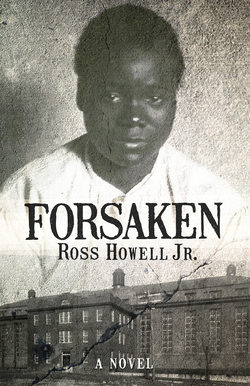

Читать книгу Forsaken - Ross Howell - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление7.

Red

I stared into the darkness where Lucky had vanished. I wanted to help Harriet but I had no idea how. I understood little about intimacy, less about the danger Harriet had described. The men I worked with seemed to be versed in such matters. But their views were coarse.

Did I know how to befriend her? Friendship had been hurtful to me. I had retreated into despair when my friend Fitz died. Loneliness had become my shepherd.

I lit another cigarette and blew out the match, watching white vapor curl from the head. I dropped the match in the cuspidor. The first friendship of my life had been hurtful, too.

Red and I met at school in 1902. He sat on the bench next to me in Miss Quesinberry’s one-room school on Flag Run. His hair was the color of copper wire and his eyes were green. He carried with him a little edition of Aesop’s Fables.

“Mind if I try them spectacles?” he asked. His canvas trousers were patched with a variety of fabrics and held up with a length of sisal.

“No,” I said. “I don’t mind.”

I loosed the wire rims from my ears and handed the glasses to Red.

“Them’s like fish hooks,” he said.

“Put the frame on your nose, then run your fingers round your ears,” I said. “It’s easy.” He hooked the temples over his ears.

“Don’t work worth a damn,” he said. “Everything’s blurry.”

“They have to be made special,” I said. “What’s your name?”

“Red,” he said. “What’s yours?”

“Charles,” I said.

“That your last name?”

“First name.”

“Oh, then you mean Charlie,” he said.

“No, Mother calls me Charles.”

“That ain’t no kind of name.”

“How about Red? That’s not a real name.”

“Course it is.”

“An old man I know has a dog named Red. That can’t be your real name.”

“Why, I reckon it is,” he said.

“Would you boys be so gracious as to share your conversation with the rest of the class?” Miss Quesinberry asked. She stood over us, cradling the handle of a leather strop in her hand. “Franklin! Give Charles his eyeglasses immediately! Go to the bench in the back. I don’t want to hear you two talking anymore today.”

The next day at school when Red slid in on the bench next to me, he sighed.

“Well,” he said. “You heard. Franklin my name. But everybody call me Red. Momma say the day I was born my hair so bright all the people call me that. She say even my skin was red day she showed me to people.”

“That’s all right,” I said. “That’s a nickname. I’d say Red is about as good a nickname as somebody could have.”

“You mind I call you Charlie?” he asked.

“Just don’t do it in front of my mother.”

“They ain’t no danger in that,” he said.

That fall Red and I became friends. Not once do I remember my mother being in earshot of Red, although we often spent time in the company of his. Red lived with his mother, Sarah, in a one-room wooden shack by the railroad tracks just outside Jerusalem. The shack was roofed with tin. Red and I would sit on the little front porch and listen to the rain drum on the tin. Sometimes the wind would blow the rain spilling from the roof onto our faces, and it felt cold as ice. If we had found a toad in the shade under the house, we’d turn it loose and watch it hop down the steps, big drops spattering its back, until it made its way under the house to shelter.

Red’s mother was a tall woman, tall as a man. Her eyes were queer, the eyes of a being who could cast spells over creatures or men. They were large, set far apart, the color of amber. Sometimes she caught me staring at her but she never scolded. She would smile faintly and look away. Her hair was always wrapped in brightly colored scarves, and she would carry water to the house balancing it in big jugs on her head. She was thin, so thin her ebony skin looked drawn over her bones.

“People say she been bony ever since I was born,” Red said. “Course, I ain’t got no way of knowing, cause I flat out don’t remember. People say she got some kind of blood flux. Say that’s why she don’t have no more children than me.”

“Where’s your daddy?” I asked.

“Don’t rightly know,” he said. “Ain’t never seen him. Some people say he got killed. Momma don’t seem to know.”

“People say my daddy was killed, too,” I said. “Out west. By an Irishman.”

“What’s that?”

“A foreigner. They about starved out. So they came here. You can tell them by their red hair.”

“Well, I ain’t no Irishman.”

“Course you’re not. Not everybody has red hair is an Irishman.”

“Humph,” he said. “I’d whole lot rather be a red-headed nigger than some foreigner.”

“Me, too.”

Red’s mother cooked hoecakes right in the coals of the hearth. She grew little green peppers in her garden she would hang from the rafters of the shack in the winter. She seasoned her batter with the peppers and they made your tongue burn and your eyes water. Red loved her hoecakes and I learned to love them, too. One time we tried seeing who could hold one of those dried peppers in his mouth the longest. I spit mine out right off but Red held his until his face turned red and his freckles were black as peppercorns. Tears were running down his cheeks, and still he held the pepper. Then his mother came in and caught us. She laughed out loud when she saw Red’s puckered face. Then she quit laughing and switched Red good.

Sometimes Sarah would sit with us on the porch as we listened to the crickets and katydids. She would smoke a corncob pipe to help drive off the mosquitoes. She stretched her long legs down the steps, and the skin of her legs glistened. One evening a colored girl in a faded dress ambled along the road. She was barefoot, and a strap of her dress had fallen from her shoulder. She paused and plucked a stem of marsh grass and placed it in her teeth. She was older than Red and me, with fascinating curves and shapes. We leaned forward, studying every motion.

