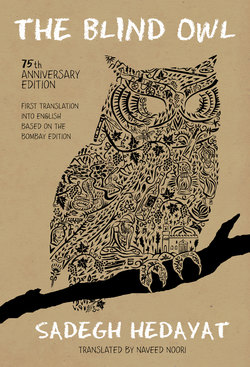

Читать книгу The Blind Owl (Authorized by The Sadegh Hedayat Foundation - First Translation into English Based on the Bombay Edition) - Sadegh Hedayat - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Textual Analysis

ОглавлениеDates of Publication and Available Texts

The first edition of The Blind Owl was published in 1936 (1315)1 in Bombay, India.2 Hedayat completed this work while studying the Pahlavi language in Bombay. On the first page of the book Hedayat wrote, “The printing and sale [of this work] in Iran is forbidden.” Knowing that publication of this book would never be allowed in Iran during the reign of Reza Shah, prior to his return to Iran Hedayat mimeographed 50 copies of the handwritten manuscript and sent them to friends and associates around the world. There is debate about when he actually wrote this book. As noted above, 1936 is the official date of publication. Some have argued that Hedayat wrote this before he left Paris in 1930; however, Katouzian and others have stated that based on the analysis of his work at the time, he could not have written this prior to 1934.1,2 M. F. Farzaneh argues that the second part of the work was influenced by his return to Iran, while Hedayat himself states that parts of it were changed when he was in India in 1936.3 Importantly, Hedayat does not appear to have revised this manuscript after the Bombay edition.4

Five years later, in 1941 (1320), with Reza Shah’s exile and the subsequent change in the political and social climate, part of The Blind Owl (in censored form) was published as a serial in Rooznameh-ye Iran.5 Apparently during the same year, the first typed version of The Blind Owl also appeared. I have been unable to locate any copies of either the serial or the first typed edition in any major library catalogs around the world. The first typed edition of 1941 may in fact have been considered the second edition as in the Amir Kabir and Javidan editions the first edition is always referred to as the Bombay edition. This second edition (or the first typed edition) is the edition published by Nashr-e Mazaheri. The autographed title page of M. F. Farzaneh’s copy can be seen in Ashnai ba Sadegh Hedayat.6 The Nashr-e Mazaheri edition was based on the censored Rooznameh-ye Iran version, but apparently with some changes.7 There is one unsubstantiated account of this being the definitive edition, claiming Hedayat personally worked with the staff of Rooznameh-ye Iran on this edition; however, this comes from a brief article based on a phone conversation with a “friend” of Hedayat.1 This friend has never been identified, and this claim has been rejected by scholars such as Baharloo, as well as Hassan Qaemian, who worked at Rooznameh-ye Iran at the time.2 As mentioned before, Hedayat does not appear to have revised this manuscript after 1936. Both the Hedayat Foundation and M. F. Farzaneh (who owns both the first and second editions) consider the Bombay edition to be the definitive edition, and both have published this edition.3,4

After the Nashr-e Mazaheri edition, The Blind Owl was not reprinted for about 10 years. In Hedayat’s letters to Shahid-Noorai prior to Hedayat’s final trip to France, there is no mention of a reprint of The Blind Owl, whereas the two do discuss new editions and reprints of other works, as well as a failed effort on the part of a publisher to publish his entire catalogue.5 M. F. Farzaneh’s account of this time and a publisher’s failed bid to acquire the rights to all of Hedayat’s works also matches this.6 However, in a letter to Shahid-Noorai, Hedayat mentions the translation of The Blind Owl into French by Orientalist and diplomat Roger Lescot whom Hedayat had met in Tehran. The translation appears to have been completed by 1948 but its publication was delayed when the intended publisher (Grasset) ran into difficulties.7 Upon Hedayat’s departure for France, he had put Manoochehr Kolbadi in charge of publishing his works.1 It is likely that he reached an agreement with Entesharat-e Amir Kabir once Hedayat was in France, or after his death. One source states that the first Amir Kabir edition was published in 1950.2 It is possible that this was published when Hedayat was in France. However, it is more likely that The Blind Owl was not re-introduced in Iran until after Hedayat’s death.

