, even though they began performing while briefly living at Hijikata’s Asbestos Hall and studied with Ohno early in their careers. This view is understandable given that the dancers have had their primary residence in New York since 1977 and—not counting their experimental performances in the early 1970s—have only performed in Japan a handful of times. On the other hand, Eiko & Koma’s significance in American dance history and their ongoing role in American concert dance is often elided by a popular discourse that persistently categorizes them as Asian. Rather than pointing to specific political, historical, or cultural markers that might be relevant to Eiko & Koma’s work, “Asian” too often slips into an Orientalism that says far more about Asian American racialization and the legal and discursive regulation of Asian bodies in the United States than it does about the dance at hand. Moreover, these perspectives that would have the dancers be either generically American or Asian foreclose consideration of the complex personal, political, and dance historical webs that form the foundation of the work.

In this book I situate Eiko & Koma both as Japanese artists who began performing through their encounters with butoh but who have never called their work by that name, and as Asian American artists in American concert dance who have had international success. This orientation to their choreography has theoretical and methodological implications that require me to cross boundaries of dance studies, Japanese studies, and Asian American studies, and take into account theories of transnationalism, diaspora, and Asian American racial formation. In the process, I seek to expand critical understanding of the radical nature of Eiko & Koma’s body of work, while also demonstrating how that work—of which the artists themselves sometimes question whether it is indeed dance or choreography—influences the field of dance studies. The book contributes to the nascent body of literature concerned with Asian American dance and expands American dance history to include the contributions of Asians and Asian Americans.

By insisting on thinking about Eiko & Koma as part of American dance history, I join Asian American scholars who examine the ways Asians have or have not been included in the idea—and state—of America. This thinking is reflected in the book’s subtitle, Eiko & Koma’s Asian/American Choreographies. I follow David Palumbo-Liu’s use of the solidus to signal a simultaneous connection and separation, inclusion and exclusion, between Asian and American.18 The addition of the slash points to the repeated exclusions of Asians from America, beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1872, even as the punctuation simultaneously resists the nationalist project of the subsumption of Asians into America, particularly as model minorities after the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. The slash furthermore highlights the unsettled state of both terms, acknowledging repeated and historically changing international as well as intranational contact. This is a particularly appropriate approach for Eiko & Koma, who have been permanent residents of the United States since 1979 and whose career is inextricable from American concert dance, but who maintain their Japanese citizenship.

Unlike Asian American theater and performance, Asian American dance remains woefully undertheorized.19 Dance studies is itself a relatively new discipline, and while an analysis of race, class, and gender has been central to its formation, Asian American choreographers and dancers have remained largely invisible. I lean heavily on the work of Yutian Wong, a scholar at the forefront of Asian American dance. She is joined by scholars such as Priya Srinivasan and SanSan Kwan in developing a nascent body of literature on Asians dancing in America, the meaning of dance in diasporic communities, and the contribution of Asian Americans to American dance history.20 As Wong established in the essay “Towards a New Asian American Dance Theory: Locating the Dancing Asian American Body” and expanded on in her book Choreographing Asian America, Asian American contributions have been largely erased from American dance history, despite the fact that, as she asserts, “American modern and postmodern dance forms are always already Asian American.”21 Her argument is strongly influenced by Brenda Dixon Gottschild’s efforts to expose the ways that African American culture, via the presence of Africanist movement qualities, infuses American dance to the point that American dance is African American.22 Wong persuasively demonstrates that Asian American bodies form an invisible foundation of American modern and postmodern dance. For example, modern dance “pioneer” Ruth St. Denis based many of her early twentieth-century Orientalist dances on work by Nautch dancers from India she met in New York, sometimes even using their bodies onstage as backdrops to her solos.23 Merce Cunningham famously began employing the I Ching in the 1950s in his chance operations, which separated dance making from narrative and even the express intent of the choreographer. Steve Paxton later drew heavily from aikido, among other movement forms, in his development of contact improvisation in the early 1970s. In each of these cases, the unacknowledged appropriation of Asian bodies and concepts is regarded as the product of individual (white, American) genius.

