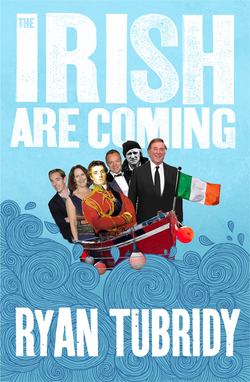

Читать книгу The Irish Are Coming - Ryan Tubridy - Страница 11

DAVE ALLEN: the funniest man in the pub

Оглавление6 July 1936–10 March 2005

I’m bothered by power. People, whoever they might be, whether it’s the government, or the policeman in the uniform, or the man on the door – they still irk me a bit. From school, from the first nun that belted me …

I remember as a young boy, pyjamas on, sitting on the couch beside my dad and watching him as he chuckled while watching a man on the television. The man was roughly my dad’s age (ancient) and appeared to be drinking a whiskey with one hand, occasionally smoking and repeatedly removing non-existent lint from his trousers. It was Catholic Ireland so when this mild-mannered man dressed up as a bishop and started doing fart jokes, I realized we were witnessing a bold man – a very funny, bold man.

The comedy that struck a chord in our house when I was growing up ranged from The Muppet Show through to Tommy Cooper via Dermot Morgan and Basil Fawlty and on to Dave Allen. As a family, we appeared to enjoy anarchic yet droll humour that was rarely vulgar but always clever with a twist of mischief. Dave Allen embodied all of these traits. It was dad humour. Everyone’s dad loved him. He was that intriguing paradox of being gentle but cutting, intelligent but accessible. You didn’t need a degree to get his jokes – just an ability to share his observations.

Allen was born in Dublin and his dad, Cullen, was a journalist and celebrated raconteur who often shared a bar counter with Irish novelist and wit Brian O’Nolan (aka Flann O’Brien aka Myles na gCopaleen). His mum, Jean, was a nurse who happened to be born in England. With a story-telling father and an English mother, it’s perhaps no wonder Dave Allen ended up sitting on a stool on British TV telling funny stories for a living.

His Irish background would very much inform his future career and the substance of his routines, so many of which revolved around the Catholic Church and a questioning irreverence towards that institution and all who sailed in her. He was a pupil at Beaumont convent school, which was run by nuns whom he described as ‘the Gestapo in drag’. Unhappy as he might have been at the time, these nuns would go on to inform much of Allen’s later comedy: ‘I arrived at this convent, with these Loreto nuns, and the first thing that was said to me was: “You’ll be a good boy, won’t you?” And I went: “What?” So they said: “When you come in here, you’ll be a good boy, because bold and bad and naughty boys are punished!” And I’d never seen a crucifix before. All I could see was this fella nailed to a cross! I thought: “Shit! I will be good!”’

He went on to Terenure College in Dublin, another Catholic school which, he recalled, combined cruel corporate punishment with ominous talk of sex and its association with the Devil himself. Somewhat unsurprisingly, Allen was expelled and left school altogether at the age of sixteen. A few journalistic jobs followed (clerk at the Irish Independent, writer with the Drogheda Argus) before he decided to try his luck in London, having run out of options at home. His attempts to get a job on Fleet Street came to nothing but he was more successful at Butlin’s, where he got his first taste of audience approval as a Redcoat. Sitting telling jokes and stories between the evening’s acts suited him right down to the ground and he decided to focus on comedy full-time. First he changed his name from the alien linguistic mouthful David Edward Tynan O’Mahony to the less complicated Dave Allen (a stage name that cannily secured alphabetical top-billing). He was still Irish – just not quite so much.

It was the early days of television and Allen seized the opportunity when he appeared on the BBC talent show New Faces. He toured with the singer Helen Shapiro and by 1963, he was joined in the support-act dressing room by up an unstoppable force of nature called The Beatles. It was in Australia where he got his biggest break when he hosted Tonight with Dave Allen – a show that ran for eighty-four episodes. (In an odd romantic twist I can’t resist mentioning, Allen was linked to the feline singer Eartha Kitt who appeared on the weekly show twice. The pair were seen holding hands in public but nothing was to come of it and the story died. Shame, really.)

Back in the UK in 1964, with an Australian wife in tow instead of an American sex kitten, Allen built up a reputation as host of Sunday Night at the Palladium and as resident comedian on a show hosted by another Irishman abroad, Val Doonican (see Chapter 8). By 1967, he was established enough to go it alone when he started hosting Tonight with Dave Allen on ITV and it was here that the character we all came to know and admire emerged with barstool, half-smoked cigarette and a glass of what we all presumed was whiskey. The drinking and smoking put you at your ease. You felt you could sit there and have a dialogue with him. He’s like the funniest man in the pub. Now, of course, the funniest man in the pub can sometimes be the funniest man in the pub and he can sometimes be the pub bore, but Allen really was the funniest man in the pub and you wanted to sit there and listen to his stories all night, perhaps with a glass of your own in hand.