After Hedayat’s suicide in 1951, the fourth edition was published by Amir Kabir, and new editions of this work were published by Amir Kabir for the next several decades. This edition was said to have been edited and compiled by Hedayat’s father and Bozorg Alavi.3 This fourth fourth edition is the earliest typed edition this author could find and examine,4 and is available in several of the major libraries around the world (Edinburgh University, Harvard University, University of London, University of Manchester, University of Michigan, and the University of Pennsylvania). In addition to the fourth edition, I have closely examined the eighth Amir Kabir edition,5 as well as the Javidan Javidan edition.6 Thus, there is the problem of the third edition. Was this published by Amir Kabir right before Hedayat’s death (based on the Nashr-e Mazaheri), or was it published after his death (the edition compiled by Hedayat’s father and Bozorg Alavi)? Or is the third edition actually the Nashr-e Mazaheri edition, and the second was considered the Rooznameh-ye Iran serialized version? In either case, what we have remaining today are the first and fourth editions (the former handwritten by Hedayat and largely unavailable until M. F. Farzaneh’s reprint in 1994, and the latter which is the source of most subsequent Persian editions and foreign translations).

The first translation of this work was by Roger Lescot. It was published in book form in France in 1953.1 However the translation into French, which appears to have been completed by 1948, was first published in serial form in Egypt in the journal La revue du Caire in 1952. Although I am not proficient in French, it seems that Lescot had access to the Bombay edition and that the translation is either based entirely on that edition, or possibly a combination of the Bombay and Nashr-e Mazaheri editions. In all existing Persian editions, from at least the fourth edition onwards, the first sentence is also the entire first paragraph, but this is not the case in the Bombay edition or Lescot’s. Also, Lescot’s edition has the reproduction of two of Hedayat’s drawings that are found in the Bombay edition, but these are not seen in the existing Persian editions. In addition, in the very first section of Lescot’s translation, the paragraph structure differs in one way from the Bombay edition (and in this respect is similar to the fourth Amir Kabir edition). The first section the Bombay edition has five paragraphs, Lescot’s translation six paragraphs, and Amir Kabir (and Costello’s translation) seven paragraphs. Thus, Lescot may have used more than just the Bombay edition for the translation.

The first English-language translation, published in 1957, was by Desmond Patrick Costello.2 This author has examined that edition. In the Costello version there is no introduction by the translator that identifies the source text. It has been suggested by some that the English translation was based on Lescot’s French translation. Costello first studied Persian around the age of 40 while working at a diplomatic mission in Paris (1950-1955), and it was during this time that he translated The Blind Owl into English.3 Thus, while in Paris he might have been introduced to Hedayat by his Persian tutor but it is equally likely that he would have been familiar with Lescot’s acclaimed translation which was published in 1953 (when Costello was in Paris).

Costello was a linguist with a working knowledge of at least nine languages; however, it is difficult to imagine him mastering Persian to the point of translating a book while also serving full-time as a diplomat and continuing the study of other languages such as French and Russian. Based on formatting alone, Lescot’s translation was likely based on a pre-third/fourth edition version, while Costello’s was definitely based on a post-third/fourth edition version. It remains a possibility that Costello used both Hedayat’s Persian and Lescot’s French versions for the English translation; however, this would require detailed analysis by someone fluent in English, French, and Persian. Regardless of this, as has been noted before and will be demonstrated below, Costello’s version differs substantially from Hedayat’s original text and is a classic example of “domestication” in translation.1

