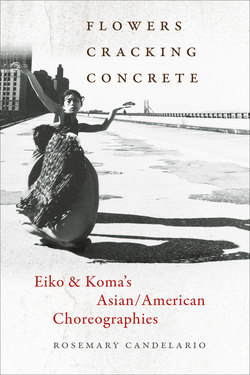

Читать книгу Flowers Cracking Concrete - Rosemary Candelario - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

FROM UTTER DARKNESS TO WHITE DANCE

Eiko & Koma had their New York premiere with White Dance at Japan Society’s Japan House on May 6, 1976. The delicate yet tension-suffused dance featured periods of extended stillness punctuated by moments of absurdity: a slap, a cry, a cascade of potatoes. Although only a one-night engagement, the performance enabled a six-month sojourn in the United States, including subsequent performances at The Cubiculo, The Performing Garage assisted by Dance Theater Workshop, and the New York Public Library at Lincoln Center (the latter under the title The White Moth). Prominent dance critics at The Village Voice, Dance Magazine, and Soho News called the work “shocking in some way I can’t articulate”1 and “profoundly exciting,”2 in part for the way it “coheres and engages our interest because we watch Eiko and Komo [sic] repeatedly enter, inhabit, and leave the inextricably linked states of fragility and determination.”3 How is it that two Japanese student activists turned dancers were able to create such a stir in New York, both uptown at the venerable Japan Society and NYPL and downtown at venues known for producing avant-garde and postmodern performance? Where did this dance come from? What was it about their dance that left dance critics unable to articulate meaning yet captivated nonetheless?

This chapter examines the development of Eiko & Koma’s political and aesthetic commitments during their early years in Japan and their initial forays into dance performance in Japan, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United States. I contend that their choreography evidences from the very beginning an oppositional stance that although devoid of explicit activist messages nonetheless proposes ways of being in the world that challenge structures of power. It is also during this time that Eiko & Koma can be observed making decisions about what is important to them and how to incorporate it into their dancing. As Eiko said in a 1988 interview, “The question is: How shall I continue? What do I preserve and what do I not take in? What do I fight against in consideration of keeping something that I care about?”4 I open with an introduction to Eiko and Koma’s background growing up in postwar Japan and coming-of-age as activists in late 1960s and early 1970s Tokyo.5 The focus then turns to their formation as dancers and dance makers from 1971 to 1976, first in Japan with the key figures of butoh, Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno, then through more than two years of performance and study in Europe, including with Mary Wigman dancer Manja Chmiel, and ending with their first performances in the United States. This period of movement from one continent to another parallels the pair’s movement away from the “utter darkness” of their ankoku butoh teachers toward their own White Dance. At the same time, their trajectory provides the opportunity to retrace some of the paths of twentieth-century modern dance history.

The Dance of Utter Darkness

In a time line Eiko & Koma created for their Retrospective Project, the dancers constructed a chronological representation of their lives and career.6 With this document, the pair situated their body of work historically, culturally, and politically, including not only notable moments from their career, but also significant events such as the Beatles’ first concert in Tokyo, the beginning of the Vietnam War, and their own participation in Jimmy Carter’s 1980 presidential campaign. Notably, the time line begins not with Koma’s birth in provincial Niigata on Japan’s northwestern coast in 1948 and Eiko’s in Tokyo in 1952, but with the defeat of Japan in 1945. By marking their own beginnings with this decisive ending, an act of aggression and destruction unparalleled in human history, they acknowledge this moment as a major rupture, a turning point after which nothing can be the same. With this deliberate staging of their relationship to history, Eiko & Koma demonstrate how their sense of time extends beyond what we normally think of as beginnings and endings, a quality that has become characteristic of the sense of time in their work. The time line also places the dancers’ births in the context of the end of the US occupation of Japan and the duration of the Korean War, and therefore subject to and implicated in geopolitical entities and events well beyond the local.

Though this act of staging their relationship to history is a recent one, there is no doubt that aftershocks of war and occupation resonated in both of their lives. Eiko and Koma were small children during the period of reconstruction after the intense destruction of World War II. Hiroshima and Nagasaki of course were devastated by the atomic bombings, but many other cities, including Tokyo, were firebombed and had to be rebuilt. Evidence of the war lingered, through broken infrastructure, the visible evidence of wounded war veterans, and US military occupation. Even after occupation officially ended in 1952, US military bases in Japan served as supply stations for the Korean War and later for the war in Vietnam, keeping armed conflict in the forefront of people’s minds, even as Korean residents of Japan were relocated to North and South Korea.

Takashi Koma Yamada’s parents split up when he was still small.7 His father, reportedly haunted by the war, took Koma’s brother, while Koma remained with his mother. Their life together in the often snow-covered port city of Niigata was modest. Koma talked in a movement workshop about how his mother would split an egg with him during his childhood, giving him the yolk to eat with his rice, taking only the white for herself.8 In contrast, Eiko Otake was the only child of a banker and homemaker. Though based in Tokyo, her family spent a number of years living in Tochigi Prefecture in rural central Japan for her father’s job, which gave Eiko an early appreciation for nature. In the midst of this solid middle-class foundation, arts and politics were also strong currents in the Otake household. Both of Eiko’s grandmothers were geishas (indeed, Eiko has worn one of her grandmother’s silk kimonos as a costume for years), and her grandfather was an artist. And despite her father’s profession, he was also a communist.9 In this politically active and creative environment, Eiko took three years of modern dance classes as a child and played the piano, but reportedly did not have an affinity for either.

The mid-1950s through the early 1970s in Japan was a time of intense change, including rapid industrialization and urbanization coupled with enormous economic growth. These developments were not disconnected from postwar US involvement in the country, a relationship concentrated in (but not limited to) the US-Japan Mutual Cooperation and Security Treaty, referred to in Japan as “Anpo.” The treaty came up for renewal in 1960 and 1970 and in both cases was driven through by the ruling party and riot police, despite massive protests against it. In the wake of the treaty’s renewal, the government promoted what William Marotti calls “a depoliticized everyday world of high growth and consumption and a dehistoricized national image”10 in order to defuse the opposition. By the time of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, this strategy appeared to be successful. All evidence of postwar destruction was gone, and in its place was a modern, regulated, thriving version of Japan for the world to see.

