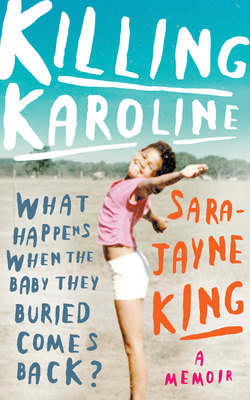

Читать книгу Killing Karoline - Sara-Jayne King - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 4 Sarah Jane is adopted

ОглавлениеMy adoptive parents were never really meant to have been my mother and father. It’s an unpopular opinion, usually among APs (adoptive parents) and well-meaning social workers who want the adoption machine to keep turning and churning out rainbow families. They forget that at the start and the heart of every adoption story is pain. I wasn’t orphaned, I had two parents (three if you counted Ken), but I was just unwanted. As I say, it’s an unpopular opinion among non-adoptees, many of whom would rather hold on to the idealistic view that adopted children are somehow born for the sole purpose of becoming part of their adoptive families. Some even go further, suggesting that the universe or, more difficult for me still, ‘God’ has pre-ordained the adopted child’s place in their ‘new’ family. But, for me and many other adoptees I have come to know over the years, this is really just an attempt at sugaring a very large, very bitter, very white pill. Because, in its basest form, adoption is a social construct, designed to kill three unfortunate birds with one stone. It is not what nature intended; in fact, it goes completely against the natural order of things.

I came to be my adoptive parents’ child not because of some altruistic motivation on their part to step in and rescue an unwanted child, but because, devastatingly for them, they were unable to have their own children. If I were a believer in such things I might conclude that their infertility was a sign that perhaps theirs was a life in which children were not destined to be a part. My take on this is not a popular consensus.

In 1971, my mum Angela, a liberal conservative from a privileged and proper, upper-middle-class family in the heart of England’s home counties, marries my father Malcolm. She is thirty-one. Old for the time. Her parents, my grandparents, both come from well-off backgrounds, and my maternal grandmother’s family was certainly considered very wealthy. My great-grandfather works ‘in the City’ and amasses something of a fortune, affording him such luxuries as a Rolls Royce, a personal driver and live-in housekeeper, and even a family trip to New York, which my grandmother records in her diary at the time: ‘We visited a nightspot on the island of Manhattan this evening and watched the negroes jive dancing to a very up-tempo jazz band.’

My mother and her younger brother, Jonathan, both attend private schools, travel abroad when it is uncommon to do so and receive considerable financial assistance from my grandparents for cars, weddings and, later, property.

I am close to my maternal grandparents, Granny and Grandpa. More so my grandmother, who is as grandmothers are in storybooks: white, plump, grey-haired and ample-bosomed. Granny – or Madge, as she is known to her friends, Madeline officially – teaches me how to make rock cakes, and is excellent at tucking me in at night, pulling the duvet and blankets right up around my chin and then folding it in at the sides so that I’m cocooned in cotton.

She is proper to the extreme and refers to the loo as the ‘lavatory’ (never the ‘toilet’), and is well into her eighties (and me my late teens) the first time I see her out of a skirt and wearing a pair of trousers. When she answers the door in her new ‘pants’, I start for a second, unable to recognise her.

When my playing is good enough, Granny and I play duets on the piano, and when I stay the night with her and Grandpa we read aloud from Peter Rabbit and Swallows and Amazons. Despite her propriety, Granny is a hoot, and very frank. When I am nine we howl with laughter at the rude bits in A Fish Called Wanda and when, as a curious twelve-year-old, I ask her, ‘How many times do you think you and Grandpa had sex?’, she tilts her head, considers and says simply, ‘Thousands, darling.’

One day, when I am eight, we watch the summer Olympics taking place in Seoul. As their generation commands, Granny and Grandpa are patriotic, so we have been glued to the athletics for over an hour. The presenter announces the next event, in which a man named Peter Elliott is running the 1500 metres for Great Britain. As Elliott and the rest of the competitors (including a black runner from Kenya) crouch at the starting line, Granny turns to me and says, ‘I’ll cheer for Britain, you cheer for Africa.’ For a reason I do not understand at the time, I am hit by a feeling of loss and also panic. It’s the same feeling I get when I lose sight of Mummy in the supermarket. For the next three minutes I watch the thin, black man hurtle around the track, my fingers crossed in my lap willing him to lose. He pips Elliott by less than a second, and at the same time manages, by a toe, to create a further irreversible separation between me and the family I think are mine.