It is not a matter, however, of simply inserting “forgotten” dancers back into the dance history canon. As Wong deftly demonstrates with the case of Michio Ito, a Japanese dancer who enjoyed enormous success in the United States before being deported to Japan during World War II, repeated revivals and retrospectives of his work have never quite remedied his absence from the canon.24 An examination of American legal, political, and popular discourses reveals that the pattern in dance history of alternately emphasizing or erasing Asian Americans is in fact a fundamental condition of American national identity formation. Karen Shimakawa explicates this condition as a process of abjection—à la Julia Kristeva—in which Asian Americans are both “constituent element and radical other”25 of the nation. In other words, “America” is defined through the (ongoing) exclusion of Asian (American)s, who nonetheless constitute an essential part of that same identity. It is important to note that the abject is always internal to the deject, even as it is excluded. This ambiguity or contradiction is reflected in the literal, material, legal, and symbolic abjection of Asian Americans. For example, Japanese internment excluded Japanese Americans from “America” by drawing them further in. Another example is the alternation between legal exclusion and model minority status. Abjection is, after all, an unstable process, requiring continuous reinforcement.

Asian American studies has proven invaluable for teasing out the complex forces that impact Asian American dancers in general and Eiko & Koma in particular. This book asserts that what Eiko & Koma do onstage—their choreographic decisions—can be productively analyzed as Asian American cultural critique. In addition to guiding my orientation to the dancers’ body of work as a whole, the discipline is also a source of scholarship on mourning, melancholia, reparation, intercultural performance, and multiculturalism that helps me analyze Eiko & Koma’s predominant themes. However, I must acknowledge that the discipline’s focus on art as a source of legible stories of immigration, oppression, and resistance has meant that text-based productions like literature and theater have been favored, while body-based or abstract work runs the risk of not being visible as Asian American. This is not unique to Eiko & Koma, but is a larger issue faced by many Asian American performers. Wong discusses the same phenomenon in relation to work by Sue Li-Jue and Denise Uyehara, noting that pieces lacking an explicit Asian American critique become “unidentifiable in terms of inhabiting a thematic Asian American niche.”26 In other words, content rather than form is where politics becomes comprehensible within the field.

This book takes as a given that choreography is inherently political, that aesthetic choices reflect political investments, and that dancing bodies are formed within regimes of discipline and viewed by their audiences in the context of the politics of representation. Though these statements may seem self-evident, this kind of thinking about dance only became possible with the rise of dance studies scholarship beginning in the mid-1980s and has not fully made its way into other disciplines.27 In bringing together dance and Asian American studies I, like Wong, seek to racialize and politicize aesthetics. In particular, I aim to demonstrate how the US Orientalism inherent in American modern dance has obscured the politics of Eiko & Koma’s dances, even while awarding those dances the highest honors. At the same time, I argue for the choreography itself as Asian American critique; in doing so, I assert that dance is not merely a vehicle for telling stories, but more important, is a way of enacting a particular politics.

Methodology

My goal to elucidate the politics of Eiko & Koma’s choreography is best achieved through choreographic analysis, through which I critically unpack the dances to demonstrate what these unique works effect in the world. My primary sources, then, are the dances themselves. I draw on extensive observation of Eiko & Koma’s performances, rehearsals, and workshops. Live performances I was not able to see in person I watched through video documentation and studied through photographs, promotional materials, newspaper previews and reviews, and program notes available in Eiko & Koma’s personal archives and in collections at The Jerome Robbins Dance Division of The New York Public Library and the San Francisco Museum of Performance + Design. Media dances created specifically for film or video I have watched on my computer, on gallery walls, and in university and museum screening rooms.