In the midst of such radical changes, many Japanese struggled with how to negotiate and express their relationship to those changes. As Marotti eloquently states, “Artists in Japan discovered hidden forms of domination in the everyday world and imagined ways in which their own practices might reveal, or even transform, such systems at their point of articulation in people’s daily existence.”11 In other words, even as structural and societal changes were implemented, a vibrant avant-garde was on the rise, eager to develop and implement contestatory and interventionist practices that could impact the new status quo, both during the Anpo protests and in the deflated aftermath of the security treaty’s passage. The Neo Dada Organizers, for example, were a group of nine artists including Genpei Akasegawa, Ushio Shinohara, and Masunobu Yoshimura who came together for anti-Anpo protests and a series of three exhibitions in 1960. In both protest and art (or more precisely, anti-art), they favored physical and sometimes violent action with everyday objects and rubbish: throwing stones at the Diet, slashing canvases, karate chopping chairs. Akasegawa then went on to found Hi Red Center (Hai Reddo Senta, active 1962–1964) with Natsuyuki Nakanishi and Jirō Takamatsu. That group created public events that commented on and critiqued the sanitizing of Tokyo even as they conspicuously participated in it. Their event, HRC shutoken seisō seiri sokushin undo ni sanka shiyō! (Let’s participate in the HRC campaign to promote cleanup and orderliness of the metropolitan area!, 1964), featured Hi Red Center members in white lab coats and surgical masks sweeping and scrubbing sidewalks in the Ginza neighborhood of Tokyo shortly before international attendees of the Olympic games arrived. These artists took the changes in society, politics, and the city and performed them to their extreme and absurd, if logical, conclusions.12

Not all artists of the avant-garde were interested in direct action, however. In the midst of pervasive anxiety about urbanization and industrialization, there were also frequent attempts to reconnect to or re-create tradition. This instinct sprang at least partially from the reality of rural to urban migration and the sense that rural traditions were being lost. The reach for tradition was, however, more connected to a modernist interest in indigenous art, rather than a form with which rural folks would have identified. In this case, rather than being an opportunity for an encounter with the strange and foreign, as with European surrealism, the turn was to Japan’s own indigenous and folk practices. For many Japanese artists, including architect Kenzō Tange, visual artist Tarō Okamoto, and designer Kiyoshi Awazu, this was evident through their turn to the prehistoric Jōmon period for figurative and conceptual inspiration. This served two ends. First, as Michio Hayashi so elegantly put it: “The primitive cultural force is summoned as the dialectical other vis-à-vis modern technology.”13 Second, the turn to the indigenous and the folk gestured to a people unsullied by the consequences of the nationalist-modernist ideology that drove the state for almost a century. The idea of a prenational Japan provided an alternative model to both Japanese empire and industrialization in the midst of midcentury upheaval and restructuring.14

Eiko and Koma, like many young people in Japan, confronted the fundamental changes in society by joining the vibrant student protest movement that swept Japan, and much of the world, in the 1960s. Although aware of the dynamic spirit of avant-garde experimentation, Eiko says, “We were too busy with anti-government and anti-Vietnam War demonstrations to pursue art seriously.”15 Koma joined the movement when he arrived in Tokyo as a political science student at Waseda University in 1967. Eiko, following her family’s example, had been involved in activism from an early age and even led the first strike by Japanese high school students in 1969. When she entered the law department at Chuo University in 1970, her activism continued.

The 1960s Japanese student movement had its roots in the postwar years. The 1947 Constitution, though drafted by an American team led by General Douglas MacArthur, concentrated Japanese optimism about liberal changes in Japanese society, including individual rights, a democratic government, and a commitment to international peace.16 Many people, however, felt betrayed by the Japanese government’s military relationship with the United States as concentrated in Anpo, which they felt contradicted Article 9’s renunciation of war.17 By 1968, the resurgent New Left student protest movement had expanded its concerns to include Vietnam, Okinawa (which remained under US control until 1972), and the very nature of universities and education. Noting the relationship between the Japanese government and higher education, students resisted indoctrination into state ideology, which they linked to capitalism and militarism. The groups Zengakuren (the All Japan Federation of Students’ Autonomous Bodies, founded in 1948) and Zenkyoto (Joint Struggle Committee, 1968–1970) were at the center of this unrest, a mass movement employing direct action, riots, strikes, and occupations. By the early 1970s a lack of effective unity at the time of the 1970 renegotiation of Anpo as well as police suppression and violence led to splintering of the movement into factions. Finally, the public and bloody United Red Army fiasco in 1972, in which a revolutionary armed group killed some of its own members and engaged in a drawn-out standoff with police, signaled the end of the student movement.

In 1971 both Eiko and Koma had begun to feel the effects of the dogmatic and increasingly violent student movement, and they began to seek other outlets for their oppositional beliefs. Eiko explains the transition in this way:

While numerous political theorists—none standing out any more than the others—presented us with logic, idealism, and tactical thinking, somehow these things led us to despair. By contrast, [artists such as filmmaker Oshima Nagisa, playwright/theater director Kara Juro, artist Kudo Tetsumi, and designer/artist Yokoo Tadanori, as well as European filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and Federico Fellini] showed us how they built their lives upon their confusion and frustration. In their works, we sensed that the means and the end are inseparable, that being revolutionary means being radical, and that the body is our vessel and foundation for exploration, experimentation, and expression.18

For Eiko and Koma, then, the move from the barricades to the dance studio was not about abandoning their political ideals but about finding a new, sustainable way to practice them.

Given the close associations between art and protest in 1960s Japan, Eiko and Koma’s transition from one movement to the other is not so unusual. Marotti notes that members of the new avant-garde made “an attempt to conduct politics directly out of artistic performance, neither as an adjunct to protest nor through the conventional forms of agitprop but rather through the political potential of their practice itself.”19 Though the methods of protest were different, the goals were often aligned. For example, the policy statement of the 1969 conference of the student body of Waseda University declared: “We start from individuals … There should exist neither sectarian nor bureaucratic logic. We must start speaking with ‘words’ from inside of ourselves…. Let us found a radical struggle based on self-reliance and individualistic conceptions.”20 This call for individual determination as opposed to dependence on institutions or ideology echoed the turn to personal, immediate experience already present in the new avant-garde, particularly through performance, installation, and even painting that evidences the involvement of an active body. These practices were especially evident in the Gutai Art Association, including Kazuo Shiraga’s Challenging Mud performance (1955) and his method of painting with his feet; Shōzō Shiramoto’s paintings made by hurling glass bottles full of paint; and Saburō Murakami’s Passing Through (1956), in which he propelled himself through twenty-one paper screens.21

For Koma, leaving the student protest movement and New Left politics meant leaving behind the entrenched hierarchies and leader-follower roles of the old society.22 For both Eiko and Koma, withdrawing from the student movement was about opposition to dogmatism and violence. Throughout their work in the 1970s, they repeatedly rejected the black and red flags of their movement days in favor of the white flag of surrender. One could also see their rejection of a single meaning in their work as an ongoing reaction against dogmatism. And yet, they also seem to be perpetually working through these early experiences. The themes of joint struggle and interpersonal violence, for example, repeat over and over across their body of work as part of a cycle of violence, remorse, mourning, and new beginnings.

