Читать книгу JFK in Ireland: Four Days that Changed a President - Ryan Tubridy - Страница 16

Making the first moves

ОглавлениеThe idea of any American president coming to Ireland was beyond the pale for people at the time. The very thought of an Irish–American Catholic becoming leader of the Free World had been unimaginable right up to election day in 1960. Here was Ireland,struggling to break free of the historical stranglehold that had gripped it for so long, an Ireland keen to move on from the de Valera years. It would bring glory by association for the country to welcome the man from the White House, a dynamic young politician from an Irish family who had reached the pinnacle of world power. For the Irish people, a visit from him would provide a shot of much–needed confidence on the world stage.

For all these reasons, from the moment John Fitzgerald Kennedy stepped through the pillared portico of the White House in January 1961, Lemass was keen to entice him over to Ireland, and he entrusted the job of achieving this to Ireland’s man in Washington, Dr Thomas J. Kiernan.

What began was effectively a dating game involving two interested parties who weren’t quite sure how to move things along despite a mutual attraction and a determination to make it work.

The job of Irish Ambassador to Washington has always been perceived as a plum post and has usually been manned by the brightest and best that the Irish diplomatic service has to offer. Such was the case with Thomas Kiernan, whose dispatches from the American capital are smart, wry and always perceptive. Born in the Dublin suburb of Rathmines, Kiernan was a career civil servant who in 1935 had been seconded to be director of Radio Éireann. He was married to the singer Delia Murphy, and while Kiernan was posted to the Vatican (1941–46) their semi–bohemian lifestyle in wartime Rome made them something of a talking point. Although strongly rumoured to become Ambassador to Britain, Kiernan in fact ended up running the embassies in Australia and Canada before being given the top job in Washington, a post he held from 1961 until 1964.37

The first time Kiernan met Kennedy was on 8 February 1961 at a function the President was hosting for upper echeclons of the diplomatic corps. It was an early evening affair, starting at 5pm and attended by Mrs Kennedy. The First Couple formally met and shook hands with all the heads of mission, Kiernan included. As was the way on these occasions, the guests sipped wine and made small talk while keeping one eye on what was happening in every other part of the room. In the diplomatic corps, everything, no matter how mundane, is an incident, real or imagined. Kiernan was doing just this when the President approached him. The two men chatted briefly but it was enough for them to make a connection. After those few minutes, Kiernan commented: “I realised that we were on the same wavelength, the same communication between us which was very important … he had Irish reactions and the Irish reactions helped me in understanding.”38

And with that, the diplomatic manoeuvres in the dark began. The plan? Get Kennedy, “our” other president, an Irishman, a Catholic, to Ireland. Things are never straightforward in the world of diplomacy, though. You can’t just issue an invitation when there’s a possibility that the other party might not be able to accept. Everything has to be handled slowly, step by step.

Despite Kennedy’s “Irish reactions”, the way he understood a wink and a nod without everything being stated openly, Kiernan felt let down by the quality of Ambassador the President decided to send to Ireland. At that diplomatic gathering, Kennedy had asked Kiernan who the current American Ambassador was. When Kiernan told him that it was Scott McLeod, Kennedy responded “Oh, he’s no good”, before adding “I’m going to send you a really good ambassador, an ambassador that will really represent America.”

Despite this statement, the next ambassador, Edward G. Stockdale, was of the same mould and dismissed by Kiernan as “a very, very poor type … [who had] very little intelligence … His I.Q. wasn’t very high. And that’s all we got.” Kiernan was disappointed and felt that “it showed President Kennedy’s lack of interest in Ireland at the time. He certainly had no intention of sending a good ambassador.” The truth is probably that the President’s choice of Stockdale was rooted in his contribution to party coffers, as was the normal practice, but it was a setback for Kiernan. Having a US ambassador in Dublin with whom he could work closely, in confidence, would have been a huge help, but Stockdale was not going to be that person.

