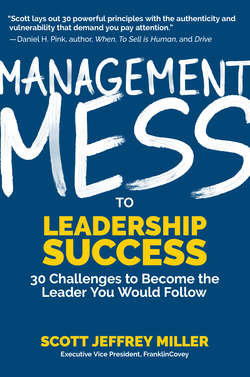

Читать книгу Management Mess to Leadership Success - Scott Jeffrey Miller - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIt was a dramatic start to my leadership career. After four years working as an independent salesperson, I accepted a promotion to lead a group of ten peers. Most of them had been at the job longer than me, had invested in and developed their own sales skills, and in several ways were more proficient than I was as at consultative sales.

As the new leader, I wanted to start things off in a big way. (Stay tuned for that part; I ended up getting more than I bargained for.) After securing the vice president’s approval and funding, I planned a two-day sales-strategy meeting. I organized the conference room, secured the catering, and hired Nancy Moore (one of our internal performance consultants) to facilitate a two-day training. My intention was to help the team get up to date on our latest leadership solution. Instead, most of them were getting their resumes up to date—but I’m getting ahead of myself.

On the morning of the first training day, Nancy and I arrived an hour ahead of the 8:00 start. I remember it well. I was excited and amped after one-too-many cups of coffee. (In fact, one was too many in Provo, Utah, where the predominant faith prohibits coffee drinking). But even highly caffeinated, I was invested in the team’s success. As was Nancy, who even brought a platter of beautifully arranged and freshly cut fruit for everyone (something she assembled herself, not one of those platters you buy ready-made from the grocery store). As I took in the final moments before my new team would arrive, I knew I was ready for my leadership debut. It was going to be epic! But when I saw the clock hit 8:00 and the room remained full of empty seats, my enthusiasm turned to anger. I watched the clock like a hawk, growing increasingly upset with each passing minute. Apparently, I had earned zero respect as their leader. It wasn’t until 8:15 that a few people began to stroll in. At 8:30, a full hour and a half after Nancy and I had arrived, the last associate showed up and the training began.

I was incensed. I managed to open the meeting, introduced the consultant, and took my place at the U-shaped table. But I was consumed with the perception that on my first day as their leader, the team would demonstrate such naked disrespect by being so cavalier about the start time. After all, we’re experts at time management; how could they all show up late and not even apologize? It stewed in me, and like most issues that irritate me, it metastasized and took on a life of its own.

I went through the day fixated on the obvious contempt my new team had for me and my role. And they knew I was annoyed because I made zero attempt to conceal it. The concept of self-regulation and managing my emotions was not even in my lexicon at the time.

It continued to agitate me into the evening and the next morning. On the way to the office, I stopped at the grocery store, not to buy fruit or croissants, but to buy ten copies of The Salt Lake Tribune. I had a plan, and it was going to be legendary. Leadership in action, people.

Let's just say I wasn't born with the humility gene. I struggled with it as a first-time manager, and I struggle with it now. I have to really work at remembering its value in my relationships, especially as a leader.

I entered the room at exactly 8:00 a.m., our starting time. To my sadistic delight, few were in their seats. Ten or so minutes passed before everyone was finally seated. I stood up, in what I thought would be one of my finest leadership moments, and began to walk around the table. I pulled the classified ads out and tossed them in front of each person, announcing, “If you want a job from nine to five, Dillard’s is hiring.” And in case they didn’t get the point, I passed out yellow markers so they could highlight any openings.

This was what being a successful leader was all about! I was making an important point and would reclaim their respect through my candor, boldness, and leadership strength.

At least, it seemed like a good idea at the time.

Rather than acknowledging my leadership genius, people began getting up from their tables and leaving. Many shot me looks that ranged from confusion to sheer repugnance. Still others began telling me off, more than one threatening to quit on the spot. So naturally, I did what any good leader would do under such awkward circumstances: I doubled down. This was on them after all, not me.

Maybe not the best strategy. Nancy stood frozen, watching in disbelief. One colleague announced it was his last day. There was a general theme to the complaints against me: How could this newly minted leader, the same one sponsoring a leadership-training session, so blatantly disregard the leadership principles being taught?

Calling that moment a management mess is probably kind. Because this was nearly twenty years ago, how we all managed to take a collective breath and salvage the moment is a bit fuzzy. I am sure it had more to do with them than me, but we somehow reassembled about an hour later and finished the day.

When you learn to embrace humility, you feel more comfortable because you know who you are. You can let go of the fear of making mistakes or the need to never show weakness. To quote our cofounder Dr. Stephen R. Covey, “Humble leaders are more concerned with what is right than being right.”

If you think I had a leadership mea culpa that morning, you’d be wrong. For days I privately insisted to Nancy that I was in the right. To her credit, she patiently listened to my absurd rationalization. A week or so later, she finally sat me down and helped me understand why my technique had not served me well. It was hard for me to see her point, but I trusted her to have my best interests in mind, and so took the lesson to heart. I did my best to make it up to the team and apologize for my actions.

You might be surprised to learn I’m friends with every person who was in the training room that day, including Nancy Moore, who remains a close mentor and confidant twenty-plus years later. Many of them came to my wedding a decade following the “incident,” and we laughed until we cried at the absurdity of it all. (Free-flowing libations no doubt helped.) In fact, several of them re-created the scene at my reception in front of my new wife of only 120 minutes. I’m sure she must have been worried that she’d just committed to a sociopath. In the end, we all marveled at my profound ignorance and arrogance.

Or said another way, my total lack of humility.

Let’s just say I wasn’t born with the humility gene. I struggled with it as a first-time manager, and I struggle with it now. I have to really work at remembering its value in my relationships, especially as a leader.

In my role as executive vice president for thought leadership at FranklinCovey, I am privileged to host several interview programs, both on the Internet and iHeartRadio. After interviewing more than a hundred bestselling authors, CEOs, and leadership experts, the one commonality they all share when defining a great leader is humility. They see humility as a strength, not a weakness. You might argue that the opposite of humility is arrogance. Through conversations with my friend Karen Dillon, former editor of Harvard Business Review, I’ve come to learn that humility is born out of confidence—confident leaders can become humble leaders. It is arrogant leaders who are incapable of demonstrating humility.

Leaders who fail to demonstrate humility often find themselves seeking outside validation. They rarely listen to anyone but themselves, and thus miss opportunities to learn and course-correct. They often turn conversations into a competition and feel the need to “one-up” others and have the final say.

In FranklinCovey’s bestselling book Get Better: 15 Proven Practices to Building Effective Relationships at Work, Todd Davis writes:

“Those who are humble have a secure sense of self—their validation doesn’t come from something external, but is based on their true nature. To be humble means to shed one’s ego, because the authentic self is much greater than looking good, needing to have all the answers, or being recognized by one’s peers. As a result, those who have cultivated humility as an attribute have far greater energy to devote to others. They go from being consumed with themselves (an inner focus) to looking for ways to contribute and help others (an outer focus). Humility is the key to building solid character and strong, meaningful connections.”

When you learn to embrace humility, you feel more comfortable because you know who you are. You can let go of the fear of making mistakes or the need to never show weakness. To quote our cofounder Dr. Stephen R. Covey, “Humble leaders are more concerned with what is right than being right.”