Читать книгу Flowers Cracking Concrete - Rosemary Candelario - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

“GOOD THINGS UNDER 14TH STREET”

When Eiko & Koma settled in New York, the city, like many other major US cities, was experiencing what was referred to as an “urban crisis.” So-called white flight to the suburbs, coupled with systematic economic disinvestment and government neglect, had left abandoned swaths through cities like New York, and particularly neighborhoods like the Lower East Side, which had traditionally been working class and immigrant communities. As landlords abandoned and even destroyed their buildings, and residents fought to stabilize their neighborhoods, artist subcultures were able to take root and flourish downtown thanks to low or no rent on commercial and residential spaces.1 According to Christopher Mele, “Downtown described not only a place but an aesthetic or genre of music, dance, fashion, hairstyle, art, and performance.”2 In particular, Mele claims, the downtown scene was defined in opposition to “uptown,” which was epitomized by the famous nightclub Studio 54. While uptown stood for wealth, excess, commercialism, celebrity, and privilege, downtown stood for alternative, experimental, radical, underground, and weird. The economic opportunity to live and create work inexpensively downtown allowed clubs, galleries, and performance spaces to develop as crucibles for a new art scene in which punk music, visual arts, film, and performance intersected.

Koma’s description of the contradictions of mid-1970s New York paints a vivid picture of what he and Eiko encountered when they landed in the city:

When we arrived here [in New York] in 1976, we had the feeling that somehow we missed a very important art movement. Already, Judson [Dance Theater] was over. We could see that Soho was developing into artists’ lofts by then. We couldn’t find Yayoi Kusama [she lived in New York from 1956 to 1973, when she returned to Japan] or Allen Ginsberg—though we did find Ginsberg later. And the city was bankrupt. Garbage was everywhere. People were lying down everywhere on the street. It was a weird time.3

Despite the feeling of having missed an era, Eiko & Koma in fact arrived in New York in the middle of a major boom in American postmodern dance, often referred to as the downtown dance scene.

In remarks made at a 2012 event sponsored by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Koma recounted his memories of being told that nothing good was happening above 14th Street. “So I tried to look for good things under 14th street,” he says. “I visited Meredith Monk, the experimental composer and vocalist. She was performing at her loft. And after that we played baseball together in a vacant lot. I remember Tricia Brown performing at her loft. David Gordon was also performing at his loft. Nobody had money. Lucinda Childs was performing her solo piece without any music at Danspace.”4

As Koma’s narrative indicates, downtown Eiko & Koma found themselves immersed in an active group of artists who, like the pair of new New Yorkers, were using their art to imagine new ways of being in society. Even when a specific political message was absent from the work—and it often was—the act of identifying with “downtown” was not just a geographic orientation, but a fundamentally political one. During this time, Eiko & Koma began experimenting with a variety of movement vocabularies, novel themes, and interdisciplinary collaborations with their new artist friends. Their pieces infused the then predominant mode of “dance for dance’s sake” with uncommon qualities such as extended stillness and overt expressivity. Moreover, Eiko & Koma’s combination of recognizable postmodernist characteristics such as nonlinearity and juxtaposition with novel (to the United States) ways of moving their bodies led to the pair quickly becoming critically acclaimed mainstays of the New York avant-garde.

I argue that the dances Eiko & Koma made in their first years in New York—Fur Seal (1977), Before the Cock Crows (1978), Fluttering Black (1979), Trilogy (1979–1981), and Nurse’s Song (1981)—participated in the inherent social critique that characterized much of the late 1970s downtown arts scene. Although these works sometimes employed radically different styles (belly dance, punk, hippie), reviewers nonetheless came to expect a particular kind of quality of movement from Eiko & Koma and did not hesitate to critique dances that did not live up to their expectations. It is not my intention here to say the reviews were right or wrong, but to point out how a misunderstanding of Eiko & Koma’s choreography was beginning to accrue even around these early works. As I show in chapter 3, this misunderstanding had a major impact on their dances being seen as Asian rather than Asian American. The danger of reading Eiko & Koma’s choreographic preference for slowness and stillness as a culturally determined aesthetic attribute rather than the bodily articulation of a fundamental oppositional politics is that dances deviating from a particular style are then rejected on that basis, without a consideration of how they might be attempting to politically achieve the same thing as previous dances, simply through different means.