Eiko & Koma’s dances challenge an easy separation between choreography and performance. Because they are both choreographers and usually the only performers of their dances, it can be difficult to separate Eiko & Koma’s movement style and choreography from their individual bodies. Furthermore, the vocabulary often appears deceptively simple: small, subtle, continuous movements that contain none of the virtuosity or proscenium-oriented, presentational qualities of many other dance forms. Nonetheless it is possible to construct a choreographic analysis based on the following questions: What choices have the choreographers made in the creation of each piece, including the title? What is the site of the dance? How do the bodies move through time and space? What is the quality of their movement? Where are they in space? Are there other bodies in addition to Eiko & Koma? What is the relationship between the bodies onstage? How do the costumes, music, and sets relate to the moving bodies? What meanings accrete to this series of decisions? The writing of Thomas DeFrantz in Dancing Revelations is a particular influence in this sense.28 His richly descriptive prose paints a detailed picture of each dance, including movement vocabulary and quality, music, structure, and spacing. In each paragraph DeFrantz shows his readers what is happening in the dance and then, based on the evidence he presents, tells them what the choreography means; his analysis of many of Alvin Ailey’s eighty works forms his arguments, rather than merely supporting them. DeFrantz’s specific and evocative writing style employs the very same Africanist aesthetics that he detects in Ailey’s choreography, which pushes me to elaborate the aesthetic principles that undergird Eiko & Koma’s movement vocabulary, such as slowness.

Even as I foreground the process of choreographic analysis, I must acknowledge that my analysis could not have developed without an embodied perspective based on my experiences studying with Eiko & Koma, whom I first met in 2006 when I was a graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles. Indeed, Susan Leigh Foster asserts in Reading Dancing: Bodies and Subjects in Contemporary American Dance—arguably the first text to outline choreographic analysis as a methodology—that developing a visual, aural, and kinesthetic knowledge of movement is a prerequisite to discerning a dance’s codes and conventions.29 In addition to taking Eiko & Koma’s movement class, Making Dance as an Offering, I also worked with Eiko to produce a written record of that class and served as an unofficial teaching assistant for her undergraduate seminar, Delicious Movement for Forgetting, Remembering, and Uncovering. Although I had seen one or two of their dances prior to meeting them, it was only through dancing with them twice a week, seeing how they contextualized their work with other artists and thinkers, and talking to them in their temporary office that I came to appreciate the full force of the choreography. At the same time I began to notice how Eiko & Koma’s dances were frequently misread as foreign and mystical: a type of meditation, or something akin to the process of tending a Zen Buddhist rock garden. I puzzled over the lack of critical and scholarly writing about their significant body of work that dared probe beneath the slow-moving surface. Why were their acclaim and success, both richly deserved, accompanied by such a superficial consideration of their choreography rather than a deep engagement with what the movement was actually doing? Through my experience working closely with Eiko & Koma, I became compelled to develop the kind of analysis I felt was lacking. As the daughter of a Filipino American father, I have a personal stake in challenging the way Asian bodies in the United States are rewarded as exceptional but at the same time are never quite allowed to be “American.”

Although this book is not an ethnography of Eiko & Koma, I did employ the ethnographic method of participant observation to continuously deepen my knowledge of the movement I analyze. Since 2006 I have spent many hours with Eiko and Koma at their home in New York City and have traveled to their performances, workshops, exhibitions, and residencies across the United States and in Japan and Taiwan. I have also participated to varying degrees in their work. For example, in addition to participating in numerous Delicious Movement workshops, I have done a range of tasks, including stage managing performances, mending props, assisting backstage, handing out programs, and more. In 2012 I worked as a Mellon Archive Fellow with the Dance Heritage Coalition to inventory, assess, and organize Eiko & Koma’s personal archives, alongside Eiko and Patsy Gay, a specialist in archival methods. I also worked with Eiko to help her conceptualize their Archive Project, consistent with their artistic vision and practices. This hands-on approach to research has given me enormous insight into individual choreographic projects as well as the entire span of Eiko & Koma’s career.

In addition to analyzing Eiko & Koma’s choreography, it is important to pay close attention to how Eiko and Koma’s early years in Japan, their time performing in Western Europe, and their decision to settle in New York influenced both their movement style and concerns. This contextual information is not always available from the dances themselves and must be acquired through supplemental historical and archival research and interviews with people who were there and can give firsthand reports. I have interviewed Eiko & Koma numerous times in addition to spending hours simply hanging out and chatting. My relationship with the artists has given me access to their longtime friends, collaborators, presenters, and critics, who have generously shared their thoughts, memories, and materials with me through formal interviews and casual conversations. These interviews provide vital background information and form part of the evidence to support my argument about Eiko & Koma’s choreography.