As Eiko and Koma each made the transition from activist to artist, each dove into the thriving Tokyo avant-garde art scene. They did not have far to go. The Shinjuku area of the city was home to both Waseda University and underground theaters. It was there that they each came upon performances by Tatsumi Hijikata’s dancers. By this time, the “new” avant-garde had been active for over fifteen years (in fact, some would say it ended by 1970). Dance and performance were integral parts of the Japanese avant-garde, significantly through Hijikata’s dance experiments that pushed the boundaries of the form.23 Hijikata was born in 1928 in Akita prefecture in northern Japan, where he studied modern dance with Katsuko Masumura, a student of Takaya Eguchi, one of Japan’s modern dance pioneers who had traveled to Germany in the 1920s to learn from Mary Wigman. Upon settling in Tokyo, Hijikata studied ballet, jazz, and modern dance with Mitsuko Andō, where he became acquainted with Kazuo Ohno, who along with Hijikata would become a major figure in butoh. The two performed together in Andō’s dances while working on other projects. In 1959 Hijikata had his formal choreographic debut with Kinjiki (Forbidden Colors), which he performed with Ohno’s son, Yoshito.24 Taking its title from a Yukio Mishima novel, the dance caused a stir with its shocking homoerotics and violence. Reaction to the dance prompted Hijikata, his wife Akiko Motofuji, and the elder Ohno, among others, to split from the mainstream All Japan Art Dance Association, which had presented Hijikata’s dance. At the same time, the notoriety that the piece attracted led to Hijikata being introduced into the avantgarde arts scene by Mishima himself. From then on, Hijikata’s work took place not in the context of modern dance but in the avant-garde arts community.

His experiments were known at first by the English term “experience,” then ankoku butoh 暗黒舞踏, and later simply as butoh. The word butoh (from bu 舞 “to dance” and toh 踏 “to step, to tread”) originally meant “stamping dance,” but that sense had long fallen out of use. Instead it appeared more commonly as butohkai 舞踏會, meaning a Western social dance ball. In the early 1960s the term ankoku buyo 暗黒舞踊 (“dance of utter darkness”) was coined to refer to Hijikata’s dance experiments, but was soon switched to ankoku butoh. Some people point to the word butoh’s signification of Western dance as a gesture to the intercultural influences on the dance, but I follow Baird’s suggestion that the sense of “foreign” implied by the term was employed not to reference specific dances, but rather to signal that this was something entirely unfamiliar, something that had not been seen before.25 The use of butoh rather than buyo allowed the group to clearly delineate themselves from Japanese dance (buyo), just as they had already drawn a clear line between their work and modern dance by leaving the All Japan Art Dance Association. As dancers such as Ohno, Akira Kasai, Akaji Maro, and others struck out on their own, they continued to call their work butoh, but the “utter darkness” qualifier was dropped along the way.26 Eventually the word came to encompass all the iterations and adaptations of the form developed by Hijikata and Ohno.

There is a tendency in the West to connect the “utter darkness” of butoh to the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, effectively ending World War II, but this link is simply not evident in the work of Hijikata and Ohno.27 Eiko & Koma do directly connect themselves to this moment, although this connection came explicitly many years later, only after Eiko witnessed the fall of the Twin Towers from their apartment window.28 Although the “utter darkness” of ankoku butoh was not in explicit reference to larger societal conditions, it may be useful to think of the postwar period broadly as one of utter darkness. While there are certainly aspects of this time unique to Japan, including a massive epistemological shift from understanding the emperor as divine to his being merely human, there are many ways this period in Japan is analogous to what was happening around the world. It was a time in which societies and economies were being rapidly transformed through large-scale industrialization and urbanization, the arts were being deeply questioned in part for their association with fascist ideologies, and radical politics spilled into the streets.

In its first decade, butoh’s search was for what could be expressed through the body and how. Marotti points out that from the start ankoku butoh lacked a recognizable style precisely because of its antiformalist nature.29 Throughout the 1960s Hijikata experimented with how to fundamentally alter the uses, techniques, and significations of the body, often through collaborating with other artists.30 In a series of “Hijikata Tatsumi DANCE EXPERIENCE Gatherings,” he shared the stage with dancers, writers, and artists, including Masunobu Yoshimura, Isao Mizutani, Shūzō Takiguchi, Tatsuhiko Shibusawa, Tadanori Yokoo, and Mishima. In the publicity materials, the programs, and the gatherings themselves, movement was but one aspect of the multilayered and multivalent productions, which drew heavily on surrealism and neo-Dada. Miryam Sas argues that intermedial practices like this not only led to unprecedented cross-genre collaboration and borrowing, but also “reconceived relationships among art, technology, and environment.”31 This kind of relationship is evident throughout Eiko & Koma’s body of work, particularly in the way they bring together their moving bodies with natural and built environments, video, musicians, and other elements.

Despite butoh’s resistance to explanation and interpretation, identified by Baird,32 there have been countless attempts to define the form by describing its aesthetic elements, categorizing major themes, or outlining creative processes or methodologies. Nanako Kurihara, who wrote one of the first in-depth examinations of butoh in the United States, defines the dance, in typical fashion, as a “contemporary dance form…. Typically performed in white makeup, with shaved heads, ragged costumes, slow movements and crouching postures.” She goes on to say that “butoh portrays dark emotions—suffering, fear, rage—often by employing violence, shocking actions and mask-like facial expressions that transform instantly from one extreme of emotion to another.”33 Her description of the form is a common one, but while it is frequently associated with the “original” butoh, I contend that these descriptions stem from later works, particularly those by Sankai Juku, an idea I expand on in chapter 3.

Eiko and Koma found their way separately in 1971 to Hijikata’s Asbestos Hall in the Meguro neighborhood of Tokyo. Koma says that Hijikata “had a big house and free groceries. I had nowhere to stay and no money. I was lucky and Mr. Hijikata said, ‘Okay, tomorrow you can come to my house.’ Sometimes very nice things start from coincidence, not your own determination. Three months after I moved into his house, Eiko, whom I had never met before, came into that same house for food and lodging.”34

Hijikata’s wife Motofuji established Asbestos Hall in 1950 as a live/work space with a bright, high-ceilinged studio and plenty of room for other dancers and students to stay. In 1974 the studio was transformed into a theater space, but until then it was used primarily for training and rehearsals. In exchange for room and board, Eiko and Koma and others trained with Hijikata and performed with other students in cabarets and theaters one, two, and even three times a night. Since 1959 Hijikata and Motofuji had been producing cabaret shows as a source of income that also provided financial support for Hijikata’s “real” dance work. These lucrative shows featured scantily clad men and women performing “artsy” dances for American GIs and Japanese men.

At this point, twelve years after his groundbreaking 1959 performance, Hijikata was a well-known and even notorious member of the Tokyo avant-garde arts scene. As such, it is no surprise that he would have attracted student activists and questioning young people, drawn to his daring acts and wild charisma. And yet 1971 was a peculiar time to be with Hijikata. His dance experiments throughout the 1960s, fueled by close collaborations with other avant-garde artists, had culminated in the 1968 performance Hijikata Tatsumi to Nihonjin: Nikutai no Hanran (Tatsumi Hijikata and the Japanese: Rebellion of the Body).35 That solo represented a major shift in his choreography, with its constantly transforming personas from a weary and diseased old man to thrusting, large golden cock-wearing virility, to young girl enthusiasm, but it was not yet the style for which Hijikata remains best known. That technique, a tightly choreographed and specific method of layering images to produce a movement vocabulary, announced with 1972’s epic Great Dance Mirror of Burnt Sacrifice—Performance to Commemorate the Second Unity of the School of the Dance of Utter Darkness—Twenty-seven Nights for Four Seasons, had not yet congealed. Some of the dancers who had been with Hijikata since the 1960s, such as Ko Murobushi and Bishop Yamada, were leaving to start their own projects. There is also a sense that women like Yoko Ashikawa were becoming more important in Hijikata’s work at that time, whereas his dances in the early and mid-1960s had been quite male centered. Although Hijikata’s dancers continued to perform between 1968 and 1972, both in “high art” venues and cabarets, this period is often overlooked by Hijikata scholars, in part because in retrospect Twenty-seven Nights overwhelms what came before it, and in part because Hijikata’s cabaret dances have for the most part not been taken seriously by scholars.36

