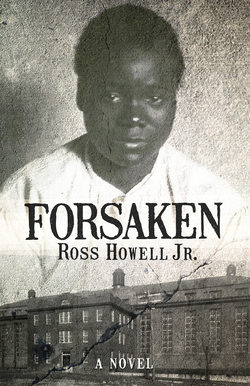

Читать книгу Forsaken - Ross Howell - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3.

Inquest

The night of the Belote murder Dr. Vanderslice swore in five men for the coroner’s inquest. They had inspected the crime scene at the crack of dawn Tuesday morning and were drinking coffee in Sheriff Curtis’ office when I opened the door. The sheriff had his boots up on the fender of the wood stove in the middle of the room. The heat felt good.

“You’re getting an early start, Charlie,” Dr. Vanderslice said. He was standing by the stove, warming his hands. “Come in and have a cup of coffee.”

The sheriff sat up and pulled a chair away from the wall. “Chilly out there, ain’t it, son?” Dr. Vanderslice handed me an enamel cup and a plaid cloth. I picked up the handle of the pot on the stove with the cloth and poured some coffee.

“Thank you,” I said.

“Sit down,” Sheriff Curtis said. I pulled the chair close to the stove.

“You’re the first one in,” Dr. Vanderslice said. He removed a folded document from his breast pocket and handed it to me. “I expect you’ll be wanting to read this. Today we’re interviewing more witnesses for the record.” He nodded. “Go ahead.”

I unfolded the paper.

Virginia, County of Elizabeth City, To wit: An inquisition taken at the residence of Mrs. Ida V. Belote, 809 Washington Street, Hampton, Virginia and continued at the jail office in the County of Elizabeth City on the 18th day of March, continued March 19th, 1912, before G. K. Vanderslice, MD, a coroner of the said county, upon the view of the body of Mrs. Ida V. Belote there lying dead. The jurors, sworn to inquire how, when, and by what means the said Mrs. Ida V. Belote came to her death upon their oaths, do say: said Mrs. Ida V. Belote came to her death on March 18th, 1912, from injuries, wounds and strangulation, received at the hands of Virginia Christian, a deliberate murder. In testimony whereof the said coroner and jurors have hereto set their hands.

“First-degree?” I asked.

“That’ll be up to the Commonwealth’s attorney, but the constable discovered the victim’s purse on the girl’s person after she was arrested. Apparent motive is robbery. Appears the girl was lying in wait for the widow. I don’t see any way around it, do you, Sheriff?” Dr. Vanderslice said. Sheriff Curtis shook his head.

“Especially when you take into account the violence of the act. And the fact that the victim’s children discovered her corpse,” Dr. Vanderslice said. “This’ll be your first murder trial, won’t it, Charlie?” He sipped at his coffee, then brushed the tips of his moustache with the back of his forefinger.

“Yes, sir.”

“Young fellow over at the Daily Press is about the only other one paying much attention right now,” one of the jurors said. I took out my pencil and pad.

“Let me go ahead and get the jury names from this, Dr. V.”

“Certainly.”

I noted the names from the report and refolded it. Dr. Vanderslice put it back in his pocket.

“About that scarf at Mrs. Belote’s neck in the posted statement,” he said.

“Yes, sir?”

“Mrs. Belote took in a boarder a few months after her husband died, to help with the bills, I expect. Fellow’s name is Cahill. We interviewed him. Took work at the shipyard after he left the navy. The Mrs. and the girls liked to wear his uniform blouse and scarf around the house. Seems like a nice enough fellow. Says he overheard the Mrs. giving the colored girl the what-for over something had gone missing. Said the Mrs. could lay it on pretty hot when she wanted to. Bet that little woman didn’t weigh ninety pounds.”

“Ever want you a jar full of piss and vinegar, just find you a small woman of a certain age, ain’t that right, V?” Sheriff Curtis said. Dr. Vanderslice smiled and nodded.

“Thank you, sir,” I said. “I’ll follow up on that.”

“I’m sure you’ll do a good job, son.”

