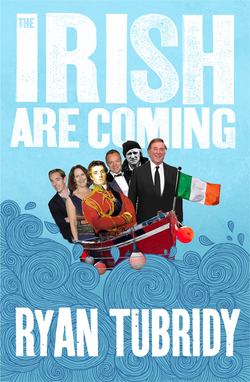

Читать книгу The Irish Are Coming - Ryan Tubridy - Страница 8

PETER O’TOOLE: the Celtic dynamo

ОглавлениеBorn 2 August 1932

God, you can love it! But you can’t live in it. Oh, the Irish know despair, by God they do. They are Dostoyevskian about it. ‘Forgive me Father, I have f**ked Mrs Rafferty.’ ‘Ten Hail Marys, son.’ ‘But Father, I didn’t enjoy f**king Mrs Rafferty.’ ‘Good son, good.’

Peter O’Toole is less Irish than Richard Harris in many respects because Harris lived in Ireland till adulthood whereas O’Toole was only a boy when the family emigrated to the UK. But although he had an English accent and took British roles, he always played the Irish card – and when it came to hellraising he was destined to be the last man standing.

O’Toole’s father moved the family from a ruggedly desolate part of Connemara to a Leeds working-class housing estate – what O’Toole later called ‘a Mick community’ – in search of a better and brighter future. Full of Irish ex-pats and hard-nosed working men, as streets go these were meaner than average. Three of his childhood friends would later be hanged for murder. This was no gilded cage and yet a cursory look at the O’Toole parents gives us some insight into what was to come. Dad, Patrick Joseph O’Toole, was an illegal gambler with a fondness for alcohol and Mum, Connie, loved literature and read stories to young Peter when he was a boy. And so, hailing from Ireland’s wild west, reared in a tough part of town in a home that mixed literature and booze with a whiff of rebellion, the foundation stone of the house that Peter would build was laid very early on.

Not unlike Richard Harris, the man who would ride shotgun with him later in life, O’Toole was a poorly child, afflicted as he was with TB, a stammer and poor eyesight. And during his school days he felt the wrath of religious rigour, with nuns who tried to beat him out of left-handedness. O’Toole dedicated a corner of his autobiography to the women in black who tormented him as a youngster, describing the day they went for him after he drew a picture of a horse urinating: ‘Flapping, frantic as startled crows, rattling beads and crucifixes, black hooded heads, black winged sleeves, white celluloid breasts, hard, white bony hands banging, the brides of Christ got very cross indeed.’ Sounding more and more like Alex or one of his droogs in A Clockwork Orange, he continues: ‘They tore up my drawing and began to hit me. This made me more cross than those sexless bits of umbrella could ever be so I joined the dance and hit and tore. ’Tis only a gee-gee having a wee-wee you cruel, mad old ruins.’

Later in life, when he criticized the Catholic Church in general and his Catholic upbringing in particular in an interview in Playboy magazine, O’Toole was surprised to receive a sackful of post from angry priests and nuns: ‘They were shocked. I wrote back saying I was shocked – what were they doing reading Playboy?’

But back to his younger, less sinful days: O’Toole left school early and earned a crust by packing cartons at a local warehouse before landing a job at the Yorkshire Evening News, his local paper, where he went from tea-boy to journalist to bored wannabe: ‘I soon found out that, rather than chronicling an event, I wanted to be the event.’

Abandoning journalism, he looked to drama as a potential path before being grabbed from his nascent career by a stint of National Service that saw him joining the Royal Navy as a signals operator. This unlikely nautical adventure was followed by a further bid for theatrical glory. Aiming for the top, O’Toole tried his hand at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) but was refused entry on the basis of his academic shortcomings. The flighty would-be actor blew his top and the tirade was fortuitously overheard by RADA principal Sir Kenneth Barnes, who set up an audition that O’Toole passed, resulting in a place at one of the world’s foremost theatre schools. It wasn’t long before the lithe Irishman was treading the boards and propping up bar counters around London.

O’Toole’s acting career was firmly launched in 1959 when he starred in the play The Long and the Short and the Tall by Willis Hall, directed by Lindsay Anderson (the same director who had launched Harris, soon to be O’Toole’s drinking buddy). His understudy was one Michael Caine, who quickly came to realize that the worst part of being Peter O’Toole’s understudy was wondering whether the star would return from the pub before the curtain rose. Night after night, O’Toole kept Caine waiting until the last minute before cantering past and straight on to the stage. Young Caine was charged with sourcing parties, alcohol and women, tasks that drove the beleaguered understudy to comment: ‘I’d have made a wonderful pimp.’

There’s always a delicious irony to the idea of an Irishman taking on the role of a British national treasure and so it is entirely appropriate for me to dwell on one of British cinema’s twentieth-century masterpieces, Lawrence of Arabia. The lead role in this gargantuan 1962 production was originally to be played by Marlon Brando, then Albert Finney, but ultimately it came to Peter O’Toole. And by the end of filming, O’Toole was giving Lawrence a run for his money when it came to exploits in the Middle East.

Egyptian film star Omar Sharif became a close friend, a man with whom he had way too much fun in Beirut’s hot spots. Asked by a journalist if that entailed getting up to no good, O’Toole replied with a grin: ‘Oh darling, do you consider it to be no good? We considered it to be very good indeed.’ Among the less salubrious exploits was the night he threw a glass of champagne in a local official’s face, leading co-star Alec Guinness to comment ‘O’Toole could have been killed, shot or strangled and I’m beginning to think it’s a pity he wasn’t.’