Textual Analysis

All Persian typed editions since 1951 and the English translations share a common source which is not the Bombay edition. I contend that during the typesetting of an early edition (the third or fourth Persian edition) a multitude of errors was introduced that can be easily traced through the later editions. There have been attempts to correct some of these. The first was the 1977 Javidan publication of The Blind Owl;2 however, this still suffers from the same basic problems and although this edition corrected some of the mistakes of the Amir Kabir editions, it introduced other errors into the text. After the 1979 revolution, publication of The Blind Owl within Iran was allowed for only a very short time. The 2004 edition published by Entesharat-e Sadegh Hedayat again attempted to correct the problems of earlier editions, though there are still some fundamental differences with the Bombay edition, especially with punctuation and use of the dash.1 Finally, in 2010 the Iranian Burnt Book Foundation (in conjunction with the Sadegh Hedayat Foundation) published a typed Persian edition alongside a reproduction of the handwritten Bombay edition.2 This typed edition comes closest to the Bombay edition and has corrected most of the problems of earlier editions, though minor discrepancies can still be found. Hillmann has stated that no authoritative edition of The Blind Owl in Persian exists;3 however, this statement was made before the first reprint of the Bombay edition in 1994. As I will demonstrate below, the handwritten Bombay edition should be considered the definitive edition, if not the major source for a definitive edition.

In comparing four consecutive pages of the Javidan edition (pages 19-22) to the Bombay edition, we find a multitude of differences. I counted 46 differences in these four pages. If we extrapolate this to the entire work, we have approximately 909 instances of differences between the two editions. In the same text for the early Amir Kabir editions, I found 54 differences (approximately 1067 instances of differences between the texts). These differences include:

1) Typographical errors.

2) Changes in verb tense.

3) Addition, omission, or substitution of single words.

4) Changes in punctuation (change of a period, dash, or comma to any of the others, or omission/addition of punctuation).

5) Changes in formatting (where a paragraph starts and ends).

In the section below, we will examine some of these in more detail. I have underlined the changes in the Amir Kabir edition corresponding to changes from the Bombay edition (asterisks are placed next to the source line in the Bombay edition).

1) Page 11 of the Amir Kabir edition, corresponding to page 8 of the Bombay edition. An ill-placed comma after aftab breaks up the sentence and confuses its meaning (this error was fixed in the Javidan edition).

2) Page 18 of the Amir Kabir edition, corresponding to page 16 of the Bombay edition: The word alam-e barzakh has been changed to alam-e mesal. There are also some punctuation changes and one word omission (va).

3) Page 25 of the Amir Kabir edition corresponding to page 24 of the Bombay edition: verb tense changed from keshide-and in the Bombay to keshide boodand in the Amir Kabir.

4) Page 25 of the Amir Kabir edition corresponding to page 25 of the Bombay edition: verb tense changed from nadasht in the Bombay to nadarad in the Amir Kabir. The Bombay has verb tense consistency (nadashtam/nadasht) that is lacking in the Amir Kabir edition (nadashtam/nadard). In addition, the dash at the end of the word has been changed to a period and the paragraph has ended (in the Bombay there is a dash with a continuation of the sentence/paragraph).

5) Page 27 of the Amir Kabir edition corresponding to page 27 of the Bombay edition: Two words amad va in the Bombay changed to one word amade with a verb tense change in the Amir Kabir. There is also a change of a comma to a period here.

6) Page 30 of the Amir Kabir edition corresponding to page 31 in the Bombay edition. The insertion of the period after boodam in the Amir Kabir edition cuts the sentence midstream. This has the effect that the new sentence, starting with hala, changes the narration from the past abruptly to the present tense, which is incongruous with the rest of the first part.

In addition to the changes noted above, all Persian editions and major translations (including Lescot’s) do not set off the second part of the story in italics. In the Bombay edition, every paragraph in the second section is set off with quotation marks, signifying a narrative within a narrative. This important omission clearly can affect the entire way in which The Blind Owl is interpreted, and may be one reason for the disparate analyses of the work.1 Below is an example of how Hedayat set off this part (see arrows).

The various changes noted above can be traced through the various translations and editions. One easy way to tell this is by examining the first sentence of the book. In the Amir Kabir and Javidan editions, as well as Costello’s translation, this sentence is an entire paragraph (that is a new paragraph starts with the next sentence). However, in the Bombay edition and Lescot’s translation, the first sentence is part of a much longer paragraph.

Other formatting changes like this one can be easily compared between the editions. From this alone it is clear that neither Costello nor Bashiri used the Bombay edition for their English translations, but used an edition derived from the Amir Kabir editions (post third/fourth).