“Get on there, girl,” Sarah said. “Don’t you be lollygagging here front of my porch!” The girl said nothing and moved on. She looked back over her shoulder.

“What you two gawking at?” Red’s mother said. “I’m gone tan your hide, boy, you don’t act like you got some sense. Mister Charlie, that go for you, too. Don’t you reckon your momma be missing you? Best get on home. I make you some more hoecakes tomorrow.”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said.

The next week, after a thunderstorm, Red and I caught some fat night crawlers in the grass behind the shack. We put them with sand and grass in an old bucket and tucked them in the shade of the house pilings. The next afternoon, we carried the bucket to a little pool on Flag Run, near the school, with our cane poles and a burlap sack.

The bullheads were biting, and each of us was bringing one in with nearly every cast. We hoisted them up, gasping and sucking, their bellies yellow in the sunlight, onto the bank. We unhooked them as quickly as we could, put them in the sack in the stream, weighted the mouth of the sack with a big rock, and baited our hooks. When we ran out of night crawlers, we started to search the marsh grass along the stream for crickets.

“What you two doing?” the colored girl asked. Her hair was tied in braids. I recognized her. She was the girl we had studied from Red’s mother’s porch.

“Who spying?” Red asked.

“Alreda,” she said. “I ain’t spying. What you doing?”

She looked pretty in a flowered smock made from a flour sack.

“Fishing,” I said.

“We catching crickets,” Red said.

“You a cute white boy,” she said. “I seen you at Red’s. What your name?”

“Charlie,” I said.

“Charlie,” she said. She closed her eyes. “Mr. Charlie.”

“Don’t you be studying about no name,” Red said. “We trying to do us some fishing. Why don’t you get on?”

“Mr. Charlie, you want to see my titties?” she asked.

“I mean it, girl!” Red said. He picked up a clump of sod.

Alreda lowered the front of her smock. She let me look, then pulled it back over her shoulders.

“I show you my jellyroll for a penny, Mr. Charlie,” she said.

“He ain’t got no penny!” Red said. He threw the sod. It landed with a smack on her ankle.

“You little nigger!” she said.

Red picked up another clump. “You get on!” he said.

Alreda scurried up the bank and out of sight.

“Look here, Charlie,” he said. “Look the size of the damn cricket was under that sod.”

Red and I gathered a few more crickets in my handkerchief. We baited our hooks and caught more bullheads and slid them in the burlap sack. Then we gathered our poles and headed to Red’s house.

“Look here, Momma,” he said, hefting the sack.

Sarah smiled. “I got some corn meal. Clean them and I’ll cook them up for supper.”

Red found a bowl and a knife in the kitchen. We carried them and the sack to the marsh grass on the other side of the road. Red pulled a bullhead from the sack.

“Them spines, see, you don’t want one to poke your hand, Charlie. Sting like hell.” He cradled the bullhead between his fingers and cut the skin around its head. He cut the skin around the spikes and pulled it back, pinching with his thumb against the knife blade. He threw the skin in the grass. Then he ran the blade down the backbone to cut the fillets. He tossed the head and spine into the grass. He held the fillets up.

“See yonder?” he said. He put the fillets in the bowl. “Now you try one.”

I pulled a bullhead from the sack and rested its belly between my fingers.

Red nodded. “That’s fine,” he said. I began to cut the skin.

“Don’t you be giving Alreda no pennies,” Red said. “She show you that jellyroll for free.” I looked up. He was grinning.

“Well,” I said.

Red was right. Alreda would display her charms for nothing. But we also discovered the wonders a penny could buy. Alreda would sway and shimmy before us, bare as the day she was born. For another penny she allowed us to touch. With her eyes she guided us to touch in ways she liked. At these moments I could feel my heart beating to the tips of my fingers, and my hand trembled.

“Don’t you be skittish, Mr. Charlie, you doing good,” she crooned. Her voice washed over me like warm rain. I closed my eyes. I could hear her breathing. I felt I was floating, nudged by wind like a leaf on water.

That fall, I didn’t see Red at Miss Quesinberry’s one-room school. When I asked Miss Quesinberry about it, she told me he was attending a special school just for Negroes.

“Well, what’s wrong with this school? Why doesn’t Red come here, like before?”

“He’s colored, Charles. The district had overlooked it. But the new constitution strictly forbids the races going to school together. That’s all. There’s nothing wrong with anything.”

A tall boy on the bench behind me snickered. “Aw, he misses his little nigger friend,” he said. He tweaked at one of the temples of my wire rims.

“Mason Davis, you hush this instant!” Miss Quesinberry said. “You are never to utter that word inside these walls. Do you understand me?”

The boy slouched behind his desk.

“Well, do you?” Miss Quesinberry leaned over my desk. The wattles of her neck trembled. Her hand clenched the strop.

“Yes, ma’am,” the boy said.

“All right, then. Open your books. We’ll start our lesson,” Miss Quesinberry said. The books were brand new. The ink smelled like enamel paint when I turned a page. “Commonwealth of Virginia” was stamped on the fly leaf. When the school superintendent visited, he said we had new books so we wouldn’t have to use old ones that had been touched by colored children.

After school I walked to Red’s house. He was sitting on the porch, holding the Aesop’s Fables. He didn’t smile when he looked up.