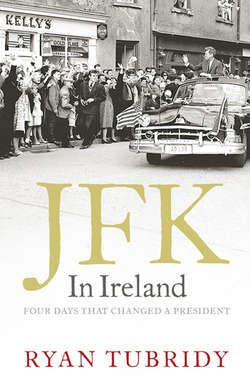

Читать книгу JFK in Ireland: Four Days that Changed a President - Ryan Tubridy - Страница 9

The Fitzgerald connection

ОглавлениеJust two years out of Harvard, Joe repeated family history by setting his sights above his social station and falling in love with Rose Fitzgerald, a member of one of the Boston Irish community’s first families. Descended from Thomas Fitzgerald, who had left Ireland in 1854, the Fitzgerald family had fared better than the Kennedys.

Rose’s father, John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, was one of Boston’s most colourful and mercurial characters. Though he studied at Harvard medical school, he only lasted two years there because he had one real passion, and that was politics. He knew that money couldn’t buy you social acceptability in the snobbish world of Boston high society, but political office was bound to help. Honey Fitz was the consummate Irish–American politican; a back–slapping wheeler–dealer with the gift of the gab. He became a Congressman in 1895 and then, most famously, Mayor of Boston from 1905–07 and 1910–12, the first Irish–American to be voted into that post.

As a teenager Rose Fitzgerald acted as hostess at many of her father’s political functions. In 1906, Joe Kennedy began to pursue her, although Honey Fitz didn’t warm to the young Kennedy. He was determined to protect his first–born daughter from this brash young man and did his utmost to keep the couple apart. In fact, he managed it for eight years, but Honey Fitz didn’t count on Joe’s sheer determination and while he was preoccupied by a low point in his political career in 1914, Kennedy struck and the two were married.

The modern epic that constitutes the Kennedy story begins here. In 1915 Joseph Jr was born, and Honey Fitz told anyone who would listen that his grandson would be president in the White House one day. In 1917 John Fitzgerald Kennedy came into the world, and in the ensuing years Rose would give birth another seven times.

Displaying a competitiveness that would prove somewhat genetic, Joseph Kennedy excelled in anything he applied himself to and found his niche talent was in the world of business. By the 1920s, Kennedy had made a fortune speculating on the stock market. His money was useful in a modern sense but his success wasn’t enough to impress the Boston Brahmins, whose only currency was class. Attempts to join country clubs in Boston were rebuffed. His father was still referred to by the Brahmins as “Pat the tavern keeper”7. Almost eighty years after his grandfather set foot on Boston harbour, the Irish were still being treated as second–class citizens and Joe Kennedy was fed up with it. He decided to start afresh in New York, where he moved his burgeoning family in 1927, claiming that Boston “was no place to bring up Catholic children”. Joe and Rose now divided their time between New York, Hyannis Port on Cape Cod, Palm Beach, Florida, and Boston. Joe became wealthier with every decade, bringing his ruthless and relentless energy to the stock exchange, to Hollywood, where he produced several hit films and helped to found the RKO studio, and to the liquor business, importing alcohol to the US both during Prohibition and after its repeal.

Joe and Rose were deeply ambitious for their children. They ached for them to excel, to win prizes, to be accepted, but the prejudice that had started at the Boston docks had travelled to the élite New York schools and not much had changed in this regard by the time Joe Jr and John F. Kennedy were of school age. As one contemporary commented, “To be an Irish Catholic was to be a real, real stigma – and when the other boys got mad at the Kennedys, they would resort to calling them Irish or Catholic.”8 Insults are part of the rough and tumble of boyhood shenanigans but it was more serious when the future president was refused access to certain schools favoured by the Brahmins. He was finally accepted by Choate, an exclusive boarding school in Connecticut, but found himself banned from joining many of the school’s prestigious clubs.

Young John Kennedy, nicknamed Jack by his family and close friends, was an average student who was fascinated by history and English, but not remotely so by mathematics or the sciences. Regularly unwell with a spastic colon, he lived his school and college days in the shadow of his irrespressible brother Joe, who was awarded the Harvard Trophy, a prize given to those who achieved both the best sporting and academic records. Jack wasn’t overly exercised by his brother’s achievements and made his way through Choate and then Harvard at his own pace, making lifelong friends, despite the occasional bout of racial prejudice. He was smartly groomed and well–spoken, but his sandy hair and blunt features gave him away as Irish before his surname was even mentioned, and the older, more puritanical Bostonian families still saw the Kennedys as nouveaux–riches upstarts.

As Joe Sr’s stock rose (metaphorically and otherwise), newspaper and magazine articles were written about his film and business interests, but time and time again they referred to the Kennedys as “Irish”, which was tiresome for both Rose and Joe Sr. On seeing the term used in a newpaper one morning, Joe is reported to have looked up and fumed “Goddam it! I was born in this country. My children were born in this country. What the hell does someone have to do to become an American?”9

Another family might have crumbled under such resentment and latent racism but it wasn’t the house style for the Kennedys, who soldiered on. Realising that money per se was not enough to win society’s acceptance, Joe Kennedy Sr pursued his career in politics, where respectability was attainable and money was always welcome. He pumped a fortune into Franklin D. Roosevelt’s successful presidential campaign of 1932 and for this, he was rewarded with the post of first Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, which Roosevelt established in 1934. For the 1936 campaign, Kennedy added to the small fortune he contributed by self–publishing a book entitled I’m for Roosevelt. All of this support was duly acknowledged and in 1937, as the world rumbled towards war, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, grandson of an immigrant cooper, was made American ambassador to the Court of St James. Kennedy was FDR’s man in Britain. In the space of a generation a tragic Irish family was slowly embodying the American Dream. The journey from Famine to Boston and now, the heart of the British diplomatic establishment was very quick but it was also vintage Kennedy.

A model of Irish Catholic achievement in America: a family portrait of the prosperous Kennedys, taken in 1938.

The ambassadorship was an exceptionally prestigious diplomatic position but in reality such posts are in the gift of the President and, to this day, they are often given to party grandees and important donors to party political funds. This appointment would prove to be a turning point in the story of the Kennedys and Ireland, as it was a year later, in 1938, that the head of the Kennedy clan met the Irish Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera. From here on, Irish–American relations would be transformed and all roads would lead to O’Connell Street, June 1963.