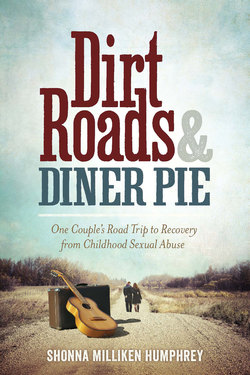

Читать книгу Dirt Roads and Diner Pie - Shonna Milliken Humphrey - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

Push Away the Blanket

“I need for the Boychoir to not take up so much space in our life,” I said on the night before our trip. It felt like an ultimatum, but I knew it was an empty one. With fourteen years invested, and a genuine affection for this man, I had no “or else” plan.

However, childhood sexual abuse affected our conversations, our family interactions, and our physical health. Our marital routine had become a slow mental drag, and it was hard to sort a typical ebb from the sinister undercurrent. Communications read like boring interview questions. Did you remember to feed the cats? Do we have enough money in the account? Can you get the mail? Did you sleep okay?

That last one, the sleep question, was the biggie. It plagued us. Since the early days of our marriage, Trav had battled night terrors in a cycle of not sleeping, being afraid to sleep, sweat-inducing nightmares, and then more not sleeping. He regularly shakes himself upright in our bed, and sometimes he screams.

“It stresses me out when, every morning, you ask if I slept well,” he eventually confessed. “I will never sleep well.”

I nodded as if I could possibly understand and promised to limit that topic.

I do not remember who made the decision to spend four weeks in pursuit of Americana and creative inspiration while leaving the snow-filled, icy Maine February behind us, but we agreed it was a good idea.

My hope was to shift the energy between us and push a reset button. What felt like the millionth pharmaceutical approach to his sleeplessness seemed to be helping, and I wanted to rid ourselves of distractions, get on a consistent schedule, forget work, and eat good food. I wanted to remember why I chose to spend my life with this man, and most of all, I wanted to not think about the Boychoir every single day.

“I am serious,” I said. “This trip will make or break us.”

Still, on our departure morning, I could not get out of bed. The house felt strange with our travel items neatly packed by the door and the smell of furniture polish permeating the freshly dusted room.

“I don’t want to go,” I whined from underneath the blankets. Anxiety levels rose in my chest, and I ran down the scenarios in my head: The house could burn, my sister might need me, our parents could get hurt, or the cats could die. Fear was a choker around my neck, and I tried to mitigate the fear with rational thoughts.

From under the covers, I remembered the last time we had traveled. It was to California for a wedding, and on our last day in San Francisco, Trav paced the hotel room in anticipation of the return flight. This pacing happens every time we travel. Any situation that removes control—particularly losing all control during the heat and swell of the airport, the tight and claustrophobic squeeze into the plane, and sitting immobile for several hours in flight—is a misery for my husband. Many people do not enjoy flying, but for Trav, the panic is more sinister.

It taps into time he spent as an American Boychoir student that was filled with unfamiliar and dangerous experiences, unreliable adults, and a need for an extreme level of hypervigilance to protect himself.

We had ten hours until departure, so I suggested we drive through the city and visit Golden Gate Park’s Japanese Tea Garden. He loves spaces with positive, Zen-focused energy.

Something to offer him control, I have learned, works well. Focusing on the car, the streets, and the directions helps. But on that day, Trav gripped the steering wheel, his triceps tight.

Despite the peaceful nature of the lush space, Trav could not focus. He had no energy to traverse the inchworm-like wooden bridge or contemplate the fat orange koi, and had no appetite for a teahouse snack. We burned time with some stale éclairs at a neighborhood bakery.

“Can we please just go to the airport and get it over with?”

By then it was noon, and our flight left at 8:00 P.M.

I dosed Trav with an antianxiety pill in the car rental return area, and then another in the terminal. Tucked way back in the farthest corner so no other passengers could see his shaking, he drank whiskey at the airport bar.

When I handed him two antihistamines just before boarding, he asked for three.

For the next six in-flight hours I watched his rigid body, face forward and clinging to the armrests.

That is my job, I often think. Watching Trav. As a performer, Trav gets paid to have people watch him, but I was sick of the task.

Once so optimistically planned, on the morning of departure this road trip felt like a month-long slog of watching Trav, caring for Trav, and participating in a Trav-focused parade of Trav-issues. I felt unequipped for the task.

But our dog had been delivered to my in-laws. Trav’s sister would feed the cats. The contractors intended to use our time away to remodel the rotten bathroom in our 1961 Cape. The basement mold-abatement estimate came in, and the company promised to start work as soon as we returned.

Plans had been made, and Trav packed the van while I shrugged off the quilt.