Читать книгу Killing Karoline - Sara-Jayne King - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 5 Unhappy birthday

Оглавление1 August 1982

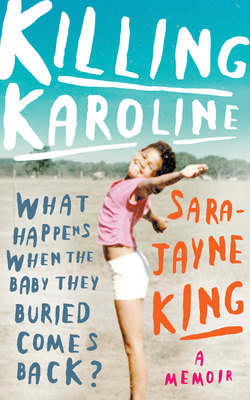

‘Am two today!’ I awkwardly hold up two pudgy fingers. ‘That’s this many!’

The mummy at the door, who is not mine, looks amused. I don’t understand why.

Because I’m two, other small people – assumed, by virtue of our similar ages, to be my friends – have been invited to my birthday party at our house in the tiny, green-belt village of Tandridge in the South of England. People are here to see me being two and, best of all, give me things. Presents. I have presence of my own already, holding court at the front door, welcoming my guests and their tag-along grown-ups.

It is summer and my brown skin, browner than usual, having been touched by the sun, is the colour of moderately strong coffee and makes my cherubic arms and legs even more biteable than usual. I am the only brown little girl at my nursery school – in fact the only brown child. Adam is the only brown boy at his school of seventy-five pupils. We both stand out a lot. We say ‘brown’ because that’s what colour our skin is. We say ‘half-caste’ because that is what other people say. We also say ‘gollywog’ because Robertson’s says it on their jam jars and we don’t know any better.

My hair is a short, but unruly mass of what, according to some, looks like wire wool. I have on a blue summer dress, covered with delicate white-and-yellow stitching that is supposed to look like little daisies. The dress has been made, by hand, by Granny from a pattern she found in a magazine. She does that a lot, Granny. She makes me clothes, because she is from the war and in the war you had to make do and sometimes there weren’t even bananas. The pictures in the magazine show you how to make your own dress, where to cut and where to sew, using your own material. Making your own is better, because then whatever you are making will fit perfectly. Fitting is important. Sometimes things fit. They are snug and comfortable; they become a part of us. But sometimes even things that are new do not mould to us and they occupy an awkward space. In us, they do not find a home or footrest. They twitch uneasily, arching their backs against our outstretched arms and open chests. When things don’t fit, we panic. Terrified of consequences, unfinished pictures, spilling over the edges and blurred lines.

But when things do fit, it is a moment of deliverance as each atom clicks into its pre-ordained position, finding its way effortlessly, gently, like fingers along a collarbone, like a journey back home. Ultimately, we decide whether something fits or not. We cannot force or manipulate, but we can stroke, encourage, exhale and make space. Sometimes, clothes that you see in the shop, clothes made by someone else, don’t fit properly and they make you uncomfortable. Although the end result is the same, it’s still better to make your own from scratch, rather than taking something off the rack that you might not like as much.

Because my birthday falls in August, often the hottest month of the year in England, I spend most of my life under the logical impression that I was born in the summer. It becomes a fundamental belief, something I hold on to as a type of validation of who I am, who I always was and who I will always be. The concept grounds me somehow, providing a context for my existence where none, save for a few scribbled notes on a social worker’s pad, exists. In my child’s imagination I create a make-believe memory of my biological mother in the last few weeks of her pregnancy, heavy and sweating, constantly fanning herself against the punishing sun and standing in a garden on a sticky summer evening, belly swollen, desperate for respite from the heat. It is not until I am approaching my thirty-third birthday, and have returned to live in South Africa, the country of my birth, that it strikes me that I am not in fact a summer baby. August, in South Africa, signals the beginning of the end of winter. The realisation hits me one frigid Johannesburg morning in July while preparing to leave for work, wrapping myself up against the crisp pre-dawn bite and watching my breath create misty ghosts in the morning air. Suddenly, something I have held on to my whole life is torn asunder. Although it is not the first time I am forced to reframe my beliefs of how I came to be in the world, it unseats and unsettles me for a long time. Adoption, I have found, is like that. It creates gaps for assumptions, false imaginings and, ultimately, disappointments.

