Читать книгу Once We Were Sisters - Sheila Kohler - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIV

SUITORS

NOW MAXINE TELLS ME SHE, TOO, IS THINKING OF MARRYING.

“But what’s he like?” I ask.

He is a blond and blue-eyed Afrikaner who grew up in Ermelo, a small town in the Transvaal, and his father works as a superintendent on the railways, or perhaps she says he is a caretaker of gardens. He seems to like flowers. Carl’s mother’s name is Azalea, which does not suit her at all, I will think, when I meet her years later. There is nothing flower-like about Ouma, as we will call her—using the Afrikaans name for grandmother—a large, solid lady with a heavy hand. Her youngest son, Louis, will say much later that his mother tried with increasing bitterness to get her children to continue to speak Afrikaans by taking them to the Dutch Reformed Church, something they resisted. English has become their language, the language of what Ouma probably considers the oppressor.

Carl, a nerd at school with thick-rimmed glasses, one of his daughters will tell me later, had been teased as a boy. He passed his matriculation at sixteen and is already a doctor at twenty-one.

“I don’t think he’s had time to read Dostoyevsky,” Maxine says and laughs.

My sister and I have sworn we will never marry anyone who has not read Dostoyevsky. We have copied out long passages from Ivan Karamazov’s speeches about the existence of evil in the world into our black hardback notebooks.

“And what about James and Tom and Neville Rosser?” I ask. She laughs and strokes the soft fair fluff on my baby’s round head.

I know my sister, at twenty-two, has seriously considered several suitors: James, a good-natured South African who owns a large banana farm with blue trees and many big dogs in Natal; Tom, a slim, fair Scot with curly hair, who wants to become an Anglican priest; and Neville Rosser, who took her to the school dance, and who has glossy black hair, a dimple in his chin, and will become an engineer and even find oil in his backyard, I find out later.

Then there is Henry, the distinguished Englishman, the member of the Grenadier Guards, the son of a friend of Mother’s who took Maxine out the night of her presentation to the Queen, she tells me.

My sister dropped a curtsy before the Queen in a pale mauve, pleated dress with a décolleté that showed off her smooth young skin, and a little mauve pillbox hat that perched on the back of her blond curls.

Mother, who is friendly with the wife of the South African ambassador to England, Harry Andrews, had my sister’s presentation arranged, though Mother’s accountant, a Mr. Perks, who manages our money, protested. He considered a presentation to the Queen would encourage her to “live above her station.”

My mother, like many white South African women, rarely speaks of politics, hardly reads the newspaper, or only the kind with headlines like “Monkey Steals Baby from Carriage,” but anything about the English royal family, on the contrary, has an almost sacred glow. She reveres the Queen, who has been so brave, she says, during the war, the Queen who will become the Queen Mother in 1952.

We were even taken to see the royal family, including the two princesses, in 1947, Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, when they came out to South Africa for a visit. I remember the crush of the crowds and a terrible moment, when my sister let go of my hand, and I was lost for a few moments of panic.

I still have a photograph of Maxine in her presentation dress on my bedroom wall, and sometimes people ask me if it is a photo of me, which makes my heart tilt with sorrow. There is something so unworldly about her with the cloud of light behind her head, a misty English countryside suggested in the background. She sits there in her ethereal loveliness in her pale mauve dress with the pleats, a curl on her forehead, her shy smile. Why did I not sense she would escape us all? Why did I not see how soon this would be, and how tragic?

I remember how my sister told me Prince Phillip, poor man, looked very bored at this endless procession of young girls, peered down the front of her décolleté to get a glimpse of her smooth breasts.

After the presentation she was asked out by this young Englishman who invited her to his flat. At his door she made the embarrassing error in etiquette of shaking hands with his batman, a sort of superior servant of an officer, she tells me.

She has told all these suitors she will make up her mind soon. Now she has met someone new, which adds to her confusion. She often has difficulty making up her mind.

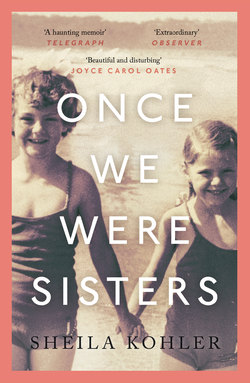

Maxine in her presentation dress.

“Mummy’s against it,” my sister says, smiling ruefully. She holds my little girl so lovingly against her shoulder, her hand on her head. My sister loves babies.

“Why? A handsome doctor, and you always said you wanted to be a doctor yourself,” I say.

“Well, the Afrikaans background, though he speaks perfect English—and you know what she thinks of them, going around saying they beat the natives with a sjambok and commit incest on their deserted farms.”

Mother maintains her grandfather was a Russian nobleman, whose land was usurped by a wicked uncle. He had to leave his vast estate, his serfs, the forests of white birch, and flee his country. He wandered through many lands, learning the twelve languages, not including the native ones, which he supposedly spoke. Passing through Salonika, he adopted the name of the place and came out to South Africa. I will later discover he started a grocery store there, though Mother leaves this less-glamorous part out of her story.

Was he perhaps a Greek? I wonder, later in my life, seeing the picture of the dark-haired merchant, standing outside his store, his apron tied around his waist, surrounded by his large family. Wherever her family came from, Mother looks down on the Afrikaners, the Boers. She considers them uncouth and, though she herself has never finished high school, uneducated. She makes fun of their simple guttural language and cites their translations from the Bible with derision. She maintains the Afrikaans translation of “Gird up your loins” is “Maak vas jou broek,” which makes her laugh because of the sound of the simple words. Since the bitter Anglo-Boer War at the start of the twentieth century, there has remained great enmity between the two white tribes.

My sister says the family is quite poor. Carl is the only one who seems to have succeeded so brilliantly, thanks to a good brain, a capacity to focus on the task at hand, and hard work. There are innumerable brothers and sisters, and a niece will later tell me his mother, Azalea, would run after them and beat them all hard with a hairbrush.

“The mother is rather plump and wears terrible hats. You know what a snob Mummy can be,” Maxine says.

“Do you love him?” I ask.

“I like how frank he is with me, that he tells me the truth, says what he thinks. It’s refreshing,” she says.

“I know what you mean,” I say, smiling at her, thinking of how we have both scoffed at all those “nice” boys our mother has introduced us to, all seemingly called Cecil or Montague. We don’t give much weight to Mother’s opinion on the subject of marriagable men, or indeed on anything else. On the contrary, we are open to others, ready to take a chance. We both know that Mother, who has not had the privileged childhood we have had, nor the education, feels it is important to marry someone wealthy and live in a large house with many servants as she has been able to do.

When I tell Mother I would like to be independent, to find meaningful work, she stares at me blankly and says with genuine surprise, “What on earth would you want to work for, dear?” Much of her life has been a successful struggle to avoid any work.