I furthermore examine archival materials about Eiko & Koma to ascertain the extent to which changing discourses of race, multiculturalism, and identity in the United States have impacted how their choreography is viewed. How was contemporary Japanese performance received in the mid-1970s in the wake of the Vietnam War and in the midst of a nascent Asian American political movement? What does it mean that butoh performances by Kazuo Ohno and Dairakudakan proliferated alongside performances by New York–based Japanese artists Eiko & Koma and Kei Takei at precisely the moment that the Japanese American redress movement, which sought reparations and an official government apology for the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, gained traction in the 1980s? How have Eiko & Koma benefited from multicultural policies and practices of the 1990s? Have those same multicultural policies and practices also obscured the force of Eiko & Koma’s dances? Furthermore, what does it mean during this time period to be performing “modern” Japan in the form of an avant-garde movement practice and yet to be read in Orientalist terms, which generally tie the “Orient” to traditions fixed firmly in the past?

Some of the same questions I ask of the archive can also be asked of Eiko & Koma, presenters, dance critics, and the dancers’ artistic collaborators through interviews. For example, Beate Sirota Gordon, the former performing arts director of the Japan Society and the Asia Society and the first presenter of Eiko & Koma’s work in the United States in 1976, has provided me with invaluable information about the cultural contexts in which Eiko & Koma began to perform in the United States.30 At that time, Gordon’s programming decisions in New York City played a large role in determining what “Japanese” meant in America, as artists she booked for shows at the Japan Society often subsequently toured all across the country. Similarly, presenters such as Charles Reinhart of the American Dance Festival and Jeremy Alliger of the now defunct Boston-based Dance Umbrella played a large role in defining Eiko & Koma’s work through the contexts in which their dances appeared, establishing the choreography (often commissioned as well as presented by these agencies) as American in the former case and as part of a cutting-edge Japanese dance community in the latter. These brief examples are illustrative of the ways presenters, critics, and collaborators have participated in the construction of Eiko & Koma’s work before it is choreographed, as it is performed, and after the performance is over. Conducting interviews allowed me to get the details and nuances of this information, often not available in archives and not evident in the dances themselves.

The result, I hope, is that my engagement with Eiko & Koma and their choreography mirrors their own engagement with their work. Like them, I do not want to approach their work “with a concept that is just hunted,” but I want the analysis to develop out of a sustained engagement with the dances themselves. My goal is to employ their choreographic method in my analysis in order to offer readers a more complex and slowed-down experience of Eiko & Koma and their work. Taken together, these varied experiences, along with analytical, archival, and ethnographic methods, suggest the major themes, or concerns, of Eiko & Koma’s body of work.

Overview of Chapters

Flowers Cracking Concrete places Eiko & Koma’s dances in their political, dance historical, and cultural contexts and analyzes those dances for their individual and collective impact. The first two chapters pay particular attention to establishing Eiko & Koma’s influences and early history in order to intervene in the Orientalist discourse that too often defines them as singular and timeless. It is true that their work is unique, but it developed through particular life and artistic decisions and encounters, not through some inherent cultural or national essence. The examination of Eiko & Koma’s early career in chapters 1 and 2, for example, provides an alternative view of three crucially important periods of dance history, but from the perspective of marginal participants in these moments. What was it like to study with the key figures of butoh for short periods of time in the early 1970s, but not be in the inner circle of disciples who worked with Hijikata and Ohno for years to develop their unique butoh expressions? What did it mean to study dance in Germany with Chmiel at a time when her Wigman-influenced style was out of favor, but Tanz Theater had yet to predominate? How was it possible to be integrated into the New York downtown dance scene as newcomers to the United States whose performance style differed from the predominant white abstract and pedestrian postmodern dance? And how did each of these encounters shape Eiko & Koma’s body of work?

Chapter 1, “From Utter Darkness to White Dance,” traces the development of Eiko & Koma’s political commitments, aesthetics, and dance style from their time growing up in postwar Japan through their early “cabaret” performances in Japan and their initial dances in Europe and the United States. The chapter focuses particularly on the years 1971 to 1976, during which the pair moved from the “utter darkness” of not only their ankoku butoh teachers but also the political situation in Japan to the premiere in New York of what they call their first piece of set choreography, White Dance (1976). I argue that for Eiko & Koma choices about how, where, and at what pace to move have from the beginning always been both choreographic and political decisions.

