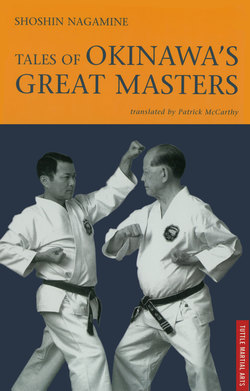

Читать книгу Tales of Okinawa's Great Masters - Shosh Nagamine - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

MAKABE CHOKEN OKINA:

A MAN OF GREAT STRENGTH

THE DIVINE JUMPING TECHNIQUES OF TOBITORI

There was a hospital owned by Taira Masa which was situated in Shuri’s Tounukura district before the war. This was the same site where the Makabe estate once stood. Makabe’s residence covered an area of 360 tsubo (1188 meters) and many kinds of budo training equipment were located there. Makabe Choken Okina is said to have trained there every day. Thanks to the Taira family, I enjoyed the privilege of inspecting a footprint on the ceiling of the guest house, put there, rumor maintains, by Makabe himself while demonstrating a jump kick. I went there with the interest of confirming it with my own eyes. Using my eye to compare the height of the ceiling in this old style residence to those of other Okinawan-style homes, I would say that it was over four meters high.

Portrait of Makabe

Makabe Choken was born the fourth son of Makabe Aji Chougi (whose Chinese name was Jigenho), during the time of King Shoboku. Choken’s childhood name was Umijiru and his Chinese name was Koubunbin. He grew quite large during his youth and by the age of fifteen or sixteen, he developed into an enormous man of muscle.

Coming from a family of wealth and position, Makabe received a good education which, during Okinawa’s Ryukyu Kingdom, was referred to as Teshimi Gakumun: te means “hand” but implies martial arts, shimi means “calligraphy” but implies a scholarly pursuit (i.e., the study of Confucianism), and gakumun means “to study.” Together, they represent the principles of bun bu ryo dō: the significance of balancing physical training with philosophical study. In addition, Makabe also became familiar with Japanese academic pursuits.

In spite of Makabe’s well-known reputation as a bujin, who trained him and in what tradition remains the subject of intense curiosity. Notwithstanding, it would seem that whoever was responsible for his education did a remarkable job.

Makabe was respected as a talented man, with a good physique and remarkable power. During Makabe’s youth there were other strong young men who challenged him. One young stalwart was a man named Funakoshi. Funakoshi had gained a reputation as a brave strong fellow after pinning a fighting bull to the ground by twisting its head and holding it down by the horns.

The confrontation was held on the grounds of the Makabe residence. In preparation for the bout several shiijakata (referees) and a horde of excited young men had gathered in the courtyard to observe the exhibition. First the contestants were required to demonstrate their strength by lifting a ninety kilogram chikarasaashi (old style stones used in power training, similar to today’s barbells). First Makabe, without much effort, did twenty quick presses over his head before putting the apparatus back down on the ground. The audience remained collected as they knew Makabe trained every day. However, when it came time for Funakoshi to attempt the lift there was a pause. He was unfamiliar with the equipment and the conditions were different from what he was used to, and the audience sensed it too. Yet, in spite of the variations, Funakoshi attacked the chikarasaashi and rattled off the same amount of repetitions as did Makabe. The crowd was astonished by Funakoshi’s power and immediately showed its enthusiasm.

Illustration of the chikarabo bout.

Next came the chikarabo, a game which tested the power, balance, and dexterity of its participants. It required each contestant to brace the end of a bo on a point just below the umbilicus (the tanden) and hold onto it with both hands. Thrusting at each other while keeping the posture in a pliable but authoritative position, victory depends entirely on a keen sense of positioning. Weight and strength are not enough to win. Just like budo, knowing the principles of taisabaki (body movement), and kiaijutsu (the build up, containment, and release of ki) had to be mastered in order to overcome any opponent.

Still intact after about an hour or so, the shiijakata ordered the contestants to change position. Once again they vigorously went at each other but to no avail. Finally the shiijakata declared the bout a draw, it was just too close a game. All but burned out, Makabe and Funakoshi took a rest for a while before starting the next event to settle the contest.

Agreeing to test their tobigeri (jumping kicks), the next event finally got under way. The location was changed from the courtyard into the guest house of the Makabe residence.

The guest house of the Taira residence. Photo from the Ryukyu Kenhoshi.