Bruce Baird suggests that changes over time in Hijikata’s cabaret, in which his high and low art performances more and more came to resemble one another, can be attributed to a competitive cabaret marketplace. In that context, his shows got a reputation for being a kind of “weird, funky cabaret” in which female nudity appeared along with surrealist and Dadaist images. For example, Hijikata borrowed ideas from works such as Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915–1923), with its iconographic, geometric figures and accompanying mythic writings. Baird also attributes the growing similarities between the cabaret and stage works to Hijikata’s choreographic push to be two things at once, for example beauty and ugliness.37 In this context, it is not odd to think about avant-garde butoh and commercial cabaret in the same bodies. And while these performances remained dependent on women’s bodies being on display and still attracted older Japanese men wanting nothing more than to ogle young, nearly naked women, they also attracted young radicals like Eiko and Koma, who were interested in art that was challenging the political and social status quo. Both Eiko and Koma ended up at Asbestos Hall after having seen a performance at Shinjuku Art Village, one of the numerous underground theaters that populated the Shinjuku neighborhood of Tokyo at the time. Eiko in particular mentions being impressed by the way the women performers were willing to make themselves look ugly. This rejection of Japanese standards for female appearance and comportment likely presented an exciting alternative for someone already committed to challenging the status quo.

From all accounts, Asbestos Hall was an open and fluid environment at the time, where no one was turned away. In addition to apprentices who were committed to working with Hijikata for the long term, like noted dancers Yoko Ashikawa and Saga Kobayashi, there was a steady stream of students, radicals, and young artists coming and going at any given time. According to butoh scholar Caitlin Coker, “People would somehow get introduced to Hijikata, or they would just find the studio and show up.”38 There they would have an interview, or more likely a conversation with Hijikata, who would at the end of the talk tell them to come to keiko (training) the next day. At a time when frequent student strikes meant no school, young people needed something to do with their free time or something to help them recover from the intensity of the barricades. Moreover, the good economy meant that many young people could afford to float around from place to place without worrying too much about how they would eat or where they would stay.39 In a climate in which many young people were unsettled and searching for an alternative way of life, Asbestos Hall provided a viable, and likely exciting, short- or long-term option.

When Eiko arrived at Asbestos Hall, Koma had already been there for three months. They started working together after they were assigned to dance what was called an “adagio” at a cabaret. Neither Eiko nor Koma had studied dance seriously growing up, so they acquired dance and performance training on the fly. From all indications, this was a completely typical experience. According to multiple sources, people who showed up at Asbestos Hall were typically sent out to dance cabaret right away, sometimes even their first night at the studio. They would be given simple instructions, often by fellow performers, such as “hold this position,” or “move slowly,” or “if something goes wrong, take off your shirt very slowly.”40 As the performers gained more experience and improved their performance, they would be given more complicated choreography.

Asbestos Hall residents would dance in both cabarets and more “artistic” performances in small theaters like the Shinjuku Art Village, where they would typically wear a small thong-like garment with white makeup covering the body. Photographs taken by Tadao Nakatani in 1971 show a small stage with what looks like white sheets casually hung up at the back and stage right.41 The photos show frequent partner work, with a couple of patterns. In the first, one partner is on hands and knees while another partner sits atop the first. In a variation of this position, four dancers kneel side by side, flanks touching, to provide a base for a fifth dancer to recline, head thrown back, abdomen tensed, feet floating in the air. Other partner work took place in the vertical plane, as a man standing tall and straight held a woman with her legs wrapped around his neck, facing him, his face obscured by her pelvis. Another photograph shows a person laid back, rear lower ribs balancing on the supporting partner’s shoulder as the legs arc forward and toward the floor. Although the photos show static poses, one can imagine the performers slowly morphing from one position to the next, as Eiko & Koma do in their 1983 work Beam. Other photographs show slides projected onto Ashikawa and Kobayashi’s near-naked bodies as they kneel downstage center, calling to mind later work by photographer Eikoh Hosoe (Ukiyo-e projections, 2002–2003, and Butterfly Dream with Kazuo Ohno, 2006) as well Eiko & Koma’s 1976 White Dance, in which a drawing of a moth is projected onto and over Eiko.

After the late-night cabaret shows were over, the night was not yet at an end. Motofuji talks about everyone going to a local bathhouse to wash off the makeup, before rushing to catch the train home for a few hours of rehearsal before bed (see figure 1.1).42 Some people recall they were not given enough food to eat. And while the cabaret shows were quite profitable—payments averaged 10,000 yen per performance—the dancers turned over all their earnings to Motofuji and received only 500 yen back.43

FIGURE 1.1 Late night rehearsal at Asbestos Hall, Tokyo, 1972.Photo: Makoto Onozuka.

Eiko has described the studio as a temporary hideout from the chaos on campus and in the streets that characterized Japan, like much of the world, at the time. Three months after meeting, Eiko and Koma decided together to leave the autocratic environment under Hijikata to pursue their own projects. If as part of the student movements they were trying to challenge power, why would they stay with a man with a singular power? Although their time with Hijikata was brief, it is clear that Eiko and Koma absorbed his basic approaches to performance, the foremost being that it was possible to make a living dancing cabaret. Baird goes so far as to call cabaret, rather than a high art approach, constitutive in the development and spread of butoh and butoh-related movement beyond Hijikata, in that “acquisition of a kind of fundamental cabaret style is an important avenue” for dancers to make a name, and a living, for themselves.44 Certainly the experience dancing cabaret with Hijikata gave Eiko and Koma and other dancers like Ko Murobushi, Carlotta Ikeda, and Yumiko Yoshioka a way to market and support themselves when they first went to Germany in 1972 and France in 1977, respectively.45

Even though Eiko and Koma had less than a year’s training between the two of them, they were clearly excited by the possibilities performance offered and felt empowered to make their own dances. They put together a cabaret show under the name Night Shockers to make money to fund a trip abroad. At the same time, they put together “artistic” shows for which they created their own sets and costumes. The pair gave their first performance of original work at Waseda University in 1972, an event captured through four extant black-and-white photographs.46 All four images show Eiko, naked or perhaps wearing a small thong, her skin covered in clumped and flaking white makeup or rice flour. Koma is only present in two of the images. In one he wears a dark, knee-length kimono, and his skin is also covered in the white, flaking substance; in the other, he is in a side lunge, all in shadow, while she is captured mid-movement, head in profile, torso forward, the light from a projected image of a still life spilling over her skin. In these images, Koma is low to the ground, his kimono blending with the shadows and dark floor, whereas Eiko is upright, frontal, and often splayed open to the audience. Even when she kneels, she towers over Koma’s curled form. Though her skin appears to be peeling off her body, and her joints, ribs, and hip bones protrude, she is no fragile creature, but a concrete and rooted body, confronting her audience with a barely contained urgency.

