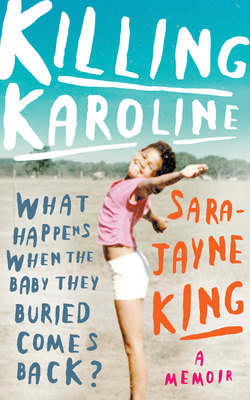

Читать книгу Killing Karoline - Sara-Jayne King - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1 What’s in a name?

ОглавлениеI didn’t become my parents’ child in the traditional way. Neither one of them was in the delivery room when I was born on 1 August 1980 at Sandton Clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Neither had watched me take my first breath or cut the gristly cord attaching my umbilicus to the womb from which I had been expelled. They didn’t even give me my first name. Karoline.

Instead, the people I call Mum and Dad became my parents by way of a couple of signatures scrawled on a piece of paper, rubber-stamping my status as their child. Literally, a rubber stamp, administered by a clerk at Reigate County Court in Surrey, England, on 20 January 1981. That was nearly six months after I had been born and four months since they had collected me from the adoption agency in London, where moments before, a woman – my biological mother – and her husband, the man whose name appeared on my birth certificate, had given me away. At just seven and a half weeks old, they had left me in the arms of strangers and walked away. Because of the colour of my skin.

I was supposed to have been called Emma, after the protagonist in the Jane Austen novel. In the years prior to my ill-fated conception, way before I was born with a large, black question mark over my head and long before I was signed by a magistrate into my adoptive parents lives, that was the name that had been picked out for me by my adoptive father, Malcolm. He had been reading the book while on honeymoon with my adoptive mother, Angela, and had been taken with the name. A smart and opinionated man, he likely had it in mind to raise a similarly intelligent, forthright daughter and was no doubt inspired by Austen’s leading lady, despite her being described by Austen herself as a character she suspected ‘no one would much like’. As it was, the book, which had served as inspiration for the name of the daughter they did not yet have, was left on the beach one day and had been urinated on by a dog. By the time of my birth and adoption some nine years later, my parents had long given up hope of having a daughter and so had bequeathed the name instead to one of their pet goats. So it was that I, when I came to live with them at age seven and a half weeks, came to be known as Sarah. Sarah Jane, perhaps in honour of Austen herself. I disliked the name for years. Incredibly plain, I often thought. Didn’t suit me. It was nowhere near unique enough, glamorous enough, exotic enough, me enough. I felt I should have been a Perdita or a Zara, or at the very least a Jennifer. A name, perhaps, that was hard to spell. But my parents were not frivolous people, so it was unlikely I would ever have been bestowed anything quite as colourful.

On my first day of school I was devastated to discover there were at least three other girls in my class with the same name. By the time I was seven that number grew to about five, and once I had graduated to middle school I was completely insignificant, lost in a sea of Sarahs. So terribly common. The female Johns and Jameses, ordinary, beige and unexceptional. I already knew I was different, so it seemed ridiculous to try to blend into a collective. And so, in what would become my first modification of self, and without consultation, I cast off that which was keeping me in bondage, stuck fast to the unremarkable. Overnight, when I was about 11 years old, I became Sara-Jayne, so that now I stood out on the school register. Standing out was important. Ironically, later in life, I would grapple tirelessly with a desperate need to fit in.

Of course, this initial alteration offered one of my earliest opportunities to learn that making extrinsic modifications to myself in no way altered what it was that I felt on the inside. Unfortunately, I was a slow learner.

As it was, I also hated the name Karoline. It didn’t fit either, but I knew it was – or at least had once been – a part of me, had belonged to me. They had called me Karoline, the biological mother and the man who had believed he was my father. Karoline. With a K. A name that ironically meant ‘joy’. There were already lots of K names in their family and they obviously wanted to continue what they thought was a trend. I sometimes questioned why they’d even bothered to give me a name at all. They had killed me off so early in the tragedy that they would have been forgiven for simply calling me ‘baby’. ‘The part of the unwanted bastard child was played by ‘baby’.’

At various points, during a difficult adolescence when being Sara-Jayne became too much, I considered simply swapping one name for the other. I was still naïve enough to believe that a straightforward substitution would eradicate the feelings of insecurity, discontent and apartheid that plagued me so often. I saw Karoline as my backup plan and felt that I had the right to take the name back. Mercifully, common sense prevailed and Sara-Jayne weathered the storm.

Even before my troublesome teenage years, though, there were signs that I was having difficulty understanding when and where Karoline stopped and Sara-Jayne started. In primary school a friend once asked what my middle name was. ‘Jane,’ I told her, then went on to rattle off the full name I was given at birth, plus the first, middle and maiden names of my biological mother. ‘Ask Sarah what her middle name is!’ my friends would prod each other excitedly, and I would perform my party trick of the thousand monikers. I liked being the centre of my friends’ attention, but at the same time felt uncomfortable that what secured their interest in the first place was something about me that was strange, different, separate, weird, curious and odd. Everyone I knew – except for my older brother, Adam (my parents’ first adopted child) – had the name their mummies and daddies had given them when they were born. Their names hadn’t changed and neither had their parents. Both of mine had and I never really lost the sense that they could again.

Over the years, as my life as Sara-Jayne began to meander along its own path, something happened that I had not counted on. I found myself being drawn back to Karoline. Ultimately, I allowed her to be reborn and then to be laid to rest with a dignity she had not been afforded by them. What I can say is that after all that has happened, Karoline has now gone, which is strange because in one sense Karoline is me, in another I am Karoline, and my story is about both of us. What happened to her and why, and what happened to me and how?