The film involved a gruelling and physically brutal schedule but the results were worth it. Seriously. I watched it recently and thought it was pretty trippy. Back in 1962, they knew a star was born and O’Toole lapped it up. ‘I woke up one morning to find I was famous,’ he remarked. ‘I bought a Rolls-Royce and drove down Sunset Boulevard, wearing dark specs and a white suit, waving like the queen mum. Nobody took any f**king notice, but I thoroughly enjoyed it.’

And yet, the world did notice Peter O’Toole. It was hard not to. Always wearing his trademark green socks, O’Toole played up his Irishness and floated around town, drinking lavishly and followed by wisps of Gauloise cigarettes that he smoked in an ostentatious cigarette holder. Described by a friend as smelling ‘like a French train’, Peter was a committed smoker. When John Goodman, his co-star on King Ralph (1991), offered to get him an ashtray after he flicked his ash on the ground, he cried, ‘Make the world your ashtray, my boy.’

This was the stuff of O’Toole legend: a half-sozzled, licentious thespian with swagger and a talent to back up all the talk. As part of a set of working-class boys who made good, O’Toole, Harris and Richard Burton became their own West End rat pack, lascivious lounge lizards who took the art of candle burning to new levels. Looking back on those days, O’Toole is unapologetic: ‘I do not regret one drop. We weren’t solitary, boring drinkers, sipping vodka alone in a room. No, no, no: we went out on the town, baby, and we did our drinking in public! … It was a fuel for various adventures.’ Such fuel allegedly saw him go for a drink in Paris one evening only to wake up in Corsica.

The fuel would come in handy on one of his visits home to Ireland. There was the time O’Toole stayed with his old friend, the movie director John Huston, at his estate in the Wicklow Mountains. The two boys had had a long night of it when we join the story as recounted by O’Toole:

Came the morning, there was John in a green kimono with a bottle of tequila and two shot glasses. He said: ‘Pete, this is a day for gettin’ drunk!’ We finished up on horses, he in his green kimono, me in my nightie in the pissing rain, carrying rifles, rough-shooting it – but with a shih-tzu dog and an Irish wolfhound, who are of course incapable of doing anything. And John eventually came off the horse and broke his leg! And I was accused by his wife of corrupting him!

As with Harris, the booze was blamed for damaging his health. There was a serious illness in 1976, when he required major surgery to remove his pancreas and part of his stomach; then he nearly died in 1978 after succumbing to a severe blood disorder. The booze certainly helped to destroy his marriage to Welsh actress Siân Phillips, from whom he was divorced in 1979. He later said he had studied women for a very long time, had given it his best try, but still he knew ‘nothing’.

O’Toole returned to work after his brushes with death but his 1980 Macbeth at the Old Vic made headlines for all the wrong reasons: ‘He delivers every line with a monotonous tenor bark as if addressing an audience of deaf Eskimos,’ wrote Michael Billington in the Guardian. The morning after the disastrous premiere O’Toole opened the door to journalists seeking his reaction and gamely laughed it off – ‘It’s just a bloody play, darlings!’ – but it must have rankled. Later he won his fair share of theatre awards, including a lifetime achievement Olivier Award, but dismissed them as ‘trinkets’.

By his seventy-first year, his film work had earned him seven Oscar nominations – two of them for the same character (he played Henry II in both Becket (1964) and The Lion in Winter (1968)) but none of those shiny statuettes. The Academy attempted to bestow an honorary award but O’Toole initially turned it down, telling the bewildered committee that he was ‘still in the game and might win the lovely bugger outright’ before urging them to ‘please defer the honour until I am eighty’. The Academy (and his daughters) convinced the contrary actor to change his mind and, despite his upset at the lack of booze at the event (apart from the vodka he managed to have smuggled in), Peter O’Toole took to the stage to accept the ‘lovely bugger’ in 2003.

As if to prove a point, he powered his way to the acting frontline once more when he was nominated for yet another Oscar following a classy performance as an ageing Casanova in the 2006 film Venus. It was as if he wanted to score a goal in extra time and, despite not winning the award, O’Toole proved he was still very much in the running. When he retired in 2012, saying, ‘The heart of it has gone out of me’, he was bowing out more or less at the top of his game.

Despite playing all those English establishment figures, he always remained an Irishman to the core, with a house in Galway as well as one in London. He played cricket for County Galway and often went to Five Nations rugby matches with the two Richards, Harris and Burton. There is a special place in any Irishman’s heart for watching England being defeated at rugby. We’re at one with the Scots and the Welsh on this. There’s a Celtic brotherhood of freedom-fighting, feisty people who have been oppressed by the English. So for the Irish, it’s sweet to win at Murrayfield and the Millennium Stadium but the sweetest victory of all is to decapitate the English rose at Twickenham – as I’m sure Harris and O’Toole would have agreed.

Harris has gone now, Burton went long ago, and O’Toole is the last man standing, bemoaning the fact that his drinking partners have left him alone at the bar, an act he considers ‘wretchedly inconsiderate’. But behind the beer goggles, who is the man that theatre critic Kenneth Tynan described as an ‘insomniac Celtic dynamo’? We’ll probably never know; even his own sister, Patricia, can’t figure him out. When she met an actress who was about to star with him, she asked, ‘At the end of the picture, will you tell me who my brother is? What goes on in there, in the f**king thing he calls a mind?’

It’s a question that may never be adequately answered but whatever it is that goes on in there, it helped produce a flamboyant bon viveur who became a legend in his own lifetime – both for his acting and for his hellraising. They simply don’t make ’em like that any more.