Committed from youth to a life of budo, Makabe Chaan had more than adequately trained his running and jumping skills. He believed that the essence of combative superiority existed in pliability, not in stationary postures, and Makabe found Mt. Hantan, and Mt. Torazu ideal terrain for strengthening such skills. The Taira family maintained that whenever Makabe returned home late at night, like a ninja, he would jump over the stone gate which surrounded the residence so as not to disturb his family. The umoteyaajou (front gate) was the symbol of an Okinawan kemochi (those with a chronicled lineage; the equivalent of a Japanese samurai family) during the Ryukyu Kingdom period. However, the gate, like so many other treasures of Okinawa, was destroyed during the war.

The gate of the Taira residence. This photo originally appeared in the Ryukyu Ihoshi.

Generally speaking, a big man is usually strong but lacks mobility. However, Makabe Chaan was the exception to the rule. Incidentally, the suffix Chaan is a term which refers to a small, quick, and brave fighting cock. Hence, this nickname has led many to erroneously believe that Makabe was a small person.

In 1944, Makabe Chosho, a sixth generation descendant of Makabe Chaan, visited me at my request. The owner of a tea business in Naha’s Higashi-machi, he was kind enough to provide me with the family genealogy. His assistance was of enormous value to my research. However, my analysis along with his family records were unfortunately destroyed during an air raid on October 10, 1944. I am deeply sorry that I was unable to take better care of the Makabe family records.

Helping to corroborate Makabe Chaan’s actual size, Chosho-san recounted a story which I would like to impart. There was a kimono made from bashofo (bark from the bashoo tree). It was Makabe Chaan’s special keepsake from Amami, a principal island in the Ryukyu Archipelago, and was well cared for and handed down in the family. Although Makabe Chosho was an average size man, the kimono was, however, too long for him, even when he stood on the top of thick chess board. Although a minor point, it does, nonetheless, tells us that Makabe Chaan wasn’t a small man, as some would have us believe, but was more than six feet tall.

Makabe Chotoku, the vice president of the Ryukyu Fire Insurance Company, is a seventh generation descendant of Makabe Chaan. When Chotoku was rebuilding the family grave site after the war, he inspected Makabe’s bones. He said that he was surprised to see that his leg bones were so long. I believe that the information which I received from Taira, Chosho, and Chotoku, would all seem to indicate that Makabe Chaan was indeed of more than just average size.

To continue with the confrontation between Makabe and Funakoshi, there is an abstract poem which I believe characterizes their encounter.

Poem:

Bushi no miya, sura ni

tobu toi no kukuchi,

michimiteinteiniya touiyanaran

Interpretation:

The movements of a real bushi are not unlike those

of a bird in flight: swift, natural, and without

thought. Regardless of one’s physical strength,

catching a bird is virtually impossible.

Although Makabe was big and powerful, he was also unusually agile, no doubt the result of his intense training. Seemingly, Funakoshi dung to the idea that power was enough to overcome an opponent. He had successfully stalemated Makabe in the tests of power, and believed that he was ready to challenge the technique of the great bushi.

Now came the opportunity for Makabe to test the results of his lengthy training in jumping techniques. He took his stance as he prepared to unleash his kick. Looking calmly up at the ceiling of the guest house Makabe wasted no time springing into position before leaping up, and, with an enormous kiai (spirit shout), executing a jump kick as fast, and higher, than anyone in that room had seen before. Landing back on the tatami mat, Makabe finished his kicking demonstration in the meikata posture (an elegant position used in Okinawan folk dancing to music during village festivals). As the spectators stood in awe, the imprint of Makabe’s foot, remaining clearly visible on the ceiling, served to remind everyone of the incredible feat they had just witnessed.

When it came time for Funakoshi to perform, it remained obvious to Makabe that he was flustered. Having never even seen, let alone practiced, a jumping kick, Funakoshi scrambled to learn. Attempting to duplicate that which he had just observed, Funakoshi, in spite of Makabe’s friendly advice, fell flat on the back of his head, unconscious. By the time the fallen Funakoshi finally came to, he realized that he had been outmatched and, as was often the case in those days, asked Makabe to become his teacher.

A HEROIC EPISODE

During the Kingdom period, the ayajou-uugina (tug of war) was always a spectacular event in the old castle town of Shuri. Supported by the people of Mitara district, and authorized by the sanshikan (top three ministers in office), the tug of war was an event held primarily for Okinawa’s kemochi. The rope used in Naha had a diameter of three shaku and each side measured thirty ken (54.54 meters) in length, for an overall length of sixty ken (109.08 meters). The rope used in Shuri was twice the size of that used in Naha, and measured a magnificent 120 ken (218.18 meters) in length.

