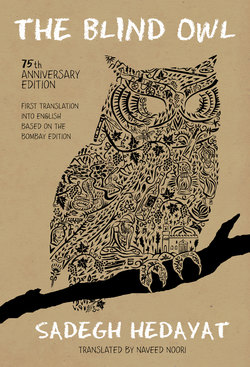

Читать книгу The Blind Owl (Authorized by The Sadegh Hedayat Foundation - First Translation into English Based on the Bombay Edition) - Sadegh Hedayat - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Domestication versus Foreignization in Translation

ОглавлениеBecause of inherent differences between languages (meanings of words, sentence structure, etc.) a literary translation can never duplicate the original; however, it is the translator’s task to strive for this. Translators constantly wage war and peace between fluency and fidelity, where the former represents the ease of reading (or “flow”) in the target language, whereas the latter represents the accuracy in conveying the author’s meaning from the source language.

Schleiermacher and Venuti have argued against the centuries-old tradition of emphasis on fluency.3 They present this within the context of domestication versus foreignization of translation. Domestication occurs when fluency is strived for at all costs, and the culture, words, and even meaning of the text are made to conform to the target language (the analogy is that the work travels to the source country and assimilates or is domesticated). Foreignization is the opposite, where an effort is made to preserve the source language and culture by use of language or techniques that may be unfamiliar to the reader (in this case it is the reader that travels to a foreign land to experience the work). Venuti writes:

A translated text, whether prose or poetry, fiction or nonfiction, is judged acceptable by most publishers, reviewers, and readers when it reads fluently, when the absence of any linguistic or stylistic peculiarities makes it seem transparent, giving the appearance that it reflects the foreign writer’s personality or intention or the essential meaning of the foreign text—the appearance, in other words, that the translation is not in fact a translation, but the “original”. . . . By producing the illusion of transparency, a fluent translation masquerades as true semantic equivalence when it in fact inscribes the foreign text with a partial interpretation, partial to English-language values, reducing if not simply excluding the very difference that translation is called on to convey.

Domestication of the Blind Owl

As the Costello version is the most popular, widely available, and considered the gold standard, I will focus this discussion mostly on this work. Costello’s translation is entirely fluent and reads well; however, in doing so, the narrator’s voice has changed, and the text has become domesticated. This was one of the main reasons I decided to undertake this project. There are many instances where the subtleties of Hedayat’s written word have been overlooked for ease of transitions. Below I will cite a few examples of this.

On page 11 of the Bombay edition Hedayat writes, “hameye mardom be biroone shahr hojoom avorde boodand.” Costello has translated this as “Everyone had gone out to the country.” While this is correct translation in terms of the action, it only manages to push the narrative from Point A to Point B. By ignoring the verb “hojoom avordan,” Costello effaces the sarcastic tone of the narrator, who has consciously chosen to stay home that day and who is actually making fun of the masses. “Hojoom avordan” in the context used implies a military attack, and thus is difficult to translate, which may be why Costello chose to ignore it. Bashiri chose to solve the problem in this way, “Everybody had rushed to the countryside.” Bashiri attempted to keep the sarcastic tone, but the use of the verb “to rush” could also be taken as the people were “hurrying.” The solution chosen in the current translation was to keep the tone while introducing a different kind of attack: “The entire populace had swooped down upon the countryside—” While the translations by Bashiri and myself can be criticized in a number of ways, they provide good examples of the difference between domestication and foreignization. For a detailed discussion of Costello’s domestication of The Blind Owl, I refer the reader to an article by Ghazanfari and Sarani.1

One major way in which this translation differs from previous ones is treatment of the dash, which can be viewed in the context of domestication. In the typesetting, the dash was oftentimes replaced by a period, comma, or semicolon. This was done to an even greater degree when Costello translated from Persian to English. While in some instances a substitution (dash for another form) can be made without a change in the meaning of an individual sentence, we must keep in mind that Hedayat chose the dash over and over again, instead of these other, more common, forms of punctuation. The dash is different from the period, comma, and semicolon in that it has additional attributes: the dash can represent emotion, haste, or the breaking off of a thought.

