Читать книгу JFK in Ireland: Four Days that Changed a President - Ryan Tubridy - Страница 15

CHAPTER THREE Wooing the President

ОглавлениеFor many years, Ireland had been effectively ruled by co–regents: the sorcerer, President Éamon de Valera, and the apprentice, Taoiseach Seán Lemass. Both men were products of Ireland’s Civil War but by the early 1960s it was apparent that the two were looking in different directions. De Valera was looking over his shoulder, obsessed with freeing Ireland from the last vestiges of British influence, while Lemass was looking at the road ahead, wondering about the possibilities beyond the stone walls and green fields of Ireland. The world was changing at an unprecedented pace and Ireland was faced with stark choices. It could sit back and let the opportunities pass by, or it could sit up and keep up.

Lemass had always had the more modern attitude of the two men. Less than two decades previously, as Minister for Industry and Commerce, he’d been behind a high–profile campaign to supply electricity to those living in the Irish countryside for the first time by building electrical poles across the country. He expressed his sense of hope and optimism through the prism of domestic bliss: “I hope to see the day that when a girl gets a proposal from a farmer she will enquire, not so much about the number of cows, but rather concerning the electrical appliances she will require before she gives her consent, including not merely electric light but a water heater, an electric clothes boiler, a vacuum cleaner and even a refrigerator.” Within ten years, a million electrical poles had sprung up and villagers and townspeople across the land held switching–on celebrations. Ireland was literally emerging from the Dark Ages.

Lemass was also concerned to try and halt the mass exodus of young people from the island. Economically, it was important for the country to start exporting products rather than people. In the early 1960s, there only 2.9 million citizens left, while a million people born in Ireland had taken up residence in England.34 Stroll along any platform on the London Underground and you can be sure that the hands of Irishmen built the walls. Look up at the magnificent buildings of the capital, or at some of the mundane housing estates scattered all around England, and you’ll find that in all likelihood, they were built by Irishmen who populated ghettos in North London suburbs such as Camden, Kilburn and Cricklewood.

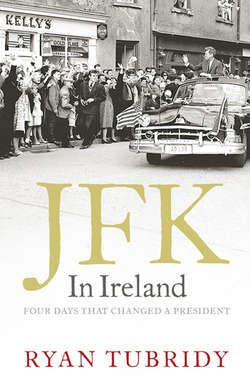

The sorcerer and the apprentice: Éamon de Valera (seated) and Seán Lemass at the ‘Military Tattoo Dance’ in Dublin, August 1945. Mrs Kathleen Lemass, Seán’s wife, sits beside de Valera.

There were as many Irish women as men in Britain, searching for a way to raise their family’s standard of living. Most of these emigrants ended up changing beds and preparing tea for middle–class English homeowners. The problem for the Irish government was that they didn’t have a lot to offer the next generation and something needed to be done to keep the nation alive.

In order to make Ireland breathe again, some of the repressive elements in daily life would have to be relaxed. The Church–State anschluss throttled cultural awakening, and the country’s ludicrous censorship laws had worsened in the middle years of the 20th century. In the early days of the Irish State, nearly a hundred books a year were banned from curious eyes, but by the early 1950s, the number of books being kept from the shelves numbered six hundred annually. When Irish book–lovers went to a bookshop or library and sought certain books by John Steinbeck, Graham Greene or Ernest Hemingway, they would find an empty space on the shelf. Thankfully, by the late 1950s there was a small but important shift as the number of books being censored began to drop and the fog of cultural repression slowly started to dissipate.

The proliferation of television aerials on chimneys from Dublin to Drogheda and the 1961 launch of State broadcaster RTÉ had a direct influence on Irish politics. Now people could see the faces of their politicians and make up their own minds about who they trusted and who made them suspicious. The days of the grey–suited older generation were coming to an end. Television would soon topple governments and lose wars and in Ireland, it would allow viewers to watch an Irish–American President address the Dáil, the first foreign head of state to visit since the attainment of independence.

The 1959 handover of the reins of power, when Lemass became Taoiseach, or Prime Minister, and de Valera took the symbolic role of President, was easily the most significant and important of the guard–changing exercises of the time. It signalled a real transition from the Old Guard to the New, mirroring the feeling in Washington, DC, that Kennedy’s election to the White House would inspire at the end of the following year. Also in 1959, James Dillon ascended to the top of the Fine Gael party while a year later, William Norton handed over to Brendan Corish in the Labour Party.

Within Lemass’s party, Fianna Fáil, there was major change too as a younger set assumed new positions that would lead to high office in the future. Young bucks like Patrick Hillery, Donogh O’Malley, Brian Lenihan and, of course, Charles Haughey jockeyed for attention, knowing full well that their time was coming.

But Lemass was the key figure of the era and modern historians are quick to recognise the Dubliner as the architect of modern Ireland.35 Lemass was perfectly placed to lead Ireland out of the rather gloomy period that marked the country’s nascent independence. Working alongside a visionary civil servant called T.K. Whitaker, a Secretary at the Department of Finance, Lemass drew up the Programme for Economic Expansion, a critical blueprint that dragged Ireland into the 1960s. Foreign investment became a keystone for the future. Agricultural pursuits shifted to massive exporting of beef and cattle. It became easier to access loans and invest in industry. Ireland was open for business. Having had the slowest rate of growth in Europe throughout the 1950s, Ireland surpassed itself by reaching annual growth of 4 per cent between 1958 and 1963 – higher than Britain and as good as most other countries in Europe. While Whitaker and his team should take much of the credit for this turnaround, his boss, Seán Lemass should share the plaudits as a gambler who wasn’t afraid to take risks.

As Irish writer and broadcaster Tim Pat Coogan wrote of Lemass: “He helped to solder past and present together, and suddenly to make politics something which gave a future meaning to the present.”36Eighteen years older than the American President, Lemass was by no means the Kennedy of his time but in a weary Ireland, it was probably enough that he wasn’t de Valera and at least his cabinet reflected the fact that there were people in Ireland under the age of sixty.