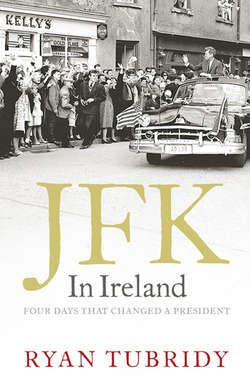

Читать книгу JFK in Ireland: Four Days that Changed a President - Ryan Tubridy - Страница 12

The Congressman in Dunganstown, 1947

ОглавлениеBack in the US once more, it was time to start fulfilling the family’s political ambitions with a precocious run for Congress in 1946. When John F. Kennedy announced his intention to run for office in a working–class, Irish–Italian district of Boston, the reaction was rather sniffy. One newspaper described the candidate as “ever so British”, a jibe that would be levelled at him throughout his life, in an ironic turn of events after the childhood taunts that he was “too Irish”.

Kennedy was at an ethnic crossroads of sorts. Irish–Americans felt he wasn’t quite one of them, complaining that “He never even went to a wake unless he knew the deceased personally.”22 Most candidates with Irish roots attended wakes whenever there was one to attend because it was a good way to canvas for votes while showing yourself as a caring member of the community, but Kennedy was cut from a different cloth and would have felt it inappropriate to attend a stranger’s wake. His East Coast American sensitivity was more dominant than his Irish showmanship.

Equally, Kennedy wasn’t as inclined to glad–hand as his grandfather, the über–Irish American politico Honey Fitz, had been. An early biographer noted that Kennedy “disliked the blarney, the exuberant backslapping and handshaking”.23 He came from a new breed of Irish–Americans, an emerging middle class who didn’t see the need to get drunk every night and moan about the Brits, but who also had no problem embracing their ethnicity. JFK wasn’t scared of his roots, they didn’t embarrass him and he certainly wasn’t going to let them get in his way as he stood on the first rung of the political ladder.

Despite the negative reactions, Kennedy’s eloquence and charm were such that he won easily, getting nearly double the votes of his Republican opponent, and this victory put him on the road to political greatness, although you wouldn’t have known it to look at him. Nearly every commentator at the time passed some class of remark on his boyish demeanour, his slight appearance and gaunt features. He was taking steroids for his spastic colon at a dose that caused osteoporosis in his lower back, and a back injury sustained during the war meant he was in constant pain. The steroids also triggered Addison’s disease, a disorder of the adrenal gland, which had caused him to lose weight. The extent of his health problems was kept hidden from the public, on his father’s advice, because it was felt that they might have hesitated to vote for an invalid.24

During JFK’s successful race for Congress in 1946 there had been several campaign parties at which Kennedy’s favourite Irish songs were sung: songs such as “Macushla”, “Danny Boy” and “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling”.25 His sense of Irishness was emerging strongly at this point, as evidenced by a holiday he took in the old country in September 1947 with the purpose of exploring his roots.

Before leaving America, the young Congressman made calls to track down some of his family connections in Ireland. One of these was to his aunt Loretta Kennedy Connelly, who happily obliged with directions for New Ross in County Wexford, a short trip away from where Kennedy would be staying. He went on to get a guidebook which came with a map, and that map is peppered with the letter ‘X’ beside places that interested him.26 He was eager to get to know the old country and investigate his family’s history there.

On 1 September 1947, thirty–year–old Congressman Kennedy arrived at Shannon airport for a three–week stay with his sister Kathleen. She had married the eldest son of the Duke of Devonshire and, despite being widowed after only four months, was still given the use of Lismore Castle in County Waterford, an extravagant holiday home owned by her late husband’s parents.

The guest list was like something out of an Agatha Christie novel, including Pamela Churchill and Anthony Eden (former British foreign secretary and future prime minister), Sir Shane Leslie (a writer and first cousin of Winston Churchill) and William Douglas–Home (a playwright). Kennedy stayed in the Queen’s Room, which afforded him river views; he would have been accustomed to such luxury, with the splendid homes his family occupied back in the USA.

One morning the future president went searching for his roots, taking Pamela Churchill with him. She must have been bemused. Until 1945, Ms Churchill had been married to Randolph Churchill, son of Winston, and had been linked with some of the more exotic men of the time, including the American broadcaster Edward R. Murrow and the Italian car magnate Gianni Agnelli. But on this particular morning, she was accompanying a skinny Congressman down the narrow, winding roads of New Ross. It didn’t take Kennedy long to find Dunganstown and, once there, he was directed along a rough track to a thatched–roof cottage, the home of Mary Ryan, a third cousin on his father’s side.

Their house was a far cry from the luxury of Lismore Castle, with sparse comforts, an outdoor toilet and chickens and pigs wandering in the yard, but John F. Kennedy was delighted to sit down and listen to Mary Ryan’s stories of his grandfather, Patrick, who had visited there thirty years previously, and other family members who had stayed behind in County Wexford during the Famine. Kennedy produced a camera and took some photographs, which continue to grace photo albums in the Dunganstown homestead.

Alas, in the time he spent there, Kennedy failed to make a significant impression as years later, the only recollections Mary Ryan and James Kennedy, another third cousin, had were physical. Respectively, they commented “He didn’t look well at all” and “Begod, and he was shook looking!” However, hospitality was forthcoming and tea was duly served to the young American and his aristocratic companion. Sixteen years later, the eyes of the world would focus on Mrs Ryan when she once more served her distant relative tea and cake but by then the circumstances would be utterly changed.

Lismore Castle, Co. Waterford, as it was in the early 20th century. It was here in 1947 that Congressman Kennedy came to stay.

Though Kennedy may not have made much impact, the time he spent with Mrs Ryan had profound resonance for him. As they drove away down the dirt track that afternoon, a wistful Kennedy claimed later that he “left in a flow of nostalgia and sentiment”. He turned to Lady Churchill for her thoughts on the visit and she offered pithily “That was just like Tobacco Road!” (a novel set amongst farmers struggling in the Great Depression of the 1930s). Flying towards Ireland on Air Force One sixteen years later, Kennedy would remember this moment: “I felt like kicking her out of the car. For me, the visit to that cottage was filled with magic sentiment. That night at the castle … I looked around the table and thought about the cottage where my cousins lived, and I said to myself, ‘What a contrast!’”27

One of the photographs taken by JFK when he visited the ancestral homestead in Dunganstown, Co. Wexford, in 1947.

Further evidence that he was beginning to feel his own Irishness more strongly comes from his support for a 1947 bill in Congress, proposing that post–war aid for the British should be contingent on their government ending Partition in Ireland. Rhode Island Congressman John Fogarty had introduced this resolution on a number of previous occasions, and would do so again later. The bill was never going to become law but it was an easy way for Kennedy to underline his Irishness with his Irish–American base and may well have reflected his own views on Partition at the time. It was defeated in Congress by 206 votes to 139, with 83 abstaining but JFK had laid his cards on the table. As far as the Irish nationalists were concerned, he was on their side.