“Sheriff Curtis, would it be all right if I saw the prisoner?” I set my cup on the floor by the stove.

“Sure, head on back, Charlie.” He stood and picked up the keys hanging next to the lock of the steel door leading back to the jail. He unlocked the door and swung it open.

“I expect she’s about finished her breakfast,” he said.

The floor of the jail was stone and the air was cold. Virginia Christian sat huddled in a blanket on a spring cot behind the bars of her cell. Her eyes were open, downcast. She sat so still I didn’t think she had heard me enter. She was staring at the stone wall beyond the bars. I cleared my throat.

“Virginia Christian?”

She raised her eyes. The dim light obscured her face. I could not make out the features. “Daddy gone come, fetch me out of here?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I don’t think so. My name’s Charlie Mears.”

“Why ain’t my daddy gone come?” She blinked once and leaned forward. I could see her cheek now. Her hair was flattened on one side from lying on the cot. On the floor by the cot was a tray and cup. Nothing on the tray had been touched.

“Well,” I said. “Mrs. Belote is dead.”

“Humph,” she said. She put her hand to her cheek. It glistened in the light. She shook her head slowly. “I knowed I never should gone back. I told my momma so, too.”

“It’s best not to talk,” I said. “Not to anybody but your lawyer.”

“I ain’t been in jail before,” she said. “I ain’t got no lawyer.”

“Your father’s getting you one,” I said.

“How come you know so much?” she said. “Maybe I ought not talk to you neither.”

“I work at the newspaper, I reckon is how I know.”

She studied my face. “You ain’t nothing but a boy,” she said. “I can tell a white boy’s age, good as I can tell a colored’s. Bet you eighteen years old.”

“That’s right,” I said.

“Told you,” she said.

“Well,” I said, “I’d better get back out front.” She sprang up and put a hand on the bars. The coils on the cot hummed.

“You see my daddy, you tell him come fetch me. I’m lonesome. Momma don’t like it when I ain’t home.”

“If I do see your father, I’ll tell him. I promise.”

She raised her other hand to the bars.

“What you say your name is?”

“Charlie.” I heard keys jangling.

“Charlie?” Sheriff Curtis called. “Come on out. Couple reporters heading up the street. They better not see, cause I ain’t gone let them back there with the girl.”

“They calls me Virgie,” she said.

I heard the tumblers turn in the lock. “Charlie, you coming?” Sheriff Curtis called.

As the sheriff locked the jail door behind me, Constable J. D. Hicks came in the front door of the office. He was a big man with thick hands. The constable guarded the jail and served as bailiff during court sessions.

“Dr. V expects to call about a dozen witnesses,” Sheriff Curtis said. “Let’s move this table over.” The sheriff and the constable moved a long table from against the wall out to the middle of the office.

“I’ll fetch some chairs from the courthouse,” Constable Hicks said. “Boys, do you mind?”

The five jurors followed the constable out the door. Newsmen started to file in.

“You fellers wait till we get things set up,” the sheriff said. “Space is tight. Gone have to stand in the back, anyway.”

I stepped outside with the others and lit a cigarette.

“Getting a poker game up this evening, Charlie,” Pace said. “You interested?”

An older reporter next to Pace chuckled.

“Oh, that’s right,” Pace said. “That’d be against your high morals, wouldn’t it, Charlie? Coroner ain’t giving you any preferential treatment, is he? You being his pious little college boy and all?”

I could feel my face reddening. I held the cigarette in my lips and pulled out my handkerchief. I wiped my glasses and wrapped the frames back behind my ears. I saw the jurors coming out of the courthouse, each man carrying a chair under each arm. I trotted across the square into the courthouse and picked up a couple of chairs, too. Pace and the other newsmen followed. They each grabbed chairs. I held the door for Pace and the constable.

“That ought to do it, Charlie,” the constable said. “Just pull that door to.”