In these images, elements from Hijikata’s cabaret shows are evident. For example, white body makeup and using the body as a screen for projections were common in Hijikata’s dances at Shinjuku Art Village at the time. On the other hand, the use of a kimono as a costume (which became a frequent element of Eiko & Koma’s performances) seems unrelated to Hijikata. Although he does wear a kimono in Rebellion of the Body, its specificity as a white bridal kimono suggests he is using it to play with gender, an idea furthered by the fact that he dons it backwards. In contrast, Koma never uses a kimono to cross-dress, and though gender is often obscured or blurred in Eiko & Koma’s body of work, this is often effected through nakedness, rather than clothing. Nor does Koma’s way of wearing the kimono resonate with the way Hijikata playfully misuses geta sandals in History of Smallpox. Instead, the kimono is simply something to wear that is easy to move in. Some of the kimonos that Eiko has worn over the years from her geisha grandmothers are markers of cultural context. They are worn simply and loosely (and sometimes backwards), without the conventional undergarments and belts.

At the same time that Eiko and Koma worked in cabarets as Night Shockers to save money to travel abroad, they started to make artistic work as Eiko & Koma, and took a twice-a-week improvisation class with Kazuo Ohno. Whereas the atmosphere under Hijikata was highly controlled—from what one should do onstage, to what one earned and ate offstage—the scene at Ohno’s home studio, high on a hill in the Kamohoshikawa suburb of Yokohama, could not have been more different than the urban Asbestos Hall. Ohno never told students what to do or how to dance, and in fact he often claimed that he had nothing to teach. He did not lead movement exercises or phrases, but rather talked about metaphysical concepts, art and artists, and dancers he had seen. From these inspirational words and image prompts meant to inspire movement, students were expected to find their own dance.

As a young man in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Ohno saw dancers such as La Argentina and Harald Kreutzberg perform, experiences he returned to again and again over the course of his life, including through the dance that made him world famous at age seventy-three, Admiring La Argentina (1977).47 However, it was not these experiences that prompted him to start taking modern dance classes; rather, it was his lifelong job as a physical education teacher at a Christian girls’ school that led him to study with the founders of Japanese modern dance, Baku Ishii, Takaya Eguchi, and Misako Miya, the latter two of whom had studied with Mary Wigman in Germany. Ohno had only just started to perform with Eguchi and Miya when he was called up for military service; he served for eight years, including one year as a prisoner of war. Upon his return to Japan in 1946 he resumed performing, and in 1949 he had his solo choreographic premiere. That same year he opened the Kazuo Ohno Dance Studio. For the next ten years, he made his own dances while participating in other people’s works. While dancing for Mitsuko Ando, Ohno met Hijikata. For most of the 1960s, Ohno stopped choreographing his own dances in favor of participating in Hijikata’s dance experiences. By the time Eiko and Koma met Ohno in 1971, he was performing live only occasionally and was making a series of experimental films with filmmaker Chiaki Nagano.48

FIGURE 1.2 Eiko & Koma with Kazuo Ohno after a performance in Tokyo.Photo: Courtesy of Eiko & Koma.

Even though Hijikata and Ohno had long collaborated, leaving one to study with the other was still an unusual move, even in the avant-garde world of butoh. Given Eiko and Koma’s political background and the general antiauthoritarian atmosphere among student protestors and young avant-garde artists, the attraction to someone who says, “I cannot tell you what to do, you have to figure that out for yourself,” must have been undeniable. Still, it was not easy work. Eiko remembers the trek from Sagami-Ohno, where she lived with her parents, out to Yokohama for Ohno’s twice-weekly class: the train ride followed by a walk up the hill, and the extra effort it took when it was cold. One night she arrived to find she was the only student. She describes the sweet awkwardness of receiving his full attention. He taught her how to bloom and wilt, placing his hand behind hers. She never forgot this first (and last) experience of Ohno’s one-on-one coaching.49

But even this self-driven, more open environment was not enough to keep Eiko and Koma rooted. Though they openly and lovingly credit Ohno as a teacher and had frequent contact with him until his death (see figure 1.2), they acknowledge that they were not among the disciples who worked intimately with him for years, if not for decades. Indeed, some of Ohno’s closest disciples became his caregivers and constant companions through his death at age 103 in 2010. Eiko and Koma’s early political activism instilled in them a fierce independence and an insistence on a “do it yourself,” or DIY, approach to art making, which made them bristle at the idea of being someone’s disciples. (Nor have they ever wanted to have their own disciples, thus their resistance to codifying a technique or transferring their repertoire to other dancers.) So, after studying with Ohno for less than half a year, Eiko and Koma left Japan together. Having already left school, they had a drive to do their own thing and felt that they needed to get far away in order to have the space to do that. Eiko once suggested to me that extended proximity to greatness results in just serving that greatness. Obviously they would not be who they are or be making the work that they do without the formative experiences living at Asbestos Hall or training with Ohno, however briefly. But they also craved experiences beyond the islands of Japan, and in late 1972 Eiko and Koma set off to continue their movement research elsewhere.

White Dances

The early 1970s was a period of major departures for Eiko and Koma, who were at that point on their way to becoming Eiko & Koma. They left school, two major figures of avant-garde dance, and finally even their country. Suzanne Carbonneau emphasizes that Eiko & Koma were not traveling in order to perform. “Performing was, rather, a strategy for discovering the world … while they ‘researched [their] lives.’”50 Although she seems to mean this quite literally—dance was a means for the pair to see the world and travel beyond Japan—her phrasing quite nicely points to the way that Eiko & Koma have since used their dance to understand their relationship to time, history, humans, and nonhumans. In a manner prescient of their future movement style, in which a specific beginning or end is less important than noticing and participating in the ever-evolving moment, the pair embarked on a slow journey whose destination was not entirely clear at the outset, departing Japan on a boat bound for the Soviet Union. The one thing they knew for certain was that they had made a conscious decision not to go to the United States. On the one hand, their opposition to the Vietnam War precluded the United States as a destination; going there, they felt would signal an implicit acceptance of the government’s actions. On the other hand, they had a sense that everyone was going to the United States at that point, and indeed a number of Japanese avant-garde artists, including Yoko Ono and Yayoi Kusama, had been welcomed into the New York art scene in the 1960s. Spain was one possible destination—Eiko remembers studying Spanish on the ship—however, they ultimately rejected that option because of their political opposition to Francisco Franco’s fascist dictatorship. After their ship docked, the pair then took a train to Moscow. Somewhere along the way they decided to go to Germany, and in Moscow they boarded a plane to Vienna, where finally they took a short train ride to Munich.

