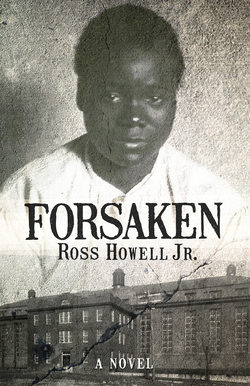

Читать книгу Forsaken - Ross Howell - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1.

My Testament

I was born Charles Gilbert Mears on August 21 in Southampton County, Virginia, during the financial panic of 1893. Mother told me the midwife moved her pallet onto the gallery to catch the breeze. She spread damp cloths over my mother and the two of them prayed for nightfall. The midwife sang, “Bend down, Jesus, bend down low!” I was born at twilight. Mother said from that evening on nothing was so restful to her as listening to the ratchet of katydids in the gloaming.

I never knew my father. In the tintypes he is a big man with a full beard. Mother looks slender as a lily next to him. The month before I was born, he traveled west to find work. The Southampton Bank & Trust failed and took his business with it. He never returned to my mother and me, but never did I hear her speak an ill word against him.

Before the panic my father had a thriving freight business with three heavy wagons, teamsters who were sober and reliable, and six pairs of mules. For a while he made ends meet by bartering to haul goods and equipment. Then even grain for the mules grew scarce. He sold the mules, but no one had money for the wagons. They were all that was left, abandoned in a field behind our house. I remember leaping from their sideboards to slay Yankee cavalrymen, the rusty wagon springs creaking. When the days grew hot, I rested in their shade, listening to cicadas in the trees. Beyond the wheel spokes the wide, barren fields shimmered in the sun.

The money from the mules my father gave to my mother. He kept enough to make passage to Provo, Utah. He was hired as a laborer to build a railroad spur from Salt Lake. My parents exchanged letters until after I was born. Then my mother’s envelopes were returned. Rumor had it Father was killed in a brawl with an Irishman. I didn’t know if that was true or if he simply abandoned us.

Mother insisted I should never take it as an omen, but on the night of August 21 in 1831, the slave Nat Turner led the Southampton insurrection. The old people where I grew up still remembered. Seventy Negroes marched from plantation to plantation, using knives, axes, and sickles to butcher white people. Under Turner’s order, no firearms were used, since the reports would have alerted neighboring plantations. Turner himself carried a broadsword. Fifty-eight whites—men, women, and children—were slaughtered. Militias quelled the rebellion and the reprisals were brutal. Turner confessed to his crimes and was hanged by the neck. His body was drawn and quartered. It was said a plantation owner had a slave fashion a satchel with Turner’s skin.

An old man lived alone in a shack near our land. He claimed when he was a boy my age he hid under the stone foundations of his house as the slaves of Turner’s rebellion set it alight. They had murdered his parents inside. He said the slaves spoke in tongues he had never heard and their eyes gleamed red in the firelight. I listened, slapping at mosquitoes, breathless.

People said the old man was daft. He seemed to pass his hours in a world of dreams and phantasms, muttering to himself like a mad actor on the stage. People living nearby sometimes heard blood-curdling shrieks at night, and claimed he was a drunk, addled by bad whiskey. But never once did I see him imbibe, or smell spirits on his breath, or discover tell-tale jugs hidden in his hovel. Though he scared me, I loved to hear his talk. My mother never discouraged my visits. She would wrap a meal of cornbread and bacon for him, usually with beans or chickpeas.

The walk home after one of my visits was a torture of shadows and crickets and rustling marsh grass. Sometimes the old man would show me an artifact he kept wrapped with canvas and twine in his wood box. He said it was a leg bone from Nat Turner’s skeleton, given him by a doctor said to have assembled it after the slave was mutilated. The old man let me touch it with my fingertips, gazing wide-eyed on it himself as if he held a relic from the holy land.

The bone might simply have been carried in by one of the old man’s hounds. The story of it could have been imagined from beginning to end. But as he spun his tale, sitting on his haunches like a wild creature, his eyes gleaming, his unkempt beard flecked with spit, terror sprang up in the Southampton fields beyond his cabin walls. Rainwater in puddles after a storm was thick with blood. Birdsong echoed with the screams of dying women and children. Scythes and axe blades glinted in moonlit pastures. Or so it seemed to me as a boy.

Nat Turner could recite whole books of scripture from memory. His intelligence was a wonder to local white clergy and a miracle to the Negroes who heard him preach in the open fields. When he was executed, he claimed an angel had visited him. The angel had told Turner he would see a sign when it was God’s will for him to massacre the people who enslaved him. The summer of the insurrection an eclipse blotted out the sun. After the rebellion colored people could not congregate to worship unless supervised by a white pastor. Laws prohibited teaching a slave to read or giving a slave a book, even the Bible, anywhere in Virginia.

Some evenings after supper Mother would sit with me in the parlor and read the scriptures.

“From the Gospel of Matthew, Charles,” she said, her glasses perched at the tip of her nose. “‘Lord, when saw we thee an hungred, and fed thee? or thirsty, and gave thee drink? When saw we thee a stranger, and took thee in? or naked, and clothed thee? Or when saw we thee sick, or in prison, and came unto thee? And the King shall answer and say unto them, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.’”

“Mother, what is ‘an hungred?’” I asked.

“A person who’s starving,” she said.

“And ‘the least of these’?”

“The helpless.”

“I want to help,” I said. I was six years old.

“You’re a good boy, Charles,” my mother said.

When I was ten she passed away. I was taken in by her maiden aunt. When I matriculated at the College of William & Mary, I was so pious the other boys called me “Preacher.” I led Bible classes at the college chapter of the YMCA and a Temperance prayer group for young men on Saturday nights. Not one Sunday did I miss service at the Methodist church by campus. But in our yearbook my classmates named me “most likely to bum tobacco.”

Often my friend Fitzhugh Scott and I would sit on the steps of our boarding house, gazing across the green to the old Colonial Governor’s mansion, where Thomas Jefferson sometimes dined as a student. We liked to talk poetry or religion. Fitz leaned against the steps, legs akimbo, while I smoked.

“Well, you have a point, Preacher,” he said, loosening his collar. His sunburned cowlick bristled through a coat of pomade. “Transcendentalism is not Christianity. But it’s hardly pagan. Wouldn’t you say Walt Whitman voiced Christian ideals? And lived them?”

“I suppose,” I said.

Soon after, my friend died. Studies and devotions seemed trivial then. I felt Death was stalking me, staring at me from the pages of books. I left college, taking a job at a newspaper in Hampton. In the daily tramp of events I believed I might rejoin the living.

That’s how I came to report on the trial and execution of Virginia Christian. What follows is my account of what happened, then and after. I like to believe I’m telling the truth. But I’ve learned the truth hides somewhere in the shadows of what happens.