Читать книгу Forsaken - Ross Howell - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2.

Black Woman Held

Poindexter was a good man to talk to. He was the telegraph operator at the C&O depot. Say he helped somebody with a message, or noticed somebody come into town on the afternoon train, or overheard somebody talking on the platform—Poindexter would let you know if something was up.

Late afternoon March 18, 1912, I was heading for the depot. It was a Monday and all the news was from the mountains. The wires were humming with stories about the Allen gang. They’d killed a sitting judge, Commonwealth’s attorney, sheriff, and a witness up at the Hillsville courthouse. Wanted posters were tacked up at the depot and the sheriff’s office. The governor had called Baldwin-Felts detectives into Hillsville. They were manhunters. I thought I’d have a smoke with Poindexter, see if he’d heard anything, and walk back to the office.

A colored boy ran by me like the brick sidewalk was burning coals, grabbed an iron gate to stop himself at a stoop, and hollered up the steps.

“Jeff, come quick! Woman got killed over on Washington. Best come on, you want to see it!” Another boy dashed out the door and down the steps. The two of them ran up the street.

I set off at a trot and saw the two boys turn the corner. A little over a block away, white and colored people were congregating. The address was 809 Washington Street. There was a trellis gate with climbing roses starting to bud. Standing just outside a group of colored women on the walk was a tall white man in a bowler. He was chewing a cigar stub.

“Sir, what happened here?”

“Widow woman got killed. Say her washwoman done it. Somebody at the C&O seen the girl coming and going from the house.”

About fifty feet down the street was a sleek chestnut mare hooked to a buggy. I recognized her. She nibbled at a patch of new grass at the edge of a yard. One of the buggy wheels was up on the curb.

A tall man with thick brown hair parted in the middle and a Vandyke emerged from the house, heading for the street. He was carrying a small black bag. That was Dr. George Vanderslice, coroner for the city of Hampton, the owner of the mare. He walked to the trellis gate and stopped, casting his eyes about until he saw the buggy.

“Phoebe!” he called. The mare lifted her head and nickered, but didn’t move. He opened the gate and started toward the buggy. The people on the sidewalk made a little room for him, but they still blocked my way.

“Dr. Vanderslice!” I shouted. “Can you give me any information?”

“Go to the sheriff’s office, Charlie. Get a statement there.”

“Has there been a homicide?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “Go to the sheriff’s.”

“Who was the victim, Dr. Vanderslice? Was it a woman?”

“Mrs. Ida Belote, a widow,” he said. “Now get going!”

The name was painted on the mailbox. I made a note of the spelling. The house stood a hundred yards from the C&O depot. I headed down Washington Street at a sprint. Sure enough, Poindexter was on the platform. His cap was askew and his eyes glistened with excitement.

“Did they tell you I seen the colored girl, Charlie, the one does the washing for the widow woman? Seen her walking fast toward Sam Howard’s store about 11 o’clock this morning. Why I reckon this is the biggest thing ever happened in my life.”

“No,” I said. “I’ll have to get your statement.”

“Couple guys loafing on the mail carts this afternoon heard some boys hollering and said there must be trouble.” He whistled. “This sure beats it, don’t it? Neighbor lady brought the girls in.”

“What girls?”

“The widow woman’s girls. Two of them. They’re sitting in there right now.”

I pushed open the swinging doors into the depot. The sun hung just above the rooftops and the air was getting chill. It swirled at my ankles as the doors shut behind me. A woman I would guess to be in her fifties was sitting on the bench. She was wearing a straw bonnet, the kind you’d expect to see in summer. It sat too far back on her head and the ribbon was untied. A pale, thin girl was leaning her head on the woman’s shoulder, and a younger girl was leaning hers on the pale girl’s. The younger girl had a pink peppermint stick in her mouth.

The woman on the bench sat forward when she saw two sheriff’s officers approaching from the platform. The girls raised their heads. The officer walking in front was a big man with sandy red hair and rosy cheeks. The other officer was smaller, wiry build, brown hair.

“Ma’am, I’m Deputy Leslie Curtis Jr.,” the officer in front said. “This is Officer R. D. Hope. Are these your children?”