Ending up in Germany was not random, however. In a discussion about this period of their lives, Koma pointed to the long history of artistic exchange between Japan and Germany, and in particular to the links between their teacher, Ohno, and Mary Wigman’s modern dance style.51 Cultural exchanges among Japan and European countries had in fact been commonplace since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when the Japanese began a concerted effort to show their country, policies, and products to be on a par with those of the Western powers, often through the adoption or adaptation of Western practices and conventions. At the same time, all things Japanese enjoyed an enormous popularity in the United States and Europe, prompting artists there to themselves adopt or adapt Japanese techniques. For example, the aesthetics of noh circulated to Europe and were incorporated into the practices of playwrights and theater directors such as W. B. Yeats, Jerzy Grotowski, and Samuel Beckett; in turn, Japanese theater practitioners of the 1960s and 1970s were themselves influenced by some of these same European artists.52 It was not unusual then that the Japanese pioneers of modern dance studied in Europe in the 1920s, some with Mary Wigman herself, and introduced German “new” dance to Japan. Koma remembers Ohno talking to them about Kreutzberg and Wigman. Koma and Eiko themselves discovered pictures of Dore Hoyer in the Music Library at the Tokyo Bunka Kaikan 東京文化会館. Of these German dancers Eiko says, “They were like kind of romantic figures for our soul. We couldn’t romanticize our own teacher because we were too rebel [sic] ourselves. We were always questioning; and there was some senior students who look at Hijikata and Ohno like this [looking at them as if they were god]…. I just couldn’t get involved in that because we were always questioning. But those photos became instead my kind of romantic … where my romantic idea can go forth.”53

There was something in these dancers, whom they only knew through photos and stories, which resonated with the political focus on the individual, that contributed to Eiko & Koma’s worldview. They had seen Martha Graham and had read about Merce Cunningham, which gave them the sense that they knew what was happening in American modern dance. But at that point, Wigman’s style was out of favor and even disappearing, and Koma says that in that context they were interested in searching out the roots of what was by then called Ausdruckstanz.54

Arriving in Munich soon after the 1972 Olympics, the city had a vibrant young people’s culture that attracted the dancers. Almost immediately, they self-produced a two-month, late-night run at a small theater called ProT, while also continuing to support themselves with cabaret shows.55 Upon arriving in Germany, Eiko had written to Mary Wigman about the possibility of studying with her and had received her response that she was too ill to teach.56 At their performances they distributed a flyer asking for leads to where they could study Wigman’s technique. One day an audience member suggested that they contact Manja Chmiel in Hannover. Chmiel, a longtime assistant to Mary Wigman, had developed her own career as a solo dancer and had a school there. Eiko wrote to her immediately, and when they received a letter in return inviting them to Hannover, they packed up the old car they had acquired and moved north.

Upon meeting, Chmiel asked them to dance for her. Eiko reports, “Whether she liked it or not, I don’t know, but she did say immediately after that that we shouldn’t be learning about choreography from her.”57 Despite this recent statement, Eiko said in a 1998 interview with Deborah Jowitt that Chmiel gave them feedback that helped them “maximize the visual and emotional impacts” of their dances by paying attention to lighting and paring down their movements.58 In addition, Chmiel “encouraged them to train their bodies for expansion and life so that they could transmit movement on a larger scale.”59 She arranged for the dancers to take ballet classes for free at the Stadthaus in the mornings and to take her modern classes in the evenings. In the afternoons, she gave them access to her studio to rehearse for their regular late-night cabarets and for occasional campus and museum performances at the Studentenheim and the Kunstverein.

According to Eiko & Koma, however, the most important thing Chmiel taught them was not dance technique, but their power as a team; until that point they had viewed their partnership as merely a tool for survival and a step to becoming solo dance artists. She gave the duo the time and space to develop their work and pushed them to take their partnership seriously by entering them in a noted competition (alternately referred to in materials by and about Eiko & Koma as the Kölner Preis, the Young Choreographers’ Competition, and the Cologne Choreographers’ Competition), with Kurt Jooss as one of the judges. Eiko & Koma were among the three finalists in the competition and were invited to perform at the Cologne Opera (see figure 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3

White Dance, Young Choreographer’s Competition, Cologne Opera, Germany, 1973.Photo: A. Loffler.

That show, like all of their performances in Europe, was called White Dance.60 The title acts as an expression of independence from their first dance teachers, Hijikata and Ohno. Eiko & Koma’s dance, the title suggests, is specifically not the “utter darkness” of their butoh teachers, nor that of the failed student movement. The color white moreover provided a powerful contrast to the black and red flags of various political movements. In Eiko and Koma’s activist histories, as well as in the times in which the piece was made, there was a significant resonance of political allegiance with the color white, especially in opposition to black (anarchism) or red (communism). White also calls to mind the act of surrender, death, and ritual. Suzanne Carbonneau suggests that in “embracing whiteness as an antidote to the black uniforms of anarchism they had worn in the student movement, they meant whiteness to signal their decision to leave their pasts behind in order to create anew.”61 The choreographers explicitly took up the white flag of surrender almost a decade later in Event Fission (1980), an act that calls to mind John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s 1973 declaration of the conceptual country, Nutopia, with its white flag of surrender to peace. While calling their dance “white” implied a strong sense of rejection, it also provided continuity, for example through the white makeup used in both traditional Japanese performance and butoh. In this way, the literal whiteness of their dance provides a connection, like that sought by some other avant-gardists, reaching back beyond recent history. Indeed, one of the few books the dancers took on the road was Zeami’s late fourteenth- to early fifteenth-century treatise on noh, the Kadensho.62

The movement in these White Dances was not set, although Eiko & Koma did have a loose score of movements to draw from and an order of the movements agreed upon in advance. According to Joan Rothfuss, “The events combined moves they had learned from their various dance teachers—Kazuo Ohno, Tatsumi Hijikata, and others—with such Dadaesque actions as cutting their hair, throwing raw eggs, cooking fish, dragging a bundle of carrots, and painting their bodies with dough.”63 In Koma’s words, “We were just trying to do something strange.64 Remnants of these dances remain in photographs from performances in theaters and museums in Germany and the Netherlands, and in a recently discovered twelve-minute color film—minus sound track—made in Amsterdam circa 1973, which is the earliest known footage of Eiko & Koma (see figure 1.4). The film alternates between performances and scenes of Eiko and Koma in their kitchen, revealing the closeness of their communal relationship in life as well as in dance. While their words are lost, their dancing includes movements strikingly similar to Hijikata’s early 1970s choreography for Ashikawa and Kobayashi as well as original vocabulary that would later appear in Eiko & Koma’s White Dance (1976) and Fur Seal (1977).

FIGURE 1.4

Still from first known video footage of Eiko & Koma, Amsterdam, circa 1973.Courtesy of Eiko & Koma.

