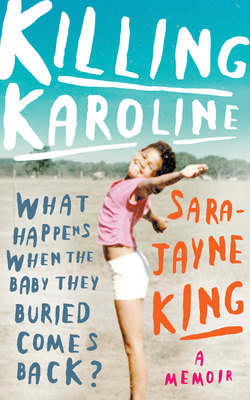

Читать книгу Killing Karoline - Sara-Jayne King - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2 An immoral act

ОглавлениеEven before I was born, I was a problem child. A problem unborn child, but a problem nevertheless. When I made my entrance into the world by way of the surgeon’s knife, eight days earlier than expected at the Sandton Clinic in Johannesburg on 1 August 1980, one of history’s most abhorrent political ideologies was firmly in place in South Africa. It was also one that would ensure the first few weeks of my life would be nothing less than ‘problematic’.

Although it existed for years as a social movement, apartheid was officially introduced into law in South Africa by DF Malan’s Herenigde Nasionale Party – the ‘Reunited National Party’ – on his party’s victory in the 1948 whites-only general election. From that moment until its theoretical end in 1994, the government introduced legislation to reinforce its desire to create a racially divided South Africa.

In 1950, two key pieces of legislation – the Population Registration Act and the Group Areas Act – were passed, requiring strict classification of all South Africans according to racial group. This classification would determine where people, people who weren’t white, could live and work. And who they could get in to bed with. People were classified as either White, Indian, Coloured or Black (‘Native’), often on the basis of spurious criteria. In South Africa the term ‘coloured’ is used to describe someone with mixed ancestry, with origins in southern Africa and other parts of the world, including India, Malaysia, Indonesia and Europe. They are the descendants of slaves and slave owners, the colonisers and the colonised.

Such was the significance of racial classifications under apartheid that a designated office was set up to monitor the classification process. Where a person’s race wasn’t immediately obvious, or if someone wished to be reclassified (usually from coloured to white), certain tests were carried out to determine which group people should be assigned to. These tests were based on public perception of the individual and by their appearance: skin colour, facial features and, infamously, hair. The now notorious ‘pencil test’ decreed that if an individual could hold a pencil in their hair when they shook their head, they could not be classified as white. Such was the absurdity of these tests that often members of the same family would be separated into different racial groups, resulting in divided families, forced apart by the government’s nonsensical policies.

Later, the National Party government enacted further laws that would segregate and control all areas of life, from political rights, voting, freedom of movement, property ownership, leisure, education, medical care, transport, social security, taxation and, of course, sex.

The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act (prohibiting marriages between ‘Europeans’ and ‘non-Europeans’) was among the first pieces of apartheid legislation to be passed following the National Party’s rise to power and, together with the pre-existing Immorality Act, sought to further enforce the idea of a ‘separate’ South Africa. The word apartheid literally translates from Afrikaans as ‘the state of being apart’, or ‘apart-ness’.

Apartheid proper had been established in law for just over three decades by the time my biological parents committed their illegal, ‘immoral’ sin and I, as the result of their misdeed, had been born a crime of the very worst kind. An indiscretion of Shakespearean proportions – ‘Now very now a black ram. Is tupping your white ewe.’ Theirs was a union that not only terrified proponents of apartheid, but one that was enshrined in the statute books as a transgression so dark and foul that it carried with it, in law, a penalty of incarceration, but in actuality, a punishment often far worse.

While over time I came to understand what had happened to Karoline, learning in very basic terms what apartheid was and how my conception was deemed a criminal act, it wasn’t until I saw in black and white how vehemently the apartheid government sought to prevent the types of union from which I was born that I understood the significance and gravity of what I represented.

IMMORALITY ACT, NO. 5 OF 1927

To prohibit illicit carnal intercourse between Europeans and natives and other acts in relation thereto.

BE IT ENACTED by the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, the Senate and the House of Assembly of the Union of South Africa, as follows:–

1 Any European male who has illicit carnal intercourse with a native female, and any native male who has illicit carnal intercourse with a European female … shall be guilty of an offence and liable on conviction to imprisonment for a period not exceeding five years.

