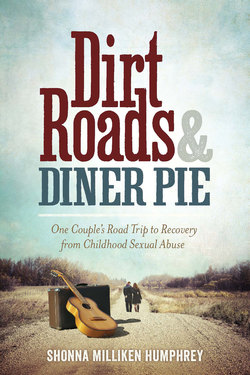

Читать книгу Dirt Roads and Diner Pie - Shonna Milliken Humphrey - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

First Corinthians

The drive south from Maine is ugliest in February. Any brief peek of ocean shows it foamy with garbage. Roadside snow is hard packed and covered by sand, ice, and gravel. Rather than offering sun-soaked summer blue-water views, Maine moved through New Hampshire and into Massachusetts via a constant screen of crumbling-brick mill smokestacks with clusters of vinyl-sided houses standing close to the highway.

I wondered about those houses and whether the highway came first and the homeowners received a special incentive to build, or the houses were grandfathered in tight when the highway was made. Apartments were stacked on top of each other in the multiunit structures, and squat ranches and awkward split-levels represented the single-family houses. After taking a mental note to research the highway’s history, I quickly forgot.

To pass the first day of drive time, I made up elaborate stories about the occupants of those homes visible from the highway, imagining torn linoleum kitchen floors, the smell of heavy diapers, and mothers cooking generic boxed macaroni and cheese for a crowd of dirty-faced children. After passing house after house with cracked, mint-colored siding and broken plastic toys strewn across the frozen mud-and-snow-covered yards, I stopped with the character development because all my stories were sad.

We drove past gray-and-brown strip mall backsides, too, in differing states of decay, as well as half-done construction projects with massive piles of dirt and idle yellow equipment.

I wanted to note something beautiful, like stark, bare tree branches resembling lace with their bent limbs and intricate patterns against the clouds, but it was just a gray-and-brown road blur against gray-and-brown structures under a gray-and-brown sky.

A hot-pink Dunkin’ Donuts coffee-mobile car pulled up beside us and broke the view of dull highway, and the driver waved at me from the next lane. I waved back through the window while sipping hot tea and thinking about omens and luck. That bright pink car with its oversized Styrofoam cup-shaped attachment seemed like an omen: frivolous and happy. Trav and I had the entire month of February to check out, move off the grid, and find sun. That felt like the best kind of luck.

We had saved money for this trip, and each Sunday that we shared pizza instead of sitting across a cloth-covered table spread with briny Damariscotta River oysters or a big bowl of savory Tsukimi Udon, I imagined the savings buying us Nashville biscuits and New Orleans beignets. Now that we were officially on the road, I dug into the bag of sliced green apples from the snack box between our seats and balanced my boots on the dashboard.

“You are patient,” I said to Trav on that first day of driving, and I still do not know what prompted that observation. He is, though. It is a trait I do not share. Trav can step back, smile, and assess a situation with a sense of perspective and comfort.

“It is adaptive,” Trav answered, but I disagreed.

“I think it is innate.”

I watched Trav’s face as he drove, and I watched his body, too. Had I not been present, his approach would be more aggressive, and I appreciated his effort to drive slower and with more deliberation, a nod to my comfort, as the traffic got thicker.

He handles vehicles well, and his steady hands rested on the bottom of the steering wheel after pulling a pair of aviator sunglasses from the pocket of his well-worn hooded sweatshirt. The highway billboards—illegal in Maine—popped up in abundance as we sped through Massachusetts. The initial set advertised junk cars for sale, then an Army recruiting station, and when the first religious message appeared, it was a Bible verse.

First Corinthians. “Love is patient.”

Having just noted Trav’s patience, I thought this, too, seemed like an omen.

Trav laughed when I said I preferred the alternative translation of “Love suffers long.”

“Semantics,” he said.

It felt like a good sign.