Despite Koma’s seeming dismissal—“just trying to do something strange”—in fact they were clearly doing something radical and shocking, and even profound, with their bodies, evidenced in the enthusiastic reception that greeted them in Europe and North Africa from 1972 to 1974. Those performances moved easily among late-night theaters, opera houses, museums, and performance festivals, echoing the way that Hijikata’s radical dances could also read to multiple audiences, both high art and bawdy at the same time. Certainly in Europe there was an added layer of Orientalism impacting the reception of their work, in the sense that “Oriental” read as high culture. Eiko concedes that “the fact we grew up in postwar Japan remains significant and essential in the ways we think and work, more so than the fact we studied and worked in Germany briefly. You know, sometimes you are reminded of what you have absorbed early on when you are away from where you grew up. But we were not cultural exports and we didn’t play for exoticism. I think we are careful not to.”65

In negotiating their cultural and national differences through dance, the pair found themselves having to work with and against being received as the Other, no matter where they were. In any case, their singularity as Japanese dancers in Germany in the early 1970s, drawing from an as-yetunseen-outside-Japan movement style, helped them stand out to audiences and mentors alike.

Their high-profile performance at the Cologne Opera resulted in other artists seeking them out and led to further performance and teaching opportunities beyond Hannover. For example, Lucas Hoving saw Eiko & Koma perform in Amsterdam and invited them to teach a master class at the Rotterdam Dance Academy, where he was then a director. Hoving, famous for his years spent dancing with José Limón, strongly suggested that they go to New York. At the time Eiko & Koma were not even sure they would continue to dance beyond their time in Europe, due in part to Eiko’s persistent ankle injury. Hoving, however, convinced them not to give up dancing until they had been to New York. Though the time with Chmiel and Hoving was brief, their influence, like that of Hijikata and Ohno, would continue to resonate throughout Eiko & Koma’s career.

During their time in Europe, Eiko & Koma were constantly on the move. They had a cheap car, and as soon as they heard about a new opportunity, they would head off. After spending some time in the Netherlands and forming the Linden Gracht Dance Laboratory with Mitsutaka Ishii, the pair toured in France, Switzerland, and Tunisia. In Tunisia one of their audience members urged the pair to perform in New York and suggested they contact her cousin, who turned out to be Beate Sirota Gordon, then performing arts director at the Japan Society. Gordon is a significant figure in US-Japanese relations.66 At age twenty-two, Gordon participated in the drafting, translating, and negotiating of the Japanese constitution and was instrumental in enshrining equal rights for women in that document. In addition to the Japan Society, Gordon also served as performing arts director at the Asia Society. In her role at the Japan Society beginning in the 1950s, Gordon was responsible for introducing both traditional and contemporary performing artists from all over Asia to American audiences. Both the cousin and Eiko wrote to Gordon, who was hesitant to present performers whom she had not seen and chosen herself. Despite her reservations, she decided to proceed with booking Eiko & Koma based on her cousin’s recommendation, provided they had round-trip tickets and money deposited in an American bank account for living expenses.67 The dancers agreed, then returned to Japan to work, raise the required money, and deal with Eiko’s ankle injury. During that time, they studied again with Ohno and began to work on a piece to perform in the United States the following year.

White Dance

Eiko & Koma arrived in the United States in April 1976, ready to premiere White Dance.68 By this time the Vietnam War had ended, and the pair were no longer conflicted about entering the country. Although the dance they made for their American premiere shared a name with their European performances, the dancers consider the 1976 piece their first set choreography. They felt that a high-profile venue like the Japan Society called for “a little more choreographic effort,” which included “actually deciding on music, costumes and program notes.”69 The dancers spent their time in Tokyo processing the movement, choreography, and expression lessons learned during their years in Europe, both through formal instruction and through their extensive performance experiences. Premiering five years after the pair met at Asbestos Hall, White Dance was the culmination of the duo’s first period of movement and life research.

A sense of momentous transition between their first five years working together and their arrival in America was captured in a version of their biography frequently used in programs in their first few years in the United States:

EIKO & KOMA began working together in 1971 while members of Hijikata’s company in Tokyo. After a Tokyo debut they traveled to Hannover, Germany, in 1972 where they met and studied with Manja Chmiel, a disciple of Mary Wigman. For the next three years EIKO & KOMA performed throughout Europe and Tunisia. A year’s added study in Yokohama with Ohno Kazuo prepared them to continue their dance in America.70

Indeed, the teachers and mentors enumerated in this biography remained consistent from this point forward in Eiko & Koma’s career, although mentions of Hijikata did diminish over the years, a fact Eiko explains by noting that their relationships with Chmiel, Ohno, and even Hoving were ongoing, while the one with Hijikata ended when they left Asbestos Hall. They never saw him or were in touch with him again.71 While the pair would continue their choreographic experimentation through the early 1980s, a process discussed in detail in chapter 2, their arrival in the United States was a major turning point in their work.

Two years of performing around Europe had taught them valuable lessons about how to generate opportunities for themselves. Before departing Japan, Eiko sent letters to all the Dance Magazine correspondents across the United States, letting them know of the duo’s impending visit and asking if anyone would help them set up a performance. Irene Oppenheim, then a West Coast reviewer for Dance Magazine and a critic for local Bay Area papers, responded, inviting the pair to contact her once they arrived, so they arranged a layover in San Francisco on their way to New York. Oppenheim recalls trying to figure out what their work was like during that first meeting: “I would ask them, ‘does it use kimonos?’ And they would say, ‘Yes, but it’s not traditional.’” The critic was quite taken by them, despite the dancers’ halting English, remembering, “They were very young and very charming and very beautiful.”72 By the end of the meeting, Oppenheim agreed to arrange an invitation-only performance in a former garage of a small private school the coming weekend in order to accommodate Eiko & Koma’s New York schedule. In addition to securing the venue and recruiting her friends and acquaintances to attend, she recalls being given the peculiar task of purchasing two hundred pounds of potatoes for use in the performance. Did the dancers really like to eat potatoes?

As a transitional piece in Eiko & Koma’s career, White Dance reflects the style that characterized the experimental dances they performed in Europe while introducing new choreographic elements. The dance also represents their efforts to connect with an entirely new audience whose context for what they were seeing was different than that of audiences in Japan or Europe. “When they first came [to the US] they really were pioneers,” says Oppenheim.73 Indeed, the pair arrived in the United States, and even Europe, before butoh or any similar movement practices were known outside of Japan, with the exception of a handful of photographs in William Klein’s 1964 book, Tokyo. For American audiences, the context for Eiko & Koma would have been Japanese performance artists like Yoko Ono, or American avant-garde performance, such as what Oppenheim talked about seeing in San Francisco at theaters such as the Theater of Man.74 Others found a context for what they saw in the “early moderns.” Janice Ross, for example, in a review of Eiko & Koma a year and a half after their San Francisco debut, describes their work as “an honest and forceful amalgam of the raw beauty and violence of Mary Wigman’s expressionistic theater and the metaphorical density and fragility of Asian art.”75 This view was likely shaped by press releases for the pair that described their work “as avant-garde dance in the Japanese manner, [showing] the influence both of Japanese traditional and German modern dance.”76 Whatever the context of the individual viewer, Oppenheim says, “I think that a lot of their appeal, at least in the early days, was that they were so exotic to us.”77 At that time, there was still a strong division between “ethnic dance” and “modern dance”; as Japanese people performing avant-garde dance, Eiko & Koma were perceived as a rarity.