This experimental period in Eiko & Koma’s choreography coincides precisely with a transitional period in American experimental dance observed by critic Marcia B. Siegel. In the introduction to The Tail of the Dragon: New Dance, 1976–1982, Siegel argues that the changes that took place in the dance scene between 1976 to 1982 were not the result of a specific and visible revolt, as had been the case with Judson Dance Theater a generation earlier,5 but their effects nonetheless resulted in a visible and distinct change in American experimental dance. According to Siegel, social and cultural changes in the United States produced dancers who were concerned with dance itself, expressive not abstract, aggressively physical not pedestrian.6 Her description of how the height of arts funding in the 1970s (before the beginning of the Reagan era) enabled the wider circulation of experimental dance while also requiring it to become standardized is particularly worth noting, especially since this is the precise climate in which Eiko & Koma began performing in the United States and during which they made a name for themselves. Siegel notes, “Subsidies underwrote dance performance and dance touring across a spectrum of taste wide enough to encompass experimental artists…. In some ways the experimental companies were better prepared to reach a wide audience than traditional groups. They were committed to flexibility, not wedded to proscenium spaces or rigid programming; they could dance in parks or schools, they could include local performers, improvise, and adapt to the conditions they found. But little by little, the diversity, the unpredictability, the strangeness that was so much a part of experimental dance was tamed and toned down.”7 She points out how the exigencies of these increased touring opportunities produced a need for set repertory pieces that fit into allotted time slots and could be billed as either well-reviewed hits or exclusive premieres.

Eiko observes that the kinds of needs described by Siegel had a specific impact on their choreography. Rather than presenting a full evening, as they had done on the European festival circuit and as they did in their first dances in the United States, Eiko & Koma began making shorter works. “Here, for the first time we were asked to make a piece and it doesn’t have to be a full evening, which allowed us to think differently. And I think that’s a choreographer’s thinking, and that’s why I feel like at that point we are also are very much a part of American modern dance.”8 This chapter focuses on the transitional period of Eiko & Koma’s first five years in New York to demonstrate how their work during this time was both impacted by and incorporated into the larger contexts of American postmodern dance, avant-garde arts and music, and late 1970s politics.

Fur Seal

When Eiko & Koma returned to the United States from Japan in late spring 1977, a little over a half a year after their first trip ended, they brought with them an entirely new dance, Fur Seal. In this piece, the dancers playfully alternate between embodying seals—lying on the ground, upper body raised forward and up, hands working like flippers—and exploring the full use of their human legs through walks, runs, jumps, balances, and lifts that they may have picked up during their time studying with Manja Chmiel a few years earlier. The sixty-minute performance is accompanied by whale songs, Schubert, and “I Am the Walrus” by the Beatles, punctuated by frequent silence. An encore was performed to Bob Dylan’s “One More Cup of Coffee.” The dance is representative of the experimental, high energy, and sometimes absurdist work of Eiko & Koma’s first years and at the same time foreshadows the pair’s abiding concern with nonhumans and nature, particularly American landscapes. A 1976 trip to see harbor seals mating on the beaches of northern California impressed Eiko & Koma and inspired them to work on this new dance in Tokyo with the express intention of premiering it in New York.

Fur Seal marked a crucial break from Eiko & Koma’s long-term work with White Dance. The new theme spurred them to expand their movement vocabulary and explore new ways of staging their work. At the same time that they broke new choreographic ground, the use of another Mitsuharu Kaneko poem (from which they took their title) and reference to a nonhuman subject provided some continuity with their previous piece. In the case of Fur Seal, however, seals were not the metaphorical inspiration that the moths had been for White Dance, but a real-world one. The experience of seeing and smelling the seals in California must have resonated strongly with Kaneko’s evocative stanzas:

The sunlight beats down like sleet

Today is their wedding feast

Today is their big holiday

All day long they wallow in the mud

Ceaselessly bowing and curtseying

Rubbing their fins together

And rolling their bodies like carrels

Fur Seal

How foul-smelling is your breath

How slimy is your back

Clammy as the abysmal depth of an open grave

Your body is ponderous as sand-bags

How mediocre, how banal you are

Your somber elastic shape

Your dolorous lumps of rubber

Bob and sink in the sea

In the sorrowful rays of the evening twilight9

The poem focuses on seals at the time in their life cycle when they leave the water, through which they easily glide, for an awkward and lumbering sojourn on land spent mating and gestating. Despite the sunshine and celebratory air Kaneko lends the seal mating, his repugnance toward the creatures is palpable. His aversion to them reveals a sort of existential horror; he seems to ask, “Is this all we are?”