Witnesses began to arrive about 9:30. Poindexter was among the first to show up. He looked nervous. The sheriff offered him a chair but Poindexter refused and paced the back of the room. I smiled at him when he looked my way but he did not smile back. He had worn a big winter coat and he did not remove it, even though the room was warm. Sweat glistened on his forehead. Finally the sheriff had enough and told him to sit down. Poindexter complied. Then he stood up again, shucked off the big coat, and sat back down, piling the coat on his lap.

Dr. Vanderslice greeted the witnesses as they entered and showed each one to a seat. I recognized Mrs. Stewart, who lived upstairs at the C&O depot with her husband, Gus, the station manager. Other women I remembered seeing standing in front of the victim’s house came in. The only person of color who entered was a woman wearing an apron and bandanna. A trim man with wavy brown hair and a thick moustache entered. Dr. Vanderslice nodded to him as he took a seat. The constable opened the stove firebox and jabbed at the coals with a poker. He added an armload of wood, shut the firebox, and turned down the draft. Then a small, pale woman entered the jail, the girl I recognized as Harriet flanking her on one side, and the younger girl, Sadie, on the other. Everyone in the office stood, some leaning one way or the other to get a view. These were Mrs. Belote’s three daughters. Dr. Vanderslice took the woman’s hand in both his for a moment and bent to speak to her. She pressed a white kerchief to her cheek. Dr. Vanderslice touched Harriet on the shoulder, Sadie on the head, then guided the three to their chairs with the other witnesses. Sheriff Curtis unlocked the iron door and went back in the jail. He returned with Virginia Christian. She stood, the sheriff holding an arm, by the door.

“Hello, Virgie,” the little girl called from her chair.

The black girl smiled faintly and lowered her eyes.

Dr. Vanderslice beckoned the jurors, who took their seats behind the table. He immediately seated himself with them.

“Coroner’s inquest, Virginia, County of Elizabeth City, here continued. I now call Miss Harriet Belote,” he said.

When the girl stood, she wavered, and her older sister reached for her hand and held it a moment. The girl’s black hair hung in a long braid down her back. Pace leaned forward. The room was silent, save for the crackling of the new wood in the fire and the wind sighing in the flue. The girl stepped forward and sat in the chair, erect, not touching the chair back.

“Harriet Belote, you told me you went to school yesterday?” Dr. Vanderslice asked.

“Yes, sir, I did.”

“About what time did you leave home for school?”

“About a quarter after eight.”

“Was everything all right when you left for school?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Mr. Cahill, who boards at your house, had he gone to work?”

“Yes, sir.”

“When you returned from school, was everything all right?”

“Everything was quiet. My little sister was out playing. I thought my mother was out.”

She sat perfectly still, her back to us. Her voice was calm and musical, like the middle range of a piano. Dr. Vanderslice and the jurors never took their eyes from her face.

“Did you see anything unusual when you went in the kitchen yesterday?” Dr. Vanderslice asked.

“I noticed the bloody water in the basin.”

“When you saw the bloody water what did you do, did you go in the room?”

“I looked at it and then started in the front room to get my lessons and something told me not to go into the room; I saw my mother’s hair and combs lying on the floor, and I called my sister.”

“Did you see any blood on the floor?”

“I saw two little splotches; I did not go into the room where it was.”

“Why didn’t you go into the room?”

“My heart just failed me, that’s all.”

“Where did you go then?”

“I ran out and called the Warriner and Richardson boys and told them to go in there.”

“What did they do?”

“They went in there and saw the blood and they were frightened too, and they went down to the depot and called two men.”

“What two men did they call?”

“Gus Stewart and another man. They work at the depot.”

“You stated that your mother was all right when you left home that morning. Had your mother had any difficulty of any character, or any kind, at any time?”

“I know about the skirt.”

“Well, what about that?”

“Sunday a week ago when my mother was getting ready to go over to my married sister’s in Newport News, she missed her best black skirt.”

“Had you missed any sort of articles before?”

“A gold cross and chain of mine, but I got that back, and another time a ring that was missing and she looked around and found it behind some things. And Momma missed a light apron and my little sister missed her gloves, and once a locket. Momma did not say anything about these but she said that she could not afford to lose a skirt.”