“No,” she said. “These are Mrs. Belote’s children. I’m Mrs. Belote’s neighbor. This is her daughter Harriet,” she indicated the pale girl beside her, “and this is her baby girl, Sadie. Sarah Elizabeth.” She patted the knee of the younger girl. Harriet looked pretty calm. Sadie’s eyes and nose were red from crying.

Sadie took the peppermint stick from her mouth. “Is Momma all right?” she asked the deputy. “Did she get hurt?”

“She did, honey,” the deputy said. “We’ll just have to wait and see how bad. Do you girls remember your momma having trouble with anybody?”

“Uh-huh,” Sadie said. “Momma was mad with Virgie about taking her skirt.”

“Who’s Virgie?”

“Virginia Christian,” the older girl Harriet said. “She’s the colored girl who washes clothes for my mother. My mother thought she’d stolen her best black skirt. But we found it.” Harriet’s face hardly moved as she spoke. She sat rigid as a feral cat. Her voice seemed to come from somewhere else. Her eyes looked black as ink.

“Do you know where this colored girl lives?”

“Wine Street,” Harriet said. “Three hundred something.”

“Ma’am, has any family come round?” the deputy asked the woman on the bench.

“Not yet,” the woman said. “The girls have an older sister, Pauline Wright. She was married just this past year. Lives over in Newport News. I’m sure she’ll get here soon as she hears the news. Then there’s Mrs. Belote’s brother in Norfolk, a businessman.”

“I hate him,” Harriet said.

“Goodness!” the woman said. “You shouldn’t speak that way about your uncle.”

“I want Pauline to come,” Harriet said.

The woman nodded and stroked the girl’s hair. “She will, dear. She will.”

“Ma’am, could we ask you to look after the girls, then? Sheriff’s office ain’t really a fit place,” the deputy said.

“Of course,” the woman said.

“Well, R. D.,” the deputy said, “let’s tell Chas about this colored girl.”

“All right, Junior,” the other officer said. They tipped their hats to the woman on the bench. “We’re much obliged, ma’am.”

Passersby had joined the crowd on the street in front of the Belote house. A couple of saddle horses were tied to the fence. A freight wagon was parked in the street. The teamsters were smoking cigarettes with their boots propped up on the rail of the wagon. They were watching a pack of boys roll hoops in the street.

“You men get that rig moving!” the deputy hollered.

“All of you, move on!” the other officer said. No one did, except for the teamsters.

A hearse from Rees’ Funeral Parlor was parked where Dr. Vanderslice’s buggy had been. Two men filed out the back door of the house carrying a litter. A body was bound in a bed sheet. Dark splotches stained the sheet. Some of the women in the crowd gasped and put kerchiefs to their faces.

“Look yonder!” a white boy hollered. “That there’s a corpse!” His hoop banged into the picket fence and a woman shrieked.

“You boys don’t get on, I’ll haul ever one of you to jail,” the deputy said.

The white boy grabbed his hoop and dashed off.

The two officers from the depot entered the rear of the house. I stood outside on the little porch. Inside was Deputy Charles Curtis, the one the officers called “Chas.” I recognized him from a story I’d covered, a domestic disturbance in a Negro house. He was a good investigator.

He looked up from where he was crouched. “Looks like we had us one hell of a catfight in here, boys,” he said as the officers walked in. “Watch, Junior! Don’t touch that wall.” He pointed to a smear of blood at the door frame. Junior snatched his hand back.

“Sorry, Cousin,” he said.

Chas continued to examine something on the floor. He sighed. Then he stood and hooked his thumbs in his holster belt. He was a big man with the same sandy hair and florid complexion as his cousin, but taller. “One of them won’t be caterwauling no more, that’s for sure. You interviewed anybody, Junior?”

“Neighbor lady and two girls over to the C&O,” the deputy said. “The daughters. What they said, reckon we need to hunt up this colored girl on Wine Street does the washing.”

“Girl name of Virgie, right?” Chas asked.

“That’s right.”

Chas rubbed his chin. “Yep, figures. Lady out front lives across the street claims she seen the colored girl leaving in a hurry this morning. Near as we can make out,” he said, tapping a finger on his holster, “the daughters was the first ones in the house this afternoon. Doc V and me talked to them here. The little one’s eight. She come home from school about noon. Walked into the kitchen and called for her momma, got no answer. So she put away her books, she said, and went to Mrs. Guy’s, that’s the neighbor lady next door, to see if her momma was there. Mrs. Guy fixed her something to eat. Then she goes outside to play with some of the neighborhood kids. Then the older daughter shows up. She said she’s thirteen.”