There is never a doubt in my mind that Granny loves us. Me especially; Adam is more difficult because he is often naughty, but because I am mostly good and smart and easy (I exhaust myself to achieve this), I am definitely loved. I think my cousins, my uncle’s two daughters, several years older than us, are loved more, but understandably. They are proper grandchildren and look like Grandpa. Adam and I are denied full, peak membership to our family because we don’t have the ‘family nose’.

Grandpa John is even better than a storybook Grandpa because rather than smoking a traditional pipe, he is always sucking on a special machine that makes a chugga-chugga whirring noise. He has to do it for his lungs. When he breathes in through the mouthpiece, his whole chest heaves, and the braces that he always wears attached to his trousers look as if they will ping right off his body. Because of his bad lungs he didn’t have to go to the war and could stay away from the battlefield, instead growing vegetables in his nursery. Grandpa teaches us and our friends how to gamble using coloured counters, and we are masters at Black Jack before we are in middle school. He loves us too, but in a less tactile way than Granny. I remember hugging him only once in my life, before bed one night, and it felt strange – for both of us, I think – and I never did it again.

One of my lasting memories of Grandpa is of him in hospital a few months before he died. The hospital was close to my school and I had been told to walk there and meet my mum instead of catching the school bus home.

When I walk into his private ward, weighed down by my school satchel, Grandpa is having his blood pressure taken. A nurse I’ve never seen before turns to look at me, as I plop down into the plastic orange NHS chair by the bed. ‘This is my adopted granddaughter,’ Grandpa tells the nurse. He says it very matter-of-factly. The nurse keeps staring and then half laughs, awkwardly. I feel alien and confused sitting on that too-high chair, because even though I am adopted, I have never considered myself to be the ‘adopted granddaughter’. I don’t think of John and Madge as my ‘adopted grandparents’; they’re just Granny and Grandpa. But suddenly I am ‘other’. Other than what I’ve believed myself to be. Different. Separate. Not ‘real’. Real granddaughters, like my uncle’s children, are obviously better. They don’t need explaining.

I find it further destabilising when people ask if Adam is my real brother. I know what they’re asking, but it feels like they’re implying he may not be genuine. That he’s an imposter. That a real brother is out there somewhere and Adam’s just filling in. To me he’s as real as can be. When he punches me, it hurts and when he wins a race on sports day, I cheer the loudest.

People talk about my adopted mum and dad, or worse, refer to them as my foster parents. When they do, it’s like they’re saying my role as ‘daughter’ is temporary, uncertain, non-permanent. I know all about foster parents. They let you go. They have no obligations. I know this because Mum is a social worker and sometimes has to take unwanted children to their new foster homes in our car. One little boy, Connor (who is black like us) I meet a few times over the years as he moves from family to family, each time carrying his belongings in a black bin liner. I often wonder what is wrong with Connor. Why does no one want him? What is it that he does wrong at all these foster homes? One thing I know is that I’m certainly not a bin-bag child. I have a chest of drawers for my clothes and my own hand-me-down travel case with a tarnished bronze lock that doesn’t close properly.

Of all the things that grate me, the worst is when Kris is referred to as my ‘real’ or ‘natural’ mother. I am always puzzled how a woman who relinquishes her child in the manner in which mine did can be bestowed such a title. The various terms used by the well meaning and the ignorant disturb me greatly and, as a child, it is troubling to learn that there are such things as ‘real’ and ‘unreal’ family members. For a long time, though, I steel myself and fall in line with the language other people feel comfortable with or feel entitled to use when discussing my curious family. My voice is still too quiet to be heard over the din of other people’s needs.

My father, Malcolm, a few months younger than my mum, was born in Sheffield, Yorkshire, in 1940, the son of Arthur Kirk, a coal miner, and Maggie (Margaret) – or Yorkshire Granny, as we called her – a housekeeper. They met when Maggie went to work for Arthur. A widow with an infant child (my father’s half-brother Albert), Maggie went onto marry Arthur and, in doing so, inherited thirteen stepchildren, several of whom were older than she was. When she was forty and Arthur sixty, my father was born. I never once heard my dad speak about his father. I have no memories of my paternal grandmother and only one of ever going to Sheffield, where my father had grown up. It was for Albert’s funeral, and I was about eight or nine. The three-and-a-half hour journey up the M1 was interminable, and the stench of home-made egg sandwiches (my parents were frugal enough not to believe in over-priced road-side café fare) made my car sickness worse than usual. We stayed with an old friend of my father who had a tiny house in a tiny village on the outskirts of the town. We all had to share a bedroom and, despite being covered in a thick, rough blanket and being crammed into a small put-you-up bed between my mum and my brother, I shivered through the night.