“And Virgie once quit washing for your mother?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Did your mother discharge her when she quit washing that time?”

“No, sir, she didn’t discharge her. She stopped on her own accord, she said her mother was paralyzed, and she said she could not wash any longer.”

“You always found her amicable, and of a pleasant disposition?”

“Yes, sir, she seemed to be pleasant; we did not miss anything the first time she washed for us, not a thing.”

“Thank you, Miss Harriet; I have no further questions for you.”

She stood and faced us, pale and rigid. I heard Pace breathe next to me and realized I had been holding my breath, too. She glanced quickly at Virginia Christian and sat down.

“I now call Miss Sadie Belote,” Dr. Vanderslice said.

The girl popped from her chair like a jack-in-the-box and stepped lightly toward the table. Dr. Vanderslice chuckled and gestured toward the chair. She sat, looked once over her shoulder at the small woman, her sister, who nodded, and then back at the coroner.

“How old are you?” he asked.

“Eight years old.”

“You know how to tell the truth, don’t you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And you know what will happen if you don’t tell it?”

“Yes, sir,” the girl said, nodding solemnly. “Momma will tan my hide.”

Dr. Vanderslice touched his moustache, hiding his reaction. A juror smiled, remembered himself, and coughed into his hand.

“And you will tell me the truth about everything I ask you, won’t you?” Dr. Vanderslice asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“Who is your mother?”

“Mrs. Belote.”

“Mrs. Ida Belote?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And Harriet Belote is your sister?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Did you go to school yesterday?”

“Yes, sir.”

“About what time did you get out of school?”

“A little after twelve.”

“What did you do?”

“I went in the front room, put my books away, and called Momma.”

“Did she answer?”

“No, sir.”

“What did you then do?”

“I went next door to Mrs. Guy’s looking for Momma.”

“Was she there?”

“No, sir, Mrs. Guy served me dinner.”

“After dinner what did you do?”

“I went to play with the neighbor boys until my big sister got home.”

“Who does the washing for your mother?”

“Virgie.”

“Virgie Christian?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Did you see her yesterday?”

“I saw her standing on the corner when I was leaving school.”

“Did you speak to her?”

“No, sir, I was on the other side of the street when she called me.”

“What did she say to you?”

“She told me to tell Momma that she can’t come to wash today.”

“Were you home when your mother missed her skirt?”

“Yes, sir.”

“What happened then?”

“Momma sent me to fetch Virgie.”

“Did Virgie agree to pay for the missing skirt?”

“Yes, sir. She said that she didn’t have the skirt.”

“Did Virgie quarrel with your mother?”

“No, sir.”

“Thank you, Miss Sadie; I have no further questions for you. I now call Mrs. Pauline Wright.”

The small woman stood. She helped Sadie take her seat next to Harriet, then sat in the witness chair.

“Mrs. Wright, have you heard your mother speak of losing a skirt?” Dr. Vanderslice asked.

“Yes, Momma was up to my house Sunday a week ago. She sent for Virgie about it.”

“What did Virgie say about the skirt?”

“She promised to pay five dollars for it, but said she didn’t have the skirt.”

“Did your mother and Virgie quarrel over the lost skirt?”

“No, sir, when Virgie was called, she looked scared.”

“Were you at your mother’s last Sunday?”

“Yes, I was. Momma said she hoped Virgie would come tomorrow and pay for the skirt. If she didn’t, she’d make trouble for her.”

“Was the relationship between the woman and your mother pleasant?”

“So far as I know.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Wright. I have no further questions. You and your sisters are free to go. There’s no reason for us to keep you here.” Dr. Vanderslice and the jurors stood as Mrs. Wright helped Sadie with her coat. It was easy to read the sadness written in her face and Harriet’s. Virginia Christian kept her eyes lowered until the sisters left and the constable closed the front door behind them. The colored girl raised her eyes and looked at the door for a long time.