“Looks like a preacher’s wife, don’t she, Chas?”

“Reckon she does, Junior, now you say it. Real stiff-backed. Anyway, she’s the second one in. Gets home from school right after three carrying loaves of bread she bought with the dime her momma give her in the morning. Puts the bread down on a stool in the kitchen. She calls for her momma, too. No answer. Goes to the front room to put away her books. Starts to feel uneasy. By the door she sees her momma’s hair combs on the floor. Figures that’s strange. Some of her momma’s hair’s in the combs, too. Long strands. Then she sees blood drops on the floor.

“So she runs back to the kitchen. Notices more blood drops and bloody water in a basin on the sink. Now she’s good and scared. She runs out the front door to the gate and sees two boys in the street. Asks them will they come in the house and look around. She waits at the gate while the boys go inside.

“Them two boys, that’s numbers three and four. Boys see the blood drops on the floor and get scared, too. So they scurry off to fetch help at the depot, leaving her at the gate. Pair of men on the platform hear the boys hollering, soon as they hear ‘blood,’ they roust the telegraph man Poindexter and tell him to send for the sheriff.”

Chas unhooked his thumbs from the belt. “Junior, I’m gone take R. D. over to Wine Street with me. Can I get you to stay here, keep them people on the street out of the house, messing up the crime scene?”

“That’ll be fine,” the deputy said.

“Awful thing, them girls coming up on their momma like that,” Chas said.

I stepped behind a porch post to make room for the officers to pass. When they were a ways down the sidewalk, I followed. The two colored boys who ran by me earlier fell in behind them. One of the boys hooted. The deputies turned and said something and the boys ran down the sidewalk away from them. The officers got in their car and drove down the street. The boys chased after the car as it turned the corner.

By the time I reached the front gate of 341 Wine Street, Chas and Officer Hope were walking a Negro girl out, one man holding each arm. That was the first time I saw Virginia Christian. She walked between the officers without raising her eyes. She was small, about five feet tall, and sturdy. Her color was very dark. She walked with a heavy stride. At the gate she looked up at each of the colored boys on the sidewalk. Then she looked at me. She looked angry. Then her face turned away. The deputies walked her past us. Chas opened the door to the vehicle. Officer Hope helped her onto the running board and eased her into the back seat. The officers stepped into the car and drove away. I shouted questions as they rode by but they didn’t reply.

One of the colored boys whistled.

“You see that, Jeff? She stared her a hole plumb through us. Like she gone murder us, too.”

“Hot dang!” the other boy said. “We got us our own murderer, right on this street.”

A colored man came out of the house and started down the sidewalk.

“Sir, what’s happened here?” I asked.

He didn’t answer. He looked about him, befuddled, then turned and walked past the boys. I stepped in front of him.

“Sir, are you any relation to Virgie?”

“She my girl.”

“What is your name, sir?”

“Henry Christian.”

“Did the police arrest your daughter?”

“Yes,” he said. He held a thick piece of paper he kept folding and refolding. His hands were shaking. He placed the paper in the pocket of his coat.

“Did they state the charge, sir?”

“Them deputies didn’t say nothing. Nothing. Here, I got to get by. I got to see Mr. Fields.”

“Thank you, sir,” I said. He continued up the street until he came to the gate for a big clapboard two-story house at 124 Wine Street. A shingle by the gate was painted, “George W. Fields, Esq. Attorney at Law.” I watched Mr. Christian pass through the gate and up the walk. He knocked at the door. When it opened he went inside.

I walked back to the Christian home. Black children were milling about the yard and in the street. I heard a woman sobbing inside the house. Through the front door I could see a colored woman reclined on a pallet. She was a big woman, with light skin. She leaned against thick pillows that held her torso upright.

“Oh, Lord! What they gone do with my Virgie?” she asked. The children in the yard began to wail.

I stuck my pencil and notes in my breast pocket. I wanted to smoke a cigarette. But I started to run as fast as I could toward the sheriff’s office.

A couple of reporters already were there.