The funeral – the first I’d ever been to – was well attended and we got to ride in a special long black car, with seats that faced the front and the back. We were crammed in with my uncle Albert’s widow and son (my never-mentioned cousin) who talked incessantly. Their accents were so broad that I didn’t understand a word, and I remember praying they wouldn’t speak to me, lest I had to keep saying ‘Pardon? Pardon?’ There was a wake following the burial, held at another tiny house in another tiny village. It smelt like chips and egg. The people, too, smelt like chips and egg and they were utterly miserable. I got a sense that their misery wasn’t confined purely to the nature of the occasion. My lasting memory of the whole experience was that in Yorkshire you were always crammed in, people called you ‘duck’ and it smelt like chips and egg. It was grim up North.

Unwilling to follow in his father’s footsteps down the mines, when he was old enough Dad travelled to the South of England where his prospects were considerably brighter. He was determined to escape the bleak reality of mining life as the only future for a young man in Sheffield at the time. Of above average intelligence and having excelled at school, at the age of seventeen he secured an apprenticeship with an international electronics firm and moved to London. By the time he came to be my dad, nearly fifteen years later, the only clue that he wasn’t from the South was when he would lie on the landing outside my and Adam’s shared bedroom and sing, in his round, quite tuneful tenor, the anthem of the Yorkshireman ‘On Ilkley Moor Ba’Tat’. His own broad Yorkshire accent had also, by then, all but disappeared, after years living among plum-mouthed Southerners, save for those occasions when he became angry and his vowels sharpened instantly as if he’d never left t’moors. It was partly because of my father’s Northern roots that Kris chose him and Mum to be my parents. She too was from ‘up North’ and felt some sort of affinity with Dad as a Yorkshireman.

Despite their vastly different backgrounds and just six months after meeting at a coffee evening hosted by mutual friends, Angela and Malcolm marry at a registry office. Both are equally keen to start a family and agree they want four children. But two years into their marriage and now thirty-three, my mother still hasn’t fallen pregnant. After years seeing five different GPs for a referral to a specialist clinic, they eventually follow a friend’s recommendation to see a consultant at Chelsea Women’s Hospital in South-West London. My mother once told me about that first appointment:

The consultant was an elderly man in a dark suit and with a carnation in his buttonhole – very much the old school. He was optimistic that with hormone injections I would get pregnant. These were very painful and I used to hobble round to Harrod’s for a snack afterwards to cheer myself up. There were also lots of other tests I had done, but the doctors still couldn’t make out why I wasn’t getting pregnant; although I seemed to once, but then they said I wasn’t. Dad’s sperm test was fine. I also had had a miscarriage on another occasion. I stuck this out for three years and then this lovely old consultant suggested we consider adoption.

Mum is always wistful and sad when she talks about her not being able to have children. Understandably so, but I’ve always felt that her sadness was greater than her desire to reassure us, Adam and I, that we were enough. Not just enough, but that our becoming her kids was actually sufficient to eradicate, or at least usurp her own disappointment at not being able to have her own biological children. For a long time, I silently resented her for that. When I was young I would fret about what would happen if by some medical turnaround my mum fell pregnant. What would happen to us? Would we be sent back? Or passed on to yet another family who needed a child to make them feel complete?

The problem was that, although I know I was loved by my parents, there was always the feeling that I was the consolation prize. I was not their first choice. If they had been able to have children, Adam and I would have simply been taken in by some other barren couple who needed to fill an emotional void. We would never have been Adam and Sarah Jane. That troubled me.

Never once in thirty-something years have I ever heard an adoptive parent speak about their desire to adopt being based first and foremost on a need to provide an unwanted child with a family. I’m not suggesting they’re not out there; I’m saying I’ve never met them. The driving force always seems to be to meet a need for that parent. To allow them to fill the child-shaped hole in their lives. For a long time I felt guilt and enormous hurt at not being the child my mother really wanted. It wasn’t even that I wasn’t a true part of her, that she hadn’t carried or breastfed me, or that if things had worked out the way she wanted, I would never have been her daughter. It was that I sensed she felt that had she had a biological daughter, the child would have been more like her, an extension of her. Someone for her to mirror and be mirrored.

As I grew older, particularly in my teens, I would be overwhelmed by the sense that my mother was eternally disappointed by me. I wasn’t the daughter she had really wanted – not as a baby, and certainly not as an angry, confused teenager and young woman fraught with problems. That of course gave me further reason to resent her, I felt so desperately misunderstood and unable to speak about the feelings of sadness, insecurity, abandonment and otherness that haunted me every day. It is a familiar feeling among adoptees. That we must be silent and, above all, constantly grateful.