2 Any native female who permits any European male to have illicit carnal intercourse with her and any European female who permits any native male to have illicit carnal intercourse with her shall be guilty of an offence and liable on conviction to imprisonment for a period not exceeding four years…

Ironically, almost twenty years to the day since the National Party’s 1950 amendment to the 1927 Immorality Act (extending the ban on sex between whites and blacks to include all non-whites), a sex scandal involving several enthusiastic supporters of the National Party would strike at the very core of the colour bar when it hit the small Free State town of Excelsior. Seven local Afrikaner farmers and businessmen and fourteen black women were arrested and charged under the Act, after a number of mixed-race children were born in the neighbouring township of Mahlatswetsa. Such was the stigma attached to interracial sex that the backwater town became world renowned, with the Chicago Tribune featuring the story in its 2 December issue of 1970.

‘If an atom bomb had been dropped on our town, it could not have had a greater impact,’ one elderly farmer says. Asked to describe Excelsior and its 700 white residents, he said: –

‘Well, let me put it this way. This is an Afrikaner’s town. There are no foreigners here. We had two Greeks, but they left.’ The law has shattered many lives outside Excelsior in recent years. A Cape Town judge jailed a 38-year-old white father of four for four months for conspiring to commit immorality with his mulatto maid … Sometimes judgments seem odd. Two white men were acquitted but two black women charged with them were tried separately and convicted.

Almost precisely ten years after the Excelsior outrage, my biological parents would create their own scandal. Doing one of the most natural things one human being can do with another, they too played out the very thing the architects and supporters of apartheid feared the most. A mixing of the races. A merging of black and white. Such a union, and more so the issue of such a union, served only to undermine in the strongest possible way the entire system on which apartheid was based. In their own way, the white British ewe and the black South African ram challenged the very essence of institutionalised racism that former South African prime minister, and the so-called mastermind of apartheid, Hendrik Verwoerd, sought to create: the maintenance of white domination and the separation of the races. The Immorality Act was eventually repealed in 1985, five years after my birth, but not before thousands of people had been convicted for having sex across the colour line.

By the time my biological parents had begun to make the beast with two backs, Nelson Mandela was already languishing in prison on Robben Island, sixteen years into a life sentence for committing sabotage against the apartheid government. PW Botha was heading up the National Party and racial tensions were just a few years away from becoming the worst the country had ever seen. But in a well-to-do enclave in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg, my biological mother was doing her bit to improve race relations.

Born in the North of England in 1957, my biological mother, Kris, found herself in South Africa because of a man. She had met Ken while they were both studying at the same college in the South of England in the late seventies. She had transferred from a college in the North to one in the county of Berkshire where Ken was also a student. His parents had emigrated to South Africa when he was three, but when he was seventeen he had decided to go back to the UK to complete his education.

Five years afters arriving back in England, and having finished his studies, Ken decided to return to South Africa to work for his parents. They had built a successful career for themselves in the catering industry and his father had achieved an influential position in a chain of hotels. And so, at the age of twenty-one, having been dating Ken for two years, Kris agreed to go back with him and they both began working in the affluent area of Sandton in Johannesburg, him managing his father’s restaurant, she as head housekeeper at the popular Balalaika Hotel.

The Sandton of the time was not the Sandton of today, which now boasts the title of ‘Africa’s richest square mile’. There were very few office blocks, the roads were suburban and there were no multiple lanes of traffic clamouring and careering through the city. At the time it was still little more than a residential suburb and Sandton City, considered today to be the ‘Rodeo Drive’ of Africa, sprawling with exclusive stores and upmarket eateries, was just a small shopping mall. The Balalaika was just around the corner in Sandown and was a well-known and well-liked ‘country’ hotel, popular with locals.