An event not taken lightly, the tug of war was a contest governed by strict rules. According to Naha City Magazine, the tug of war committee consisted of a buuhai (head of tug of war), chinahoo (maker of the rope), teehoo (maker of the lanterns), shitaakuhoo (maker of the costumes), chinkuhoo (conductor of the music), kanichihoo (maker of the wooden bo), suneehoo (chief of the parade guards), and hatahoo (maker and coach of the flags).

As previously explained, the ayajou-uugina was a popular cultural event which always attracted a crowd of people ranging from local government and satsuma officials, to kemochi and mukei (those without chronicled lineage). Because it was the most spectacular event in the Ryukyu Kingdom, participation in it was the ambition of all the young men from Shuri’s Mitara district. The holding of the flag and the kanuchiyaku (the staff) was considered a special honor, customarily a privilege reserved only for brave and bold men. A man selected for one of these roles was considered to be not only a man among men; he was truly revered.

It came as no surprise to learn that, in representing the east, Makabe Chaan was always selected for such positions since he was tall, powerful, and popular. The flag for the west, representing the opposition, was often held by Morishima Eekata, a man of Herculean strength. Morishima later had a son who became known as Giwan Choky, a prominent statesman, who died in 1875.

The shitaku (costume) for the east was designed after the historical boy samurai Ushiwakamaru (actually Minamoto Yoshitsune’s childhood name), while the shitaku worn by the west represented Benkei (a subordinate of Yoshitsune’s who dressed like a monk). With a first swing of the flag, the tug of war commenced and the ringing of the bells and drums became intense. After a superb kanuchibo demonstration, the participants gathered around the rope to engage each other. The grunts and shouts of physical exertion filtered through the music and commotion as an excited throng of spectators swarmed the venue. Yet, in the end, the game belonged to the east. Makabe’s team had emerged victorious.

The tug of war as shown in the Ryukyu Ihoshi.

As was the custom, the first and second flagsmen led the winner’s side around while the champions rang the bells, beat the drums, screamed feverishly in triumph, and danced around in high spirits. Regulation demanded that the losing team should quietly place the head of their flag on the ground and retreat in defeat.

The hatagashira (head of the flag).

However, at this particular event the west, representing the hatahoo (the vanquished), were poor losers and forgot their etiquette. Refusing to surrender their icon, they kept screaming and sailing the defeated flag in an effort to taunt the champions. Just as everyone began to notice what was going on, Makabe jumped into the midst of the defeated team like a flying bird, grabbed the flag and threw it to the ground and then withdrew without recourse. The audience, as well as the other team members, were overwhelmed by his bravery.

In old Okinawa, high ranking kemochi often used a palanquin to travel around. Not being immune to the problems of highway robbery, Makabe Chaan was well-known for his innovative techniques of defense and escape. One night there was a palanquin traveling through the dark streets of Shuri. The two palanquin holders suddenly felt apprehensive because the weight of their passenger had mysteriously vanished. When they put the palanquin down to check inside, it was empty. They were dumbfounded. All of a sudden they were overcome by fear as a black shadow jumped out from behind a well by the street. Without delay the two palanquin holders ran off in fear of their lives. Just then a voice yelled out, “Don’t be afraid men, come back.” Laughing quietly to himself, the voice was that of Makabe Chaan who was supposed to be in the palanquin.

I’ve heard a similar story from the great master of karate, Motobu Choki. There once was a man named Sakuma Chikudoun Peichin who, by all accounts, was a brave but imprudent fighter. Notwithstanding, Motobu raised his hat to this dauntless stalwart. Apparently Sakuma also liked drinking and often accepted challenges in exchange for awamori (a potent Okinawan liquor). Once in Shuri, Sakuma leaped into a miga (well) and then came flying out again. He was able to accomplish this feat by pressing his hands and feet against the sides of the well to support his powerful body. Even the powerful Motobu Choki was unable to perform such a magnificent feat.

Sakuma Peichins remarkable jumping technique was based on the skills of Makabe Chaan. Since boyhood Sakuma had heard of Makabe’s enormous size and great physical strength. Growing into a strong and powerful lad himself, Sakuma’s size rivaled that of his hero and role model, and, so too, did he try to develop his own skills in the image of the great Makabe Chaan. Because of Sakuma’s long arms and legs, and light but powerful body, he, like Makabe, was able to develop great leaping skills.

