Читать книгу The Irish Are Coming - Ryan Tubridy - Страница 10

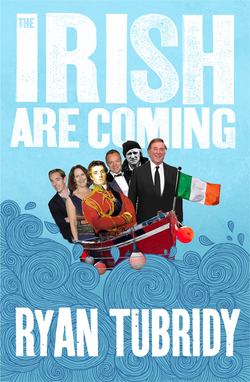

2 THE COMEDIANS

ОглавлениеIF YOU WANT TO SEE how much Anglo-Irish attitudes have changed over the last decades, just take a look at the humour. The Bernard Manning era when every paddy was an idiot and ‘How many Irishmen does it take to change a lightbulb?’ jokes were ten-a-penny have long gone. It would be like doing a joke about a Pakistani or a black woman or a gay man: it’s not only politically incorrect but can be illegal and every right-thinking person considers them bad taste. Of course, in Ireland we’re allowed our own self-deprecating humour but it’s got to be on our own terms. We’ll crack a joke about ourselves and call ourselves paddies – but the British are not allowed the paddywhackery now, and some Irish people even got a bit hot under the collar in the 1970s when Dave Allen dipped into it.

Perhaps it’s because it’s not too long ago that the Irish were seen as Punch magazine cartoon images: the potato-eating famine refugee, the drunk navvy or the balaclava-clad terrorist. As recently as the 1980s and maybe the early 90s these were the stereotypes propagated, particularly in right-wing elements of the media. Every Irish comedian who came over to Britain from 1967 to 1997 had to drop in a few gags about terrorism just to get it out of the way because otherwise it was the elephant in the room. But the peace process changed everything, virtually overnight. It changed the acceptability of being Irish in Britain, it changed the nature of comedy and it changed the portrayal of Ireland in the media. Neil Jordan’s 1992 (pre-peace-process) film The Crying Game was revolutionary enough for showing an IRA man falling in love with what he thought was the girlfriend of a British soldier. But now in 2013 we see Gillian Anderson in The Fall, which is about a psychopath running around Belfast killing women and there’s not an ArmaLite or a terrorist cell in sight. It’s a huge cultural, political, historical shift in the right direction.

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, comedians had torn up their jokes about terrorists, drunken builders and women with twenty-five children. All that is a clichéd bore. We don’t laugh at Irishness any more; we laugh at what’s genuinely funny – and that’s what’s made it possible for us to enjoy the ironic post-peace-process sitcom Father Ted. Maybe in the past we would have been a bit more sensitive about the three priests banished to Craggy Island for their misdemeanours but now it’s just pure comedy and we’re all laughing together.

It’s not that the Irish are po-faced when it comes to humour. On the contrary, we use it to end an argument, to alleviate sadness or to poke fun at ourselves, but all self-references must be on our terms. And if there’s one thing that’s always been fertile territory for Irish humour, it’s having a dig at authority. As a people we’re instinctively, unfailingly anti-authoritarian, probably because of all those centuries of resisting British authority. It’s bred into us from an early age; it’s in the water. The first comedian I’m going to talk about in this chapter is the one who first made his name for attacking the biggest authority of the twentieth century: our very own Catholic Church (those of a sensitive disposition may want to make the sign of the cross before reading on).