“I now call Mrs. Mary Stewart,” Dr. Vanderslice said, taking his seat.

Mrs. Stewart, the wife of the C&O depot manager, testified to observing the comings and goings of Virginia Christian, Mrs. Ida Belote, and the girls, as did other witnesses. There were differing descriptions of the colored girl’s dress and manner, whether she appeared agitated or calm, whether she was walking or running, but the testimony showed that she had in fact entered and left the house the day of the murder. Also called to testify was the black woman in the apron. She was Lucy White, who cooked for one of Mrs. Belote’s neighbors. She also testified to seeing Virginia Christian enter the Belote house on the day of the murder.

“I now call Mr. Joseph Timothy Cahill to the stand,” Dr. Vanderslice said. The trim young man with the bushy moustache stood and approached the inquest table. His gait was lithe and agile. He took the seat.

“Mr. Cahill, how long have you boarded at Mrs. Belote’s?” Dr. Vanderslice asked.

“Since November of last year.”

“About what time did you leave for work on yesterday morning?”

“About six to seven minutes after 6:00 a.m.”

“Do you know of any problem that Mrs. Belote had with a servant?”

“Yes, she had a little argument about a skirt.”

“What about the skirt?”

“I was there when she missed her skirt. She sent her little girl around for her. Mrs. Belote told her she wanted the skirt or five dollars. The girl seemed very cool.”

“Was Mrs. Belote angry?”

“Yes, she was a woman of stern mind.”

“Was Mrs. Belote abusive to her?”

“No, sir, just stern.”

“How much do you pay for board at Mrs. Belote’s?”

“Five dollars per week.”

“When do you pay for board?”

“Each Saturday evening.”

“How do you pay?”

“In cash, five one-dollar bills.”

“What did she do with the money?”

“She would put it in her small change purse.”

“Would you know this purse when you see it?”

“I think so.”

“Was it like this?” Dr. Vanderslice held up a small, gray, leather purse.

“Yes, sir, that’s it.”

“Mr. Cahill, do you at any time wear your Navy uniform blouse?”

“No, I wear overalls.”

“Would the young ladies there ever wear your uniform blouse with your name on it?”

“Yes, they would from time to time.”

“Would they wear your neck kerchief?”

“Yes, they would.”

“I have no further questions of you. I now call Mr. Poindexter.”

Cahill nodded to Dr. Vanderslice and the jurors and walked back to his chair among the witnesses. Poindexter’s big coat flopped on the floor when he stood, and a woman sitting next to him helped him arrange it on his seat. He stepped quickly to the witness chair.

“Mr. Poindexter, you are employed at the C&O depot?” Dr. Vanderslice asked.

“Yes, sir, I am a telegraph operator.”

“Were you working yesterday?”

“Yes, I was.”

“Do you know Mrs. Ida Belote when you see her?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Did you see her yesterday?”

“No, I didn’t see her yesterday.”

“Do you know this girl who works for Mrs. Belote?” Dr. Vanderslice pointed to Virginia Christian. She raised her head and looked at Dr. Vanderslice, then up into the face of Sheriff Curtis, then down at the floor. Poindexter cleared his throat.

“Yes, I know her.”

“Did you see her yesterday?”

“No, I did not.”

Dr. Vanderslice furrowed his eyebrows and leaned forward. “Mr. Poindexter, when was the last time you saw her?”

“Oh, yes, it was yesterday, yesterday between 9:30 a.m. and 10:30 a.m.” Poindexter cast a glance at Virginia Christian. He turned to the jurors and smiled nervously.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I get the fantods talking in front of people. I’m not used to it. I’m used to somebody handing me a slip of paper, I type in the message, give them the bill. That’s what I’m used to.”

“That’s all right, Mr. Poindexter. Take your time. How was she dressed when you saw her?” Dr. Vanderslice asked.

“As well as I can remember, she had on a black skirt with I think a hole on the right side about a foot from the ground.”

“Were you looking out the office window?”

