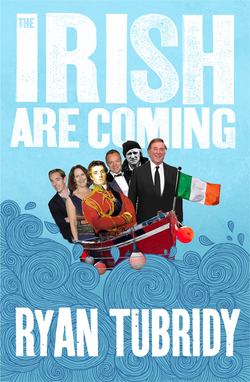

Читать книгу The Irish Are Coming - Ryan Tubridy - Страница 15

Оглавление3

THE CHAT SHOW HOSTS

THE MINUTE MICHAEL PARKINSON comes on television you can tell he is a Yorkshireman, while the Davids – Dimbleby and the late Frost – sound a bit posher and more southern, and Jonathan Ross has a working-class geezer accent. The point is that, rightly or wrongly, you think you know straight away whether they are descended from aristocrats or brickies, went to private school or the local comprehensive, and say ‘toilet’ rather than ‘loo’. Conversely, when someone from Ireland comes on television in the UK, the accent is classless. You can’t tell how many bedrooms there were in their childhood home or whether their family employed servants or worked below stairs themselves. The fact that we don’t fall neatly into the British class system helps the Irish when trying to make it in the UK. It makes us neutral – which is a good thing when our job is to draw other people out. We don’t have any chips on the shoulder; we just want to ask questions because we’re curious.

The British perceive the chatty Irish chat show host as genial and unthreatening. Guests know they’re not going to be Paxmanned over the head or joked into a corner by one too many one-liners. A lot of modern chat shows have the host rat-a-tatting at guests, both here and in the United States (think Leno and Letterman) and the substance of the interview can get lost along the way.

Now, chat shows are a subject I know a bit about. The Late Late Show has been on RTÉ in Ireland for fifty-one years, making it the world’s longest-running chat show apparently. Gay Byrne presented it for thirty-seven years, Pat Kenny had it for ten, and I took over five years ago. I always say it’s not my show – the show is like the Tardis and I’m just the latest Doctor – but I was enormously honoured to be asked. It’s a big challenge because it is 100 per cent live every Friday night from half nine through to midnight, and it runs for thirty-eight weeks a year. We have everyone on, from politicians to pop stars, Hollywood royalty to the individuals making headlines in any given week. I always make it my business to go to the dressing room beforehand and look guests in the whites of the eyes so they can see I’m not too scary. Lots of celebrities are nervous because we’re live – and I know how they feel because I’m often nervous as well – but you just go out the other side of the curtain and have some fun.

With a show like that back home, why have so many of our chat show hosts crossed the water to grace UK TV screens? Well, the bigger audiences must have been a draw. It must be nice to get 8 million viewers rather than seven hundred thousand. Gay Byrne flirted with it for a while before deciding against a move, but many others have filled prime-time spots on British screens over the last fifty years. Most of them are seen as ‘charming’, ‘non-threatening’ and ‘affable’, words that are quite often associated with the Irish. But the influence of these charming men has gone far beyond a bit of superficial television, as I’ll explain with reference to some of our greatest TV exports.

EAMONN ANDREWS: Mr Congeniality

19 December 1922–5 November 1987

He let people be the stars.

– Val Doonican

Any broadcaster worth his salt knows that to understand the history of Irish broadcasting you need to acquaint yourself with the granddaddy of them all. Eamonn Andrews is probably the patron saint of Irish television, having been there from the beginning, and then for decades he spun the two plates of Irish and British presenting jobs. He was a monolithic figure who casts a long shadow in this field.

My first memory of him is as a big, good-natured man who clasped a large red book while proclaiming to an unsuspecting victim ‘This is your life!’ – at which point some dramatic music swirled out of the ether and the credits rolled on a show that was effectively a funeral for someone still alive. I was too young to notice or care that the man had a distinctly Irish accent but he was always considered ‘one of ours’ and the fact that his surname was the same as my mother’s maiden name (although there’s no relation) made me pay a bit more notice.

In the modern reception area of Ireland’s national broadcaster, RTÉ, there’s an impressive bronze statue of the broad-shouldered Andrews, arms folded. He looks authoritative and important and could be fierce if it wasn’t for a genial smile on his sculpted face. People pass him by on their way into television studios, mostly ignoring the presence of this broadcasting giant. But his story, that of a working-class boy from Dublin who conquered the British airwaves, is irresistible and too interesting simply to skip by in a hurry.

Andrews’s dad was a carpenter with the Electricity Supply Board but also a drama enthusiast, an interest that proved hereditary. A fan of Gary Cooper and Spencer Tracy, young Eamonn Andrews was drawn to the gentle-giant characters of American cinema despite the fact that he was painfully shy as a child; according to his biographer Tom Brennand, ‘He was born to blush, to be embarrassed, to be pathologically shy, and he grew up almost too timid to speak to anyone.’ In fact, bullying became such a problem for the tall, slightly odd-looking boy at Dublin’s Synge Street School that he took up boxing. This was a clever move for two reasons. For starters, he was never bullied again, and secondly, although he didn’t realize it at the time, it would help to launch his media career.

A working-class lad, Eamonn attended elocution classes to make him sound less rough around the edges and started to get occasional work as a boxing commentator on Irish radio. His love of boxing and an interest in journalism dovetailed neatly in 1944 when he began commentating on and competing in the amateur boxing championships. The ambitious sportsman jumped straight from the commentator’s box into the ring before going on to win his final fight, becoming junior Irish middleweight champion in 1944.

By this time, Andrews was hungry for the limelight and wanted to broaden his horizons. To this end, he started to bombard the BBC. ‘A constant stream of letters poured across the Irish Sea from the Andrews household to Broadcasting House,’ he recalled. ‘Nearly all were answered politely, but all said the same thing – “Sorry, but … ”’ Attempts to catch the attention of BBC bosses proved fruitless until 1950 when he was asked to host Ignorance is Bliss, a comedy quiz on BBC radio. Five years after the end of the Second World War, the Beeb were looking for accents that weren’t as plummy as those that had previously characterized the station. Eamonn Andrews epitomized this new ‘sound’. They also liked the way he was perceived by listeners (and later viewers): ‘He sells an ordinariness. The British public quite like that, they like to think they could do what you can do if they like you.’ He was Everyman: a genial Irish Everyman with a broad grin.