Whereas Kaneko encountered the seals as a disdainful observer, Eiko & Koma approached the creatures with a sense of bodily curiosity. Eiko described the seals in a newspaper preview of their dance: “We saw how they moved. They don’t need their feet very much, but move with their whole bodies. They are such lazy things, but they are always looking at you. And they are recreative. They know just enough of life; I think we know too much. We have so much information, we don’t know what to do with it. They know. We were interested in the way the seals eat, too. They don’t spend their whole time finding food—just a little. Then they are free to play and move. That’s where our dance came from.”10 What would it require to embody the seals? How could the dancers wallow, bow, curtsy, roll, bob, and sink on the seals’ “recreative” terms? After the fragility of moths, the ponderous, fleshy substance of seals must have presented a tempting challenge. Eiko & Koma roll, scooch, contract, and undulate, all without the use of their hands, arms, or legs.11 Eiko & Koma become all trunk, like the set piece hanging downstage left: a tree trunk stripped of all branches, leaves, and roots.12 Land-bound locomotion for both the seals and these seal-dancers is an awkward struggle, expending maximum effort for minimal forward motion.

Fur Seal had its premiere at the Riverside Dance Festival in New York City in June 1977. The festival program included the Sophie Maslow Dance Company, the Isadora Duncan Centenary Dance Company, the Rudy Perez Dance Company, guest choreographer Hanya Holm, and many others. In a bill that heavily featured modern dance, and particularly early modern dance, Eiko & Koma must have stood out as strikingly unfamiliar.

Upon first seeing Fur Seal, Jennifer Dunning wrote, “You watch, unable to look away,” adding, “There is no one like these two dancer-choreographers. Theirs is the intensity of strong, white light, exhausting but beautiful.”13 These sentences from a short two-paragraph Dance Magazine review (part of a much longer piece addressing a number of concerts) were used extensively in Eiko & Koma’s publicity materials for the next several years and came to define the pair’s early work in the press, framing their work as singular, something to which one is inextricably drawn.

For many audience members, the opening section concentrated the kind of experience Dunning described. When lights come up, the stage remains only dimly lit. One can discern two figures, one reclining, and one upright next to the tree trunk that hangs in the space. Dark costumes and a dark stage blend together, against which exposed fragments of bodies—lower legs, a torso, an elbow—pop out. And then nothing happens. Nothing at all. Like the seals Kaneko accuses of wallowing and laziness, Eiko & Koma seem to be doing nothing but existing on the stage for minutes at a time. Eventually it becomes evident that they are not still, but rather their movement is infinitesimal, proceeding at an unhurried pace. Beginning curled up on her left side, Eiko takes all the time in the world to transition to her stomach, arms tucked under, lower legs pointing up, face out to the audience. I cannot call what she does rolling, because that suggests momentum and gravity and a certain inevitability that cannot be assumed in this case. She then drops her feet to the left, millimeter by millimeter, eventually bringing them back up, then repeating the process on the other side. During the whole time, silence reigns. Still Koma stands, perhaps a foot away but in another world. He seems to lean on the tree trunk, eventually taking it off its axis and revealing its suspension. Finally, gravity takes over in both cases: the trunk swings back and Koma begins to play with it, even as the weight of Eiko’s lower legs finally takes over, provoking a response from the rest of her body. From this point, approximately five minutes into the dance, the pace picks up, but the experience of suspended time, of watching with bated breath, suffuses the rest of the performance, imbuing even periods of whimsy and hyperactivity such as the seal-waltz Eiko & Koma perform to the Beatles’ “I am the Walrus,” with a feeling of intensity and microcontrol. More than anything, Eiko & Koma’s masterful stillness, their commitment to “doing nothing” onstage, grabbed audiences’ attention and immediately characterized their work for critics.

The dancers, once sped up to a recognizable pace, neutralize Kaneko’s poetic distaste for the seals with a bodily exploration of seal free time. What might they do during their “big holiday”? (See figure 2.1.) Koma spends his solo recreative seal time fully exploring the stage space. Everything he does is bigger and more accelerated than anything he has done before. He propels himself into the air and falls loudly, only to spiral immediately back up to standing. He circles the stage, a full-legged walk developing into deep lunges, his arms held above his head in an overcurve that seems to extend his trunk upward. He sinks to the ground. Jumps. Collapses into the floor. This time as he tries to rise back up, everything is superheavy: legs, torso, all of it. I am the walrus GOO GOO GOO JOOB, indeed.

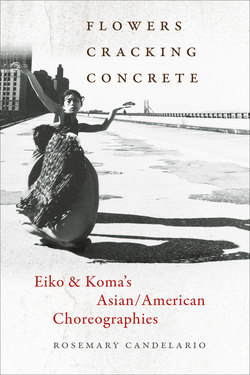

FIGURE 2.1 Flyer for 1977 concert at Theater of Man, San Francisco.Courtesy of Eiko & Koma.