“No, I was at the office door. I didn’t notice the color of her shirtwaist.”

“Was she wearing a hat?”

“No, I didn’t see a hat.”

“Did you speak with Virginia Christian?”

“No, she was not within one hundred yards of me.”

“Thank you, Mr. Poindexter; I have nothing further. I now call Constable J. D. Hicks.”

Poindexter pulled a handkerchief from his hip pocket and wiped his brow. Now that he was leaving center stage, he looked relaxed, like a boy leaving the proctor’s office. He retook his seat among the witnesses.

Constable Hicks lumbered toward the witness chair. He was holding something with the big fingers of one hand. He had slicked his hair down with pomade. When he sat in front of the jurors, he looked like a man in a child’s parlor chair.

“Constable Hicks, tell us what you know about this case?” Dr. Vanderslice asked.

“Virginia Christian was brought here yesterday. She was searched and turned in a small change purse. I asked her did she have anything else. She said no. I had her take off her shoes. I ran my hand around in her stockings looking for a knife. I told the sheriff that I had searched her. He instructed me to go back and give her another overhauling.” Despite his bulk Constable Hicks had a high voice, near tenor in pitch. His features were heavy but he had a kind face.

“Did you give her an overhauling?”

“Yes, sir. I went back up and brought her out of her cell. ‘Virgie,’ I said, ‘have you got anything on you?’ She said, ‘No, sir.’ I then asked her when was the last time she had her monthly? She said, ‘Yesterday. I’ve finished with them.’ Sheriff R. K. Curtis came in. I then made Virginia Christian disrobe and I found on her sleeve, a good-size bloodstain. I then asked her if she had any more bloodstains on her. She said, ‘No.’ I found under her left arm a bloodstain. I asked her to explain this stain. She said her mother had a hemorrhage and she reached across to give her something to wipe with. A drop of blood must have gone through. I instructed her then and there to pull everything off. I found bloodstains on this garment.”

He held up what looked to be an article of women’s underclothing.

“I found this instrument strapped around her waist; in it was a purse.”

He held up a pouch, maybe made of canvas. The chair creaked when he leaned forward and handed the articles to Dr. Vanderslice.

“Constable Hicks, you say you found this thing tied around Virginia Christian’s waist?” Dr. Vanderslice held up the pouch for the jurors to see. “And in it was a purse?”

“Yes, sir. It contained four one-dollar bills and a gold ring.”

“Did you ask Virginia Christian about the purse?”

“Yes, she said the purse belonged to her mother and she was keeping it for her.”

“How was this thing strapped to her body?” Dr. Vanderslice placed the pouch on the table beside the undergarment.

“It was strapped right next to her drawers,” Constable Hicks said. He looked sheepishly at the coroner and the jurors. “The sheriff then sent around to her parents’ and got a new set.”

“Would you know the purse found on her?”

“I think so.”

“Is this the purse?” Dr. Vanderslice held up the item he had shown Cahill.

“That’s the purse, all right.”

“Was she told for what she was arrested?”

“I think not.”

“Did she volunteer any information to you about Mrs. Belote?”

“No, sir. She said that she had been washing all day.”

“Where did you say you found the instrument or bag?”

“It was tied around her waist, tied with a necktie and string.”

“Thank you. I have no further questions of you, sir.” Again the chair creaked as Constable Hicks stood.

“I would like to thank all of those who testified today in this matter,” Dr. Vanderslice said. “The inquest is now closed.”

I looked to see the sheriff turn Virginia Christian toward her cell.

Witnesses had seen her enter the Belote house. Testimony established robbery as a motive. In custody she had lied to authorities and concealed evidence. Murder in the first degree. I burst out the front door of the sheriff’s office, with Pace right behind. He easily outran me, heading in the direction of the Daily Press offices. At the corner I stopped and lit a cigarette. Everything pointed to the girl, but I wanted to ease my mind about the boarder. Tomorrow I’d see if I could find Cahill’s employer.

The air had hardly warmed since morning. I set out for the office, wishing I had worn a scarf.