The narrator of The Blind Owl is disturbed and one imagines him scribbling furiously away. One way in which Hedayat shows this emotion and haste is with the repetitive use of the dash. The narrator in Costello’s version is much calmer and under control, and I believe one reason is the elimination of the dashes brought on by the typesetting and translation.

Method of the Current Translation

In this translation, I consciously sought to bring the English reader into the world of Boof-e koor. My method was to begin with a foreignized bias to preserve each sentence and its meaning. Next, repetitive proofreading and editing were undertaken to improve the flow and bring the text closer to the center. The result is the retention of untranslatable Persian words (with footnotes), the use of atypical English words and phrases to convey the Persian, and the use of the dash as it appears in the Bombay edition. Of course the danger with foreignization is that it challenges the reader to leave behind the confines of their familiar language and home to travel to a different land. In this edition I have tried to balance the two, while not fearing the effect of foreignization.

As noted above, I believe the use of the dash to be part of the discussion between domestication and foreignization in translation. In the Bombay edition, the narrator is more agitated, and I have tried to preserve this mood by means of the dashes. Although readers may initially be put off by this, I believe that, as with any particular form of punctuation that is used repetitively as a literary device, they will get used to it and that this effect will add to the experience, as it does in the Persian.

In other parts of this work I have tried to preserve the essence of Hedayat’s Blind Owl by using atypical English words or phrases. Kabood is a key word scattered throughout the text. Costello translated this word as “blue,” but this fails to convey its more complex meanings. In Persian this word can be defined as a color or a bruise, and in the context of the work it is closer to the latter. In the book Tavil-e Boof-e koor,1 there is an interesting discussion about the pairing of niloofar-e kabood. Strictly speaking, niloofar in Persian is a morning glory, while niloofar-e abi is a lotus. Hedayat apparently had translated the lotus flower from French into niloofar-e sefid or a “white” niloofar in Persian. This takes on additional significance because the lotus was a symbol of Achaemenid Persia seen in the bas reliefs at Parseh (Perspolis). By turning white (sefid) into dark (kabood), and coupling this with a symbol of ancient Iran, the “bruise” of kabood had particular importance for Hedayat. However, in terms of translation, the use of “lotus” for niloofar produces difficulties. Lotuses are water plants and we have clear references in the work to niloofars growing in dirt. While one can argue that certain parts of the work could be somewhat surreal in nature, the niloofars in dirt also occur in sections which are not surreal. I believe that the use of niloofar is complex, and that Hedayat likely had the lotus in mind as a symbol. For consistency, I have chosen “morning glory” for niloofar while making the reader aware of the additional symbolism.

One of the keys to understanding Hedayat and Hedayat’s Blind Owl is the relationship between pre-Islamic and Islamic Iran, the relevance of which has been lost in the two existing English translations. Part of this has to do with not setting off the second part of the book. Favoring fluency over meaning in translation of key words (domestication) has also contributed to this. As Ghiyasi has noted, the “bruised lotus” is an important symbol (which a “blue” flower could never convey). Likewise, I would like to point out the usage of pre-Islamic and Islamic coins in the two different sections signifying the two different time periods. In this translation I have tried to preserve this aspect, providing footnotes with explanations to serve as a starting point for the interested reader. For a detailed description and discussion of the symbols of the vase, the ethereal girl, city of Rey and the Suren River, and their relationship to Hedayat’s philosophy and his earlier work Parvin, Sassan’s Daughter, I refer the reader to Houra Yavari’s essay entitled “Sadegh Hedayat and a modernist view of history.”1 In addition, M. F. Farzaneh’s Ashnai ba Sadegh Hedayat provides details of Hedayat’s personal life that were used as inspiration for certain passages (the breaking of the vase, the numbers two and four, etc.), as well as an interpretation of The Blind Owl as Hedayat’s Manifesto.2

Translator’s Style and Conclusion

Beyond the theory and methods behind translation, each translator brings their own voice to a translation. Although some may try, as Venuti states, to remain “invisible,” in the act of choosing one word over another, over and over again, different styles and voices are inevitably revealed. And this provides another means of distinguishing various translations. Below is the first sentence of The Blind Owl translated by three different persons. In this first sentence alone we see three completely different results. Each of these translations reveals Boof-e koor in a different way. It is my hope that this and other translations of Hedayat’s works will spur a renewed interest in his works.