It was at the Balalaika that Kris met my biological father, Jackson ‘Jackie’ Tau (Tau means ‘lion’ in Sesotho) who, she would once describe in a letter to me as ‘different’ and ‘a cut above the others’, but unable to reach his full potential because of the politics of the time. He was thirty years old and head chef of the hotel restaurant. Jackson was married, with a wife who lived in the ‘homelands’, most likely QwaQwa (which translates as ‘whiter than white’), the region created by the apartheid government for Basotho people, as I’m told my father was. The homelands, or Bantustans, formed the cornerstone of apartheid policy and the white minority government’s desire to divide and rule. Residential areas were segregated by means of forced removals. The black majority was stripped of their citizenship and, depending on their ethnic group, assigned to the relevant, tribally based ‘self-governing’ homelands. But, being a largely mountainous area and less than suitable for cultivation, most of the men of QwaQwa left to become part of the migrant labour force, providing cheap labour for white-owned businesses.

At the time I was born Jackson already had one child, a daughter. He later had a son.

I have just one picture of my biological father, sent to me by Kris, more than twenty years after it was taken. It was the only one she had, she wrote, and she had kept it in an album from that time. In the picture, his head is turned to the side, allowing only for a side profile.

My father is half a face. An ear to match my own, the tight kink of my Leo’s mane, the too-wide African nose that belongs to his face, but that is unwelcome on mine. An eye, a forehead, my lips, a chin. We have identical hands. My father reminds me of myself, but only the good parts. If all the black and swill and spit and mire had come from her, then the light, the glow and the music must have come from him. In my mind his voice sounds like sugar beet, soaked overnight, heavy and thick. It is an adagio. Although, to the best of my knowledge, my father never met me, if I close my eyes I can hear him singing and see him cradling me on his forearm while he smokes a cigarette.

Thula thul, thula baba, thula sana, Thul’ubab uzobuya, ekuseni. Thula thul, thula baba, thula sana, Thul’ubab uzobuya, ekuseni.

(Hush, hush, hush-a-bye little man, Be quiet, baby, Be quiet, Daddy will be back in the morning. Hush, hush, hush-a-bye little man, Be quiet, baby, Be quiet, Daddy will be back in the morning.)

I like to imagine that when he walked into a room, he did so with his eyes up, his feet unapologetic, his chest proud. When they called him ‘kaffir’ he would smile. When they smiled and called him Jackson, he would raise a correcting finger and say ‘Mr Tau’, and when they called him ‘kaffir’ again, he would, in turn, smile again. I pretend I know my father. I pretend to know that his greatest desire in life was to be a good man. That his indiscretion with my biological mother didn’t mean he loved his wife any less. Rather, he saw someone breaking, ready to shatter, and felt compelled to protect her. In my mind my father is Othello.

Despite it being virtually unheard of for black and white people to be friends, my biological father and Kris, in her words, ‘got to know’ each other and started jogging together in the early morning before work.

In one of the three letters I ever received from Kris she once said of their relationship:

Absolutely no one guessed that what appeared to be just a couple of hotel staff becoming friends was in fact a deep and understanding relationship. And while the relationship grew, Ken and myself grew more and more distant.

The relationship continued, the threat of imprisonment apparently not enough to prevent them embarking on their perilous tryst and eventually, in the December of 1979, my biological mother became pregnant with me. Choosing not to disclose her affair, Kris told Ken of the pregnancy and they married shortly after, exactly five months before I was born. None the wiser as to her secret, both Kris and Ken’s white families looked forward to their first grandchild.

Ken, believing the child his new wife was carrying was his, was apparently ‘overjoyed’ at the prospect of becoming a father, but Kris carried the nagging, shameful doubt that the baby growing inside her was the result of her affair with Jackson.

My relationship with Jackson came to an end when it was discovered I was pregnant, but he saw no reason that it should, and he did not want to believe that there was even the remotest possibility that I was carrying his child.

For the duration of her pregnancy she hid her terrible secret, confiding only in her doctor, who of course was unable to prove my paternity until after I was born. My future rested entirely on my race. As it was, when I was eventually pulled from her on the winter’s evening of 1 August 1980, it was apparently not immediately clear that I was Jackson’s child and I was pronounced a ‘white’ baby, given the name Karoline, and believed to be the first child of an unknowingly cuckolded, but apparently delighted Ken. To this day, it is his name that appears on my birth certificate.