As a child, my birthday becomes synonymous with end of the school summer term, coordinating my birthday party around friends’ family holidays and being able to swim in Granny’s pool again. I come to equate other things with my birthday too. The annual return of three glorious hours of children’s television programming every morning for two months during the summer. Why Don’t You? is a real favourite. ‘Why don’t you switch off your TV set and do something less boring instead!’ A strange choice of lyrics for the theme tune to a children’s TV show, but we stay glued to the box nonetheless, often for hours afterwards until, one day in complete exasperation at our continued inertia, my mother removes the fuse from the television plug, locks it away in her bedroom and drives off to work, leaving us staring and mute at a purely ornamental television set. My brother Adam becomes my absolute hero that day when he deftly removes the fuse from the kitchen kettle, inserts it in the TV plug and lights up the fool’s lantern again before my mother has even made it out of the driveway.

Other things that signal the advent of my birthday are getting all sweaty and sticky when strawberry picking (although the magic is taken out of it somewhat the day I realise we must pay for what we have picked, and that we are not simply the beneficiaries of an altruistic fruit magnate) and the sickly sweet smell of rape seed that invades the fields near our house as a shock of bright yellow. Summer is now, and was for me then, my favourite season. Winter feeds my melancholy and coaxes my black dog out of hibernation.

I soon learn that the thing about birthdays is that you are supposed to be happy. Those are just the rules. You must be happy and you must smile and be happy for being happy and, more than anything, be happy for being born. From a young age I understand this notion and do my best to play along. But, despite all the happy and the smiling and the trick candles that relight (even when you think you’ve blown them out for good), I am always plagued by feelings of sadness and despair when my birthday comes around. It becomes 24 hours of unmet expectations and angst and a historical certainty that at some point during the day I will cry. I find a place, somewhere my aching and I can be alone, and I weep. I then feel ashamed by my tears, and my inside voice gives me a brusque talking to and I turn the smile back up to ten again, inhale and blow out the damn candles once and for all. Because actually, for me, having been given up for adoption at just a few weeks old, my birthday doesn’t represent happiness or joy or celebration; it represents loss, rejection and abandonment at the most crucial moment of my life. Of course, at only a couple of months old, I would have had no words to express those feelings, and even later, when the words are there, the deep and profound sadness I feel will be compounded by a sense of shame. Shame, that to the rest of the world I am showing myself to be ‘ungrateful’ for the good fortune that has been bestowed upon me by being so selflessly ‘taken in’ by my adoptive parents. Because, how can one who has been rejected by their mother, their own mother, as a babe in arms, be anything other than the most unlovable, unworthy, unwanted wretch to ever take breath?

As a teen and later an adult, that primal sense of loss I could not put a name to would manifest in my being moody and distant. I would often check out emotionally or take myself away when my birthday came around so as not to create another opportunity to be abandoned. It took me years to understand why I felt so detached. If I did celebrate I would go overboard, arranging week-long birthday celebrations, as though to validate my existence somehow. ‘She may not have wanted me then, but look how many people love me now,’ I would try to tell myself. I fluctuated between wanting to disappear completely and feeling compelled to scream, ‘It’s my day! I’m here! I’m here! SEE ME!’ My emotions leapt from excitement to dread to apathy to misery, and each year would be consumed by a desperate expectation that this year would be different. This year there would be no tears, this year I would be spared the feeling, the one I could not name or explain, and maybe even this year someone might ask me, ‘How are you feeling?’ and give me permission to speak my unspeakable truth.

To this day, every year, I think about Kris and the questions rise again. Is she thinking about me? Does she remember? Is she too battling an unspoken grief, or does the day pass like any other? The wondering almost chokes me.

Despite having existed for a mere twenty-four months, I feel as if I have always been here. I know I’m not the oldest but I’m definitely not the youngest either. Babies are brand new. I’ve been here for much, much longer than babies. I’ve even held a baby so I must be a much bigger person than a baby. Two is definitely significant. When I think now of how short a time two years actually is, it makes me think. Could she, Kris, really have gotten over such a momentous episode in her life, our lives, in just two quick-as-a-flash years? Some cellphone contracts are longer than that and when the time comes to upgrade, bow out or look for another provider, I’m always, without fail, stunned at how quickly the time has gone. Surely the maternal pull must be stauncher than the small print of a cellphone contract?

And now, at my party, the mummy at the front door hands me a secret wrapped in shiny paper and a card I’m less interested in. She walks past me and into the house with a mini-version of herself.