Costello: “There are sores which slowly erode the mind in solitude like a kind of canker.”

Bashiri: “In life there are certain sores that, like a canker, gnaw at the soul in solitude and diminish it.”

Noori: “In life there are wounds that, like leprosy, silently scrape at and consume the soul, in solitude—”

Naveed Noori

Samangan

2011

1 Dates are given first in the Gregorian calendar, followed by the Iranian calendar.

2 All references to the Bombay edition in this introduction are based on the following edition which is a reproduction of one of the original 50 mimeographed copies (in the possession of M. F. Farzaneh): S. Hedayat, Matn-e kamel-e Boof-e koor va Zende be goor [The complete Blind Owl and Buried Alive] (Spanga, Sweden: Nashr-e Baran, 1994).

1 H. Katouzian, Boof-e koor-e Hedayat [Hedayat’s Blind Owl] (Tehran: Nashr-e Markaz, 1998/1377).

2 M. T. Ghiyasi, Tavil-e Boof-e koor [Interpretation of the Blind Owl] (Tehran: Entesharat-e Niloofar, 2003 / 1381), 51-53.

3 M. F. Farzaneh, Ashnai ba Sadegh Hedayat [Becoming acquainted with Sadegh Hedayat] (Paris: printed by author, 1988 / 1367), 185.

4 Personal communication via Jahangir Hedayat (Hedayat Foundation).

5 Rooznameh-ye Iran (ed. Zainalabedin Rahnama) was a daily that began publication (dor-e jadid) on November 19, 1941 / 28 Aban 1320.

6 M. F. Farzaneh, Ashnai ba Sadegh Hedayat [Becoming acquainted with Sadegh Hedayat] (Paris: published by author, 1988 / 1367).

7 Ibid., 186.

1 M. Baharloo, Nameh´ha-ye Sadegh Hedayat [Sadegh Hedayat’s letters] ([Tehran:] Nashr-e Oja, 1995 / 1374), 316.

2 Ibid.

3 S. Hedayat, Matn-e kamel-e Boof-e koor va Zende be goor [The complete Blind Owl and Buried Alive] (Spanga, Sweden: Nashr-e Baran, 1994).

4 S. Hedayat, J. Hedayat, and S. Vaseghi, Majmoo’e-ye asar-e Sadegh Hedayat, jeld-e chaharom, Boof-e koor [The complete works of Sadegh Hedayat, vol. 4, The Blind Owl] (Sweden: Iranian Burnt Book Foundation, 2010).

5 S. Hedayat, Hashtad o do nameh be Hassan Chahid-Nourai [82 letters to Hassan Shahid-Noorai], 2nd ed. (Vincennes, France: Cesmandaz, 2000 / winter 1379), 136, 138, 218, 219.

6 M. F. Farzaneh, Ashnai ba Sadegh Hedayat [Becoming acquainted with Sadegh Hedayat] (Paris: published by author, 1988 / 1367), 232.

7 S. Hedayat, Hashtad o do name be Hassan Chahid-Nourai [82 letters to Hassan Shahid-Noorai], 2nd ed. (Vincennes, France: Cesmandaz, 2000 / winter 1379), 155.

1 M. Baharloo, Nameh´ha-ye Sadegh Hedayat [Sadegh Hedayat’s letters] ([Tehran:] Nashr-e Oja, 1995 / 1374), 279.

2 N. Habibi-Azad, Ketabshenasi-e Sadegh Hedayat [The bibliography of Sadegh Hedayat] ([Tehran:] Nashr-e Qatre, 2007 / 1386), 33.