Like their embrace of the political meanings of “white,” Eiko & Koma incorporate other gestures of opposition as part of their attempt to figure out how to further their own political questioning through dance. The US premiere of White Dance was supplemented by the appearance of a loose adaptation of Mitsuharu Kaneko’s uncredited 1948 poem Ga 蛾 (Moths) in the program. Written during the American occupation of Japan and postwar reconstruction, the poem speaks to glimpses of beauty and determination amid the overwhelming inevitability of death. Eiko’s adapted translation reads in part:

To live is to be fragile

So is it a fault to nurture a dream?

Oh moth! what is life to you?

You’ve been exhausted ever since you lost your cozy pupa,

You’ve carried the weight of time upon your back

And gasped for breath

While taking a rest

After such a short journey,

Then started on another voyage

Into an unknown future.78

Kaneko (1895–1975) is noted as the only Japanese poet to write antiwar poetry during World War II, including “Bald,” an account of his attempts to help his son fail his draft physical. Kaneko is also considered an outsider in Japanese society, due not only to his extensive travels abroad, but also to his writings, which eschew and outright reject societal conventions. Taking up these words, in English translation, over a quarter of a century later, Eiko & Koma signal their own desire to “nurture a dream” with their dance, even as they acknowledge the ongoing violence and absurdity of life at the end of the Vietnam War.

Absurdity and opposition are both evident in White Dance’s opening scene. A version of the madrigal “The Agincourt Carol” plays as Eiko sits slumped forward in a printed casual kimono center stage, and Koma strikes a flouncy pose upstage left.79 No one moves for what seems an eternity, and then Koma begins to carefully pick his way around and across the stage, stepping lightly on his toes and occasionally flicking his foot back with a flourish to reveal his bare buttocks through a slit in the back of his bright red short kimono, worn backwards. Satisfied with his trip around the stage, he exits purposefully, having never acknowledged Eiko’s presence. In Kaneko’s poem, “Opposition” (not quoted in the program), the poet lists all the things to which he is opposed, including school, work, and “the Japanese spirit.” “I’m against any government anywhere / And show my bum to authors’ and artists’ circles,” he writes.80 For those familiar with Kaneko’s poetry, Koma’s mischievous reveal of his own bare bottom in White Dance recalls the poet’s desire to challenge every element of society. This cheeky behavior is furthered in publicity materials and programs for the dance. A photograph of Eiko shows her suspended midair, leaping yet posed almost as if she is seated in a chair. Her torso is bent all the way forward, feet flexed, knees bent, her whitened buttocks and legs revealed by her kimono as it floats above her body. Another frequently reprinted photo shows Koma facing away from the camera, his butt sticking out from a slit in his mid-calf-length kimono donned backwards, legs in wide parallel.81 This “showing of the bum” resonates with Eiko & Koma’s days as student activists, but here it is more playful than militant, more sassy than offensive.

But White Dance was not limited to absurd and cheeky moments. Eiko’s slow-moving solo, which makes up the middle section of the dance, ushers in a contemplative mood. Balancing on her tailbone, she reclines midstage, allowing her four limbs to billow around her until it seems there is nothing else happening in the world except this small dance. Eiko developed this solo when she was suffering from her ankle injury, so the movement was initially functional. The solo, however, demonstrates the value of rootedness in their work, not only as a visual anchor, but also in terms of duration of time. Even when she eventually rises to the vertical plane, allowing projections of photos of medieval Japanese patterns to suffuse her and her surroundings, her sustained movement-in-stillness is captivating.82

In contrast to Eiko’s intense, grounded presence in the center of the stage, Koma often bounds across the space. When the two are reunited onstage, they move not in unison but rather in tension with one another. Their taut muscles bristle even as their joints bend in unexpected angles, only to rebend in other configurations again and again. A kick or a slap explodes out of stillness. Then, near the end of White Dance, it suddenly becomes clear why Oppenheim had to buy all those potatoes. Koma rushes onstage, a huge sack over his shoulder, as potatoes cascade to the ground in a series of rolling thumps, kicking up small clouds of dust as they fall. The tubers have scarcely rolled to a stop, scattering across the stage, when Koma scurries back with another sack over his shoulder, repeating the dramatic potato drop once, twice, before throwing the canvas sack in a wide arc toward the wings and careening into the back wall. Meanwhile, Eiko holds the center of the stage, her deep stance rooting her in place as she pulls her hands into fists at her hips, elbows jutting backwards, as if ready to fight. Robert A. Fredericks, reviewing the Japan Society debut performance for Dance Magazine, wrote of the potatoes: “After recovering from the initial shock, I found it profoundly exciting. Not only the sight of those potatoes rolling around and spilling over the edge of the stage but the dust that flew from them, the sounds they made as they slipped from the bags and thudded on the wooden floor, all contributed to the effect.”83 The multisensory engagement demanded by the potatoes—how they looked, sounded, smelled—draws attention to Eiko & Koma’s neo-Dada-style use of these everyday objects.

Even as it revels in the nonsensical—“Why potatoes? What have they got to do with moths?”84—White Dance also signals an attention to cycles of living and dying and the attendant violence thereof that later became a central concern for the choreographers. Deborah Jowitt saw struggle and combat in the dance: “But their work isn’t pretty or sentimental; it’s pervaded with horror, studded with moments of violence.”85 Fredericks noted how Koma “swatted [Eiko], and not gently.”86 Oppenheim saw a violence in the piece that was less shocking than it was moving. For her White Dance evoked a deep sadness that felt linked to Vietnam, a war that had ended only the year before.87

Perhaps more significantly, the work shows Eiko & Koma trying to determine what their choreographic project will be. The piece stages modern dance influences such as Koma’s enthusiastic leaps and Eiko’s striking side attitude alongside a startling cascade of potatoes and alternately meditative and disturbing minimalist movements. Shoko Letton suggests that the “ugly” movements can be traced to Hijikata and the “beautiful” ones to Ohno;88 this binary interpretation is in line with many analyses that contrast Ohno’s “angelic” works with Hijikata’s “demonic” ones. Rather than staying with this dichotomous view, Kaneko’s “Opposition” offers another way to approach these contradictions. Kaneko writes: “[T]o oppose / Is the only fine thing in life. / To oppose is to live. / To oppose is to get a grip on the very self.”89 In this way we can see the oppositions in White Dance—the ugly and the beautiful, the sublime and the absurd, the meditative and the explosive all together in this one piece—as not merely an amalgamation of previous influences, but rather a way of coming to understand Eiko & Koma.

By the time Eiko & Koma ended their trip to the United States, they were no longer just using dance to see the world, but were making a concerted decision to become artists. Their bodily research had led them beyond experimenting with Hijikata and Ohno’s movement approaches to finding their own unique combination of extended stillness with moments of absurdity that unfold over time into a profound engagement with existential matters. Their experiences in New York in particular led them to see a place for themselves in that city’s experimental downtown dance scene, a possibility they had not seen for themselves in Tokyo. When they returned to Japan, it was to arrange cultural exchange visas, with Gordon’s help, for their return to New York, where they settled in 1977. The following chapter examines Eiko & Koma’s first five years as residents of New York City, with a focus on the dances they created during that time, one new piece each year, and the various artistic influences they absorbed.