In their bid to become parents, Mum and Dad wrote to nearly a dozen adoption agencies. It was the early seventies and, socially, things were beginning to change. There was no longer such a stigma against unmarried mothers, and the contraceptive pill was readily available. This meant there were considerably fewer babies available for adoption. Eight organisations wrote back saying that their waiting lists were closed, but the Independent Adoption Agency wrote back asking them to fill in a questionnaire.

The questions included whether they would consider adopting a child with learning difficulties. Dad thought he couldn’t cope with this and Mum thought she couldn’t cope with a child with ongoing physical needs. But they both agreed, believing it to be a good thing, that the colour of a child’s skin made no difference to them.

Eventually, in 1979, they were approved to adopt. They were initially introduced to George. George’s story is every adopted child’s worst nightmare. As a small boy, he had been adopted by a British couple living in Hong Kong. When, a few years later, the couple had a child of their own, they decided they no longer wanted George and apparently tried to convince him that he didn’t want to live with them. They succeeded and George was bought to England to be put up for adoption again. After a weekend with George, Mum and Dad decided he was not the child for them. I often wonder about George and pray he cannot remember any of this.

A few months later they were told about another boy, a toddler of eighteen months living in a children’s home on the small Channel Island of Jersey, having been given up by his biological mother, a woman named Margaret. Margaret was a chronic alcoholic with a history of mental health issues, who claimed to have had a fleeting relationship with a Jamaican man, resulting in her becoming pregnant. (Years later we discovered that she had fabricated the story and had no recollection of the father, least of all his country of origin.) She gave her son the name Aaron. She was a big Elvis Presley fan and named him after the The King, Aaron being the singer’s middle name. My parents flew to Jersey to meet and bring Aaron back to their home in Surrey where he would be their son and, later, my brother. They changed his first name to Adam, they say to avoid bullying, but I wonder if, in part, it was also to make him more ‘theirs’.

At eighteen months, Adam spent the entire flight back to London trying to drink from the gin and tonic my mother had ordered from the air steward. No one realised then that the incident was a precursor to what would follow in the years to come.

After Adam had been living with my parents for a while, they decided it would be nice if he had a sibling. A sister. It was suggested to them by the social workers that their second child be ‘similar’ to their first. Less contrast, similar ‘challenges’. I asked my mother once what ‘challenges’ they were referring to; ‘Raising non-white children in a white community,’ she said. Strangely, though, none of these ‘challenges’ would ever be discussed in our family. They simply brewed under the surface of the smooth, yet unhelpful veneer of colour-blindness, naïvety, denial and, ultimately, I think, in my parents’ defence, love.

I once asked my mum if she would ever have married a black man. She replied with an answer that troubled me. She said that she didn’t think she would because they would have nothing in common. I realised then that Mum did not, perhaps could not see who I was outside of being her daughter. Where the colour of my skin had been the very reason I had been given away by Kris, to Mum it was no more than an aesthetic difference between us. And so while we knew we were loved, my parents’ ignorance and inability to acknowledge our skin colour as being crucial to our identities ultimately led to both Adam and I navigating, in isolation and confusion, a painful and self-destructive path to make sense of who we were as individuals and in the world at large.

By the time my parents adopt me, they are both forty, although my mother, having been born in March, has eight months on my father. I think this is strange; daddies should be older than mummies. That’s just the way it is. Like Tom always chases Jerry and teachers don’t have first names. They’re always Mrs So-and-So, or sometimes Miss So-and-So, but never Sally or Anne or Lucy. Either way, forty is old. Much older than my friends’ mummies, who are all in their mid- to late twenties, maybe early thirties. When I am old enough to be concerned by such things I am embarrassed by Mum’s ‘old-fashioned’ clothes (particularly her disregard of ‘pointy’ heels), her refusal to let us eat McDonald’s (I have my first Big Mac aged twelve at a friend’s birthday outing), or even have sugar in our tea. She is so old fashioned. Only Jessica Hartley-Moore’s mummy is older than mine, and that doesn’t really count because she’s got a much older sister who’s already a grown-up and Jessica was an accident anyway, whatever that means. As a child, I often think to myself that Mummy should have adopted me when she was younger. It would be nice to have a younger mummy, I think. It doesn’t occur to me that I wouldn’t even have been born a few years before! As far as I am concerned, there is no kismet between the time Kris decides to give me up and the time my parents are ready to adopt another child. It’s as if I believe they were somehow given a choice as to when I arrived, as is the case with ‘normal’ babies.

