Читать книгу Once We Were Sisters - Sheila Kohler - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

IT IS FIFTEEN YEARS BEFORE MANDELA BECOMES PRESIDENT, and South Africa, a country I left at seventeen, is still in the grip of apartheid. It is my thirty-eighth year. It is October, which the Afrikaners call die mooiste maand, the prettiest month, our spring.

My mother calls with the news. My brother-in-law, a heart surgeon and protégé of Christiaan Barnard, the first doctor to transplant a human heart successfully, has managed to drive his car off a deserted, dry road and into a lamppost. Wearing his seat belt, he has survived, but my sister was not so lucky. Her ankles and wrists were broken on impact. “She died instantly,” my mother assures me. I wonder how one knows such a thing and think of that moment of terror in the dark.

I take a plane out to Johannesburg and go straight to the morgue. I am not sure why I feel I must do this. Perhaps I cannot believe my only sister, not yet forty years old, the mother of six young children, is dead. Perhaps I believe the sight of her familiar face and body will make it clear. Or perhaps I just want to be beside her, to hold her one last time in my arms.

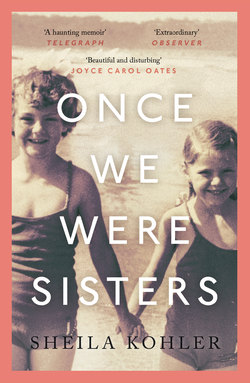

I stand waiting with my hands on the glass, looking into the bright, bare, empty room with the sloping floor made of reddish stone, which dips slightly in the center to provide drainage from the dissection table. Then they wheel her body in. I cannot touch her, hold her, comfort her. I cannot ever heal her. Her whole body is wrapped in a white sheet, only her flower-face tilted up toward me: the broad forehead, the small, dimpled chin, the slanting eyes, the waxy skin. It is my face, our face, the face of our common ancestors. It is the heart-shaped face she would turn up to me obediently when, as children, we played the game of Doll.

This moment is the beginning of endless years of yearning and regret. It is also the beginning of my writing life. Again and again, I will turn to the page to recapture this moment, my sister’s life, and her spirit.

With her death, too, comes a flood of questions. How could we have failed to protect her from him? What was wrong with our family? Was it our mother? Our father? Was it our nature, the way we were made, our genes, what we had inherited? Or, more terrible still, is there no answer to such a question? Was it just chance, fate, our stars, our destiny? It was not as if we did not see this coming. What held us back from taking action, from hiring a bodyguard for her? Was it the misogyny inherent in the colonial and racist society in the South Africa of the time? Was it the Anglican Church school where she and I prayed daily that we might forgive even the most egregious sin? Was it the way women were considered in South Africa and in the world at large?

I am still looking for the answers.