“Looks like you been doing some serious bird-dogging and all, Charlie.” It was Charles Pace, my competitor at the Daily Press. Everybody called him Pace. We covered the same beats. I resented him because his instincts for the news were better than mine. He resented me because I’d had it easy, a college snob. He’d first come to Hampton as a bound boy, forced to work his keep on the docks.

My face was flushed from running and my eyeglasses had fogged up. I took a handkerchief from my trousers and wiped the lenses.

Pace was scanning the cork board at the front of the sheriff’s office. I hooked the wire temples over my ears. Pace was tall. Peering around his shoulder, I could make out Dr. Vanderslice’s signature. He must’ve posted the coroner’s report.

“Hey, how about making some room?” I asked.

Pace didn’t move. He made a couple more notes, then caught me with an elbow as he turned. He trotted out the door. I rubbed my ribs and started to read.

The body of the victim, Ida Virginia Belote, was lying face down in a back room on the right-hand side of her house. The deceased appeared to be about 50 years of age. Her upper and lower false teeth were lying on the floor of the room near her body. A bloody towel was rolled and stuffed tightly down her throat, pushing in locks of hair. The towel depressed the deceased’s tongue and inverted her lower lip. She had finger marks and bruises about her neck and beneath her jaw. Her right eye was blackened, and her left eye was swollen shut. Just above the deceased’s left ear was a three-inch long cut down to the bone. The head and face were bloody. At the throat of the deceased was a sailor’s neck cloth. There was a dry abrasion on the elbow of the left arm. There was no visible sign of rape.

In the middle room, near the front door, were shards of brown crockery. A spittoon covered with blood lay on the floor, along with three small black hair combs. On a box behind the door of the middle room were blood stains. There were blood stains on the floor leading to the adjacent back room on the right. Blood stains were on the door facing leading into the room on the right, about two-and-a-half feet from the floor. Under a bureau between the window and door was a pool of blood, and smeared blood and bloody clothing on the floor. A white porcelain jar top was found shattered into many pieces. No money or purse was found.

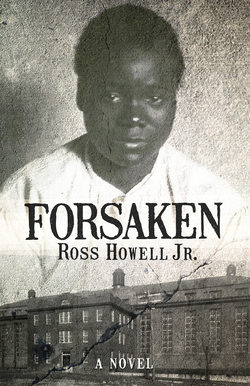

I scribbled notes and ran for the Times-Herald office. I just made the deadline. The front-page headline read, “IDA BELOTE IS BRUTALLY MURDERED, BLACK WOMAN HELD.”

I sat out on the porch of my rooms, smoking. We’d had a shower at nightfall. The wind was raw. I read the story for probably the twentieth time and folded the paper. When the wind stirred, water dripped from the trees onto the roof of the porch. My hands were freezing.

In the morning Tyler Hobgood, the editor at the paper, called me into his office. Mr. Hobgood usually looked like he’d spent the night away from home. When he’d hang his suit coat on the tree, his shirt was always rumpled, the collar askew, and his shirttail poked from the back of his vest.

“These coloreds,” he muttered, and shook his head. “A white woman in her own house.” He looked into my face. I had never noticed how sad his eyes were. His moustache needed a trim. “Stay on this one, Mears,” he said. “Day or two, you might be reporting a lynching.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Whole lot more serious than college, ain’t it?”

“Yes, sir.”

He opened a desk drawer and took out a bottle. He poured a dram of whiskey into his coffee cup. He tilted the bottle toward me.

“Want a little hair of the dog?” he asked.

“No thank you, sir.”

“Still teetotaling?”

“Yes, sir.”

“In this line of work,” he said, “you might want to change that, Mears.”

“Yes, sir.”

He drank down the whiskey and set the cup on his desk.

“Can you spare a cigarette?” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

“Mayor Jones is worried about violence,” he said. “Ordered the coroner to complete the inquest soon as he can. Lucky Strike. Good cigarette, Mears.”

“Thank you, sir.”

He struck a match. “Nobody wants a mob in the streets, Mears. Bad for business.” He lit the cigarette, shook out the match, and blew a puff of smoke. “Anyway, get what you can at that inquest. They’re convening at the sheriff’s office. And don’t forget I need something for the society section on the Ladies’ Club meeting over in Phoebus.”

By the time I made it to the courthouse, Dr. Vanderslice’s mare was nibbling daffodils in front of the Elizabeth City County jail.