Over the years I often tried to imagine the conversation that must have taken place between Kris and Ken when thinking of a name for me. These regressive fantasies were one of the perverse ways I’d torment myself when the aching, unyielding agony of the unknown became too much to endure.

I imagine the pair of them, like poorly rehearsed movie stars, awkwardly acting out the scene in a plush bedroom filled with congratulatory cards, grand furniture and thick shag-pile carpets. They are young and rich and good-looking, but their Hollywood life is days away from crashing into a low-budget made-for-TV movie. It is 3 August 1980, three days since I entered the world (eight days earlier than expected), cut from the mother’s womb by the doctor’s knife. Mother and baby have been allowed to return home. Ken walks out of the bathroom into the bedroom, oblivious to the wet shadows his feet are leaving on the carpet. A white towel is around his waist, his upper body still red and damp from the shower. She stares at the freckles on his shoulder and imagines how it would feel to suffocate one’s own baby.

He stands over the two of them, mother and newborn; he’s carrying a large portable phone, grinning, with his toothbrush wedged into the side of his mouth.

‘That was the old man,’ he nods his head in the direction of the phone. ‘Says to tell you well done, good job, next one will be a boy.’

He bends down and peers at the baby, milk-drunk on the mother’s breast. Kris inhales sharply. ‘Next one?’ she says incredulously, shaking her head despairingly. He pretends not to notice. ‘Katy, Kitty, Kadance …’ he muses, letting the towel drop to the floor.

The radio hums in the background, playing the number-one hit by local female vocal group, Joy. The song is an anthem for South Africa’s struggle movement and the lyrics speak to the burgeoning sense of unrest in the country. The women sing of burning bridges, blazing skies and a woman weeping while a man lays beaten, but also of the promise of better days, which are to be found down the elusive ‘Paradise Road’.

‘I like Joy,’ she breathes into the room. Steam has begun creeping under the bathroom door.

He turns to face her, his cock erect and aggressive. She baulks. ‘Karoline!’ he announces, winking at the sleeping baby. ‘Ken, Kris and Karoline! With a K.’

[Fade to black.]

Of course none of this really happened. I was given the name Karoline, Karoline Mary, because both Kris and Ken liked the name and wanted to keep up the tradition of Ks in their respective families. Mary was in honour of Ken’s great-grandmother who turned ninety-nine the day I was born.

Kris and I eventually left hospital on 9 August. In those days, a new mother stayed in hospital a lot longer than she would today, but even after nine days, I have been told, there was no sign that I was not the child Kris had hoped I would be. The story goes that it wasn’t until I was three weeks old that she began to see signs that Jackson, and not Ken, was my father. It seems unbelievable, from her side at least, given what she knew, that she would not have realised sooner, instantly even, but so it was that nearly a month went by before my true paternity came to reveal itself.

A referral letter from a paediatrician at Sandton Clinic to child welfare authorities in the UK states:

This is to certify that I saw this child at it’s [sic] Caesar on 1.8.80. Mother’s first pregnancy which was normal … The main problem here was the paternity of this child as we were concerned initially whether this was in fact a Caucasian or non-Caucasian baby. Most of the features were those of a Caucasian baby, the things against it were a slightly flattened nose, a rather darkened vulva and darkened areolas.

Kris considered leaving both South Africa and Ken, and returning to England to decide what to do, but in the end, after a night of candour, reprisals, questions and answers, she confessed her sins to her husband. The husband who had soothed, bathed, played with, loved as his own the child fathered by another man, a black man, employed at his own father’s hotel, just a few short months before his wedding.

Where many men in Ken’s situation may have left the marriage, he decided to stay. Years later I would ask him why. ‘I loved her,’ he had told me. ‘But also I wanted to save face.’ Kris, he said, had not been very well liked by his family and perhaps he felt he had a point to prove.

And so, because Ken stuck around, so did the problem, the problem child, and desperate times required a solution to be found to rectify the problem.