Both mother and daughter have wide, dark eyes, gingerbread freckles dusted over the nose and a small, tight, uneven mouth that looks like a mistake. The bottom lip is disproportionately full compared to the top one, as if it has been given the lion’s share of plumpness. There is no denying the little girl and the woman are related. It’s like simultaneously looking back in time and also forward by way of a crystal ball; they are in essence the same, forever unchangeably linked, in life, in death, in distance.

It’s something I will always be fascinated by. Familial likeness.

I don’t look like Mummy or Daddy, or Granny or Grandpa, or Yorkshire Granny. I do look like Adam because we are both brown. Adam has long eyelashes, though – that’s what everyone says. When I’m older and at first school, Adam will sometimes come to fetch me from my class and we will have to go to the dining hall and sit on the gym bench and have our pictures taken. All brothers and sisters have to do it. There’ll be a big white umbrella and a bright light and Adam will sit behind me and the lady will say, ‘Say cheese,’ and I will wonder why, but say it anyway and then we’ll go back to class and I’ll be disappointed that it’s all over, so I’ll walk back really slowly, take my seat and begin fluently reciting my five-times table. When the pictures come back, there will be much excitement in class. When they are handed out, I see my and my brother’s faces looking out from behind the protective cellophane. Adam’s symmetrical, even toned and pretty, mine gap-toothed, mono-browed, eyes far too large for the face. I will shuffle through each of the various pictures, large, small, smaller, hoping – despite knowing they are all the same – that I will find one where I look … non-ugly. The year Adam leaves for middle school comes as something of a relief for me. I am still ugly, but not by comparison.

Downstairs Mummy is in the kitchen handing out birthday cake wrapped in pink napkins with stick-figure little girls with blonde straw-like hair on them. The little girls are holding hands. Mummy is dragging on a Peter Stuyvesant and wearing her apron with the Manneken Pis on the front. Daddy bought it for her on one of his business trips to Brussels where they speak differently.

I do and will always find the smell of Mummy’s cigarettes hugely comforting. The apron, less so. It is made of a plasticky material that doesn’t feel good when I cuddle her. She says it’s great because it’s wipe-clean, but I don’t like it. I like Granny’s apron, because if you mess, you can scrub and scrub and the stain never quite goes away. Plus, it’s soft and doesn’t stick to my face.

At two I am a precocious, amusing and consistently chubby child. Doughy rather than cherubic. My hair is a short, untameable sticky-outy mass of undefined curls. It is cut regularly by a white hairdresser who has not a clue how to deal with it. Thanks largely to her, I am often, too often, mistaken for a boy. It’s one of my earliest experiences of my identity being called into question or assumed to be something it is not. It never ceases to make me angry; often it proves utterly mortifying. I internalise every incident and feel the need to apologise for myself. What’s more, I have an overwhelming desire to make things okay for whoever hasn’t had the good grace not to ask the question in the first place. In twenty-four short months, I have learnt to feel shame about who I am and become a people pleaser.

I suck my thumb constantly. I will continue to do this until I’m in my late teens, which, as a teenager under the spell of Oprah, I convince myself is related to having been taken away from the breast too early. I also have a blanket, called ‘Blanket’ bought by mummy the night they collected me from the adoption agency. Blanket and I were both new. Even though I’d been handed over by Kris in a yellow one, Blanket was the only one I ever wanted and felt comforted by. Just as Kris had been replaced, so too had the old yellow blanket. In fact, I became so attached to Blanket that when it perished, the only thing for my parents to do was buy an immediate replacement. Sometimes, I would love Blanket so hard his edges would fray and the silky part, the best part, would come away all together and I would have a small, secret piece to carry around with me, because Blanket wasn’t really okay when I was five, six, ten, thirteen, twenty-two. One day the unthinkable happened. I returned home from school to find Blanket on my pillow, recognisable but changed. Too blue, too bright, too arranged. Immediate distress and panic rose up in me as I counted off on my fingers, ‘Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday. WEDNESDAY!’ Maureen, our cleaning lady, came on a Wednesday. Blanket had been sacrificed to that which makes the unclean clean. Every scent, stripped from his fibres, his comforting properties sluiced away. The essence of Blanket was gone and I was enraged. That night I wet the bed.

