Читать книгу Once We Were Sisters - Sheila Kohler - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIII

FIRST GLIMPSES

IN NEW HAVEN MY SISTER HOLDS MY NEW BABY GIRL UP IN the air and admires her dark slanting eyes. Maxine says she is beautiful. She props the baby’s head over her shoulder and pats her back and tells me about the man she has just met, who wants to marry her.

We have both laughed at, flirted with, and danced with many different boys.

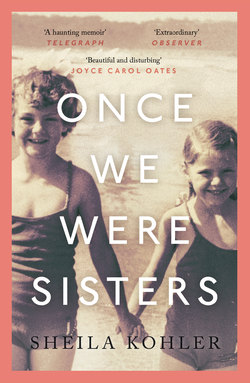

In Johannesburg we were known as the Kohler girls: Maxine, the elder one, the sweet one, with her soft blond curls and long-lashed violet eyes, her pale delicate skin that bruises so easily, the shy smile; and Sheila May, two years younger, darker-skinned, with straight hair, gray-green sloe eyes, and narrow, boyish hips.

Maxine is the one who never suffers from spots, the one who is said to look “like an English rose.” She is dreamy, good-natured, and merry. Her kindness does not mask her intelligence, but it is obvious her sympathy comes first. She seems placid, but as with a calm sea on a sunny day there are sudden squalls.

I torment her in the nursery by touching her bed with the tip of my finger, which I know annoys her. I lean across from my bed and poke. “Please don’t touch my bed,” she says again and again, “please don’t touch my bed,” and finally, when I continue to laugh and touch the bed, she throws the glass of juice she is drinking in my face.

When we fight as children in the back of the car, Mother suggests we both get boxing gloves.

“I hate her,” I tell Mother in a rage.

“No, you don’t, you love her,” Mother says.

I do, I do.

Maxine laughs and cries easily, her big eyes quick to fill with tears at a glimpse of someone else’s sorrow. She will pick up someone else’s baby on the beach, if it is crying. She is the musical one, the one who learns the Mozart sonatas and plays with feeling, the one who gets the Steinway, when Mother takes it out of storage. When I try to play nursery rhymes to my children on the piano, they will run away.

We are both readers, curious about people, the past, and above all, about love.

Now Maxine holds my baby, Sasha, in the Viyella night-dress with the drawstring neck, that my mother and sister have brought into my small room in the Grace–New Haven Hospital in a carry-cot filled with clothes for my baby to wear. She tells me about the young doctor she has met in Johannesburg. I am not sure how much she tells me that day, or even how I react to her words. I am unaware of their importance in our lives. I am preoccupied with my new husband, my new baby, and with the blood that flows from my own body. Much later, her children will fill in the blanks with words that ring with significance.

She has caught a first glimpse of Carl at a tennis party in Johannesburg. He is playing tennis, hitting the ball hard in the sunshine. She finds him dashing in his tennis whites and is, her son later tells me, “immediately smitten at the sight.”

At twenty I have already married the American I first glimpsed at nineteen standing in the shadows outside our ground-floor flat in Rome. He was slouching slightly in the dim light, before the iron gate in the Parioli. A long, lanky twenty-year-old with high cheekbones and a blond forelock that tumbled into his slanting eyes, he was slim-hipped in his blue jeans, the white shirtsleeves turned up to the bony elbows. He was ringing our bell in Rome. I stood hesitating in the twilight, my hand on the ornate wrought-iron gate. Grinning his big baby grin, he announced that he was the friend, Michael.

“Enrico’s American friend,” he said. So I let him in the door and eventually into my bed and then into my heart, my heart of hearts. He has become my conduit into life as my sister was once.