A mixture of monologues and sketches made the BBC take notice and it was on this channel that The Dave Allen Show and Dave Allen at Large dominated the comic airwaves between 1968 and 1979. Allen’s experience of a Catholic education and life in a near-theocratic society informed his material, and sex and the demonization of it by the Church loomed large too. The confession box was a regular target. Allen described it as akin to ‘talking to God’s middle-man, a ninety-five-year-old bigot’. Back home in Ireland, though, few in authority saw the funny side of Dave Allen’s jokes and in 1977 his shows were banned on RTÉ. The Church was still a very big noise at the time, and perhaps viewers were writing in saying ‘Get this filth off the air!’ But it did him no harm to be banned in his home country; it all helped to build the anti-authoritarian image we know and love.

As Allen’s star ascended in London and beyond, there were typically Irish rumblings emerging from the auld sod where he was being chastised for mocking Irish people in his routine. Reporting on an awkward-sounding encounter with the comedian, writer (then Irish Times journalist) Maeve Binchy wrote:

Yes, of course he gets attacked by people for sending up the Irish, oh certainly people have said that there’s something Uncle Tom-like about his sense of humour, an Irishman in Britain making money by laughing at Irishmen, but he gets roughly the same amount of abuse for laughing at black people, at Jews, at the Tory Party, at the Labour Party, at the Pope, at vicars. People become much more incensed if he makes fun of someone else’s minority group than their own, he thinks.

The point was that the Irish didn’t want to feel the British were being given ammunition with which to mock them; the patronizing attitudes during those centuries of hurt were still too keenly felt.

It was in the mid-70s that Allen’s irreverence became a national talking point. Dressed as the Pope, the comedian pretended to do a striptease on the steps of the Vatican to the tune of ‘The Stripper’. Protests followed, with letters and calls to the BBC complaining about the disrespectful scene. And the complaints, as so often can be the way, were the making of him. Allen returned to Australia to film four shows for which he was paid AUS$100,000 and when he got back to England, he sold out in theatres across the land. It wasn’t just the Church that bore the brunt of his humour: he took a dim view of politicians, and Protestant Northern Irishman Ian Paisley was a frequent target. Anyone in any kind of authority was fair game.

By the 1980s, Dave Allen’s casual story-telling technique and some of his reference points were seen as out-dated by a new set of brash, fast-talking, so-called alternative comedians whose style pretty much reflected the era. It was the shouty political comedy of Ben Elton, Alexei Sayle and Ade Edmondson audiences wanted to watch – for a while at least. Allen announced his official retirement but staged a brief comeback on the BBC in 1990 and on ITV in 1993 that led him to explain: ‘I’m still retired, but in order to keep myself in retirement in the manner in which I’m accustomed, I have to work. It’s a kind of Irish retirement.’

The comeback was restricted due to poor health but there was time for Allen to lob one more grenade at the establishment when he told his now infamous ‘clock’ joke: ‘We spend our lives on the run. You get up by the clock, you go to work by the clock, you clock in, you clock out, you eat and sleep by the clock, you get up again, you go to work – you do that for forty years of your life and then you retire – what do they f***ing give you? A clock!’

Unbelievably, some ‘high-minded’ members of the British parliament took the BBC to task for lack of taste because of the use of the F word in the punchline. The Beeb kowtowed but Allen was unapologetic: ‘I’m Irish and we use swearing as stress marks.’

Slowly, his career was coming to an end but not before he received belated recognition by the bright young things of British comedy, who wisely awarded Allen the lifetime achievement award at the British Comedy Awards in 1996. Looking back on his career, Allen wondered aloud where his comedy came from and ended up thanking a comic deity for the nuggets that fuelled his career: ‘I don’t know if there’s somebody out there, some god of comedy, dropping out little bits saying, “Here, use that, that’s for you, that’s to keep you going.”’ Personally, I think his Irishness was the root of his material; it gave him the anger and anarchy.

The British public heard Dave Allen’s last performance on BBC Radio 4 in 1999 before he retired fully and indulged in his favourite hobby, painting. He had already given up the sixty-a-day smoking habit, telling friends: ‘I was fed up with paying people to kill me; it would have been cheaper to hire the Jackal to do the job.’ But it still caught up with him and he died of emphysema in 2005 while his second wife was pregnant with a son he would never meet (he had two children from a previous marriage).

Towards the end of his life, there was a renewed respect for Dave Allen with comedians like Jack Dee, Pauline McLynn, Ed Byrne and Dylan Moran citing him as a significant influence. On hearing of Allen’s death, Eddie Izzard described him as ‘a torchbearer for all the excellent Irish comics who have followed in recent years’.

There have been Dave Allen revivals on the telly recently and when I watch them I can see exactly what my dad saw in him in the 1970s. It’s observational comedy that hits a nerve, that makes you go ‘Yeah, I agree, I’m right with you there.’ It’s surprising how little has dated, even in these days when the Church doesn’t have such a fierce hold on our souls. I’d like to take this opportunity to say to Dave Allen what he always said to us at the end of his shows: ‘Goodnight, thank you, and may your god go with you.’