Читать книгу Once We Were Sisters - Sheila Kohler - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеII

TOGETHER

WE ARE BORN IN SOUTH AFRICA AND GROW UP TOGETHER IN an L-shaped Herbert Baker house, called Crossways, in Dunkeld, a suburb of Johannesburg. Pale jacarandas line the long allée that leads up to our creeper-covered house. The thick walls and closed shutters keep the rooms cool in the hot afternoons. The vast property, with its swimming pool and fish ponds, a tennis court, a nine-hole golf course, an orchard and vegetable garden, and acres of wild veld stretches out to the blue hills.

An army of servants keeps up the estate. Servants roll the butter between wooden slats with serrated surfaces until it forms small balls that are placed in shell-shaped silver dishes; they polish the silver, the furniture, the floors; they cook the roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, the two green vegetables and the roast potatoes; they simmer the inferior boys’ meat (“boys” being how we refer to our adult male servants) into a delicious-smelling stew; they stand in their thin white gloves, their soft silent sandshoes, and starched suits, a bright sash going slantwise across their chests, as they move behind the Chippendale chairs to serve dinner; they go out into the back patio to stoke the coal fire.

Sometimes gangs of convicts are brought in to dig and smooth out the lawns with heavy rollers, to weed the flower beds planted with bright cannas, foxgloves, and nasturtiums. My sister and I stand, holding hands, staring at the men in their striped shirts, their feet bare, digging with the evening light behind them. We listen as they sing in sad harmony before we are told not to stare, to move along, move along, girls.

We are always together in the pale green nursery where we sleep with our nanny—the blackboard along one wall and along the other side, the three beds, each with its green bedspread, a wooden bedside cupboard, and a round enamel chamber pot. We are together in the sun-filled breakfast room, where we swallow the thick porridge, the boiled mutton with caper sauce, the Marmite sandwiches with hot milk tea, the heavy English food that makes us sweat; we are together in the corridor with the Cries of London lining the wall—the series of prints showing nineteenth-century city vendors calling out their wares—and in the shadowy pantry with the pull-out bins for flour and cornmeal and the big bags of oranges that perfume the air. We are together in the sunshine in our identical smocked dresses, our sandals, our fair bare heads. We have identical Airedales, Dale and Tony, two big dogs with the same soft fluffy light-brown fur, who are not allowed into the house, but who roll around with us on the lawn and sleep in their kennels outside in the garden.

Together my sister and I explore the vast garden. We are left to roam in the sunshine, often barefoot, free to dream. We know all the flowers and trees intimately like the familiar characters in a favorite book.

They are part of our games, our imagination. They are half real, half made-up, part of our fantasies and our reality, our transitional objects.

We smash mulberries on our faces for war paint and play Cowboys and Indians. We climb the jacaranda trees. They are all good except for the last one on the left, which is wicked, and which we avoid assiduously. We set up a pulley between our respective trees and send it back and forth with little notes written to one another, though I cannot yet read or write properly, and we can call out to one another much more easily.

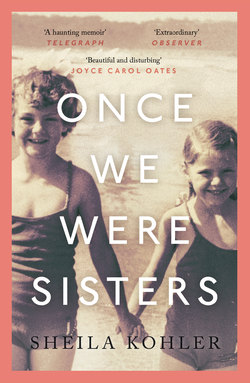

Maxine and me in the garden at Crossways.

We make up our own secret language, a complicated system of spelling backward: “cat” is “tac,” though there are few words I can spell, and I keep forgetting the rules.

We give our identical dolls swimming lessons, tying string around their rubber waists and dragging them up and down the pool, instructing them to kick. We lie on the concrete around the pool in the sunshine and play the game of Touching Tongues, giggling. A bee stings me while we are doing this, and our nanny tells us this is what happens to naughty girls.

I sit in front with my sister behind me, her legs around my waist, using our hands as paddles sailing around the big enamel bath, with its claws for feet, visiting foreign countries, going “overseas,” traveling around and around, splashing the water on the black-and-white-tiled floor.

We whisper together in the shadows in the back of the nanny’s square green Chevrolet. “Let’s make a bunch,” I say, and together we slip off the seat, crouch down, and strain, producing a small malodorous gift for the nanny. We run down to hide in the bottom of the garden, terrified at our wickedness.

We climb the stile and hide down in the wild part of the garden, listening to the wind in the swaying bamboo. We play the secret game of Doll. Alternately Maxine is the “doll,” lying stiff and obedient to my wishes, or the mistress, who makes me do whatever she wants me to do.

It is this game I think of later, when the Roman men call out to us, “Che bambola!” What a doll!, and much later still, when I see my sister, her shattered body wrapped in white as in swaddling clothes.