We live in a small village in Surrey in the South of England where I go to playgroup and, because he is three years older than me, Adam goes to big school. The playgroup is held in the village hall next door to the school, and since both are close to our house, we usually walk there in the mornings. Sometimes if we are late I go in the buggy and Mummy and Adam run behind, with Adam grumbling, ‘We’re going to miss the bell!’ over and over. You get told off if you miss the bell. At playgroup there is no bell and you can just go in when you want to and no one tells you off. Once you’ve said goodbye to your mummy, you go to the cloakroom and must hang your coat on the silver hook with your name written on a white self-adhesive label above it. I love seeing my name, S-a-r-a-h written in big, curly, teacher writing. It confirms who I am, and my right to be there.

The summer I graduate to big school we go to a village fête being held in same the hall where playgroup is held. It’s been only a few weeks since I was last there, but I am a big girl now and I’m feeling nostalgic. I break away from Mummy and Daddy and excitedly make my way to the cloakroom, my see-through jelly shoes sticking to the linoleum with each step. The cloakroom looks different. There are no coats, of course, and no pink and blue lunch boxes cluttering up the floor. But there’s something else. It takes me a few seconds to register but then it clicks. The names have gone. Crudely torn from the wall. Remnants of the labels remain, but not so you can read them. A faded a-r is still visible, but the rest of rest of my name is gone. Ripped away to make way for a new child with a new name. I stand and stare at the spot above my hook for so long that Mum sends Daddy to come and look for me. I am lured back into the main hall with the promise of a beaker of Coca-Cola and a slice of Victoria sponge.

At our house, Mummy does the cooking and Daddy drives off in the morning and comes back home in the dark. I know he is my daddy because he is married to my mummy and he eats a bacon sandwich and drinks a bitter black coffee for breakfast every morning. He also sleeps in a daddy’s bedroom. I think this is normal.

Some of my favourite things are scrambled eggs, riding on Daddy’s shoulders, the waxy feel of his bald head and the smell of his scalp, the smell of maleness. I also love watching cartoons after church on Sunday while Mummy cooks roast dinner, being allowed to answer the telephone (‘Tandridge 4718, hello!’) and Granny reading Peter Rabbit to me. This part of life is simple. I wish everyday meant scrambled eggs and cartoons. Things I don’t like are getting my hair brushed (we all have to sing the ‘Ouch-ouch’ song just to get me through it), driving in Grandpa’s car (which makes me feel sick), Adam hitting me, and Daddy getting home late.

We live in a house that looks normal from the outside – bricks, roof, front door, garden – but which inside is odd, topsy-turvy. It has a downstairs kitchen and a bedroom on the second of three floors, a bedroom that doesn’t quite fit and seems like it must have been a mistake. My family is a bit like our house; looks normal from the outside: a mummy, a daddy, a brother and a sister, but when you look closer you realise it doesn’t quite match. The children don’t look like they fit; they look like they must have been a mistake. My put-together family was assembled by chance, the outcome of a barren womb, a drunken fuck and forbidden love, but to me everything about our family is normal, normal, normal. I can’t explain what love is, but I know what ‘safe’ is and I feel it. Mostly, anyway.

Back at the party and I am sitting in the ‘Pass the parcel’ circle. My absolute favourite party game. I am among the youngest of my little group, so I have already played the game several times before at the birthday celebrations of my toddler clique. Usually it is the ‘big’ boys and girls who win the final prize, but I am plucky and also, since it is my birthday, feel entitled to all the good stuff. The music plays, probably some infantile nursery-rhyme soundtrack stamped onto a vinyl and played on the not-to-be-touched record player. Grandpa is at the controls and every so often, as the parcel is tossed, thrown, and more often, reluctantly delivered on around the circle, he lifts the needle from the record. There is a nanosecond of silence, and then a cacophony of high-pitched squeals. On one of the goes around, the music stops while I am holding the parcel. I frantically rip off a layer of newspaper; it is a tense moment, I want to win, to find out what’s underneath all this wrapping. I am disappointed because I haven’t won the main, proper prize, but because Grandpa is the best, and because he knows how vital it is to keep the energy in pass the parcel, a raspberry-flavoured boiled sweet has fallen out of the paper as a consolation prize. Second best. I can live with that. For now. The music starts again and the magic parcel is once again taken and passed on, taken and passed on. This is my earliest memory. Turning two.