When late in the piece, Eiko reenters the stage wearing a furry shift, Koma skitters toward her and past her off stage. Her seal playtime is taken up with light, controlled, almost waltzy steps. If Koma’s games were big and heavy, Eiko’s are full of suspension and extension. She bounces and then twists slowly forward. Whooooooo! She waltzes with herself and then arrests her momentum. Ending eventually at the bare trunk, she is rejoined by a now fur-clad Koma, a big flower stuck behind his ear. The absurdity begins to build. They both assume positions around the hanging trunk, feet wide and knees deeply bent. As they begin to locomote from this position, weight shifting side to side, their trunks feel heavy, as if they have to grunt with exertion each time they lift a leg. Coming back to the tree trunk, Eiko beats it rhythmically and ritually first with one bent arm, then the next. Finally, they come together in an awkward embrace that appears frequently in their body of work, arms over each other’s backs, rocking back and forth from one side to another. Ho ho ho, he he he, ha ha ha! Eiko jumps on Koma, her legs around his neck, and flips back over. As he drags her across the stage, she spits a flower, Koma’s erstwhile hair ornament, from her mouth. These expert texpert choking smokers stomp around the stage, arms bent at elbows, upper arms level with shoulders, lower arms pointing straight up. They hiss. They shout. They stagger. They bow. It’s over.

Whereas the 1984 media dance based on Fur Seal, Wallow, attempts a more thorough, and sober, embodiment of seals, the 1977 dance makes no claim to verisimilitude, favoring instead a postmodern collage sensibility.14 Whale sounds, a popular song ostensibly about a walrus, a poem about fur seals, harbor seal behavior, a tree trunk—all of these are equally valued in the dance, no matter their actual relevance to fur seals. The black satin costumes worn for most of the piece make the dancers look human, though ironically their movement is more seal-like while in the satin costumes and more human-like in the fur ones. Nonetheless, the human-animal morphing ventured in this dance is an important initial experiment that later became a hallmark of Eiko & Koma’s work.

Not all reviewers embraced Eiko & Koma’s second work. One review (“‘Fur Seal’ boring, but intriguing”) goes so far as to suggest that adding video of actual fur seals to the performance would help audiences understand the dance better and would go a long way to prevent people walking out of the performance, as the author witnessed. The author clarifies the problem as one of unfamiliarity: “Avant garde dancers with their roots in the traditional Japanese style, the two are not only presenting a subject that is basically alien to American audiences, but using an alien theatrical language as well.”15 For others, this “alienness” elicited an Orientalist deference, if not understanding; it was a performance, as one reviewer put it, “to respect and in some ways to enjoy for its originality and sense of integrity.”16 This sentiment calls to mind Bonnie Sue Stein’s later writing about butoh: “The work of these Japanese artists is so thorough and so ‘Japanese’ that Westerners sense a searing honesty…. [S]pectators who may not like it … still respect the experimentation and the performance skills required.”17 Couched in these remarks by both authors is an assumption that one cannot understand the performance because it, like the performers themselves, is so “other.” It is assumed to be incomprehensible, but still has something to admire. While this Orientalist response to the work was not the attitude of the majority of critics, it did represent a growing trend, one I track through this chapter and examine in detail in chapter 3. By and large, however, critical response to Fur Seal was overwhelmingly positive, and Eiko & Koma were welcomed into the New York dance scene as singular avant-garde artists. Anna Kisselgoff, for example, wrote, “At root, their method is as old as Aesop. But their message has the same resonance of post-Sartre and post-Beckett drama.”18 Their next work mined precisely this tension between fable and postmodern performance.