3 M. Baharloo, Nameh´ha-ye Sadegh Hedayat [Sadegh Hedayat’s letters] ([Tehran:] Nashr-e Oja, 1995 / 1374), 317.

4 S. Hedayat, Boof-e koor [The Blind Owl], 4th ed. (Amir Kabir) (Tehran: Nashr-e Sina, 1952 / 1331).

5 S. Hedayat, Boof-e koor [The Blind Owl], 8th ed. (Amir Kabir) (Tehran: Entesharat-e Amir Kabir, 1959 / 1338).

6 S. Hedayat, Boof-e koor [The Blind Owl], Javidan edition (Tehran: Chapkhane-ye Mohammad Hassan Elmi, 1977 / 2536).

1 S. Hedayat, La chouette aveugle, trans. by R. Lescot (1953; repr., Paris: José Corti, 1969).

2 S. Hedayat, The Blind Owl, trans. by D. P. Costello (New York: Grove, 1957).

3 J. McNeish, The Sixth Man: The Extraordinary Life of Paddy Costello (Auckland: Vintage, 2007), 173, 279.

1 M. Ghazanfari and A. Sarani, “The Manifestation of Ideology in a Literary Translation,” Orientalia Suecana 58 (2009): 25-39.

2 S. Hedayat, Boof-e koor [The Blind Owl], Javidan edition (Tehran: Chapkhane-ye Mohammad Hassan Elmi, 1977 / 2536).

1 S. Hedayat, Boof-e koor [The Blind Owl] (Tehran: Entesharat-e Sadegh Hedayat, 2004 / 1383).

2 S. Hedayat, J. Hedayat, and S. Vaseghi, Majmoo’e-ye asar-e Sadegh Hedayat, jeld-e chaharom, Boof-e koor [The complete works of Sadegh Hedayat, vol. 4, The Blind Owl] (Sweden: Iranian Burnt Book Foundation, 2010).

3 M. C. Hillmann, “Buf-e kur,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica, ed. E. Yarshater, Article published December 15, 1989. Online edition accessed at www.iranica.com on May 16, 2010.

1 For further discussion regarding the various interpretations of The Blind Owl please refer to chapter 8 of Sadeq Hedayat: the Life and Literature of an Iranian Author by Homa Katouzian (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2002) and Ashnai ba Sadegh Hedayat by M. F. Farzaneh.

1 F. Bowers, “Some Principles for Scholarly Editions of Nineteenth-Century American Authors,” Studies in Bibliography 17, no. 1 [1964]: 226.

1 S. Hedayat, Matn-e kamel-e Boof-e koor va Zende be goor [The complete Blind Owl and Buried Alive] (Spanga, Sweden: Nashr-e Baran, 1994).

2 S. Hedayat, J. Hedayat, and S. Vaseghi, Majmoo’e-ye asar-e Sadegh Hedayat, jeld-e chaharom, Boof-e koor [The complete works of Sadegh Hedayat, vol. 4, The Blind Owl] (Sweden: Iranian Burnt Book Foundation, 2010).

3 L. Venuti, The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (London and New York: Routledge, 2002), 1, 21.

1 M. Ghazanfari and A. Sarani, “The Manifestation of Ideology in a Literary Translation,” Orientalia Suecana 58 (2009): 25-39.

1 M. T. Ghiyasi, Tavil-e Boof-e koor [Interpretation of the Blind Owl] (Tehran: Entesharat-e Niloofar, 2003 / 1381), 52.

1 H. Yavari, Dastan-e farsi va sargozasht-e modernite dar Iran [The Persian novel and the story of modernity in Iran] ([Tehran:] Nashr-e Sokhan, 2009 / 1388).

2 M. F. Farzaneh, Ashnai ba Sadegh Hedayat [Becoming acquainted with Sadegh Hedayat] (Paris: published by author, 1988 / 1367), 347.