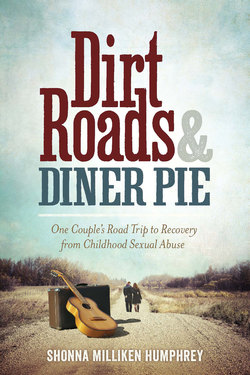

Читать книгу Dirt Roads and Diner Pie - Shonna Milliken Humphrey - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER SEVEN

No Escape from New Jersey

If the American Boychoir School’s myopic approach was limited and restricted to a single individual acting as an interim representative, I could better understand, but these attitudes extend well beyond a single person, and cultural entrenchment is harder to address. Cultural entrenchment extends beyond a single school, and it affects any organization dealing with repercussions of child sexual abuse.

Alumni, students, faculty, constituents, and administrators must believe in the value of institutions facing child sex abuse allegations because to shift that perspective—however slightly or with compassion—means a shift in responsibility. That shift requires revising not just institutional policies, but institutional philosophies.

It is much easier to dismiss sex abuse as experimentation among peers or an anomaly limited to a few deviant adults, and this dismissive mentality or “us versus them” perspective leaves no room for broader cultural constructions or, most importantly, the victim’s experience.

For instance, the mother of an American Boychoir School student sent me a note. She had read my published essays about the abuse Trav endured while attending the school, and she opened with an attempt at compassion.

“I am sorry this happened to your husband,” she wrote to me, never, I noted again, doubting the accuracy of Trav’s account. Instead of stopping with that concern, however, she immediately added a series of familiar conjunctions.

But it happened so long ago. But so few boys were molested. But the school is a much better place now. But there are policies. Those “buts” skipped over the victims so quickly, I am not sure she noticed. She called my portrayal of the school unfair and explained that her son’s experience had been only positive. Her message—another script heard regularly by victims—was clear: Stop talking about it. Move on. Why spoil it for the rest of the boys?

“I am glad her son was not molested and raped,” Trav told me when I shared her words. “Some of my friends and I were.”

He continued, “Both things are true, and my experiences are no less important than her son’s.”

Now, in the midst of a massive fund-raising push (as of this book’s writing), among the school’s biggest arguments for continued support is nostalgia—that we, as a community, should not forget the school’s impact and significance. And all those beautiful young voices.

But this is exactly what the school asks of its victims: Forget. Go away. Your once-heralded voice is no longer important.

This approach shuts down a conversation.

The mother extolled the school’s positive impact and attached a photo of her smiling son as proof. She closed by inviting my family to attend the school’s holiday concert as her guest.

My response, a sharply worded and unkind email, requested that she read her words aloud, and then continue reading them aloud until the cruelty and stupidity of those words set in. Choral music is a trigger that could easily send Trav into a funk that might take a week to emerge from, and the prospect of literally applauding the organization while sitting powerless in the audience would reinforce the memory of every time Trav was forced to smile and perform as a boy.

When I read her words to Trav’s dad, his response was even more direct. “Is she kidding?”

Her note was not malicious, but it was thoughtless and unintentionally cruel. Like the acting school representative who spoke with me, this mother believed the school’s messaging. To think otherwise would shake her foundation as a parent. Like that administrator, she had to believe her son was protected and her family immune.

I also noted in my response that Trav began drinking coffee at age eleven, so he could remain alert and vigilant at night.

“Does your son,” I asked for a comparative reference, “drink coffee for this reason?”

As more and more institutions confront the unenviable task of responding to newly surfaced childhood sexual abuse allegations, there is much to be learned. For decades, the American Boychoir School, and others like it, have prioritized protecting the institution over caring for survivors of abuse perpetrated within the institution. Until that perspective shifts, I suspect this reputation for the child sexual abuse itself—as opposed to how the victims were treated—will persist.

These are the thoughts that occupied my mind in the last few moments of the van’s hurried push toward the New Jersey border. My shoulders had tensed up, too, and the paper cup held in my hand since Maine was now a crumpled ball of damp cardboard.

Timelines for institutional atonement are complex, but I imagine the levels of possible healing would be great if the American Boychoir School officials (and others in charge at other institutions) changed the narrative and approached accusations of sex abuse from an initial position of compassion, with a simple “How can we help?”

Trav’s suggestions would be direct. First, accept institutional responsibility. Next, provide a clear path for victims to access resources. Finally, be an innovative, collaborative voice in the conversation.

Or, if that feels too big and weighty a job to tackle, he would suggest starting with punctuation basics. Instead of compound sentences and conjunctions, use simple sentences. No more “I am sorry this happened, but . . .”

“I am sorry this happened.” Period.

Anything else is the same old message.