Before the Cock Crows

Eiko & Koma’s first dance created entirely in the United States, Before the Cock Crows, Thou Shalt Deny Me Thrice, premiered at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in summer 1978.19 As the name suggests, the sixty-minute dance tells a story of betrayal, though it has perhaps more resonance with Delilah’s Old Testament seduction and betrayal of Samson than with Peter’s New Testament fear-based denial.20 Featuring the most specific story line of all Eiko & Koma’s dances, Before the Cock Crows is also the most specifically gendered. Eiko owns the birch-branch-delimited stage, spiraling and snaking seductively past Koma before shooting him in the back with her childhood playtime finger guns. Immediately remorseful, she mourns excessively even as Koma comes back to life. Abruptly, Eiko becomes a chicken herself, the cock that has crowed throughout the dance, pecking and scratching, oblivious to the preceding events or the spellbound audience watching her. Accompanied by a Romanian folk song, music by “Belly Dance King” George Abdo and his Flames of Araby Orchestra, and rooster sounds, the dance ends with Koma sinking beneath the weight of a birch branch contraption borne on his back—part oversized crown, part cross—as Eiko herself (no longer a chicken) is bowed by the weight of her own actions. Unlike their two previous works, in this dance it is eminently clear that Eiko & Koma are humans playing characters, at least until Eiko becomes a chicken.21 Seen retrospectively in the context of Eiko & Koma’s larger body of work, Before the Cock Crows is an early iteration of the pair’s oft-repeated mating ritual and a precursor of their attention to cycles of mass violence in the most intimate of settings, a theme explored in detail in chapter 5. For critics, this dance also opened up the possibility of comparing and contrasting Eiko & Koma’s work with modern and postmodern dances.

Like Fur Seal, Before the Cock Crows opens with a period of extended stillness, which had by that point become a marker of Eiko & Koma’s dances in the United States. Although reviews and video documentation reveal distinct variations in the opening22—sometimes Eiko is onstage braiding her hair when the audience enters, sometimes both are there when the lights come up, sometimes Koma comes crashing in later—the lack of discernible movement remains a constant. A cock crows. For minutes, a pulsing track with Middle Eastern instrumentation, perhaps meant to evoke biblical lands, fills the space. The dancers do not respond; impassive, Eiko kneels upstage center while Koma stands downstage right, his left arm raised. They are both draped in folds of material: she in red, he in tan. The stage is inexplicably outlined with long, thin birch branches. By the time the music ends, Eiko has microscopically shifted her head forward, her torso twisting ever so slightly in response. In silence and decreasing light, Koma raises his head and lets his hand descend slowly to his side. This seems to be a signal to speed up to a tortoise-like pace. The protracted openings for which Eiko & Koma were becoming known seemed designed to grab the audience’s attention and keep them there, holding their breath (a number of reviews use this as metaphor), until they are absolutely sure that the audience is with them, at which point they slowly begin to unfold their movement. The dancers recognized the necessity of shifting their audience into an alternate time space and rooting them there for the duration of the piece.

While today that same stillness, combined with layered images and curious juxtapositions, might be seen as butoh or butoh-like, it is important to remember that butoh was not yet known in the United States and was only just being introduced to France. Moreover, Eiko & Koma have never used that term for their work. Instead, at the time Eiko & Koma were embraced and understood as avant-garde or postmodern. Shoko Letton sees a connection between Eiko & Koma’s movement style and American postmodern dance, which she identifies as “a minimalist philosophy of simple means, repetitions, everyday movements and objects, and the manipulation of time.”23 At the same time, Letton continues, “Eiko and Koma’s slowness was considered to be a part of their cultural performative tradition.”24 In other words, audiences assumed that what they were seeing was in some way inherently and traditionally Japanese because the dancers themselves were Japanese. Just enough information about Japanese arts and practices had circulated popularly in the United States that audiences felt they could identify things like Zen and noh in Eiko & Koma’s dances, even though the dancers had little experience with either.

In fact what Eiko & Koma were doing at the time was actively exploring and absorbing new influences. For example, Eiko took belly-dancing lessons while they were making Before the Cock Crows; that experience is particularly evident in the dance’s Middle Eastern sound track and in a solo watched by Koma and the audience alike. Eiko’s willowy arms slowly wave above her head like two snakes, only they are the ones doing the charming. As her hips swivel, taking their time, her dress emphasizes the spirals in her body. Her gaze appears internal, but she keeps her body facing the audience and occasionally even glances its way as her arms and torso continue their side-to-side body waves. Employing the arched back, cocked hip, and spirals of belly dancing, she seduces the audience and Koma both without ever exposing her belly.

While Eiko holds down the center of the stage with her serpent-like arms and torso, Koma circles and criss-crosses the stage, drawn to her, but also trying to draw some attention of his own. Despite largely appearing to be in their own worlds—each with his or her own movement vocabulary and swaths of stage space—the two dancers are clearly, though inexplicably, drawn to one another. They follow each other, approach and then retreat. After one such retreat Eiko hides her face and turns her back to Koma, yet a slight turn of her head indicates that she is still paying close attention. Is she being coy, drawing him in? In other dances in which the pair less clearly represents human characters, this choreographic pattern is described as a mating ritual. Here it is better described as seduction, with Eiko clearly seducing Koma, and the audience in the process (see figure 2.2).