After their American debut, Eiko & Koma returned briefly to Japan before moving to the United States permanently in 1977, where they immersed themselves in the New York downtown dance scene, creating one new piece each year and establishing themselves as critically acclaimed mainstays of American avant-garde dance. Chapter 2, “‘Good Things Under 14th Street’,” considers Eiko & Koma’s experimental choreography—Fur Seal (1977), Before the Cock Crows (1978), Fluttering Black (1979), Trilogy (1979–1981), and Nurse’s Song (1981)—in relationship with their new home in New York City, placing the duo’s work in the larger contexts of American postmodern dance, the downtown dance scene, and 1970s politics. From this point on, I claim, Eiko & Koma’s work was deeply engaged with participating in and responding to American—and particularly New York City—influences. My analysis of these early dances shows that despite a sometimes radical change in style from piece to piece, Eiko & Koma demonstrate a consistent commitment to choreographing oppositional politics. This consistency notwithstanding, I suggest the dances that were most successful with critics were those that employed slowness as a choreographic method.

Chapter 3, “Japanese/American,” shifts the perspective from the contexts in which Eiko & Koma began to make dances to the discursive contexts that impacted the reception of their work. Specifically, the chapter examines a change that took place between the early 1980s and the mid-1990s in how Eiko & Koma’s work was represented and understood by producers and critics. At precisely the time when Eiko & Koma’s work was becoming more integrated into American dance, the pair—initially called “avant-garde” and “postmodern”—became increasingly presented as “Japanese” and “Asian,” particularly after Japanese butoh companies began to appear on American stages in the early 1980s. Through an analysis of dance reviews in the New York Times and other New York papers covering dance, I argue that Eiko & Koma have not been legible to US audiences as Asian American, or even American, because discourses that interpellate them as Japanese or Asian have been too dominant. I discuss multiple discourses that impact Eiko & Koma’s work, including what Barbara Thornbury has called a “kabuki discourse,” something I have identified as a nuclear discourse that is particularly entwined with the American reception of butoh, and an Asian American discourse.

Having discussed in chapters 1 through 3 the cultural, dance historical, and discursive contexts of Eiko & Koma’s early work, in chapters 4 through 7 I abandon chronology in favor of analyzing recurrent choreographic and kinesthetic themes evident in dances from across Eiko & Koma’s body of work, including nature, mourning, and intercultural alliances. These chapters individually and as a whole demonstrate how the duo’s artistic concerns cycle throughout their repertoire, extending over long periods of time and sometimes overlapping with other themes. Just as Eiko & Koma’s choreography and career constantly return to earlier projects to mine them for further significance, my analysis, too, cycles through temporalities to get at what the dance is about and what it does. Individual works cannot be discussed in isolation, but must be understood in relation to other dances that grapple with the same ideas or produce the same effects. For example, when analyzing a particular cycle within Eiko & Koma’s body of work, I focus first on one dance in particular, then compare and contrast that dance with others that precede and follow it in order to articulate what remains constant over the decades and what changes, to what effect. Moreover, these cycles do not necessarily take place in a defined span of time and then give way to another theme. Rather, Eiko & Koma may return to an earlier concern years later. Chapters 4 through 7 thus overlap in terms of chronology. Furthermore, no one theoretical approach could account for all of the cycles. Each theme calls for its own unique frame of analysis.

Chapter 4, “Dancing-with Site and Screen,” explores the prominence of human-nature relationships in Eiko & Koma’s body of work, as exemplified in River (1995) and as seen in stage pieces like Grain (1983) and Night Tide (1984), site dances like The Caravan Project (1999), screen dances such as Husk (1987), and the living installation Breath (1998). Specifically, I home in on the relationships choreographed in these pieces between nature and culture, bodies and technology, that are not based in binaries or mutual exclusion but in interconnection, or what I call interface. I argue that Eiko & Koma practice in these dances a choreographic methodology of “dancing-with” nature and technology that enables the generation of interfaces through a slow and concerted process in which all active participants, including potentially the audience, are altered. This body of work is a recurring reminder of the potential for creating alternate ways of being in the world, in which the relationship between nature and technology has many complex possibilities beyond an either/or binary.