The Irishman decided to play the long game. The Kiernan approach involved putting away the sledgehammer and going the softly, softly route. First things first for the Ambassador was not to play the Green Card, “There was no question of attempting to take advantage of the fact that his ancestors had come from Ireland. we bent backwards to avoid any kind of what I would regard as an intrusion.” Despite this, the Irish card made a natural apearance anyway. On 17 March, St Patrick’s Day, an Irish delegation gets annual access to the White House for what’s called the Shamrock Ceremony, during which the President is given a bowl of the famous Irish greenery. In recent years, the Taoiseach has made the trip but in 1961, the Ambassador did the honours and so, just a month after their first encounter, Dr Kiernan found himself back in the White House. In preparation for the ceremony, the wily diplomat made a call to the Office of Heraldry in Dublin and arranged for them to create a coat of arms that would bring together the O’Kennedy and the Fitzgerald clans. The two men met and Kiernan presented the bowl of shamrock and the coat of arms to the President, who was very appreciative. A rapport was slowly building beween them. It was a critical relationship in the story that was about to unfold.

Just three weeks later, on 11 April, the secretary at the Irish Department of External Affairs, C.C. Cremin, wrote to Kiernan noting that Kennedy was due to visit President de Gaulle in Paris at the end of May and adding “If the President and Mrs Kennedy should desire to come to Dublin they would, of course, be heartily welcome.” He went on to express his desire not to take advantage of Kennedy’s heritage or what the secretary described as the President’s “friendly sentiments for Ireland”. Cremin was at pains to stress that the Irish Government didn’t wish to embarrass Kennedy by issuing a formal invitation which he might in the circumstances feel it difficult to refuse and he urged Kiernan to take a discreet approach. Cremin finished this missive by mentioning a series of dates that wouldn’t be suitable because ministers would be otherwise occupied; these included early June (there was to be a visit from the German foreign minister), mid–June (Princess Grace of Monaco was bringing her husband to town) and late June (when there was to be a week of ceremonies, prayer and pageantry marking 1,500 years since the death of St Patrick).39

Kiernan decided not to force the issue. On 15 April the US army began the ill–fated Bay of Pigs invasion and it was obvious that President Kennedy’s thoughts would be elsewhere, so he didn’t issue an invitation on that occasion. Kiernan’s strategy was still, like Augustus’, festina lente, and in order to make haste slowly, the diplomat had to take advantage of every opportunity, no matter how tiny, to turn the President’s attention to things Irish. He didn’t have long to wait before another opportunity arose.

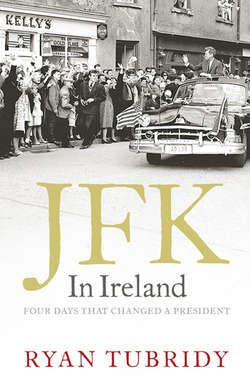

Courting Kennedy: Dr Thomas J. Kiernan, Irish Ambassador to the United States, with JFK after presenting him with a vase of shamrock for St Patrick’s Day. This photograph was taken in the Oval Office on 15 March 1963.

The people of Wexford, home to the original Kennedys, decided through their local political representatives that they would like to present the President and his wife with a christening cup for their baby son, John Jr, who had been born in November 1960. The seventeenth–century cup made its way across the Atlantic and into the hands of Dr Kiernan, who gave it to his wife, who in turn arranged to hand the gift to Jacqueline Kennedy at a small ceremony in the White House. President Kennedy had sent his apologies, citing meetings that day, but just as they were leaving home, the Kiernans’ phone rang. It was the White House. Kiernan was informed that the President would leave the meeting he was attending, so keen was he to attend the christening cup ceremony.

This was a most welcome diplomatic development. The Kiernans made their way briskly to Pennsylvania Avenue. Kiernan’s main concern that morning was that he hadn’t written a speech and couldn’t decide what to say. When he got to the podium, facing a battery of cameras and pressmen, he had to think on his feet. With Mrs Kennedy to his left and the President to his right, Kiernan had a lightbulb moment. He turned to Kennedy: “I asked him if, instead of a speech, I might recite a poem which had been [written] for my son the day he was born.” The President nodded and Kiernan proceeded.

… When the storms break for him

May the trees shake for him

Their blossoms down;

And in the night that he is troubled

May a friend wake for him

So that his time is doubled;

And at the end of all loving and love

May the Man above

Give him a crown.40

The President was moved. He whispered to Kiernan “I wish that was for me,” before making his way up to the microphone. As a reciprocal gift, the President presented to the people of Wexford a piece of the podium at which he had been inaugurated, to be delivered by Dr Kiernan.

It was little ceremonies like this one, and the increasingly relaxed nature of the President’s encounters with the Irish Ambassador, that helped build the bridge to Ireland.