Not only were Mum and Dad not given a choice as to when I arrived, they certainly weren’t given much notice either. They were asked if they’d like to be considered to adopt a baby girl coming from South Africa only two weeks before I came to live with them and were only told Kris had chosen them from a list of potential parents some 48 hours before they collected me. My mother has described those two days as a frantic rush to acquire all the necessary paraphernalia required for an eight-week-old baby. How she rushed off to buy bottles, baby formula, nappies and baby clothes, having been told I would be arriving with nothing. She loves to tell the story of how none of the clothes she bought me fit, despite them being for a baby zero to three months old. She had to return them and exchange them because I was fat, like a ‘little Michelin Man,’ Mum says.

I am eight and a half weeks old when they collect me from the adoption agency in Camberwell in South London on 30 September. It is a Tuesday. I am handed over by Kris with just three babygros, a tube of baby cream (my mum still has the pink Johnson & Johnson tube with the swirly blue writing) and a yellow blanket. I often wonder whether those were all the clothes I ever had (perhaps because she knew she wasn’t keeping me, she only bought the bare minimum?) or whether she kept some.

I bond well with my new parents, am a ‘good’ baby, and Angela and Malcolm are delighted by the new addition to their family, although Mum loves to tell the story of how Dad went into blind panic when, a few days after my arrival, he is literally left holding the baby as my mother announces she is heading to her upholstery class.

Mum loves to upholster. Most of the things she upholsters are things no one wants any more, cast off by their owners; they are things she has found in junk yards, and at antique fairs and the like. Mum does her best to make them like new again. Not new actually, because she doesn’t make them look exactly like they where when they were new, but rather more to suit her taste. One of the pieces she has worked on at evening class is a Regency-style armchair, which when she found it had been discarded in a hedge covered in ugly black leather. On the seat part, some of the leather has been torn in places and you can see the white foam padding trying to escape. After a few weeks, Mum stuffs the padding back inside and sews a nice new flowery fabric over the tears. The chair is then good enough to be put around the dining table and for years everyone declares what a wonderful job she’s done fixing something most people would have just left to rot in the undergrowth.

According to my mother, I showed absolutely no sign of distress at being parted from Kris. But while that may have seemed to be the case when I was a baby, years later the distress would rise to the surface in the form of an uncontrollable fear of abandonment, crippling self-doubt, relationship problems and pityingly low self-worth. And these feelings would, in turn, come to manifest in a number of self-destructive behaviours.

People often ask me when I found out I was adopted. They want to know how my parents told me. The question always makes me feel like a curiosity. I know what they’re hoping for – something worthy of a soap opera, a story involving some theatrical revelation, but I don’t have one. To my parents’ credit, I don’t ever remember being told. I just feel as though I’ve always known. The same way I know that fire is hot and that one’s brain is in one’s head and not one’s feet. Interestingly, I often wonder whether they hadn’t told me at such a young age, when I would have worked out for myself that I couldn’t logically be my parents’ biological child. When I was little, ‘adopted’ was never a dirty word in our house. It wasn’t an anything word. It was just a word. We didn’t celebrate it, we didn’t revere it, we didn’t have a special adoption song or a sanctimonious spiel that we trotted out every time it was mentioned. Adopted just meant that because Mummy couldn’t grow a baby, that I didn’t grow in her tummy, I grew in another lady’s tummy and when I was a baby she gave me to Mummy and Daddy. It really was very simple. Plus, I had a book that told me all about it which I read over and over. I could read by the age of three, thanks largely to Big Bird, Cookie Monster, Grover and the other residents of Sesame Street.

On Sesame Street, there are a couple of kids whose skin is brown like mine. They talk to a scary creature who lives in a dustbin. I close my eyes when he comes on the TV. It is, in part, thanks to Jim Henson and his strange band of Muppet friends that I love to read and one of my favourite books is Jane is Adopted. Because I know I am adopted and because Jane is my middle name, I think it has been written for me. In the book, Jane’s skin is not the same colour as mine and the mummy doesn’t look quite right, but I am prepared to overlook this.

The pictures in Jane is Adopted show me how it works. A lady with red hair and a smiley face has a big tummy. Then on the next page she is holding a baby. Then she gives the baby to a lady in a green dress and a man with a moustache like Daddy’s. They are smiling too. At the end, there is a little girl sitting on the lap of the lady with the green dress; she is smiling too. Adoption just means lots of smiles and everyone is happy. When I am much, much older, I will write to the author of Jane is Adopted and tell her how much her book meant to me as a child. She will sign a copy and send it back to me, but by then I will know the truth about adoption.