LAW AND ORDER IN THE CASTLE TOWN OF OLD SHURI

The Satsuma overlords maintained island tranquillity by force. This was accomplished by ensuring that local territorial administrators adhered to severe routine policies. Moreover, the Satsuma rearranged the class system in an effort to control the family lineages of the kemochi, and established an official department to record such information. However, together with the cumulative effects of feudalism, their efforts proved ineffective. It was during this time that King Shoko composed his satirical poem.

Poem:

Kamishimuya tsumete nakaya kuratatete

ubaitoru uchiyu usamigurisha

Shoko-O (King Shoko, 1787-1833)

Translation:

How poor and frugal both the upper and lower classes are now, in spite of a flourishing middle class. Ruling, during these unstable times, is so difficult.

Interpretation:

Kamishimuya refers to both the upper- and lower-classes of Okinawan people, while nakaya refers to the middle class. Composed by King Shoko, the poem aptly describes the dwindling condition of the kingdom, and his melancholy.

Responsible for the economic supervision of his own estate, Makabe Chaan was very familiar with the actual financial management of the upper class. It is said that because of Makabe’s shrewd business talent his family was able to survive and prosper, in spite of the government’s unstable financial circumstances. Yet, in the midst of a dwindling economy, Makabe Chaan was still known as the most outstanding bushi of his time. It is even said that the Satsuma bureaucrats recognized Makabe Chaan as Okinawa’s foremost bushi.

Although the old castle town of Shuri seemed to be a relatively peaceful place in which to travel, Satsuma magistrates often had stones hurled at them, and were sometimes attacked in the dark of night. Every time an incident of this nature occurred, the finger of blame was pointed towards men like Makabe. For even though he may not have been the actual culprit, Satsuma officials suspected that anyone brave enough to attempt such a thing must have been trained by someone like Makabe.

In spite of his innocence, Makabe was discouraged and told his family: “The purpose of bujutsu is not to compete with other people, but for training all aspects of oneself. I regret having competed with so many people in the past just to prove a point. As a man sows, so shall he also reap.” It is said that from that time forth, Makabe never took on another student.

According to his official resume, when Makabe was between forty and fifty years old he journeyed once to Fuzhou, China, and twice to Edo (the old name for Tokyo), on behalf of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It was expected that men like Makabe Chaan, “the scholar/warrior/diplomat,” would one day become powerful leaders for the Ryukyu government. However, Makabe Chaan passed away during the reign of Shoko-O, at the relatively young age of fifty-five years.

Shoko-O, the nineteenth century reclusive composer king, is perhaps better remembered for the artistic masterpieces he left behind than for his political ambivalence. Because of his reclusive preoccupation with music and poetry within the walls of the royal sanctuary, Shoko-O later became known as “Boochi-usuu,” the monk king.

Foreign ships appeared with increasing frequency in Okinawan waters during the reign of Shoko-O. Such sights indicated the beginning of the end of the Ryukyu Kingdom. The poem written by Shoko-O appears to reflect his anxiety over the turbulent changing social conditions of his time.

Since olden times in the Ryukyu Kingdom, Okinawans have adhered to the spiritual ritual of washing the bones of departed family members and airing out the O-hakka (family tomb) three and seven years after a death. In the case of Makabe Choken, we know that the date, October, 1829, indicating one of the dates his bones were washed, is inscribed on the vessel which contains his remains. Since the washing of bones is a custom performed three and seven years after one’s death, one might safely conclude that Makabe died in either 1823 or 1827. Living until the age of fifty-five, it is further reasoned that he was born in either 1769 or 1773. If these calculations are correct, then it would seem that Makabe lived about two centuries ago.

In 1772, during the ongoing Satsuma oppression, an enormous tsunami (tidal wave) hit Miyako and Yaeyama in the Ryukyu Archipelago, taking the lives of many people. Yet, in spite of this terrifying act of God, and the taxing circumstances under the iron hand of the Satsuma, the soul of the Ryukyu people never diminished.

It was during this period of great social adversity that the spirit of the Ryukyu bushi, now referred to as “karate spirit,” was profoundly embraced, further cultivated, and vigorously perpetuated. Surfacing as the most celebrated bushi of that burdensome era was “Tobitori” (the flying bird) Makabe Chaan, the first hero in the annals of Okinawan karate-do.