Chapter 5, “Sustained Mourning,” examines Eiko & Koma’s decades-long investigation of mourning as a choreographic practice. Here slowness refers not only to the movement in a particular dance, but also to Eiko & Koma’s long-term focus. In works including Elegy (1984), Lament (1985), Wind (1993), Duet (2003), and Mourning (2009), the duo prolongs mourning such that it acts as a stubborn, even resistive melancholia. I draw on psychoanalysis, Asian American studies, and art analysis to provide a context for my theorization of the labor of Eiko & Koma’s prolonged mourning and its effects. I argue that this group of dances theorizes mourning as not merely a private, individual process, but a societal, public melancholia that highlights issues and events that can never be resolved but must nonetheless be grappled with. Their choreography, I suggest, accomplishes this with performances of a sustained mourning through which Eiko & Koma evidence the ability to dwell in a space of heightened emotion without necessarily effecting a transformation of those strong feelings, both over the course of one dance and throughout the decades of their work. Grief in this case becomes a physical labor—sometimes even a battle—on endless repeat. This corporeal theorization of mourning is a crucial reworking of the concept that rejects the beginning-middle-end ideology of Freudian psychology in favor of a postwar temporality in which such a linear resolution is no longer possible.

Chapter 6, “Ground Zeroes,” demonstrates how Eiko & Koma’s post-9/11 dance, Offering (2002), drew on their long-term engagement with sustained mourning. Together with other dances, including Event Fission (1980), Land (1991), Raven (2010), and Fragile (2012), Offering calls attention across time and continents to a shared history in Trinity, New Mexico, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and New York City. I argue that this collection of Eiko & Koma’s dances generates a critical transtemporal and transnational space in which divisions between here and there, now and then, us and them are called into question. I further suggest that these pieces differ from the melancholic choreography of the previous chapter, in that they transform rather than sustain mourning. These dances display a process of metamorphosis that occurs over the course of a piece, in which the bodies become something new through interacting with the other elements in the piece. I understand this transformation of mourning through the notion of reparation, a concept derived from psychoanalysis and adapted by Asian American studies scholars, that offers the possibility of creative action to productively address crisis and loss.

Chapter 7, “‘Take Me to Your Heart’: Intercultural Alliances,” centers on a group of dances beginning with Cambodian Stories (2006) that points to an important attention to intercultural alliances in Eiko & Koma’s work. Made in collaboration with young painters from the Reyum Art School in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, these intergenerational and interdisciplinary works among Asians and Asian Americans—including Cambodian Stories Revisited (2007), Quartet (2007), the revival of Grain (1983/2007), and Hunger (2008)—were presaged by the duo’s collaboration with Anna Halprin in Be With (2000). In particular, this chapter engages with the history of intercultural performance to demonstrate how Eiko & Koma’s work, focused on what I call choreographing intercultural alliances, differs from other noted intercultural collaborations that often remain mired in Orientalist discourses or uneven power structures. Unlike the interfaces of chapter 4, intercultural alliances do not attempt to create a new entity, but instead seek to enact strategic ways of working together, undoing in the process assumptions that separate East and West, modernity and tradition.

The concluding chapter, “In Lieu of a Conclusion: ‘Step Back and Forward, and Be There’”31 takes a long view of Eiko & Koma’s body of work through the lens of their Retrospective Project (2009–2012) and ongoing Archive Project. I discuss the live installation Naked (2010) as an emblematic work of the Retrospective and Archive Projects that explicitly engages Eiko & Koma’s core choreographic practices of site-adaptivity and (re)cycling, which extend their concerns across time and space. In this way I demonstrate that Eiko & Koma’s archival practices are in fact a continuation of their choreography. I then review current debates about performance archives in order to highlight Eiko & Koma’s intervention in the understanding of what it means to archive. I argue that Eiko & Koma’s ongoing engagement with their own choreography—in the form of continually revisiting ideas and recycling movement, costumes, and sets—challenges the future-orientation of archives and interrupts the body-documents binary that has developed between those favoring the body as an archival site and those advocating for the document-as-performance. In contrast, Eiko & Koma’s site-adaptive and cyclic choreographic practices show that archiving is an ongoing activity that generates connections among bodies, objects, and sites.